In my essays The Rule of the Octave in Major According to Fenaroli and The Rule of the Octave in Minor According to Fenaroli, I deal with the rule of the octave, a means of knowing which chord to play on each note of a major and minor scale in the bass, both ascending and descending, if the bass moves in rectilinearly stepwise motion.

The rule of the octave, however, doesn’t always apply. If the bass doesn’t move in rectilinearly stepwise motion, it may be necessary to play sonorities other than those suggested by the rule of octave, to play more ‘neutral’ sonorities. Two scale steps in particular are sensitive to this: ④ and ⑥.

In this essay, I will illustrate frequently used bass motions including ④ and ⑥ that are subject to not applying the rule of the octave (henceforth RO) to those scale steps. I will also show which chords can be played instead. In doing so, I draw and expand on the Metodo facile by Giovanni Furno (1748–1837), a source that contains useful guidance in this matter.

⑥

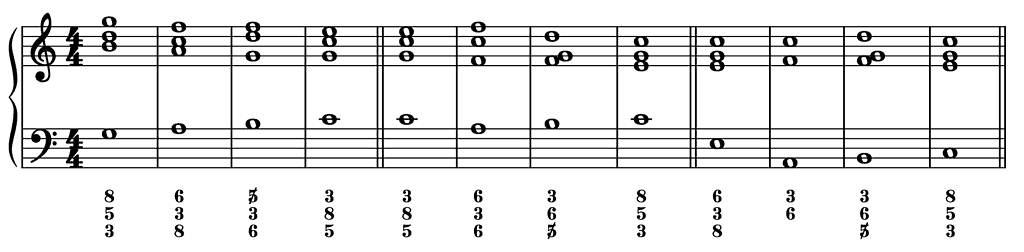

Let’s review first when the RO does usually apply regarding the chord choice on ⑥.

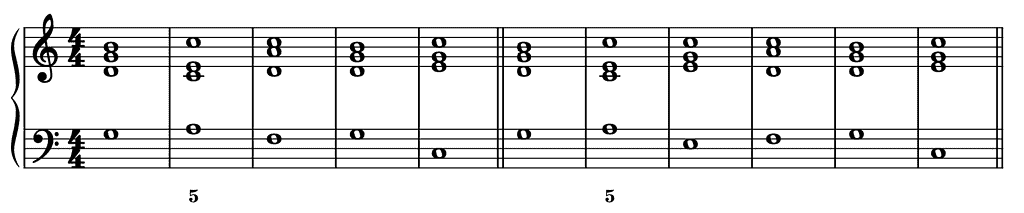

If ⑥ rises to ⑦, one will normally apply the ascending RO and play a sixth chord on ⑥. Yet the scale step that precedes ⑥ does not necessarily have to be ⑤ but can also be ① or ③ for instance.

And if ⑥ descends to ⑤, one will normally apply the descending RO and play a ♯6/4/3 or ♯6/3 chord on ⑥. Yet the scale step that precedes ⑥ does not necessarily have to be ⑦ but can also be ① or ③ for instance.

①–(⑦–)⑥–④/③/②

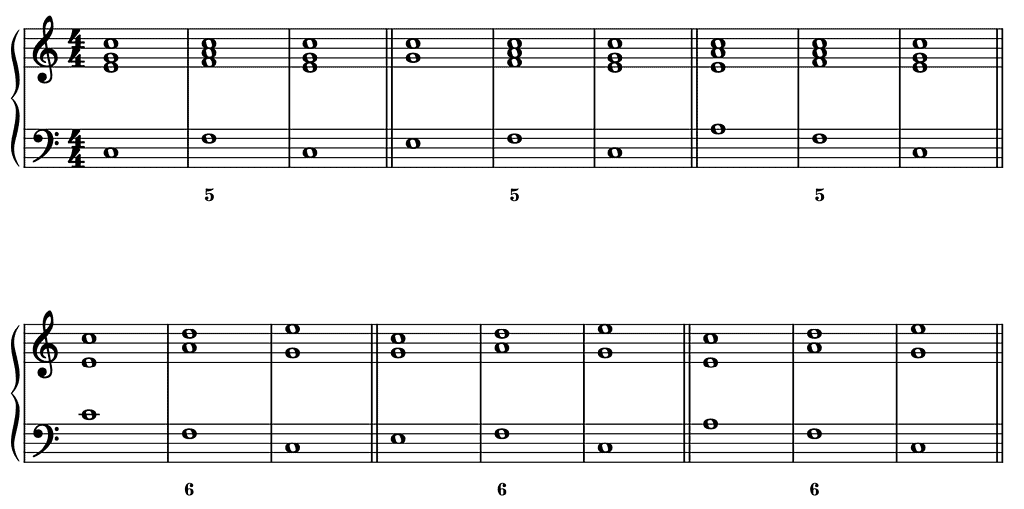

However, if ⑥ does not descend to ⑤ or rise to ⑦, but moves by leap to ④, ③ or ②, a ‘neutral’ chord is required. This is mostly a triad but can also be a sixth chord, which is actually the same chord of the ascending RO.

