In this essay, I will discuss a voice-leading pattern that is known today as the Stepwise Romanesca. This schema occurs not only in many Baroque and galant compositions but also in many pedagogical assignments from the 17th and 18th centuries. In partimento methodology, this schema offers an alternative setting for a descending scalar passage set according to the Rule of the Octave. In this essay, I will focus on the schema’s characteristics.

The Stepwise Romanesca is a descending sequential schema with 3 segments and 6 stages. Its basic features: a bass stepping down from ① to ③, a melody stepping down from ➌ to ➎ or alternately leaping up a third and down a fifth, each stage alternately set as a triad and a sixth chord.

This essay will deal with different settings of the Stepwise Romanesca in two- and in three-part textures. I will show how those textures can be realized with only consonances but also with the inclusion of suspensions (on-beat dissonances) in the bass. I will also show how certain chromatic alterations can result in temporary key shifts. Moreover, I will explain what a direct fifth is. And I will give tips on how to practise the material at hand.

The Leaping Romanesca Vs the Stepwise Romanesca

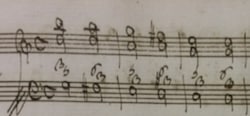

In my essay The Leaping Romanesca (The Pachelbel Pattern): The Basics, I deal with the Leaping Romanesca, aka the Pachelbel Bass or Pachelbel sequence.

The example above shows a three-part version of this pattern with the following first-choice characteristics:

- a bass alternating descending fourths and ascending seconds

- a melody descending in stepwise motion starting on ➌

- a middle voice descending in stepwise motion starting on ➊

- each stage set as a triad.

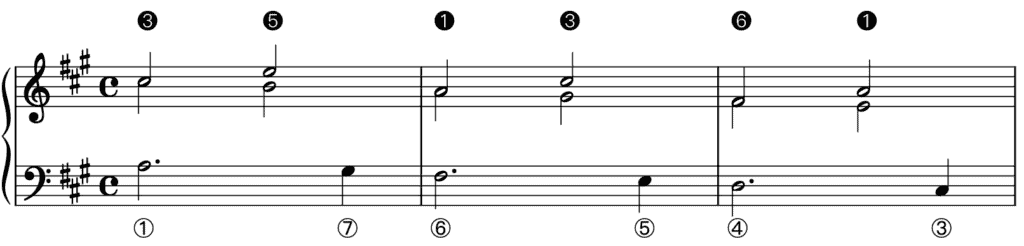

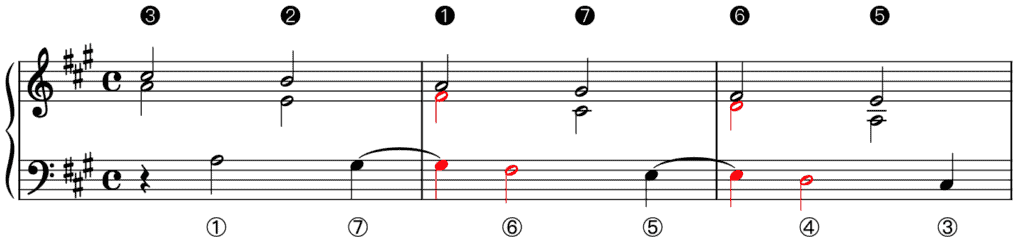

When one swaps the middle voice and the bass, a related pattern emerges:

Job IJzerman (in his book Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento — A New Method Inspired by Old Masters from 2018) and Robert O. Gjerdingen (in his book Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians from 2020), amongst others, call this pattern the Stepwise Romanesca.

The most important harmonic difference with the Leaping Romanesca, which consists only of triads, is the alternation of triads and sixth chords within the Stepwise Romanesca. This feature allows more easily to differentiate between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ beats: a triad has more weight than a sixth chord and is therefore better suited for ‘better’ beats. (The practical application of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ notes/beats was a major factor of at least 17th– and 18th-century performance practices. For more information on metre, see chapter 2 of my book Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue — Performance Practice Based on German Eighteenth-Century Theory (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2013). I will devote a series of yet-to-be-published essays on this topic as well.)

