The best-known version of the rule of the octave is undoubtedly the one taught by Fedele Fenaroli and reinterpreted by Emmanuele Imbimbo, a version with a first-choice sonority for each scale step. (For more information on that type of rule of the octave see my essays The Rule of the Octave in Major According to Fenaroli and The Rule of the Octave in Minor According to Fenaroli.)

In this essay, I propose alternative settings for the rule of the octave. These settings are also based on one sonority/chord per bass note, but usually include temporary key shifts.

All alternative settings of the scales in this essay are derived from the counterpoint books by 18th-century Italian students. It goes without saying that this essay contains only a selection of possible alternative settings.

Ascending Alternatives in Major

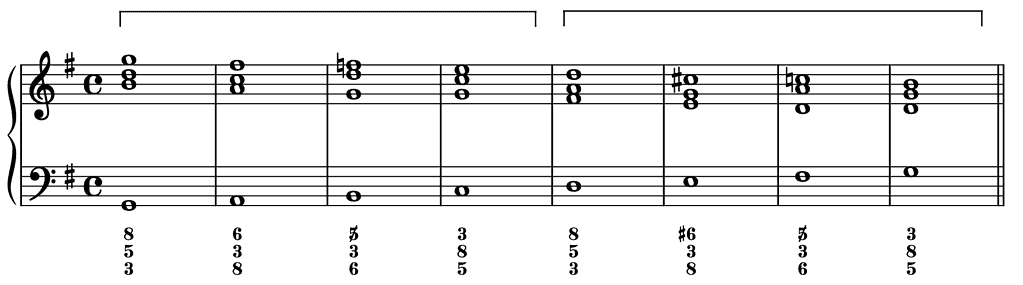

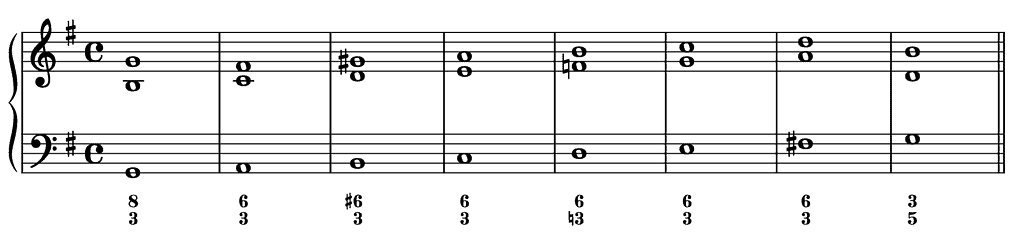

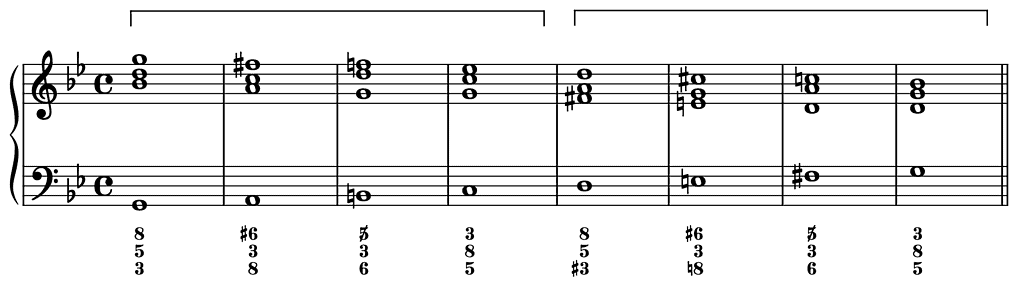

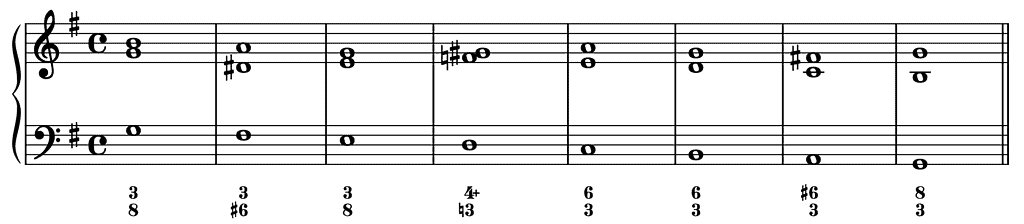

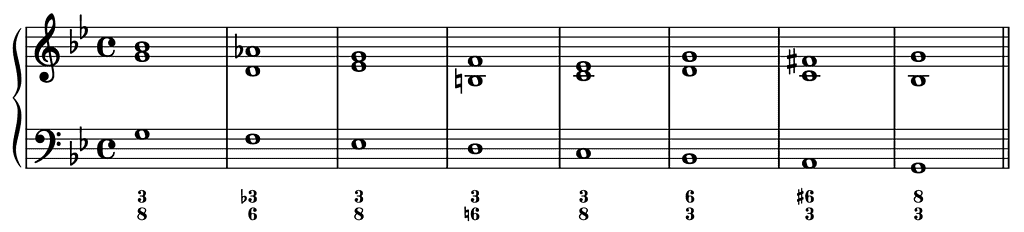

An ascending scale can be set so that the last four scale steps are an exact transposition of the first four:

In this case, the first resting point is not ⑤ but ④. This ④ functions as a local ① in C major, being the endpoint of a ⑦–① cadence or clausula cantizans in that key. This possibility stems from the fact that the snippet ③–④ is a minor second, which has the potential of becoming a local leading note and tonic, respectively. Observe the chromatic step down between stages 2 and 3 of the top voice of both tetrachords.

