This is a follow-up on my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? to broaden one’s understanding of the practice of rhythmic inequality (notes inégales). It focusses on six terms/concepts used by 17th– and 18th-century French writers related to inégalité or to other performance-practice features that often cause interpretative problems for modern-day performers of French Baroque and galant repertoire.

Pointer, marquer, piquer, appuyer, lourer and mesuré are terms used by 17th– and 18th-century French writers to refer to a certain type of inégalité or to some other aspect of performance practice. Except mesuré, however, there is no consensus on any term.

In this essay, I will explain the different meanings of each term mentioned above based on citations from historical sources and prescriptions in scores. At the end of my discussion of each term, I will summarize its possible different readings.

Pointer

The term pointer is often used by French writers to refer to the practice of playing unequally. Jacques-Martin Hotteterre le Romain (1673–1763), for instance, uses pointer in this sense multiple times in the important chapter on time signatures from his treatise L’Art de Préluder sur la Flûte Traversière from 1719. (Hotteterre was probably called the Roman because he stayed and worked in Rome from 1698 to 1700.) Below you find the first occurrence of pointer in this chapter, explaining what it stands for in the context of his discussion of the “Bar with 4 slow beats”:

“…the sixteenths in this time signature must be pointées, that is, one long and one short. …”

public domain, available on https://imslp.org; my translation

A couple of years earlier, François Couperin (1668–1733) refers to pointer in the same meaning in his treatise on harpsichord playing and related aesthetics L’Art de toucher Le Clavecin , albeit, compared to Hotteterre, only briefly. Below is an excerpt from the statement I already dealt with in my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? ):

“For example, we point several eighths that proceed by conjunct degrees; however, we mark them equal!”

translation from Hefling, Rhythmic Alteration, p. 12

Note that the expression “nous les marquons” means here “we write them” and has no musical connotation; for the different musical meanings of the term marquer, see below.

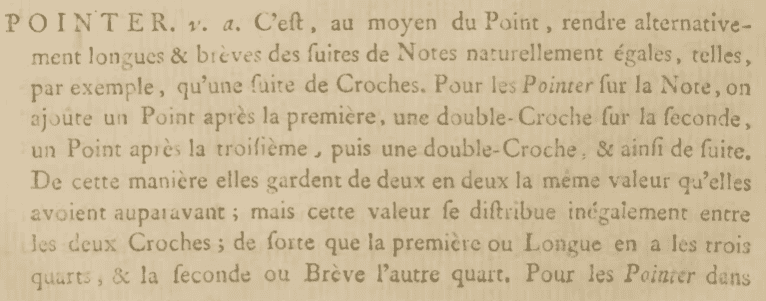

The composer and philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) also uses the term pointer to refer to inequality in his Dictionnaire de Musique from 1768:

“POINTER. Attributive verb. It is, by means of a dot, to make sequences of naturally equal notes alternately long and short, such as, for example, a sequence of eighth notes. To pointer them on the note [in the score], one adds a dot after the first, a sixteenth note on the second, a dot after the third, then a sixteenth note, & so on. In this way they keep two by two the same value they had before; but this value is distributed unequally between the two eighth notes; so that the first or long one has three quarters of it, & the second or short one the other quarter. To pointer them in the execution, they are passed unequally according to these same proportions, even if they were notated equally. In Italian music all the eighths are always equal, unless they are marked Pointées. But in French music one makes the eighths exactly equal only in the four-beat meter [C]; in all the others one always makes them a little unequal, unless they are marked Croches égales.”

When one stops reading after the second line of page 387, it would appear that Rousseau advocates a fairly sharp inégalité —with a 3:1 ratio— as the standard. Yet in the following paragraph, he makes clear that he isn’t, that he adheres to the common view of mild inequality. After all, he states that “on les pointe toujours un peu”. (See also my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? regarding the consensus on this gentle form of this inégalité.) This is an important observation. Indeed, pointer does not necessarily imply an actual 3:1 ratio, as if one were to play exact dotted rhythms, but is a term to refer to playing unequally, regardless the ratio.

For some writers, however, pointer does mean sharp inequality. One of those writers is Étienne Loulié (1654–1702). As I have explained in my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? , he discusses piquer or pointer as a sharp form of inequality in any time signature and particularly in the context of ternary time signatures, yet one that should be asked for by the composer by means of written dotted rhythms (Éléments ou Principes de Musique , 1696):

“There is still a third way, in which one makes the first half-beat much longer than the second, but the first half-beat must have a dot. One calls this third way Piquer, or Pointer.”

