I have already explored the voice-leading pattern that Robert Gjerdingen calls a Prinner to some extend in four essays (The Traditional Prinner, Variants of the Prinner (Part 1), Variants of the Prinner (Part 2): Sequential Prinners and Variants of the Prinner (Part 3)). To that series I will add another essay, although from a structural point of view it might be questionable to label the schema discussed here as a Prinner.

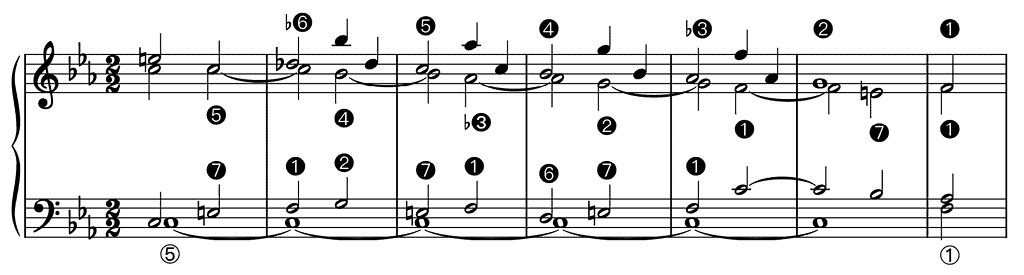

In this essay, I will explore what Gjerdingen calls the Stabat Mater Prinner. Its usual features are: a dominant pedal point, a ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent in the top voice and a metrically shifted (➎–)➍–➌–➋–➊ descent in the middle voice, resulting in a chain of 2–3 suspensions. It occurs in major and minor.

Besides illustrating different versions of this voice-leading pattern, I also argue that the Stabat Mater Prinner (henceforth SMP) does not actually function structurally as a Prinner, but as (the elaboration of ⑤ in the form of a dominant pedal of) a cadence. In that sense, the term Prinner does not seem ideal.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in all the parts except those in the bass, which I denote with white-circled figures. And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Where Does the Name Stabat Mater Prinner Come From?

In his important book Music in the Galant Style (henceforth MGS) from 2007, Robert Gjerdingen elaborates on several types of what he calls contrapuntal Prinners, i.e., Prinners that include a chain of 2–3 suspensions. In one of those types, the chain of 2–3 suspensions appears above a dominant pedal. Since one of the most famous instances of that voice-leading pattern occurs in the Stabat Mater by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710–1736), Gjerdingen named it after that composition.

What’s in a Name?

Gjerdingen’s decision to label the voice-leading pattern central to this essay a Prinner is in my opinion not quite satisfactory. In MGS, Gjerdingen defines a Prinner not only as a specific voice-leading pattern but also as “an elegant musical riposte [to an opening gambit], and one of the favorite choices” (Gjerdingen, 2007: 45). As far as I know, however, the SMP has never been used in that manner. The presence of the dominant pedal makes it indeed unsuited for that structural purpose. The SMP is rather used structurally in three ways:

- As an elaboration of ⑤ (dominant pedal) in an imperfect ⑤–① cadence or broken cadence

- As an elaboration of ⑤ (dominant pedal) in a perfect ⑤–① cadence or broken cadence

- As an elaboration of ⑤ (dominant pedal) in a half cadence.

Still, since the label Stabat Mater Prinner is widely accepted and used today, I will continue to use it.

(As a matter of fact, the presence of the dominant pedal (also) relates this voice-leading pattern to what Riepel calls a Ponte (Italian for bridge), although Riepel does not discuss the voice leading central to this essay and describes the Ponte as a gesture that starts the second half of a rounded binary form.)

Voice Leading

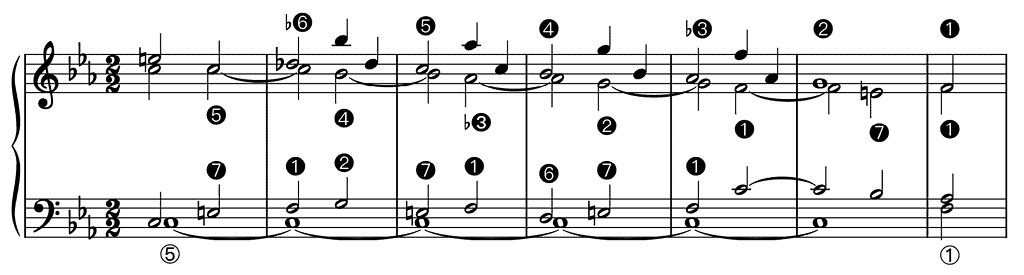

The voice-leading characteristics of the SMP, which is used both in major and minor keys, are:

- A ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent in the top voice

- A syncopated ➎–➍–➌–➋–➊ descent in the second highest voice

- A pedal point in the bass on ⑤

- In case a fourth part is present, it is usually a tenor part that produces a (➐–)➊–➋–➐–➊–➏–➐–➊ line or, only in major, a (➐–)♯➊–➋–➐–➊–➏–➐–➊ line.

