The best-known version of the rule of the octave is undoubtedly the one taught by Fedele Fenaroli and reinterpreted by Emmanuele Imbimbo, a version that is based on a four-part realization. (For more information on that type of rule of the octave see my essays The Rule of the Octave in Major According to Fenaroli and The Rule of the Octave in Minor According to Fenaroli.)

The rule of the octave can also be realized in three parts. A common way of doing this is by setting scale steps 1 and 5 as triads and the other scale steps as sixth chords.

Since three-part voice leading switches frequently between the different positions of the RO, I only refer to positions when relevant.

Ascending RO

In my essay The Rule of the Octave in Major According to Fenaroli, I explain how the ascending RO can be divided into two main sections, sections that are musically also relevant: ①–②–③–④–⑤ and ⑤–⑥–⑦–①. An efficient, three-part realization is by setting the mobile/unstable scale steps (②, ③, ④, ⑥ and ⑦) as sixth chords. The stable scale steps (① and ⑤) are again set as (incomplete) triads. That way, both sections start and end with a stable triad, while all intervening scale steps are set as sixth chords.

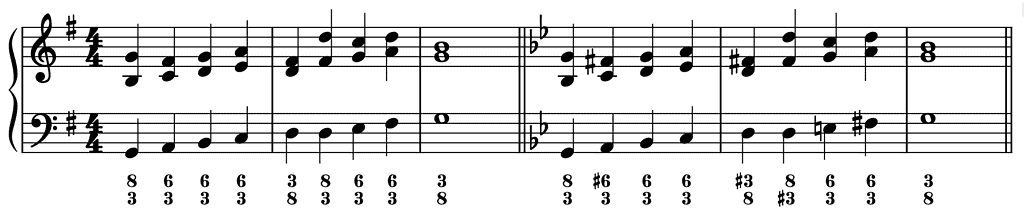

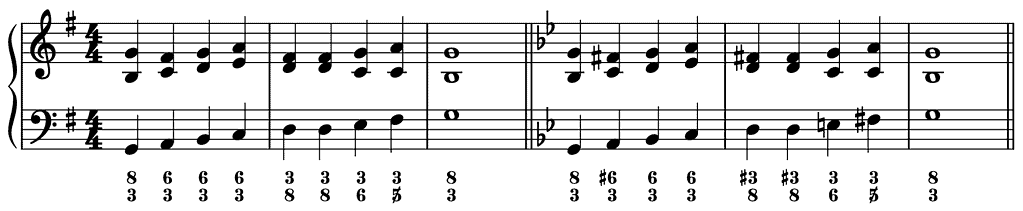

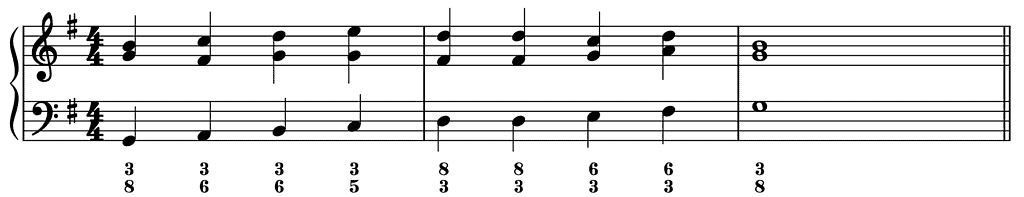

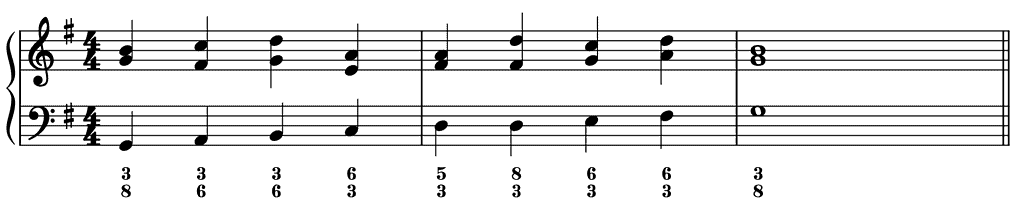

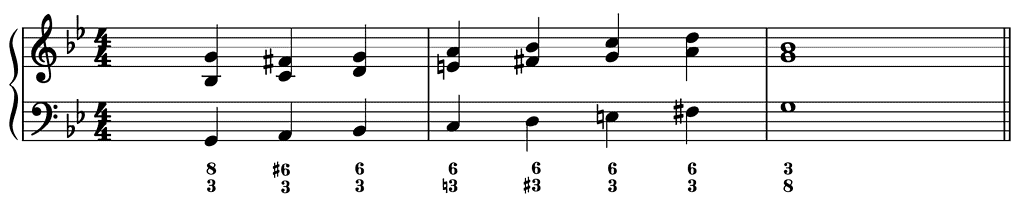

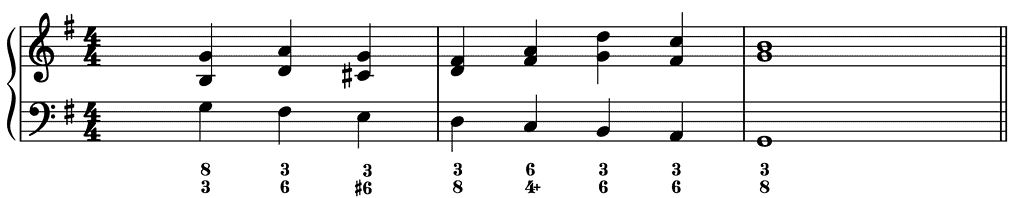

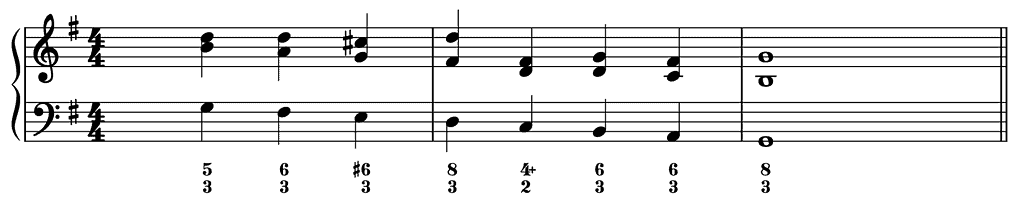

In the example below, I propose a three-part realization that is based on historical models. Note that

- this realization includes a repeated ⑤, which allows a change of position so that the sixths of the sixth chords on the unstable scale steps are always in the top voice

- the section from ① to ⑤ starts on ➊

- the section from the repeated ⑤ to ① starts on ➎.