(More on the term piquer below.)

The term pointer does not only prescribe playing unequally but could also refer to playing staccato. In fact, both interpretations simply correspond to the literal meaning of the French word pointer: adding a dot. (In the case of sharp inégalité, a dot occurs or is mentally added after the uneven notes, while staccato notes are recognized by dots occurring above or below them.) Consider the next citation, which is an excerpt from the Dictionnaire de Musique from 1787 written by the French composer and writer Chevalier de Meude-Monpas (fl. ca. 1780–1790):

“POINTER, neutral verb. It is putting dots after notes to increase their value by half. Dots are also sometimes placed over quarter notes, eighth notes and sixteenth notes, to indicate to the performers that they should be detached and marked in a brisk and sensitive manner; but these dots add nothing to the value of the notes: they merely designate a brisk genre.”

In summary, pointer can have (at least) three meanings:

- To play unequally as a general term (and thus in a variable manner)

- To play unequally in a sharp manner

- To play notes staccato and briskly (and not necessarily rhythmically unequally)

Marquer

Depending on the writer, marquer can have different, even opposing, meanings. As far as I know, the earliest source that mentions this term is the Traité de la viole from 1687 written by the French viol player and composer Jean Rousseau (1644–1699), not to be confused with Jean-Jacques Rousseau. As the following directives illustrate, marquer means to play unequally for Rousseau:

“Under the signature of four beats, the eighths must be touched/played equally, that is, one should not marquer any of them: but as regards the sixteenths, one should marquer a bit the first, third, etc.

Under the signature of two beats, in the Airs de Mouvement with regard to the eighth notes, one should marquer a bit the first, third, etc. of each bar; but one should take care not to marquer them too roughly.

Under the signature of three beats with regard to the eighths, one should marquer a bit the first of each bar, and play the others equally: One should observe the same thing in 3/2 with regard to the quarter notes, in the Airs de Mouvement.”

Exactly the opposite interpretation of the term —marquer as a synonym for playing equally— is apparently given by Loulié in the annotations he made himself to his Éléments ou Principes de Musique from 1696 (F-Pn f.fr.n.a. 6355). (This information is mentioned by Stephen Hefling in his monograph Rhythmic Alteration in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Music — Notes Inégales and Overdotting (New York: Schirmer Books, 1993, p. 22). Unfortunately, however, I was not able to verify the source myself.)

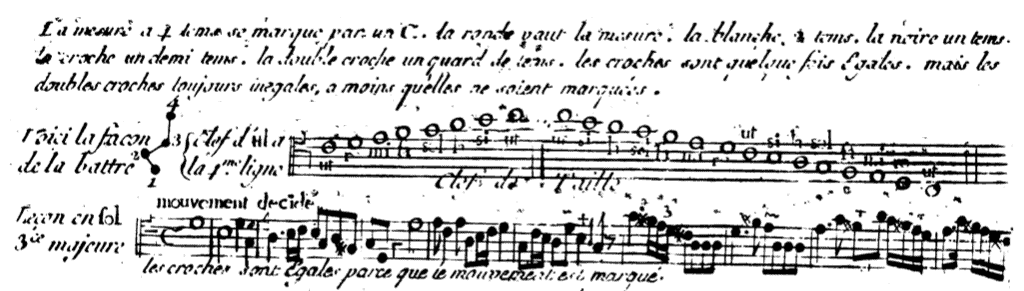

And then there is a writer such as the ‘Belgian’-born French maître de musique Antoine Morel de Lescer (1718–1781), who gives conflicting views in his treatise on singing Sçience de la Musique Vocale from ca. 1760. First, he states the following:

“… The eighth notes are sometimes equal, but the sixteenth notes [are] always unequal, unless they are marquées. [Music example] … The eighth notes are equal because the tempo/character is marqué.”

available on https://books.google.com; my translation

Note that Morel de Lescer’s view that eighth notes in a 4/4 time signature can be performed unequally had become the exception at the time of this treatise.

From this quote, it would appear that Morel de Lescer unequivocally associates marquer with playing equally. Yet three pages further in his treatise, he gives an example with the indication Mouvement marqué and the directive that, contrary to what one might expect, “the eighth notes and the sixteenth notes must be unequal”:

The fact that both the eighth notes and the sixteenths notes should be performed unequally is an illustration of cumulative inégalité; see my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? .

