The Prinner is a widely used schema in the 17th and 18th centuries and exists in many variants. In this essay, I will deal with the Traditional Prinner.

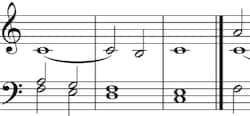

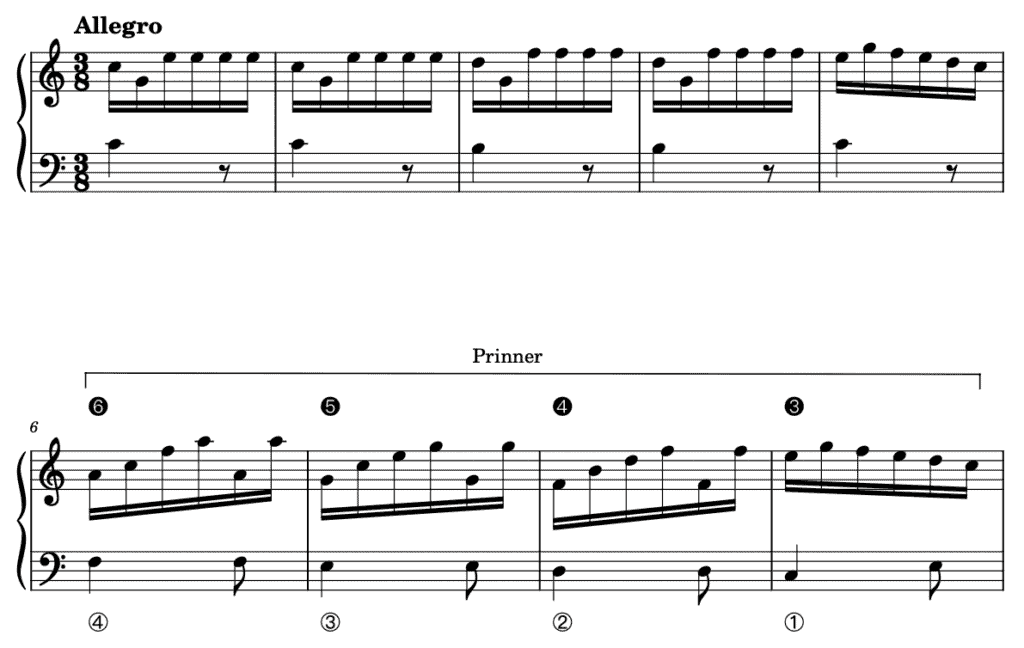

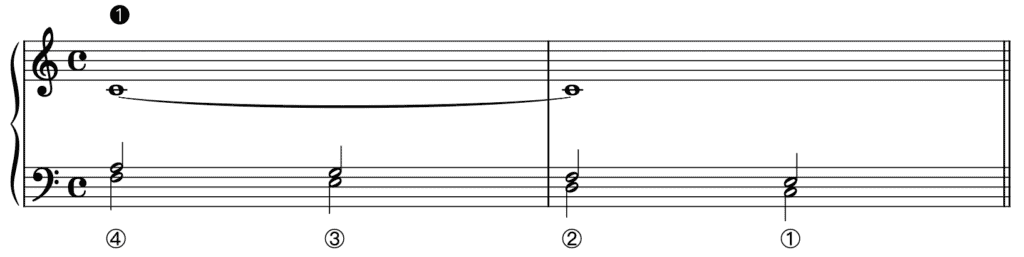

The Traditional Prinner is identified by a ④—③—②—① descent in the bass, a ➏—➎—➍—➌ descent in the upper voice (in parallel thirds with the bass) and, if in three parts, another upper voice that produces a ➊—➊—➊-➐—➊ melodic progression.

The Prinner is a term given by Robert O. Gjerdingen in his book Music in the Galant Style from 2007 in homage to the Austrian composer, organist and author Johann Jacob Prinner (1624–1694), who discusses this voice-leading pattern in his treatise Musicalischer Schlissl (Musical Key) from 1677. The Prinner was the galant risposta (answer) schema par excellence that allowed great compositional and improvisatory flexibility thanks to an important number of a variants and variations. In this article, I will elaborate on the oldest variant, which I have labelled the Traditional Prinner.