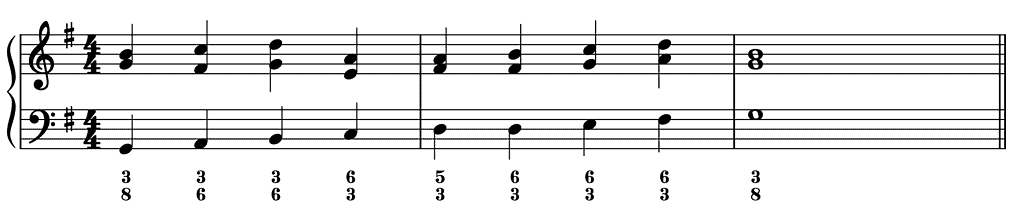

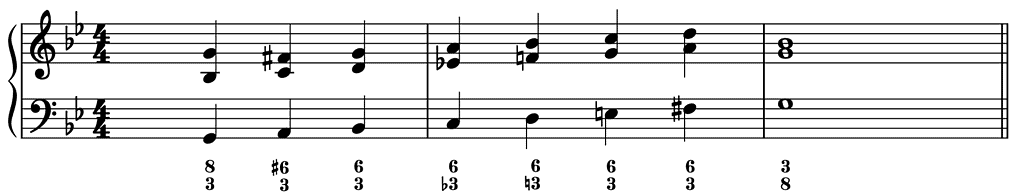

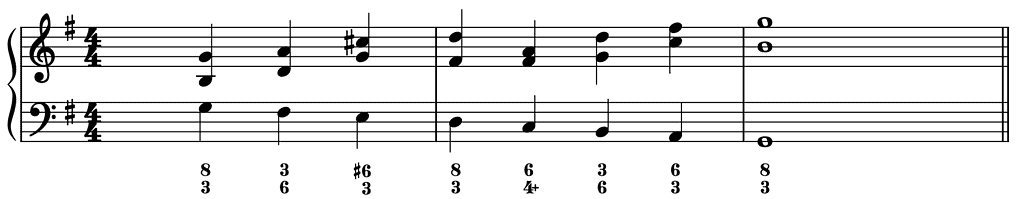

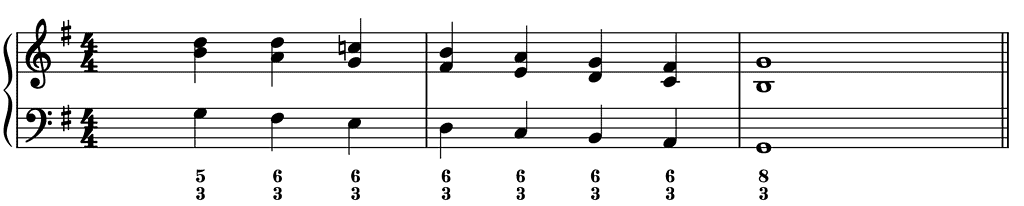

One can also opt to set ⑦ as a diminished triad instead of a sixth chord:

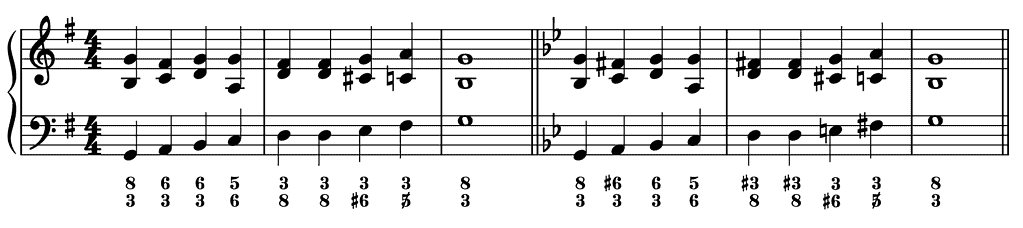

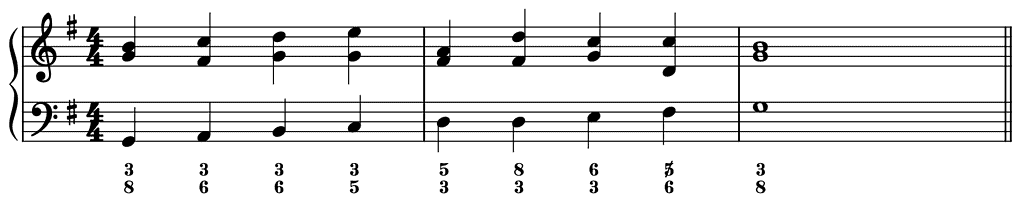

Instead of playing two repeated quarter notes c2 in the second half of the second bar, one can obviously play a half note or chromatically raise the first c2. In the example below, I have also changed the 6/3 chord on ④ into a 5/6 chord:

About Active Scale Steps

Note that active scale steps –leading notes, diminished fifths or sevenths– do not necessarily have to go to the expected note. If this this case, it is customary that the next note is also an active scale step. If the leading note doesn’t rise to the tonic, it regularly descends chromatically to become a seventh or diminished fifth, as in the example above.

