This essay deals with possible interpretative differences between cut time (𝇍) and 2/2 in French Baroque music. To this goal I will explore several treatises from that period and area.

Cut time (𝇍) is different from 2/2 with respect to interpretation in at least three 18th-century French sources. In those sources, the differences between both metres concern tempo and whether the eighth notes should be played equally or unequally.

In this essay, I will quote from and comment on three important 18th-century French sources that make a distinction between the two metres at hand. Two of the three sources further illustrate that this was anything but a hard distinction and that other musicians were less precise in respecting a possible difference between both metres. For the readers who want to learn more on the French practice of inégalité, they might read the following two essays I wrote: https://essaysonmusic.com/what-is-inegalite-inequality-in-french-baroque-music/ and https://essaysonmusic.com/historical-terms-related-to-inegalite-inequality/.

Jacques-Martin Hotteterre le Romain

In his treatise L’Art de Préluder sur la Flûte Traversière from 1719, Jacques-Martin Hotteterre le Romain (1673–1763) explains that C barré (cut time) —𝇍— and 2[/2] are different metres that imply different rules regarding performance practice. (Hotteterre was a French composer and flutist, and was probably called the Roman because he stayed and worked in Rome from 1698 to 1700.) He explains first 𝇍, then 2[/2].

Mesure du C barré

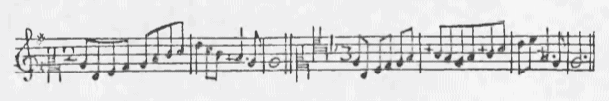

“This metre is indicated by the sign 𝇍. It is made up … of four quarter notes etc. Eighth notes must be equal in their regularity unless the composer has puts dots [after the uneven eighth notes]. Its usual mouvement is in four light or two slow beats. The Italians hardly use it and only for what they call Tempo di Gavotta, and Tempo di Capella, or Tempo alle breve. In the last, it is beaten in two light beats. … Mr. Lully used it in his operas rather indifferently with that of the simple 2. One finds there much inégalité as well as in several others. It seems to me quite correct in the Tempo di Gavotta of the Italians, and in the two following examples. … One can conclude that this metre occupies the middle between the four beats marked with a C and the two beats marked with a simple 2, as we are going to see.”

public domain, available on https://imslp.org;

modified translation from Boyer, L’Art de Préluder — A Translation, p. 173–174

To summarize Hotteterre’s directives for performing 𝇍, this metre can be rather fast with four light beats or slow with two (slow) beats. (Compared to the modern view of this metre with two half-note beats per bar, it is interesting to observe that Hotteterre describes 𝇍 first as a metre with four quarter-note beats per bar.) Whatever metric organization one opts for, 𝇍 seems to be slower than 2[/2]. The eighth notes are equal, unless the composer writes dotted rhythms, as his example by Louis-Nicolas Clérambault (1676–1749) illustrates. (Clérambault was a French composer and organist.)

Mesure a 2 temps

“This metre is marked with a simple 2. It is made up of two half notes or the equivalent; it is beaten in two equal beats. It is usually lively and piquée (articulated and characterful). One uses it in the beginning of opera overtures, in Entrées de Ballet, marches, bour[r]ées, gavottes, rigaudons, branles, cotillons etc. The eighth notes are pointées (unequal). It is unknown in Italian music. … If one uses it for slow pieces, one should give a notice. In addition, one can say that this metre is properly that of C divided in two, and with the eighth notes changed into quarter notes.”

public domain, available on https://imslp.org;

modified translation from Boyer, L’Art de Préluder — A Translation, p. 175–176

To summarize Hotteterre’s directives for performing 2, it is usually fast, lively and what he describes as piquée. The latter term for Hotteterre seems to refer to an articulated and vigorous, characterful way of performing. (For more information on this problematic term, see my essay https://essaysonmusic.com/historical-terms-related-to-inegalite-inequality/.) Contrary to 𝇍, where the eighth notes should be played equally, the eighth notes in the simple 2 must be played unequally. (Hotteterre defines the term pointer as “to play unequally”. Other 18th-century French writers, however, define it in other ways. For more information on this equally problematic term, see again my essay https://essaysonmusic.com/historical-terms-related-to-inegalite-inequality/.)

Michel Pignolet de Montéclair

A contemporary of Hotteterre who also makes a distinction between 𝇍 and 2[/2] is Michel Pignolet de Montéclair (1667–1737). In his Principes de Musique from 1736 he explains that one interpretative difference between the two metres manifests itself in a distinct treatment of the eighth notes. In this sense, Montéclair’s directives are highly similar to those by Hotteterre.

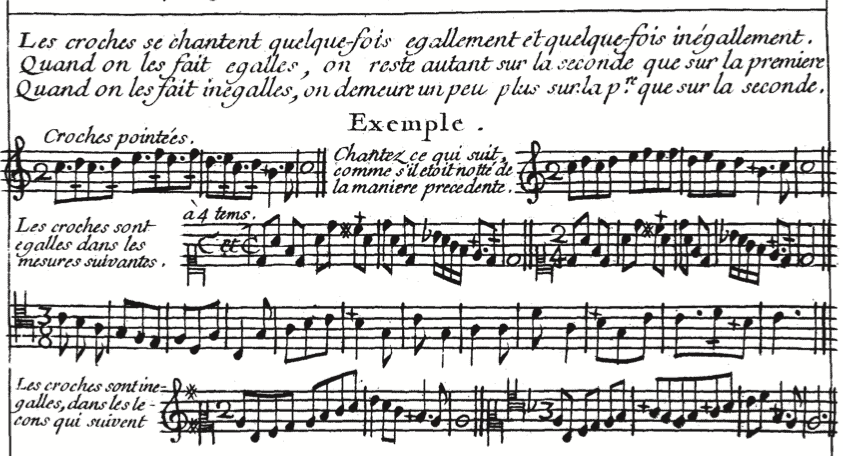

“Eighth notes are sometimes sung equally and sometimes unequally. When one performs them equally, one stays as long on the second as on the first. When one performs them unequally, one stays a little longer on the first than on the second. For example:

Sing what follows, as though it were notated in the preceding manner:

The eighth notes are equal in the following metres.