I will come back to the three-part version of this schema below. Let’s explore first some two-part versions.

The Stepwise Romanesca in Two Parts

Consonant Realizations

When we omit the middle part of the example just above, a version completely in parallel thirds emerges:

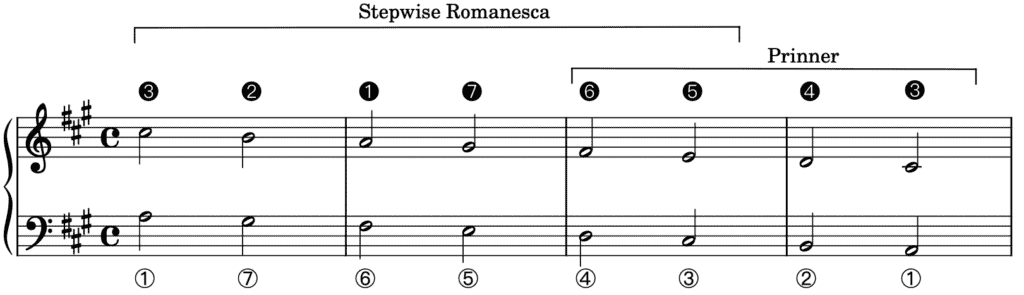

Note that the Stepwise Romanesca can easily be extended with one segment:

The example above nicely illustrates how the Stepwise Romanesca merges with another schema, a schema that Gjerdingen has baptized the Prinner. The two-part Prinner is characterized by a bass that descends in stepwise motion from ④ to ① and an upper voice that descends in stepwise motion from ➏ to ➌ in parallel thirds with the bass. I will explore the Prinner at length in a series of yet-to-be-published essays.

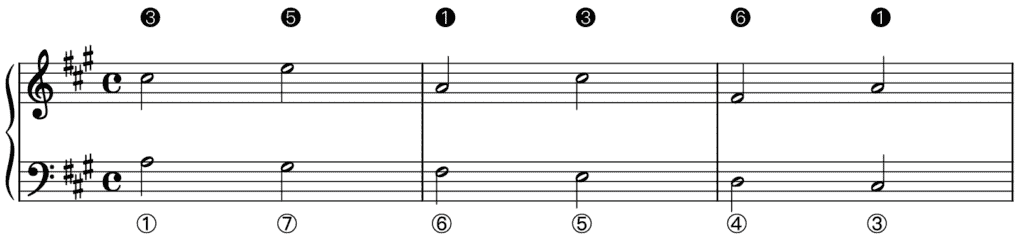

The Stepwise Romanesca can be set with another melody, a melody that starts on ➌ as well but alternates ascending thirds and descending fifths:

This setting results in the typical alternation of vertical thirds and sixths, which makes the two lines more individual. Another contrapuntal merit of this setting is the countermotion between both voices in each segment.

Realizations With Suspensions

Suspensions in (a two-part version of) a Stepwise Romanesca typically occur in the bass. (For more information on suspensions, see my essay The Leaping Romanesca (The Pachelbel Pattern): The Basics.)

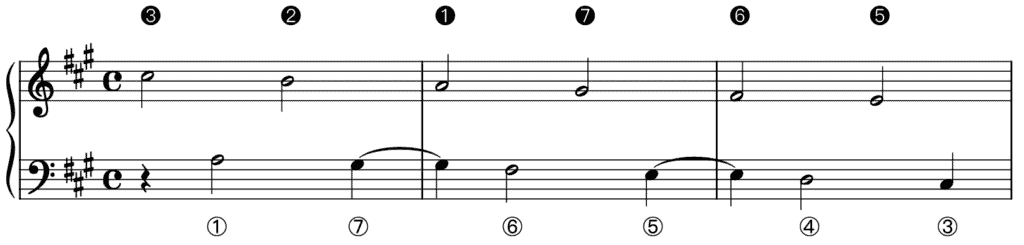

One can opt to include 2–3 suspensions in the bass only during the even stages:

One can also choose a 2–3 suspension chain in the bass:

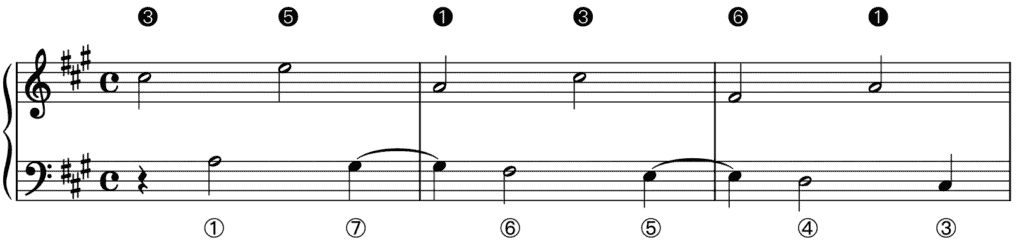

Note that you can also use the leaping melody as well as counterpoint to the syncopated bass:

In this two-part setting, however, the even stages tend to sound more like prolongations of the sonorities of the preceding uneven stages than dissonances with a suspension in the bass. After all, it is the presence of the vertical second in the middle of each bar that makes those moments into suspensions. (In three-part settings, the vertical fifth is usually combined with the vertical second in the other upper voice. As a result, the two sonorities in the middle of each bar are unequivocally dissonant —with a suspension in the bass— then consonant —the resolution of the suspension.)

The Stepwise Romanesca in Three Parts

Consonant Realizations

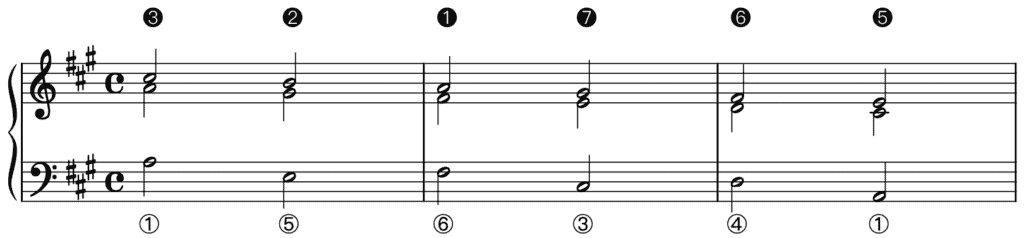

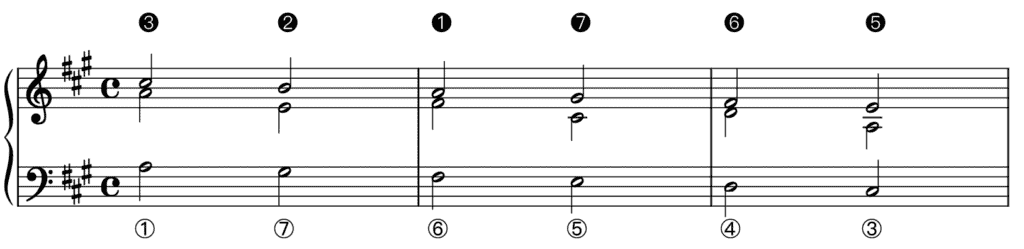

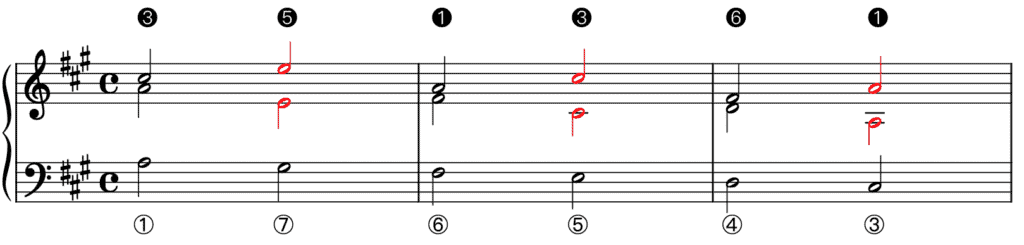

At the beginning of this essay, we saw an elementary three-part version of the Stepwise Romanesca obtained by swapping the middle voice and the bass of the Leaping Romanesca. Here it is once more:

In this version, the outer voices descend in stepwise motion, the bass from ① to ③, the upper voice from ➌ to ➎. As for the middle voice, it alternates descending fourths and ascending seconds, starting on ➊. As such, the (suggestion of) triads on the uneven stages are incomplete: the fifth is lacking and the bass note is doubled.