A third meaning of the term marquer is given by the French lexicographer and composer Sébastien de Brossard (1655–1730) in the entry Motto of his Dictionnaire de Musique from 1703. He starts by explaining that the term Motto, or Mouvement, has different meanings, one of which refers to tempo. In reference to this meaning, he states the following:

“… Sometimes it [Motto] means the slowness or the speed of the notes and of the bar, the reason why one says mouvement gay, mouvement lent, mouvement vif, or animé, etc. and in this sense, it often also means an equality, fixed and well marked, of all the beats of the bar. It is in this sense that one says that the recitative is not sung in a [fixed] tempo; that the minuet, the gavotte, the sarabande etc. are airs de mouvements, etc.”

my translation

So, de Brossard does not link the term marquer with playing unequally or equally but uses it to indicate playing in strict time, something not done in a recitative.

A fourth meaning of the term marquer is given by, amongst others, the French organist, composer and pedagogue Michel Corrette (1707–1795) in his Méthode pour apprendre aisément à joüer De La flûte traversière from ca. 1740. Following the paragraph about the 6/4 time signature and the genres suited for that time signature, he states the following:

“These Airs must be played in a noble manner by well marquant the quarter notes; and by pointant the eighths two by two.”

So, he seems to understand marquer as something we might translate as to give prominence to (and pointer as to play unequally).

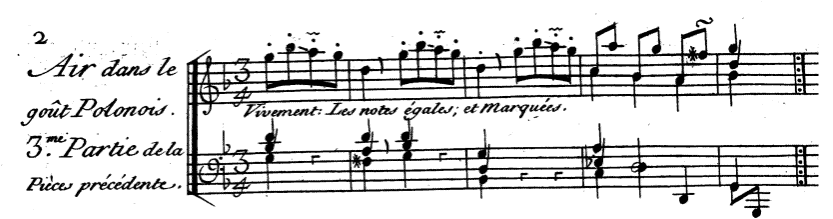

It would appear that François Couperin interpreted the term marquer in this sense as well, at least partly. In the indication to the Air dans le gout Polonois from his fourth book of harpsichord pieces, Couperin asks for equal notes that should also be marquées:

Still, once in the second book and once in the third book, Couperin asks for Légérement, [sic] et marqué, an indication that seems somewhat conflicting. Below you can see the example from Book 3:

One could argue that the prescription marqué in the example above might refer to playing strictly in time. This interpretation, however, seems to be invalidated somewhat, at least with regard to Book 4, by an indication of a piece in that book that includes both the term marqué as the prescription d’une grand précision (with great precision):

In summary, marquer can have (at least) four meanings:

- To play unequally

- To play equally

- To play in strict time

- To give prominence

Piquer

French writers do not agree on the meaning of the word piquer (or picquer) either. As I have mentioned above (see also my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? ), Loulié uses this term as synonymous with pointer, both of which stand for sharp inequality as one of four ways to perform the smallest regular notes in any time signature and particularly in ternary time signatures, provided that the dotted rhythms are written in the score. Below you find once more how he describes this type of inequality in his Éléments ou Principes de Musique from 1696:

“There is still a third way, in which one makes the first half-beat much longer than the second, but the first half-beat must have a dot. One calls this third way Piquer, or Pointer.”

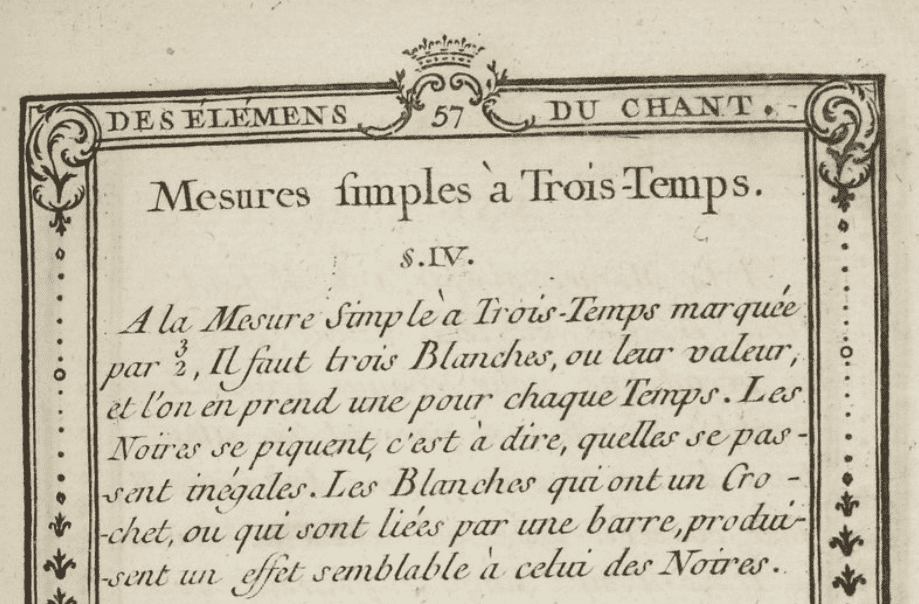

As for Joseph Lacassagne (?1720–?1780), in his Traité Général Des Élémens Du Chant from 1766, he simple equates piquer with playing unequally:

“… The quarter notes se piquent, that is, are played unequally…”

public domain, available on https://gallica.bnf.fr; my translation

The fact that Lacassagne equates piquer with playing unequally could be related to his view that inégalité in general should be (rather) sharp:

“… The eighth notes are played unequally, that is, that the first one is much longer than the second one in proportion to the mouvement one performs…”

public domain, available on https://gallica.bnf.fr; my translation

These views on piquer, however, do not seem to have been the dominant ones. The more common meaning of this term seems to have been (vigorous) staccato playing. In his Dictionnaire de Musique from 1703, de Brossard explains staccato as follows:

“STACCATO or Stoccatò means almost the same thing as Spiccato. That is to say that particularly the bowed instruments must take their bow strokes dry, without drawing-out, and well detached or separated one from another; it is almost what we call in French Picqué or Pointé.”

Hefling, Rhythmic Alteration, p. 171 footnote 16

So, just as is the case for Loulié, the terms piquer and pointer are interchangeable for de Brossard, yet not as an indication of sharp inequality.

Using the term piquer for a spirited fashion of staccato playing is further advocated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau:

“PIQUÉ, adj. used adverbially. Manner of playing by dotting the notes and strongly marking the dotted one.

Notes that are piquées are rows of notes ascending or descending diatonically, or restruck on the same pitch, above each of which one places a dot (which is sometimes a bit elongated [i.e., a stroke]) to indicate that they must be equally marked by tongue strokes or by dry and detached bow strokes…”

Hotteterre, too, seems to view piquer in this way. Let’s re-examine the example given in my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? —his first Trait in A major:

available on https://imslp.org

Towards the end of this example, Hotteterre writes not only dots below the eighth notes but also the word piqué below the first group of eighth notes, probably to clarify that those notes should not only be played short but also energetically. (His prescription that the eighth notes must be performed equal is mentioned already at the beginning of this Trait.)