In the examples of the first system, ⑥ is both preceded and followed by a leap. Those examples open with a ①–⑥ snippet, which is followed by a descending leap. The examples of the second system answer for two notes to the RO. However, since the fourth note isn’t ⑤ but ③ or ②, the third note –⑥– can’t be set as a ♯6/4/3 or ♯6/3 chord. Instead, it requires to be set as a triad.

Do play a ♯6/4/3 or ♯6/3 chord on ⑥ in these examples and notice how it doesn’t work.

⑤–⑥–④/③

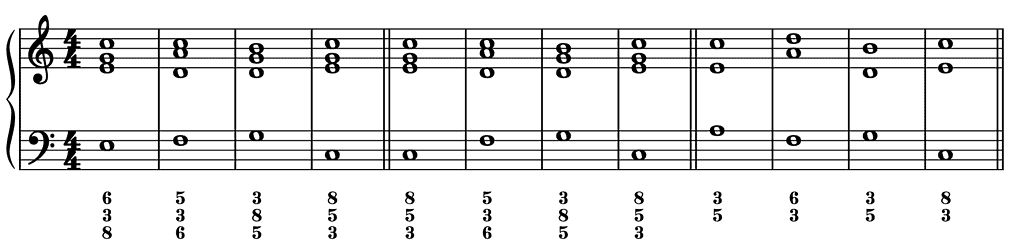

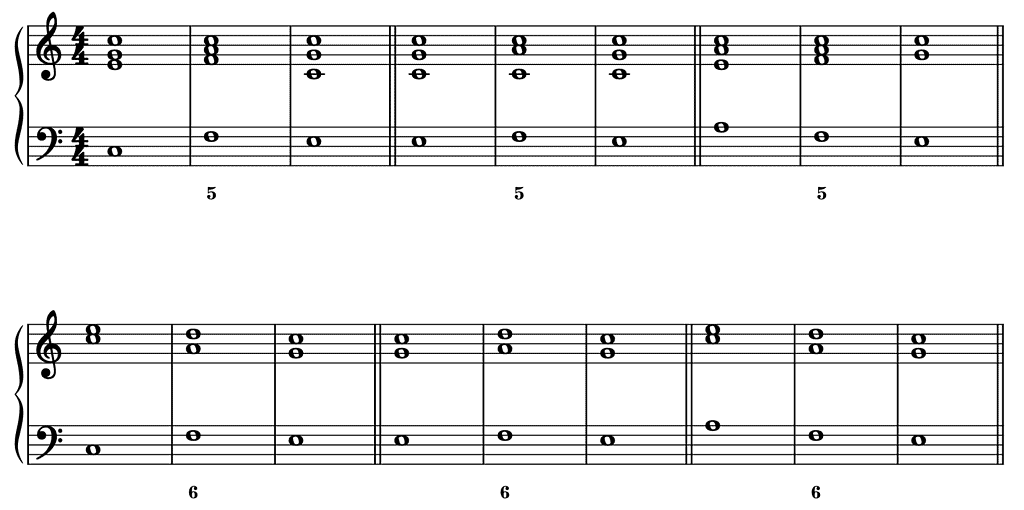

Another important deviation from the RO is when ⑥ is preceded by ⑤, both scales steps forming a broken cadence, and ⑥ is followed by a leap. In that case, ⑥ is mostly set as a triad.

When both ⑤ and ⑥ are set as triads, as is the case here, the voice leading requires due care and attention. Since there is no common note, the upper voices must move in contrary motion to the bass. Nevertheless, the voice that produces the leading note usually rises to the tonic. As a result, the third instead of the bass note of ⑥ is usually doubled in a four-part setting.

In fact, it could be argued that a triad on ⑥ is the more regular choice after a triad on ⑤ and that the ascending RO therefore contains an irregular sixth chord on ⑥. The reason to play a sixth chord instead of a triad on ⑥ in the context of the ascending RO is to smooth out the voice leading with the 6/5 chord on ⑦.

④

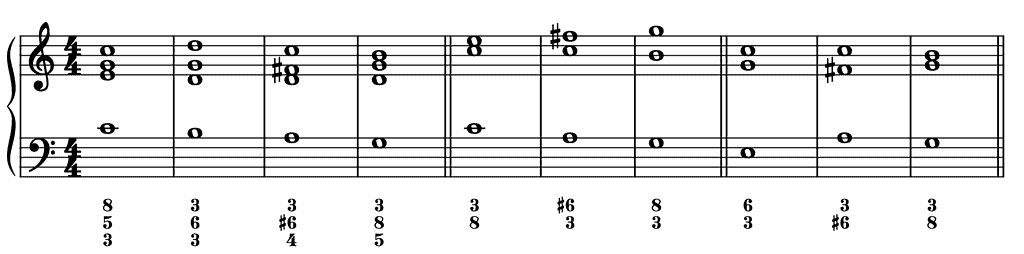

Let’s review now when the RO usually applies regarding the chord choice on ④.