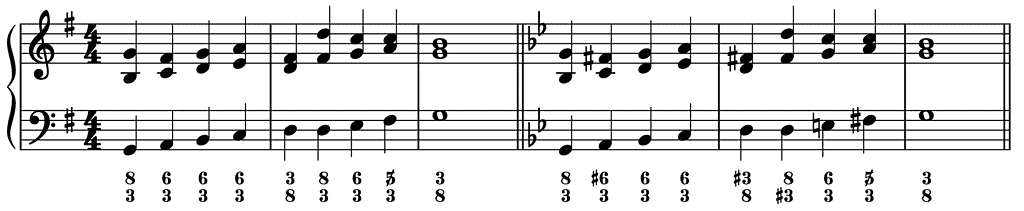

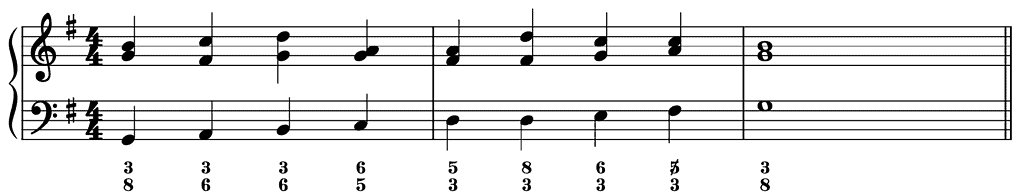

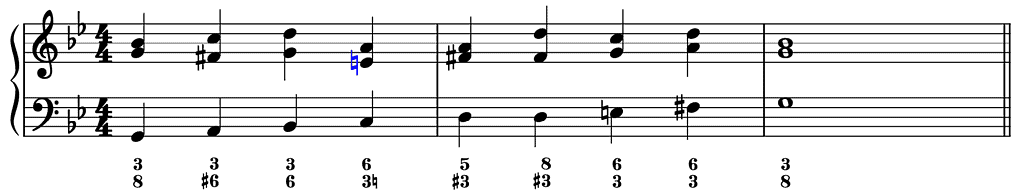

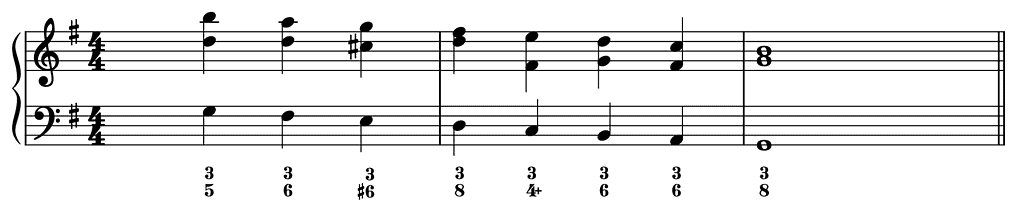

If one wants to stay in first position throughout, a diminished triad on ⑦ is a good solution to avoid voice-leading issues:

One can, of course, chromatically raise the sixth again on ⑥:

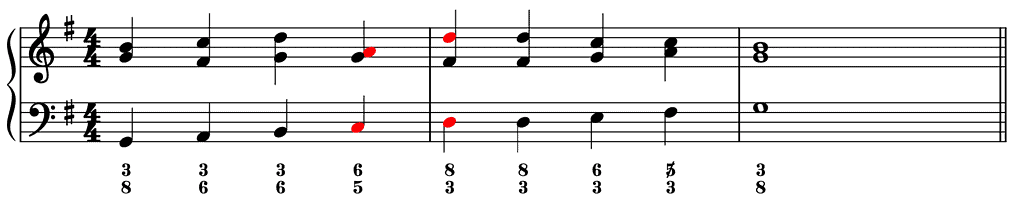

Playing a sixth chord on ⑥ and ⑦ would result in parallel fifths between the top and middle voices:

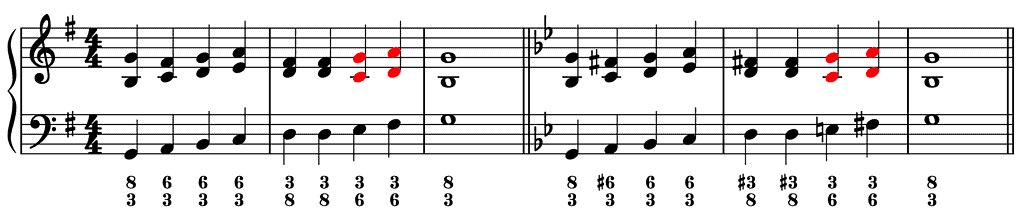

It is less common to play the first section of the three-part ascending RO with a voice leading in which the thirds of the parallel sixth chords appear in the upper voice. The reason for this is that one was trained to play parallel sixth chords with the sixths in the top voice, a voice leading that is easy and avoids pitfalls. When one does play the parallel sixth chords with the thirds in the top voice, the upper voices of these chords constitute fifths instead of fourths, resulting in potential voice-leading issues. While the succession of a diminished and a pure fifth was accepted in the 18th century (this voice leading occurs on the snippet ②–③ in major and minor), parallel pure fifths were prohibited (see the red notes in major). (The succession of a pure and a diminished fifth is blameless.)

There are several solutions for the parallel fifths on ③–④ in major. First, one can opt to play a triad instead of a sixth chord on ④, although this is not a first-choice sonority. After all, a triad on ④ is mostly followed by a sixth chord on ③ (the start of a voice-leading pattern that Gjerdingen calls a Prinner). (For more info on the Prinner see my series of essays on that voice-leading pattern and more particularly my essay https://essaysonmusic.com/the-traditional-prinner/.)

A beautiful melodic variant of this version arises when one plays a fifth instead of an octave on ⑤, a variant resulting in a descending melodic fifth over the barline:

Note that the sixth chord on ⑦ in the example above has been replaced by a 5/6 chord. Also note that the previous two examples also work in minor. In fact, from here on, I only give examples in major, which, however, can also be played in minor. If a specific remark is required in minor, I will do so.

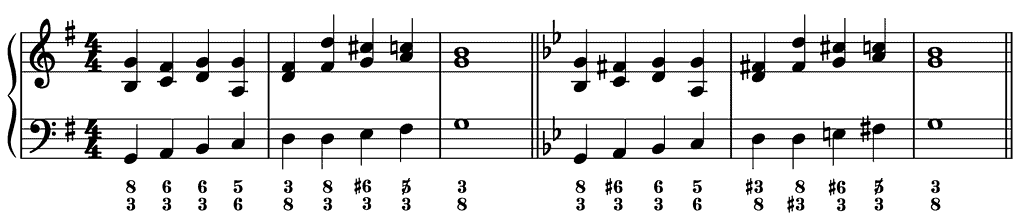

Secondly, one can play a 6/5 chord on ④, in which case the fifth on ⑤ in the top voice is no longer optional.

Otherwise, there would be a direct octave between the outer voices:

Note that the sixth chord on ⑦ in the two examples above has been replaced by another possible chord on that scale step, a diminished triad.

The 6/5 chord on ④ can be replaced by a 6/3 chord:

And this variation can in turn be varied by playing a sixth chord on the repeated ⑤:

In minor, pay attention to play a major third on ④ to avoid a melodic augmented second with the leading note:

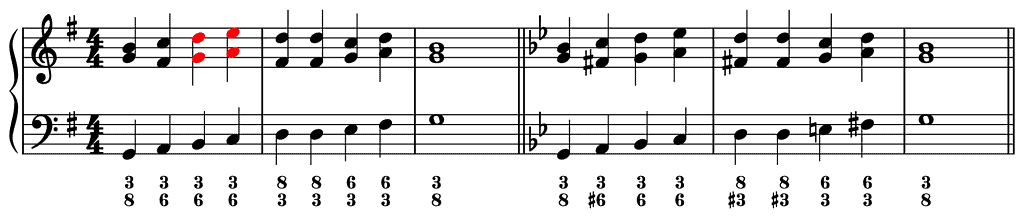

One can also realize the complete ascending scale with only sixth chords (apart from the triads on ①). In this case, there is no repeated ⑤.