Giacomo Tritto (1733–1824), maestro at the Neapolitan conservatory La Pietà dei Turchini, published his two treatises —Partimenti e Regole generali and Scuola di contrappunto. In his Partimenti e Regole generali, he gives a setting that closely resembles this alternative setting:

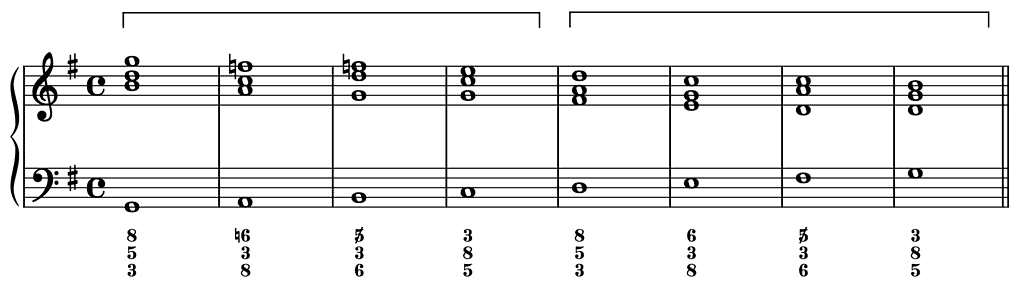

If we interpret the figures literally, the second tetrachord is not a literal transposition of the first. After all, Tritto asks for “6” on a, not “♯6”. While this version does work well as it is, it is tempting to assume that the sharp sign is lacking. Giorgio Sanguinetti, for instance, silently realizes the sixth chord on a with f♯, but still figures it with only “6” (Sanguinetti, 2012: 124). As a matter of fact, one could also interpret the setting of this scale in another way. Assuming that “(♮)6” on a is correct, one might wonder if a flat sign is not missing before “6” on d, implying b♭1 instead of b(♮)1. You find this version, transposed to G major, below.

That way, both tetrachords are also each other’s transposition. In fact, each tetrachord can be read/heard as the snippet ⑤–⑥–⑦–① of the standardized RO in C major and G major, respectively. The chromatic step down in the top voice is thus no longer present and is replaced by a repeated note one tone lower than the first melody note of each tetrachord.

The key of C major can be extended two more stages, returning to G major only at the very end of the scale:

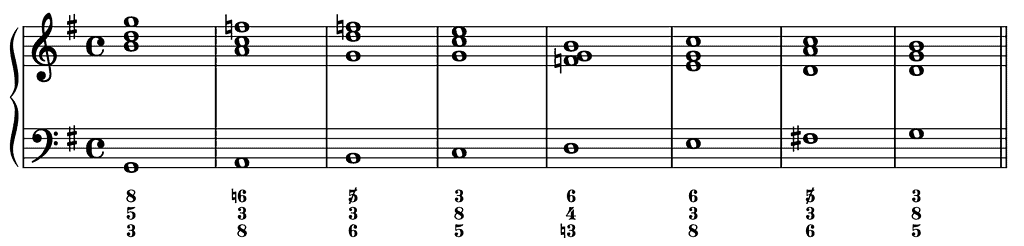

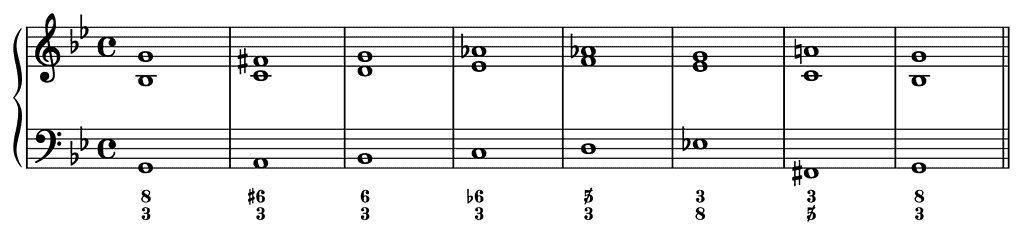

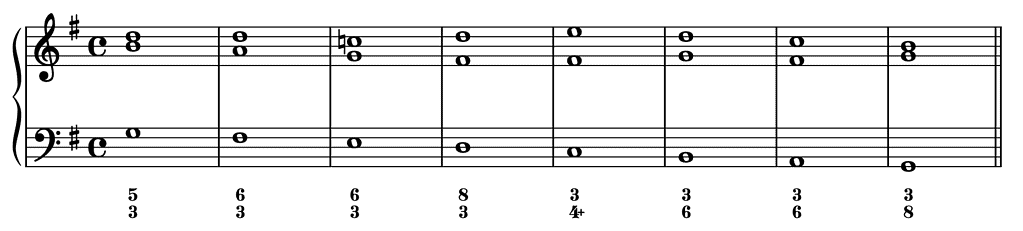

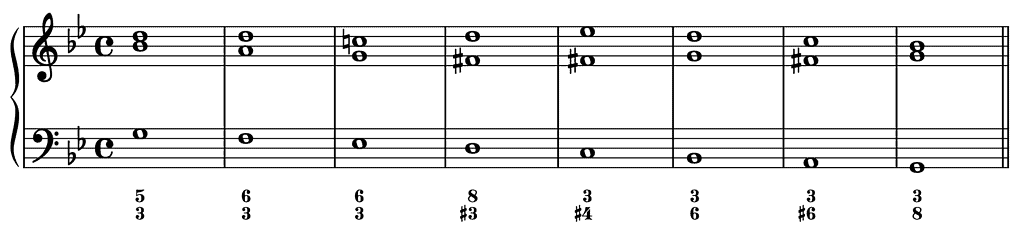

The next alternative setting of an ascending scale in major benefits from the potentially ambiguous character of the sixth chord on ②.

While the sixth on ② obviously functions as leading note in G major, it can also function as ➋ in E minor. That way, A–B–c is not set as ②–③–④ in G major but locally as ④–⑤–⑥ in E minor, the snippet ⑤–⑥ functioning as a broken cadence.

Since c is set as a triad and e as a sixth chord, one can set this snippet locally as ①–②–③ in C major. So, instead of setting d as a triad, as would have been the case in a regular setting of the RO, it is set here as a 6/4/♮3 chord.

This alternative setting thus starts and ends in G major, through E minor and C major.

Shouldn’t a Seventh be Prepared?

One may question, from the example above, if the seventh on B need not be prepared. According to Fenaroli, this is not mandatory, given the following argument: “The minor seventh and diminished fifth [and augmented fourth] are consonances because they do not require preparation, but only resolution by descending step.” (Fenaroli, Regole Musicali (ed. Domenico Sangiacomo), p. 6, footnote, my translation.) So, for Fenaroli, a chordal minor seventh was a consonance, not a dissonance. In a letter from 1791 to his student Marco Santucci, Fenaroli added an interesting nuance to the view of the minor seventh as a consonance, which renders it perhaps somewhat ‘less consonant’ than the normal consonances. He described the minor seventh as “a false consonance (una consonanza falsa), which needs to resolve” (letter quoted in Cafiero, La musica, p. 196, my translation; for more information on this matter see my article On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update (2018)).

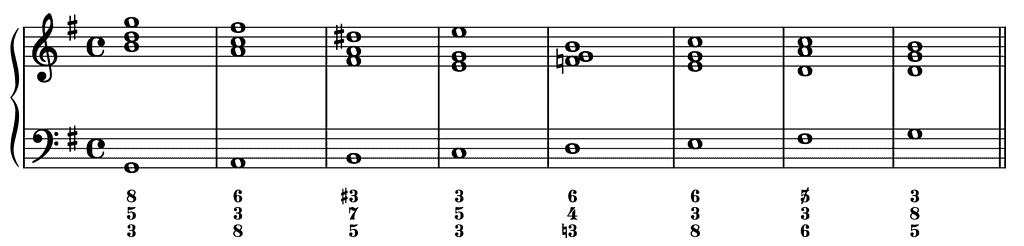

The following alternative setting is in three parts. It temporarily focusses on A minor during the snippet b–c (note the g♯1 instead of the g♮1) and on C major during the snippet d–e (note the f♮1 instead of the f♯1).