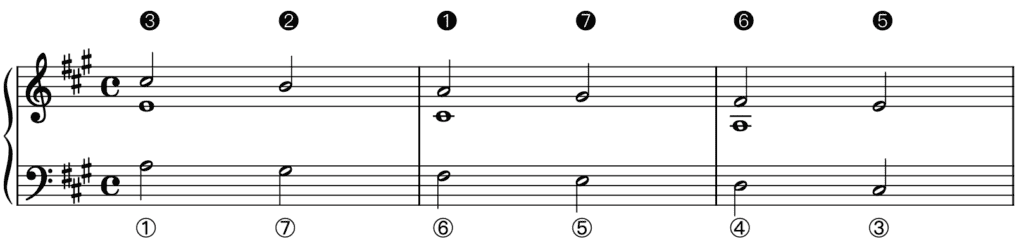

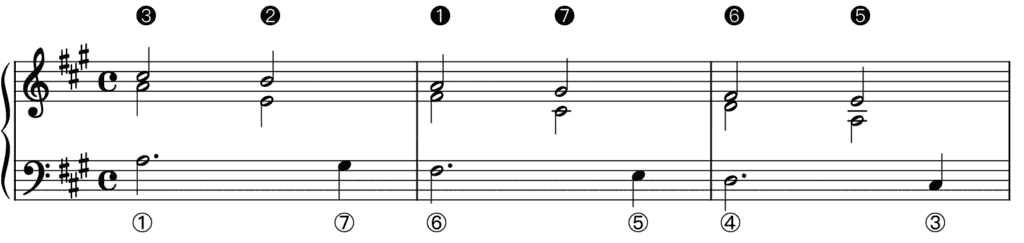

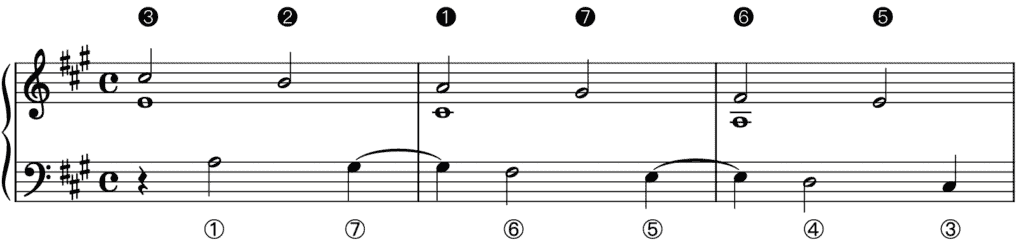

While this setting is perfectly fine, one can also opt for complete triads on the uneven stages. As a result, the middle voice becomes more static.