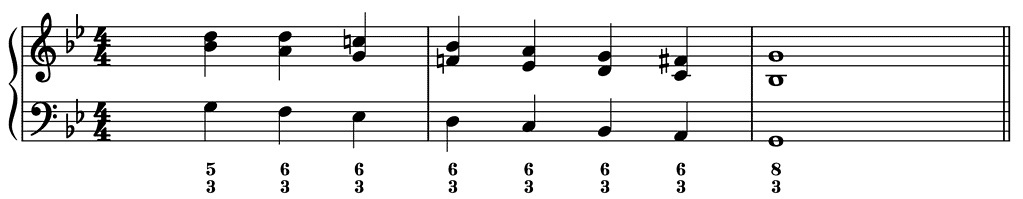

The three-part ascending RO with only sixth chords has two versions in minor. First, one can opt to stay entirely in the main key. To this end, one should play again a major third on ④ to avoid a melodic augmented second with the leading note:

Note the interesting sixth chord on ⑤ with a major third and a minor sixth.

Secondly, one can opt to touch briefly upon B flat major in the middle of the scale. Note the e♭1 and f(♮)1 on ④ and ⑤ respectively.

Descending RO

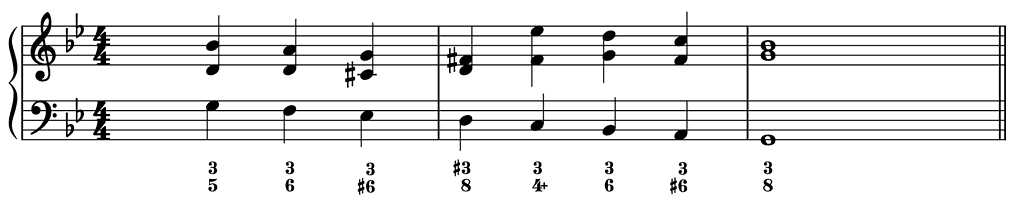

The descending RO can also be musically divided into two main sections: ①–⑦–⑥–⑤ and ⑤–④–③–②–①.

The section ①–⑦–⑥–⑤ has the potential, with regard to voice leading, of being played as a Modulating Prinner (for more information see my essay https://essaysonmusic.com/variants-of-the-prinner-part-1/). A typical feature of this voice-leading pattern are the parallel thirds in the upper voice.

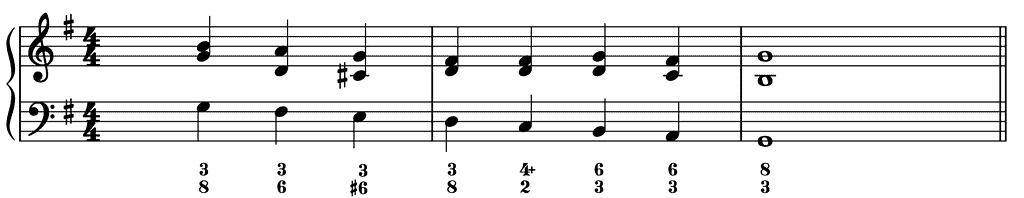

In the next example, the typical third voice of the Prinner is made explicit. A local ➊ during stages 1 and 2 (d1) is followed by a local leading note during stage 3 (c♯1) which in turn is followed by another local ➊ during stage 4 (d1).

The first section of the next example is identical to the previous one, apart from the fact that it starts on ➊ instead of ➌. As for the last three scale steps of the second section (⑦–⑥–⑤), they are a transposition of the last three scale steps of the first section (③–②–①): two consecutive sixth chords with the third in the upper voice followed by a triad with the third in the upper voice.