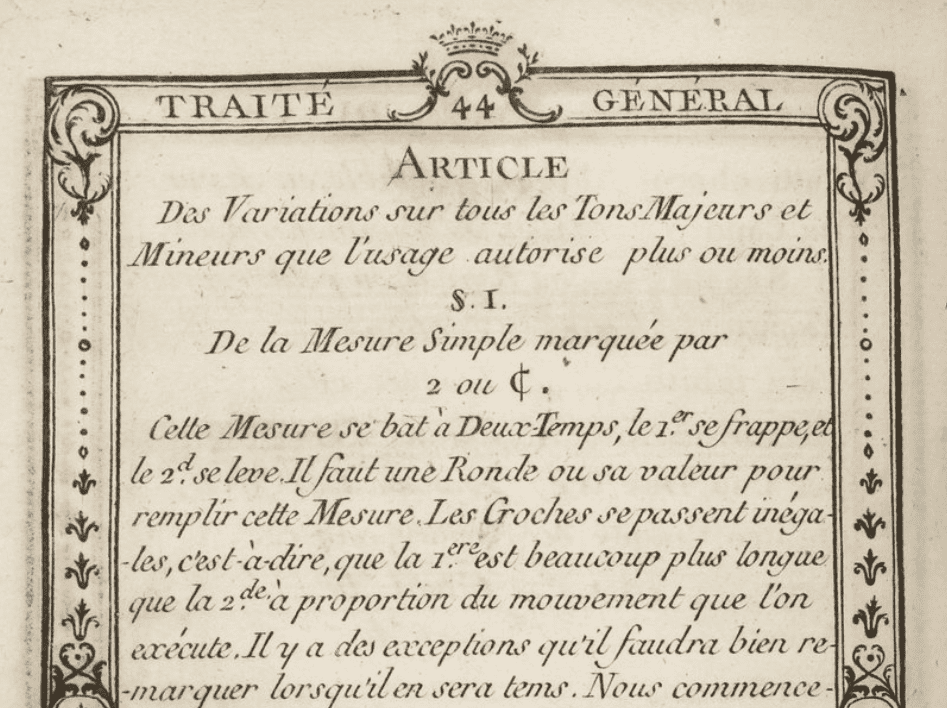

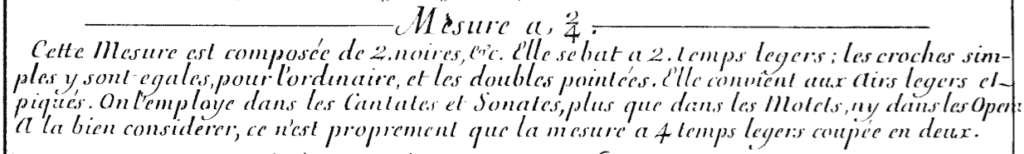

That Hotteterre relates the term piquer to articulation and character rather than to playing (un)equally is further confirmed by the several descriptions in his chapter on time signatures. Below I have reproduced the beginning of his discussion of 2/4:

“This time signature consists of two quarter notes, etc. It is beaten in two light beats; the simple eighth notes are usually equal, and the sixteenth notes pointées [unequal]. It is suitable for the Airs legers [light] et piqués…”

available on https://imslp.org; my translation

Hotteterre explains here which notes should be rendered equally and which ones unequally, before using the adjective piqués as a characterization for the airs suitable for this time signature.

In summary, piquer can have (at least) three meanings:

- To play unequally

- To play unequally in a sharp manner

- To play staccato (and briskly, whether or not equally)

Appuyer

In my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? , I mention that the French composer, author, and teacher Michel Pignolet de Montéclair (1667–1737) used yet another term to prescribe inequality: appuyer. Let’s re-examine the example given in that essay:

“When a quarter note followed by two eighth notes meet during one beat of a [2] time signature, one should stay on the quarter note during the [first] half of the beat, and then pass on to the two eighth notes on the other half of the beat, thereby appuïant the voice somewhat more on the first eighth note than on the second; that second eighth note must pass somewhat faster than the first one.”

public domain, available on https://imslp.org; my translation

Note that Montéclair prescribes here rendering both leaping eighth notes as eighth notes moving by stepwise motion unequally. Other writers limit inégalité to eighth notes moving by stepwise motion. For more information, see my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? .

François Couperin, for his part, uses the term appuyer in the context of short-long instead of long-short inequality in which the even instead of the uneven notes are lengthened. (For the exceptional character of this type of inequality, see my essay What is Inégalité (Inequality) in French Baroque Music? .) Below you find the explanation of this type of inégalité from Couperin’s ornament table:

“Slurs, wherein the dots indicate that the second note of each beat must be more stressed/lengthened.”

Rhythmic Alteration, p. 14

In his Méthode De Musique Sur Un Nouveau Plan from 1769, the French theorist Pierre-Joseph Roussier (1716/17–1792) seems to use the term in yet another sense, rather relating it to metre than to inégalité:

“With regard to the divisions of the beats, if each beat consists of two quarter notes, or of two so-called equal eighth notes, the first of those notes is appuyée, & the other is only passing; or if you wish, the first is strong, & the other is weak…”

my translation

Although related, this approach to metre with its ‘good’ and ‘bad’ notes —one of the most important umbrella concepts of the performance practices of the 17th and the 18th centuries— is not identical to the practice of notes inégales. Even when notes are performed rhythmically equally, that is, when the start of every note is rhythmically ‘correct’, it was customary to perform them differently, shortening and weakening the ‘bad’ notes. (For more information, see the chapter On Metre in my book Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue — Performance Practice Based on German Eighteenth-Century Theory (2013), p. 53–82.)

In summary, appuyer can have (at least) two meanings:

- To play unequally (also according to short-long pairing)

- To differentiate between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ notes (although not necessarily including inégalité)

Lourer

In general, the term lourer is used by French writers for mild inégalité. Loulié, for instance, uses this term in this sense as the second way to perform the smallest regular notes in any time signature and particularly in ternary time signatures:

“2° One makes the first half-beats sometimes a bit longer. This way is called Lourer. One uses it in the melodies in which the tones follow each in stepwise motion.”

Note that, according to Loulié, this type of inégalité only applies to notes moving in stepwise motion.

De Brossard, for his part, makes a clear distinction between lourer on the one hand and pi(c)quer or pointer on the other, at the same time referring to a difference in strength between the uneven and the even notes:

“Lourer. It is a way of singing that consists in giving a little more time & strength to the first of two notes of similar value, such as two quarter notes, two eighth notes etc., than to the second, without however pointer or picquer it.”