Note again the ambiguous character of a sixth chord with a minor third and a major sixth as the one on d. Following a ②–③ cadence in A minor, this sixth chord seems ideal for introducing a major triad on e with g♯1 in the top voice. (Do play this triad on e.) Instead, it rather functions as the first chord of a ②–③ cadence in C major.

Ascending Alternatives in Minor

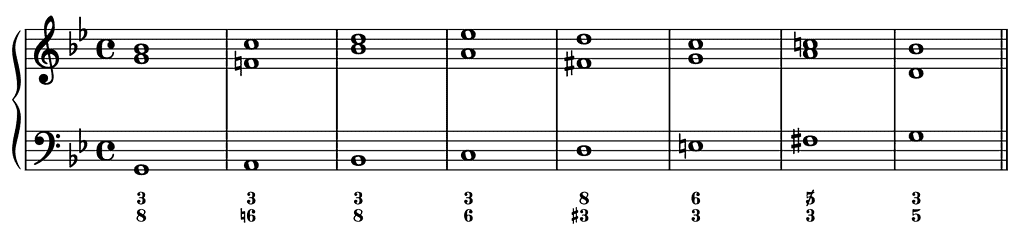

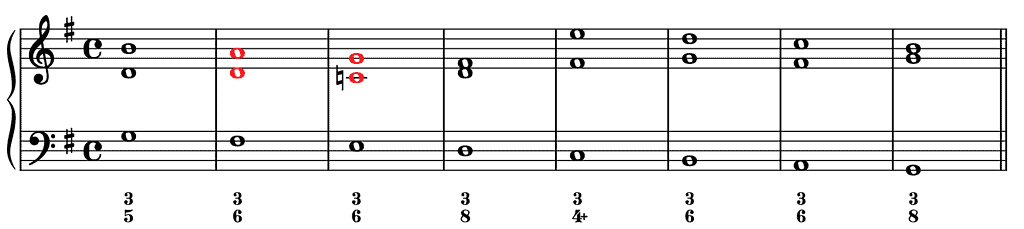

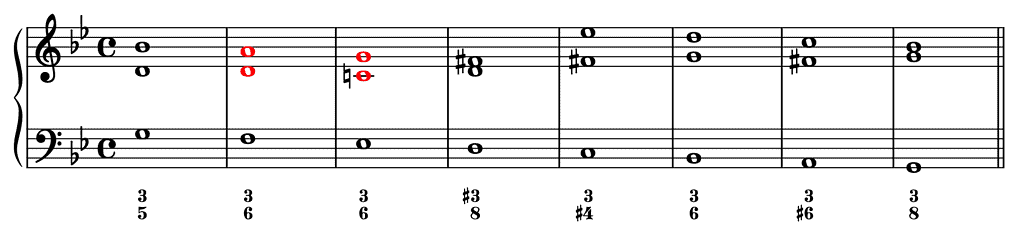

A much-used alternative chord in the ascending RO in minor is the Neapolitan sixth on ④:

Note the expressive melodic third a♭1–f♯1 in the top voice.

The same alternative chord can result in a temporary focus on E flat major. In this case, the bass has e♭ instead of e♮ during stage 6, after which it must leap down to the leading note via a melodic diminished seventh to avoid a melodic augmented second.

Since the snippet ②–③ is a minor second, it has the potential of functioning as a local leading note and tonic, respectively, as a ⑦–① in B flat major:

The key of B flat major can be extended two more stages, returning to G minor only at the end of the scale. This possibility stems from the potentially ambiguous nature of the sixth chord on ④, a chord that has its place in both G minor and B flat major.

The alternative setting with two tetrachords that are the exact transposition of each other and the chromatic step down between stages 2 and 3 of the top voice in each tetrachord works wonderfully well in minor too. For this alternative, however, ③ must be chromatically raised.