Note how, to ensure smooth voice leading, ④ is set with a 6/4+ instead of a 4+/2 chord.

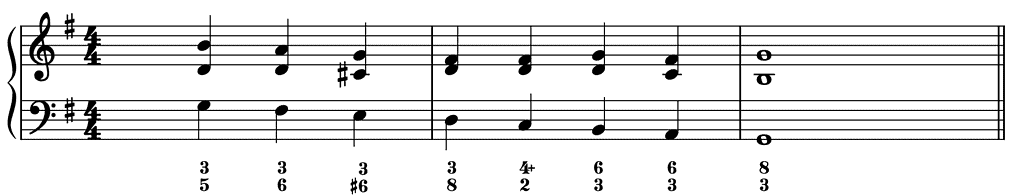

In the next example, the sixth chords on ⑦ and ③ have the third in the top voice, those on ⑥ and ② the sixth:

Note how, just as in the previous example, the snippet ⑦–⑥–⑤ is a transposition of the snippet ③–②–①.

One can also opt for an upper voice completely in parallel thirds with the bass. Note the 3/4+ chord on ④, which can be used in major only when the third occurs above the augmented fourth.

This voice leading is not an option in minor because of the melodic augmented second f♯2–e♭2 during the snippet ⑤–④. A solution for this voice-leading issue in minor is to play the realization of the first four stages an octave lower so that the melodic augmented second becomes a diminished seventh.

Note that the example above also works perfectly well in major.

The descending RO can also start on ➎ in the top voice:

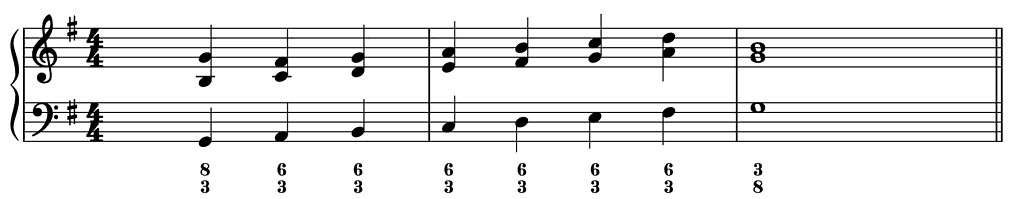

Just as is the case for the ascending scale, one can also realize the complete descending scale with only sixth chords (apart from the triads on ①).

In major and minor, a minor sixth c(♮)2 should be played on ⑥. In minor, a minor third should be played on ⑤.

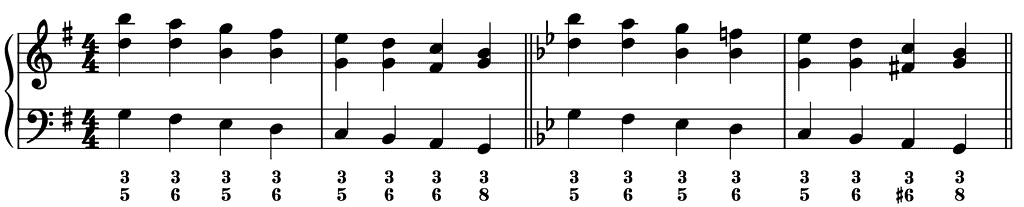

A descending scale can also be set with alternating triads and sixth chords, apart from the snippet ②–①, which is set with a sixth chord and a triad, respectively. That way, ⑤ is not perceived anymore as a first resting point within the scale, hence the altered metrical organization. Note how this setting in minor touches upon B flat major in the second segment.

This setting is also known today as a Stepwise Romanesca. For information see my essay https://essaysonmusic.com/the-stepwise-romanesca-the-basics/.

Further Reading (Selection)

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207–229.

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE, Preface and Editorial Principles by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. Partimenti Ossia Basso Numerato, Opera Completa Di Fedele Fenaroli. Per uso Degli alunni del Regal Conservatorio di Napoli (Paris: Imbimbo & Carli, 1813 or 1814).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).