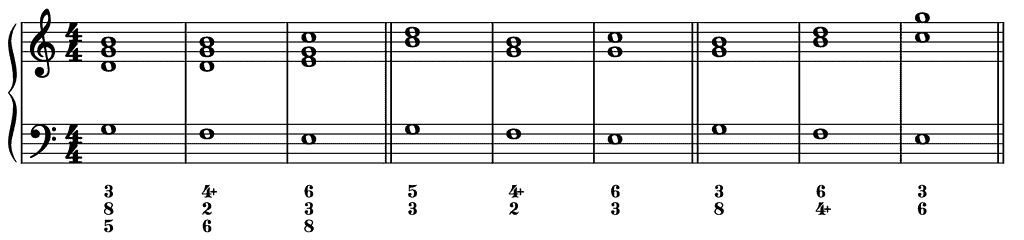

If ④ rises to ⑤, one will normally apply the ascending RO and play a 6/5 or a sixth chord on ④. Yet the scale step that precedes ④ does not necessarily have to be ③ but can also be ① or ⑥ for instance.

If ⑤ descends to ④ which in turn descends to ③, one will normally apply the descending RO and play a 6/4+/2, 4+/2 or 6/4+ chord on ④ (which are the same or highly similar sonorities as those played on ⑤):

Let’s see now when these sonorities are less likely.

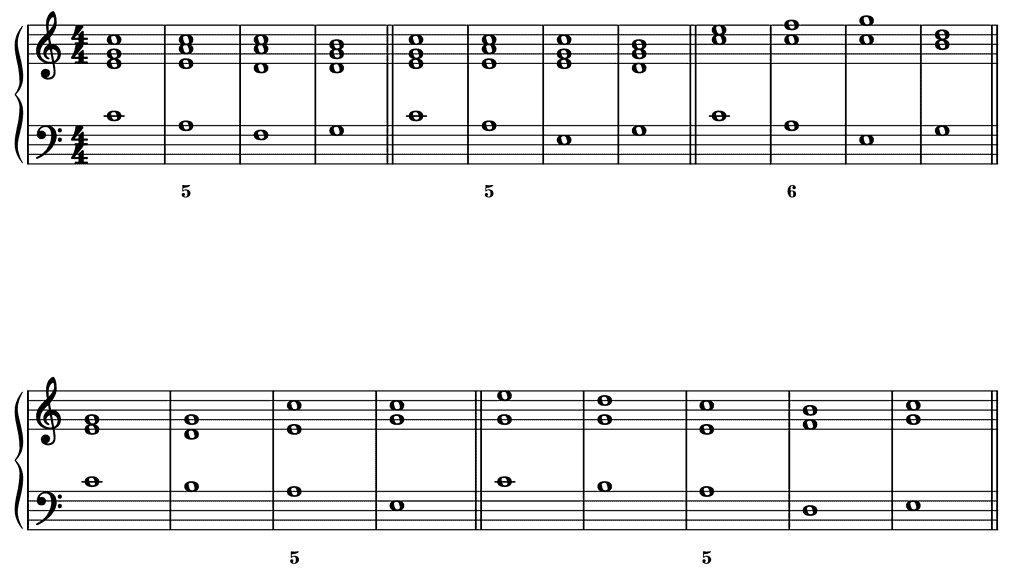

①/③/⑥–④–③

If the snippet ④–③ is not preceded by ⑤ but by ①, ③ or ⑥, it is more usual to play a triad on ④ than a 6/4+/2, 4+/2 or 6/4+ chord. A sixth chord is also a possibility, which in this case does not move to a triad on ⑤ but to a sixth chord on ③.

The snippet ④–③ with ④ set as a triad is often the start of a voice-leading pattern that Robert Gjerdingen has christened Prinner. (For more information see my series of essays on the Prinner, and more particularly my essay The Traditional Prinner.)

①/③/⑥–④–①

If ④ is followed by ①, ④ is usually set as a triad, although it can also be set as a sixth chord. When ④ is set as a sixth chord, it is usual that ➋ on ④ proceeds to ➌ on ①.

Further Reading (Selection)

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207–229.

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE, Preface and Editorial Principles by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. Partimenti Ossia Basso Numerato, Opera Completa Di Fedele Fenaroli. Per uso Degli alunni del Regal Conservatorio di Napoli (Paris: Imbimbo & Carli, 1813 or 1814).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Furno, Giovanni. Metodo facile breve e chiara ed essensiali regole per accompagnare Partimenti senza numeri (Naples, Orlando: n.d.)

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).