As for the priest and writer Demoz de la Salle (ca. 1681–ca. 1746), he explains in his Méthode De Musique from 1728 that:

“LOURER, It is to render the notes tied in pairs by this figure [slur] through slurring, caressing, and rolling them in such a way that the sounds are continuous, tied, and conjoined … marking perceptibly the first note of the pair…”

Rhythmic Alteration, p. 170, footnote 6

With regard to notes slurred two-by-two, it would thus appear that de la Salle advocates an inégalité that is more pronounced than, say, Loulié, although these notes should still be played quite gently.

As does de la Salle, the composer and writer Jean-François Boüin (ca. 1716–ca. 1781) also associates louré with “caressed and slurred notes” in his Vielleuse Habile from ca. 1761, although he does not mention the inclusion of inégalité:

my translation

In his Méthode Nouvelle from 1737, the composer and writer François David (ca. 1692–ca. 1757) uses the term lourer in another meaning, to describe triplets:

“… The Notes lourées are those that are often found in an even beat of the bar, where one accepts three whole notes or halve notes, or three quarter notes, or three eighth notes, or three sixteenth notes, for one beat, & for which only two are usually used…”

In summary, lourer/notes lourées can have (at least) four meanings:

- To play unequally in a mild manner

- To play unequally in a sharper yet gentle manner while slurring two-by-two

- Slurred and gently played notes (without inégalité?)

- Triplets

Mesuré

Several secondary sources claim that the term mesuré implies rhythmical equality, yet do so without referring to a single source. According to Judy Tarling, for instance, mesuré means “equal and in a measured fashion” (Tarling, Baroque String Playing, p. 164). In fact, neither Hefling nor I were able to find a single source from the 17th or the 18th century stating that mesuré cancels inégalité. As far as I know, mesuré is only used to prescribe a performance in strict time. One example, by François Couperin from his Art de toucher Le Clavecin , should suffice here:

“It is necessary that those who will use these regulated [non-improvised] preludes play them in an easy way, without being too concerned with the precision of the mouvemens [sic]; unless I have marked it expressly with the word mesuré…”

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Boüin, Jean-François. La Vielleuse Habile ou Nouvelle Méthode Courte, très facile, et très sûre Pour Apprendre a [sic] joüer de la Vielle (Paris, ca. 1761).

Corrette, Michel. Méthode pour apprendre aisément à joüer De La Flûte traversière (Paris, ca. 1740).

Couperin, François. L’Art de toucher Le Clavecin (Paris, 1716 and 1717).

David, François. Méthode Nouvelle Ou Principes Généraux Pour Apprendre Facilement La Musique Et L’Art De Chanter (Paris, 1737).

de Brossard, Sébastien. Dictionaire de Musique (Paris, 1703).

de la Salle, Demoz. Méthode De Musique Selon Un Nouveau Système Très-court, très-facile & très-sûr (Paris, 1728).

de Meude-Monpas, J. J. O. Dictionnaire de Musique (Paris, 1787).

Hotteterre, Jacques-Martin. L’Art de Préluder sur la Flûte Traversière (Paris, 1719).

Lacassagne, Joseph. Traité Général Des Élémens Du Chant (Paris, 1766).

Loulié, Étienne. Éléments ou Principes de Musique (Paris, 1696).

Montéclair, Michel Pignolet de. Principes de Musique (Paris, 1736).

Morel de Lescer, Antoine. Sçience de la musique vocale (Charleville, ca. 1760).

Rousseau, Jean. Traité de la viole (Paris, 1687).

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Dictionnaire de Musique (Paris, 1768). Pierre-Joseph Roussier. Méthode De Musique Sur Un Nouveau Plan (Paris, 1769).

Secondary Sources

Byrt, John. Some New Interpretations of the Notes Inégales Evidence, in: Early Music 28/1 (2000), 99–112.

Demeyere, Ewald. Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue — Performance Practice Based on German Eighteenth-Century Theory (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2013).

Fuller, David. Notes inégales (Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 8 Oct. 2022), https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000020126.

Hefling, Stephen E. Rhythmic Alteration in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Music: Notes Inégales and Overdotting (New York: Schirmer Books, 1993).

Kuijken, Barthold. The Notation Is Not the Music — Reflections on Early Music Practice and Performance (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013).

Tarling, Judy. Baroque String Playing for ingenious learners (St. Albans: Corda Music, 2000).