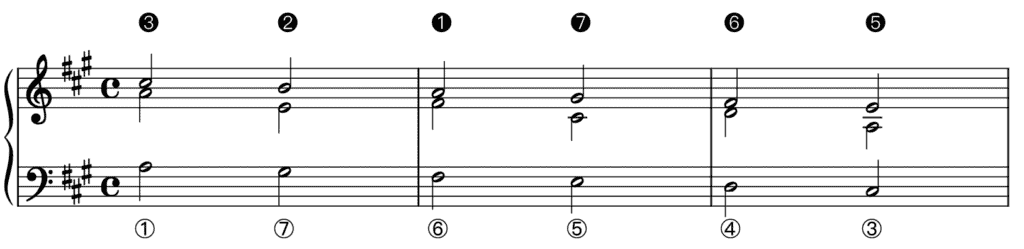

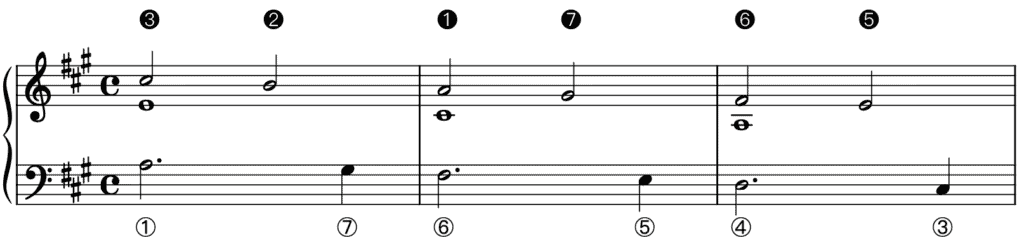

Swapping the middle and upper voices results in another usable setting:

Some might object to this version because of the direct fifths between the outer voices on the downbeat of the second and third bars. Still, if Mozart judges them to be correct, who will still dare to contradict him…? (Mozart uses this very voice leading in a passage from The Magic Flute KV620, when the Three Ladies sing “Drei Knäbchen, jung, schön, hold, und weise umschweben euch auf eurer Reise”.)

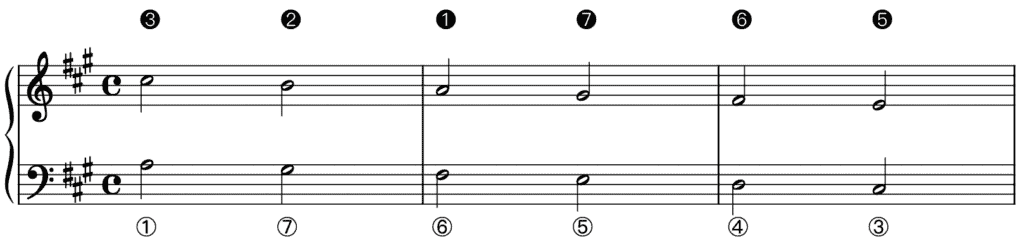

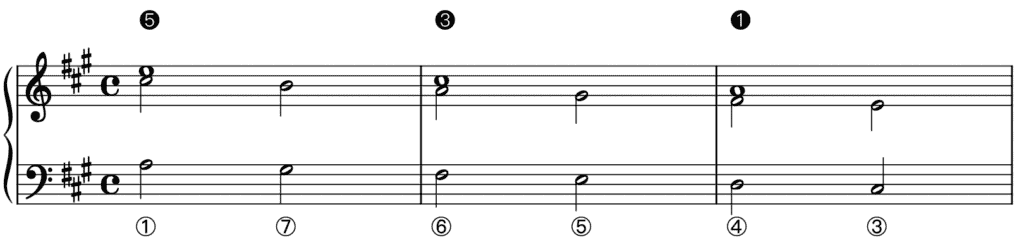

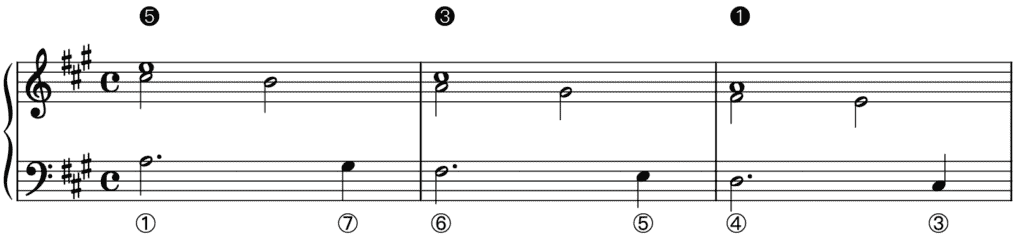

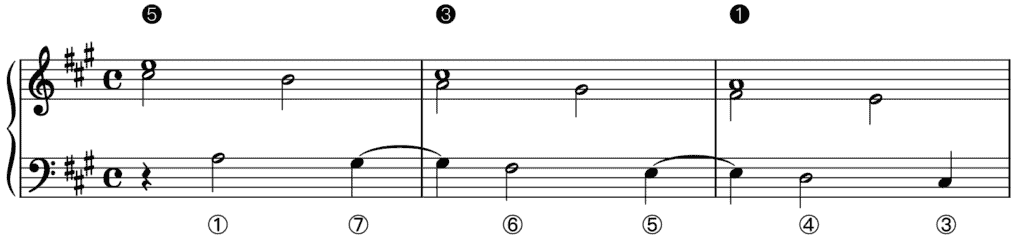

The two first-choice melodies of a two-part Stepwise Romanesca —a melody that descends in stepwise motion and a leaping melody— can sound simultaneously, creating a beautiful three-part version of the Stepwise Romanesca. In this case, the (suggested) triads on the uneven stages are again incomplete, with a doubled unison third.