A second chromatic step down, which appears simultaneously with the one in the top voice, can be added to this version by transforming the 6/5 chord of stage 3 of the two tetrachords into a diminished seventh chord:

Descending Alternatives in Major

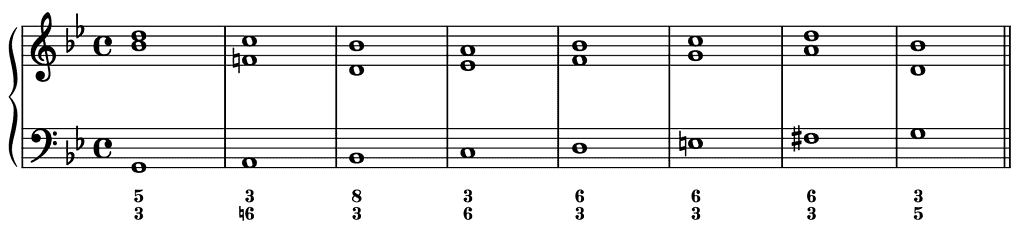

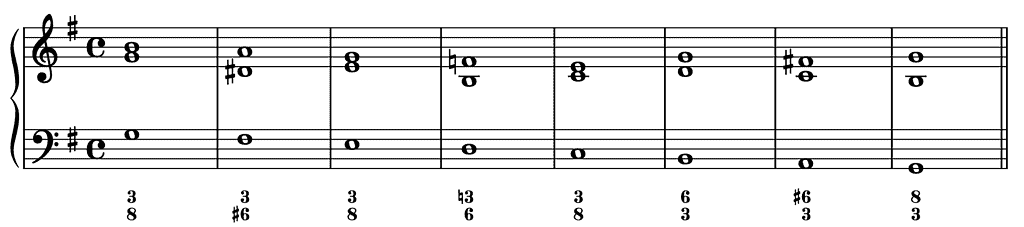

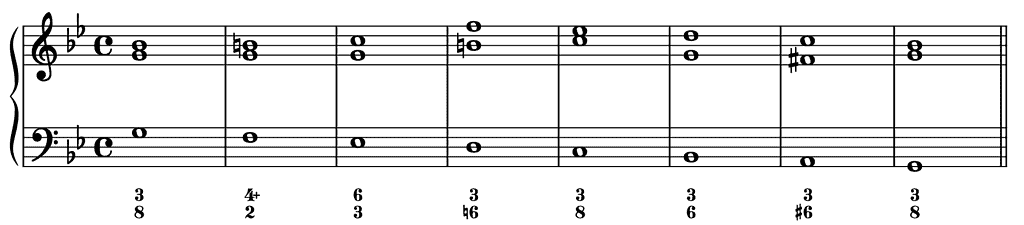

Instead of playing a major sixth on ⑥ (♯➍), one can also play a minor sixth ((♮)➍):

With this chord, there is no temporary focus on D major. Observe the alternative 4+/3 chord on ④ (see also my essay The Rule of the Octave in Three Parts).

However, one should pay attention to voice leading. After all, when the thirds are in the top voice during stages 2 and 3, this results in parallel fifths.

One can also interpret stages 2–3 and 4–5 as local ②–① cadences or clausulæ tenorizans in E minor and C major, respectively:

Keeping the clausula tenorizans in E minor during stages 2–3, one can also interpret stages 4–5 as a ④–③ cadence or clausula altizans in A minor:

One can obviously also play a 4+/2 chord —with e1– on d, but the f(♮)1 results in a better middle voice.

Descending Alternatives in Minor

Instead of playing an augmented sixth on ⑥, one can also play a major sixth:

Note the alternative 4+/3 chord on ④ (see also the paragraph Alternative Sonority on ④in my essay The Rule of the Octave in Minor According to Fenaroli).

It is important, however, that the sixth of the sixth chords on ⑦ and ⑥ are in the top voice. If the third is in the top voice, this results in parallel fifths:

The following alternative focuses on C minor during stages 2–5, the resting point being stage 5 instead of stage 4.

In the next alternative, stages 2–3 function as a ②–① cadence or clausula tenorizans in E flat major). Stages 4–5 transpose the tenorizans in E flat major to C minor.

Further Reading (Selection)

Cafiero, Rosa. “La musica è di nuova specie, si compone senza regole”: Fedele Fenaroli e la tradizione didattica napoletana fra Settecento e Ottocento, in: Il didatta e il compositore, ed. Gianfranco Miscia (Lucca: Libreria Musicale Italiana, 2011), p. 171–207.

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207–229.

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE, Preface and Editorial Principles by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. Partimenti Ossia Basso Numerato, Opera Completa Di Fedele Fenaroli. Per uso Degli alunni del Regal Conservatorio di Napoli (Paris: Imbimbo & Carli, 1813 or 1814).

Fenaroli, Fedele. Regole Musicali (Naples, Domenico Sangiacomo: 1795)

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).