The Traditional Prinner is often used in a three-part texture and has the following characteristics:

- the bass steps down from ④ to ①

- one of the upper voices steps down from ➏ to ➌ (in parallel thirds with the bass)

- the other upper voice produces a stationary ➊ that becomes a vertical seventh above ② and resolves to ➐, forming a vertical sixth with the bass, before it rises to ➊ above ① (henceforth, the almost stationary line).

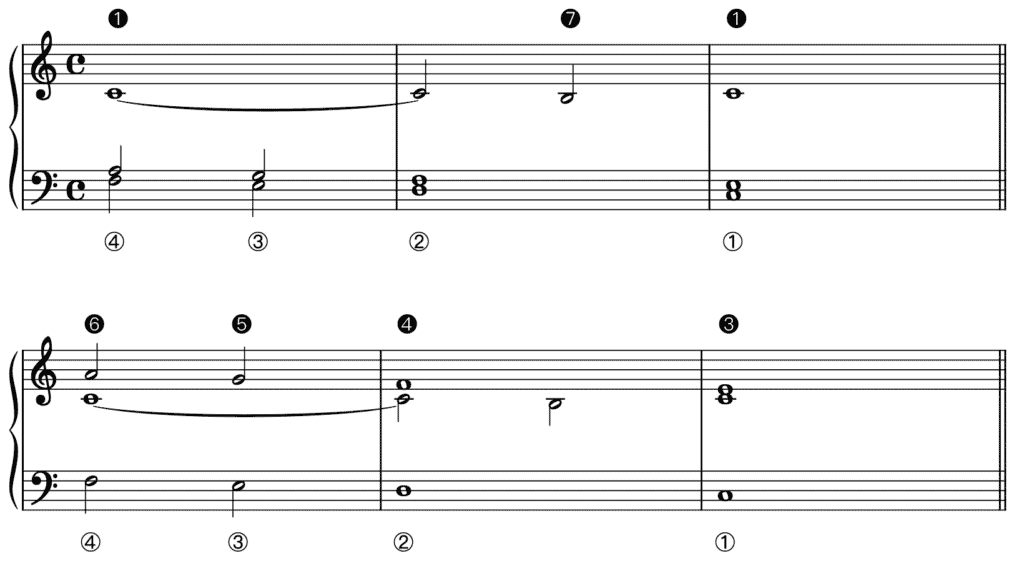

The Traditional Prinner, which functions as a mild ②–① cadence (or clausula tenorizans), appears in two versions:

- with the almost stationary line in the upper voice

- with the almost stationary line in the middle voice.

We can tentatively say that the first voice leading is perhaps somewhat more typical of the seventeenth century, while the second is more at the basis of 18th-century types of the Prinner, as I will elaborate in another essay. J.S. Bach, for example, uses the second version of the Traditional Prinner as the risposta schema in the allemande from his fifth French suite in G major BWV816:

(The Traditional Prinner starts on the downbeat of bar 2)