Note that the following version with a leaping upper voice and a leaping middle voice would not have been quite acceptable by 18th-century standards. The reason for this is that the sixth chords are incomplete with a doubled vertical sixth (in red), a voice leading one rather avoided.

Realizations With Suspensions

Suspensions Only During the Even Stages

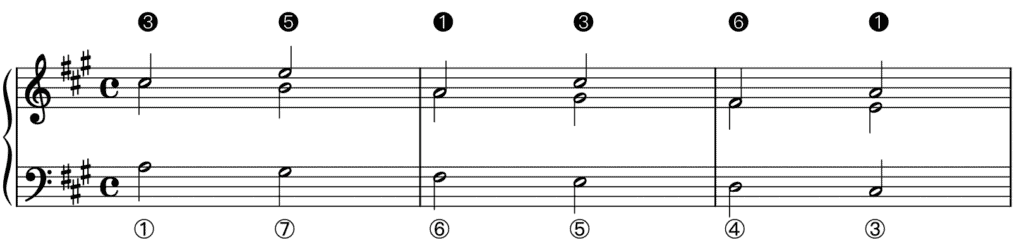

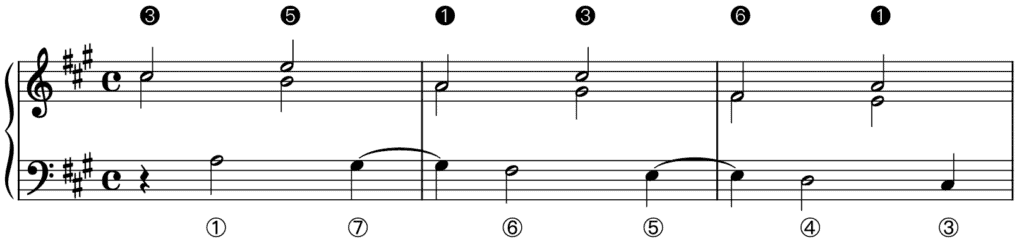

The following examples present three-part settings with suspensions in the bass only during the even stages:

Suspension Chain

The following examples transform the examples above into settings with a suspension chain in the bass:

Note that one setting from the section just above —the first one— has not been included and modified here. The reason for this is that the suspension in the bass on the downbeat of the second and third bars would create a seventh with the inner voice and resolve incorrectly to an octave on the second quarter of those bars. The example below illustrates this problematic voice leading on the uneven stages of the second and third segments (in red):

Temporary Key Changes

In my essay https://essaysonmusic.com/the-leaping-romanesca-two-part-embellishment-part-2/, I explain how the Leaping Romanesca can include local key changes.

The example above illustrates those key changes within the Leaping Romanesca triggered by the ‘red’ notes.

