Once the basic cadences (see my essay Cadences: The Basics), the rule of the octave (see my series of essays on this rule) and modulations were sufficiently trained, the partimento student embarked on the study of suspensions. He learned that suspensions could occur in the upper voices and in the bass, and that specific circumstances point at their presence.

In this essay I deal with suspensions in 1 or 2 upper voices. Basically, they are used if the plain chord would result in too slow a harmonic rhythm. There are 3 basic types of suspension in an upper voice: 4–3 and 9–8 for a triad, 7–6 for a sixth chord. Combining 4–3 and 9–8 is also an option.

At the end of this essay, I will already touch upon another technique to make the setting of a bass that lasts two instead of one beat interesting: postponing the dissonance. (I will elaborate on this technique in another essay.)

A Triad With a 4–3 Suspension

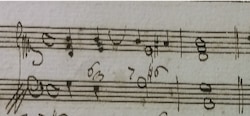

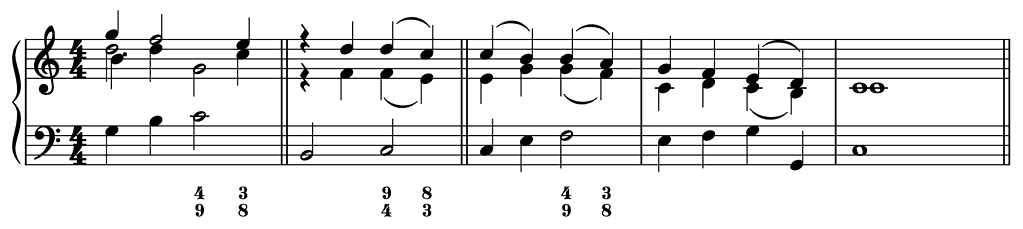

The concept of linking the use of dissonances/suspensions with harmonic rhythm was already introduced when the student learned the three basic cadences. The cadenza composta, for instance, is based on a ①–⑤–① bass progression in which ⑤ lasts two beats and ⑤ is set as a triad with a 4–3 suspension. In this case, the first beat of ⑤ is set with a dissonance of the fourth (➊), the second beat with the resolution, the third (➐). The following example shows a cadenza composta in major in first position, thus with the 4–3 suspension in the top voice:

Note how the on-beat dissonance is prepared by the c2 on the preceding weak beat, where it is a consonance (it simple doubles the bass note).

The technique of using a 4–3 suspension could be used for any bass note that is set as a triad and lasts two beats. Yet the most obvious bass note for this technique is ① since that scale step is the only one besides ⑤ that is also set as a triad in the rule of the octave.

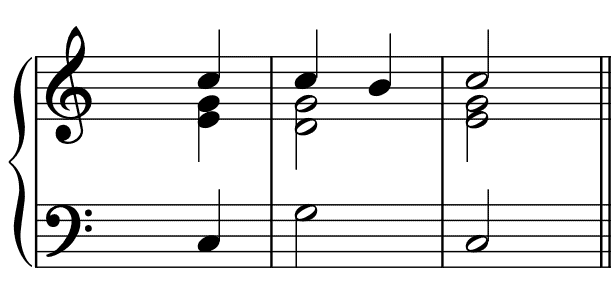

In the two excerpts of the following example, a half-note ① occurs in the first half of bar 2, lasts two beats and is set with a 4–3 suspension:

Note how the 4 of the 4–3 suspension is prepared with a seventh and diminished fifth, respectively.

While the resolution of the 4–3 suspensions in the example above occurs over the same bass note each time, the suspension can also resolve over a different bass note with a new chord:

A Triad With a 9–8 Suspension

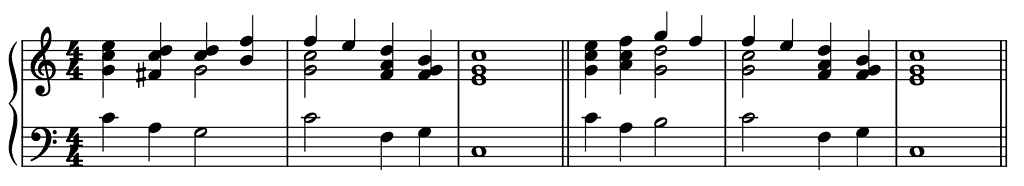

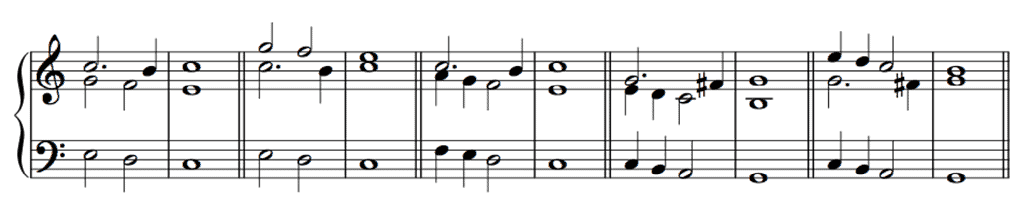

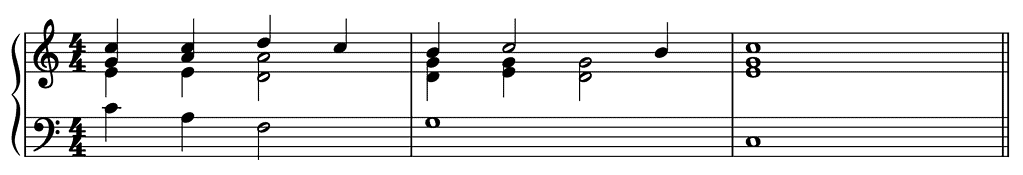

Another suspension that can be used to add a dissonance to a triad that lasts two beats is a 9–8 suspension. This type of suspension usually occurs on ①, ②, ④, ⑤ and ⑥. The example below shows 9–8 suspensions on ①, ④ and ⑤:

While the resolution of the 9–8 suspensions in the example above occurs over the same bass note each time, the suspension can also resolve over a different bass note with a new chord:

A Triad With a 9–8/4–3 Suspension

When a triad that lasts two beats is preceded by a (6/)5 chord set on a scale step a step lower, it can be set with a double, 9–8/4–3 suspension:

A Sixth Chord With a 7–6 Suspension

While there are several options to make a triad dissonant, there is basically only one option to make a sixth chord dissonant: the seventh temporarily replaces the sixth. (There are some other, more complex options, but these are beyond the scope of this essay.)

A 7–6 suspension often occurs on ② or ⑥ as part of a ②–① or a ⑥–⑤ cadence (clausula tenorizans), respectively:

In the third excerpt, the 7–6 suspension is part of a voice-leading pattern that could be used as a Prinner, in the fourth and fifth excerpts as a Modulating Prinner. (Note that I don’t simply label this voice-leading pattern a Prinner because it depends on where this pattern is used in a composition. After all, it only makes sense to call it a Prinner when it is used as a risposta schema. For more information on the Prinner and its structural use see my series of essays on this pattern).

A ⑥–⑤ cadence in minor occurs with both ➍ as ♯➍ as the resolution of the seventh, although the version with ♯➍ was more common in the partimento tradition:

In fact, if ➍ on ⑥ was used in 18th-century Italy, this was usually done to prepare the seventh on ⑤:

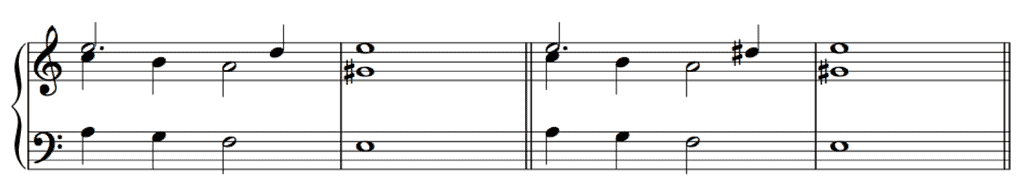

Consider now the next example:

Although the sevenths on beat 3 and 4 of bar 1 in each excerpt aren’t genuine suspensions but act as genuine chord notes of a seventh chord on ② and ⑤, respectively, I do want to include this version here to illustrate how a tenorizans is transformed into a basizans by simply transforming the half note in the bass in the second half of bar 1 of each excerpt into two quarter notes.

A 6/5 Chord With a 7–6 Suspension

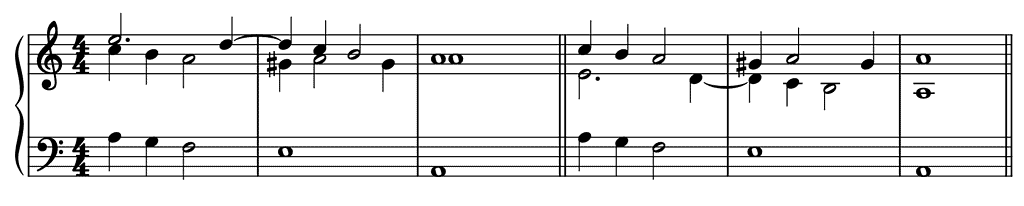

Until now, we saw only instances of consonant chords that are made dissonant. There is also the option to make chords that are already dissonant even more dissonant. Have a look at the next example:

Here, the 7–6 suspension offers an expressive and musically interesting solution for a …–④–⑤–… cadenza in which ④ lasts two beats and is set as a 6/5 chord. In this case, the sixth of the 6/5 chord on ④ is temporarily replaced with a seventh. (Explaining that the seventh on beat 3 of bar 1 acts as a suspension rather than as a chord factor of a genuine seventh chord is beyond the scope of this essay.)

Postponing the Dissonance

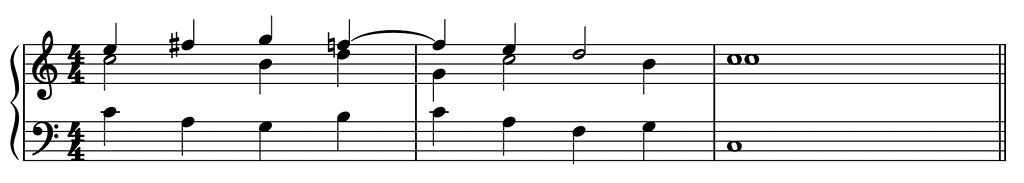

Another technique to deal with a 6/5 chord that lasts two beat is what I call ‘postponing the dissonance’. (This is somewhat off-topic —I will devote a separate essay to this technique and to what I call ‘horizontalizing the dissonance’— but it is too important not to touch upon here.) Consider the following example:

As is the case in the previous example, beat 4 of bar 1 holds a 6/5 chord on ④. Beat 3, however, is not dissonant but consonant, with a sixth chord.

Further Reading (Selection)

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207-229.

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).