The High ➋ Drop

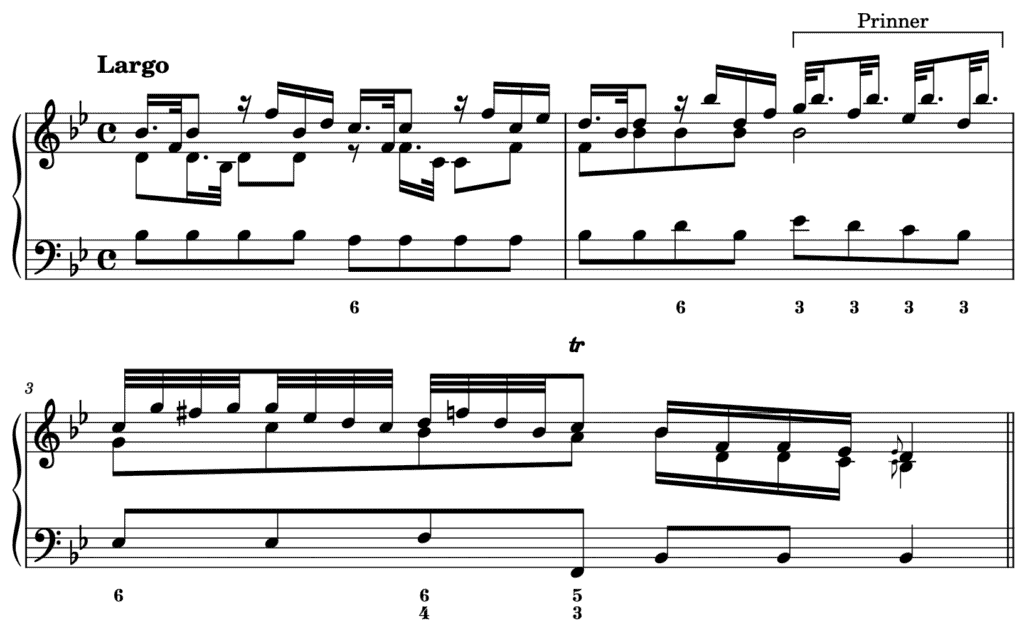

Notice the eighth sixteenth note in the soprano of bar 2 of the example above, the a2, ornamenting the ➍–➌ melodic snippet. Gjerdingen calls this gesture the High ➋ Drop “on account of its distinctive contour, served as a conventional sign of impending closure” and states that it is a regular ornamental feature of the Prinner (Gjerdingen, 2007: 74).

Number of Stages of a Prinner

Throughout this series on the Prinner, this schema is considered consisting of four stages, each of which coincides with one skeletal note of the ➏–➎–➍–➌ melodic progression and the ④–③–②–① bass line. In case of the Traditional Prinner, the third stage —including a 7–6 suspension— is often twice as long as stages 1 and 2.

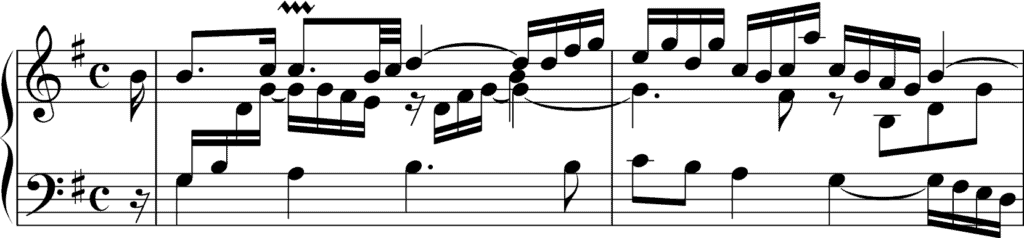

The Traditional Prinner Without 7–6 Suspension

One can also opt for a Traditional Prinner without a 7–6 suspension during stage 3. As such, this Prinner is dissonance-free and stage 3 is as long as any stage.

In the following example by Domenico Cimarosa (1749–1801), the opening gesture —called a Do-Re-Mi by Gjerdingen— is followed by such a Prinner. (I will deal with the Do-Re-Mi schema in a series of yet-to-published essays.) In this case, Cimarosa decided to put the ➏–➎–➍–➌ line in the top voice, as was customary in the 18th century. (Cimarosa was an Italian composer trained in Naples and one of the most celebrated composers of this time.)

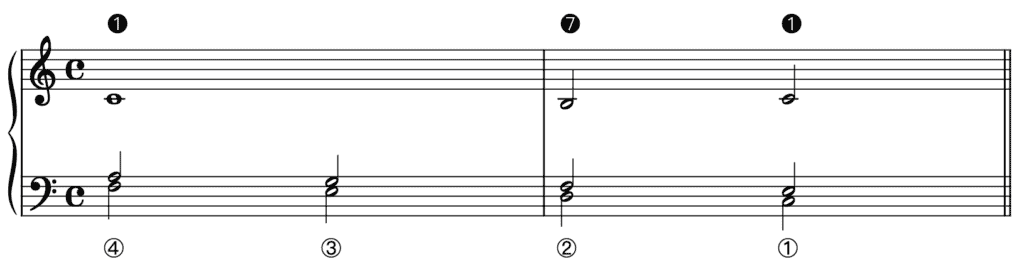

The Traditional Prinner With a Stationary Line Throughout

Occasionally, while the stationary ➊ does become a vertical seventh in relation to the bass at the start of stage 3 of the Prinner, it does not resolve to ➐, the stationary ➊ just remaining stationary throughout the Prinner. As such, stage 3 —again as long as any stage— works as a ‘passing stage’ including two passing notes.

This type of Prinner was used by Fedele Fenaroli (1730–1818) for instance in the Fac ut portem of his Stabat Mater in G minor:

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Prinner, Johann Jacob. Musicalischer Schlissl (1677).

Secondary Sources

Caplin, William E. Harmony and Cadence in Gjerdingen’s “Prinner”, in: What Is a Cadence? Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, ed. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015), 17–57.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).