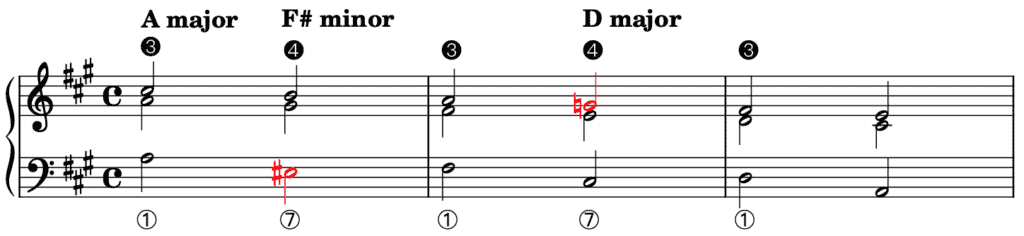

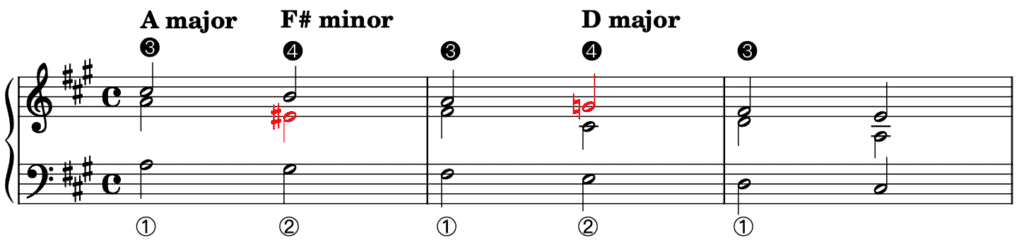

Since the Stepwise Romanesca is in essence the result of invertible counterpoint applied to the Leaping Romanesca, the same key changes can be applied to the Stepwise Romanesca.

In the example above, the second, third, fourth and fifth stages do not belong anymore to the key of A major. Stages 2 and 3 focus on F sharp minor, stages 4 and 5 on D major —note the modified, local indications of those stages in their respective keys. (Whether the last stage sounds again in A major or rather stays in D major depends on what follows.)

Because of the two ‘red’ notes in the example above, two local ②–① cadences emerge, the second of which is a third lower than the first. (The historical term for such a cadence is a clausula tenorizans. In his book Music in the Galant Style from 2007, Gjerdingen also labels this cadence a clausula vera.)

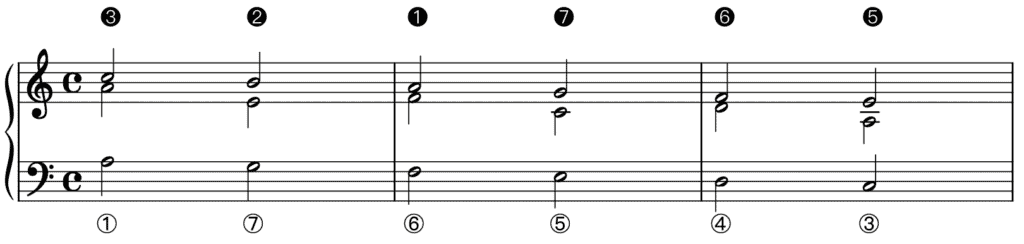

The Stepwise Romanesca in Minor

Although less common, the Stepwise Romanesca also occurs in minor, as does the Leaping Romanesca (see also my essay https://essaysonmusic.com/the-leaping-romanesca-the-pachelbel-pattern-the-basics/). In this case, the natural instead of raised ⑦/➐ and ⑥/➏ are used. Below I have included only one setting of the Stepwise Romanesca in minor, but you can easily modify the other settings in major we saw above to minor.

Tips for Practising

Before starting to practise the different realizations of the Stepwise Romanesca in two and three parts, it is a good idea to play only its bass and get acquainted with it, also from a keyboard-technical point of view. To this end, I suggest playing it first in C major and then in all major keys up to at least four accidentals. It is important to become familiar with somewhat less common keys such as E major and A flat major. Once you are comfortable playing the Stepwise Romanesca bass in a number of keys, you can start practising the various realizations. I would recommend starting with the two-part settings to maximize concentration on the (sole) upper voice. I suggest playing the two-part settings first in C major before passing on the keys with accidentals. Make sure that you are completely familiar with the two first-choice melodies: the one in parallel thirds with the bass and the leaping melody. After you have processed these settings, you can pass on to three-part settings, for which I suggest a similar approach. It is also worthwhile to practise all the two- and three-part variants of the Stepwise Romanesca in minor keys. Remember to use the natural ⑦/➐ and ⑥/➏ for those.

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. The Parma Manuscript — Partimento Realizations of Fedele Fenaroli (1809), ed. Ewald Demeyere (Visby: Wessmans Musikförlag,2021).

Secondary Sources

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).