The eighth notes are unequal, in the exercises that follow.”

public domain, available on https://imslp.org;

modified translation from Keffer, Principes de Musique — Translation, p. 69–70

So, as does Hotteterre, Montéclair advocates to play the eighth notes in C barré equally, in 2[/2] unequally.

(To assess whether inégalité applies only to stepwise motion, see my essay https://essaysonmusic.com/what-is-inegalite-inequality-in-french-baroque-music/.)

This view is further confirmed on the next page of the treatise. The following example is set in 2, and Montéclair stipulates that the eighth notes should be played unequally and with a mouvement in two light beats:

Principes de Musiques (1736), p. 31, public domain,

available on https://imslp.org

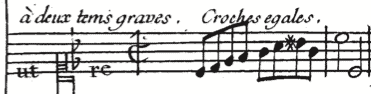

As for the following example, it is set in 𝇍, and Montéclair stipulates that the eighth notes should be played equally and with a mouvement à deux tems graves (in two slow/heavy beats):

Principes de Musiques (1736), p. 31, public domain,

available on https://imslp.org

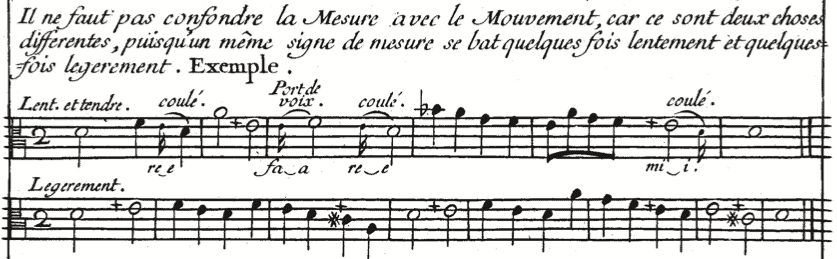

At first sight, Montéclair seems to agree with Hotteterre with the association of 2 with fast and 𝇍 with slow. Still, Montéclair is less formal about this:

“Metre should not be confused with mouvement, as they are two different things, since the same metre is sometimes beaten slowly and sometimes lightly. For example: …”

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

The examples above illustrate that, according to Montéclair, 2[/2] could be used for both slow and fast(er) tempos.

That said, he does agree with Hotteterre that 𝇍 comes in two metric organizations:

“When the C is crossed through, 𝇍, the time signature is beaten in four light beats. … The 𝇍 is sometimes beaten in two beats; in that case, half of the notes in the bar [i.e. all the notes of the first half of the bar] are put in the downbeat and the other half in the upbeat. …”

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

Pierre (L’Abbé) Duval

Pierre (L’Abbé) Duval (1730–1797) published in 1764 his Principes de la Musique Pratique Par Demandes et Par Réponses, a treatise conceived in the form of questions and answers. (Duval was a priest and university rector.) Having asked and explained what a duple metre is, he continues as follows:

“Q[uestion]. Which signs are used to indicate this metre?

A[nswer]. The number 2 or the letter C crossed through perpendicularly is used.

Q. Why two different signs to indicate that metre?

A. Because C barré indicates that the metre is slower than when it is marked with the number 2.”

So, Duval’s views on tempo of 𝇍 and 2 are in line with what Hotteterre and Montéclair advocate. Let’s see now what he writes about the performance of the eighth notes in both metres:

“Q. How should one beat this metre?

A. It is beaten from the bottom up, so that the first beat is called frapper (downbeat), and the second lever (upbeat).

…

Q. How should one play the eighth notes in that metre?

A. It is necessary that the first, third, fifth, etc. are much longer than the second, fourth, sixth, etc. That is called pointer les croches.”

Contrary to Hotteterre and Montéclair, Duval does not make a distinction between the performance of eighth notes in 𝇍 and 2. In both metres, he wants them to be played unequally, and quite strongly. (It would appear that the normal way of playing unequally was rather moderate, though. For more information, see again my essay https://essaysonmusic.com/what-is-inegalite-inequality-in-french-baroque-music/.) And Duval does not mention either the possibility of beating 𝇍 in four (light) beats; for him, that metre is a genuine duple metre, as is 2[/2].

Further Reading (Selection):

- Duval, Pierre (L’Abbé). Principes de la Musique Pratique Par Demandes et Par Réponses (Paris, 1764).

- Hefling, Stephen E. Rhythmic Alteration in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Music: Notes Inégales and Overdotting (New York: Schirmer Books, 1993).

- Hotteterre, Jacques-Martin. L’Art de Préluder sur la Flûte Traversière (Paris, 1719). English translation in: Jacques Hotteterre’s L’Art de Préluder — A Translation and Commentary, ed. Margareth Anne Boyer (University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1979).

- Montéclair, Michel Pignolet de. Principes de Musique (Paris, 1736). English translation in: Michel Pignolet de Montéclair: Principes de Musique Divisez en Quatre Parties (Paris, 1736), Translation and Commentary; ed. Constance Barbara Keffer (University of Arizona, 1977).