Note that I left the bass empty in the last bar, for which there are several options.

The presence of the tenor part results in the moto del basso (bass motion) Second Up Third Down on a dominant pedal. This moto within a SMP is set with a 6/5 chord on the first bass note of each segment and a triad on the second bass of each segment. (For more information on the Second Up Third Down see my essay Disjunct Moti del Basso.)

When the key is major and the tenor part starts with ♯➊, one might be tempted, as does Gjerdingen, to label the first two segments of the Second Up Third Down within the SMP a Fonte. However, I am less inclined to do so since a genuine Fonte has its place after the double barline in a rounded binary form. As for the third segment and the following sonority, Gjerdingen describes them as Long Comma, i.e., a ➏–➐–➊ cadence.

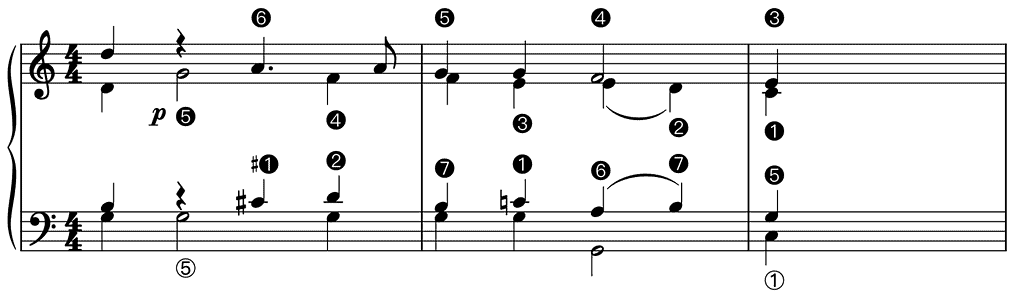

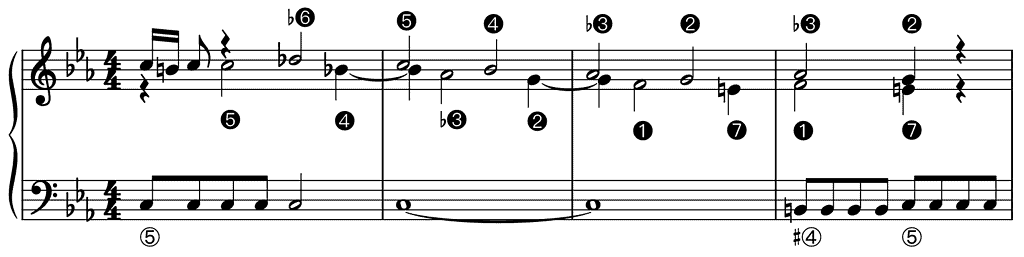

As an Imperfect ⑤–① Cadence or Broken Cadence

In this variant, ➌ of the ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent and ➊ of the syncopated ➎–➍–➌–➋–➊ descent can coincide with ① or with ⑥ that follows the dominant pedal point, a voice leading that works as an imperfect ⑤–① cadence or broken cadence, respectively. Mozart was particularly fond of this type of SMP. The following examples are just three of many he has written, one in minor with a SMP as an imperfect ⑤–① cadence and two in major, the first with a SMP as an imperfect ⑤–① cadence as well, the second with a SMP as a broken cadence.

As you can hear, the SMP in the example above is the conclusion of a dominant pedal point that started already four bars earlier.

To conclude the first phrase of the Gloria from his Mass in C major KV262, Mozart uses a SMP in major with a tenor part that starts on ♯➊, a SMP that works here as an imperfect ⑤–① cadence following a half cadence:

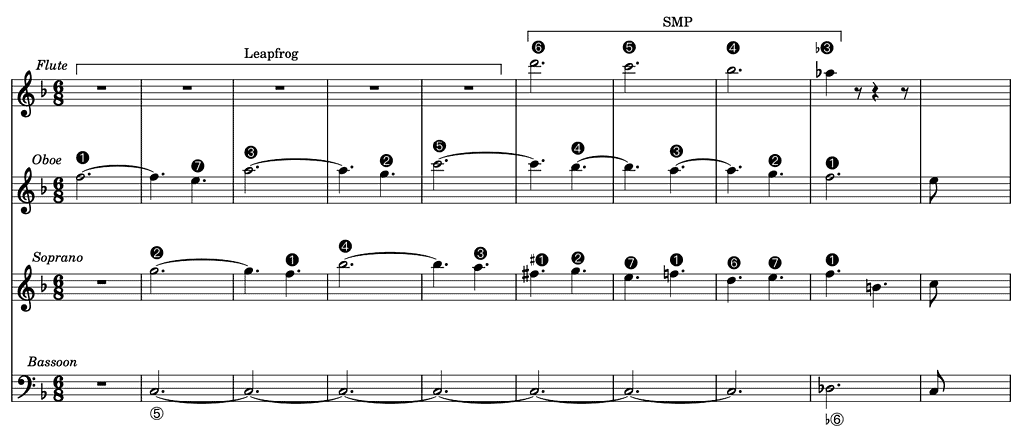

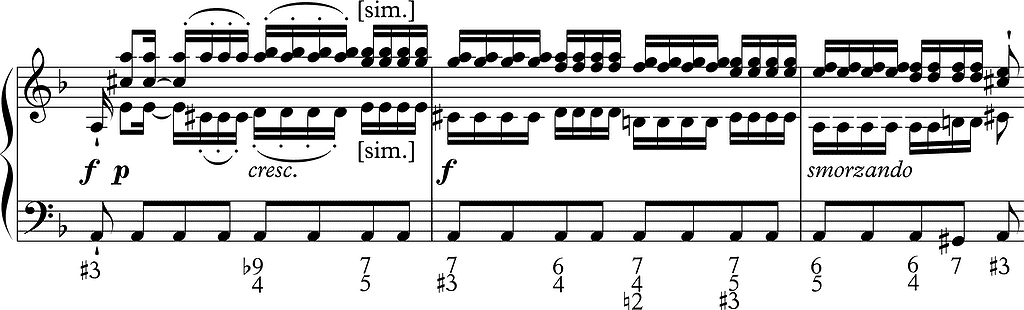

One of the most stunningly worked-out exemplars of a SMP in Mozart’s oeuvre is undoubtedly the one that appears in the cadenza at the end of the Et incarnatus est from the Great Mass in C minor KV427. To really appreciate its voice leading while listening, I have made a rhythmic reduction of this passage:

(The soprano Julie Fuchs is stunning; do listen to the complete aria.)

In this case, the SMP is preceded by a pattern in which the oboe and the soprano are engaged in a leapfrog, leaping over each other and creating 2–3 suspensions over a dominant pedal point. This SMP concludes with ♭⑥ and ♭➌ in the flute, thus working as a broken cadence, which in turn is followed by a half cadence.

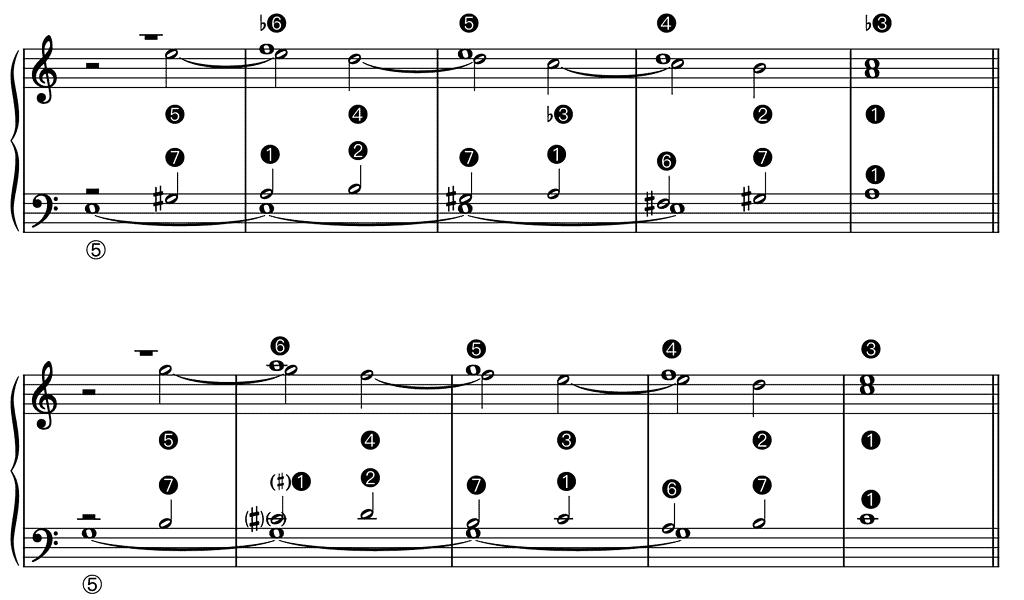

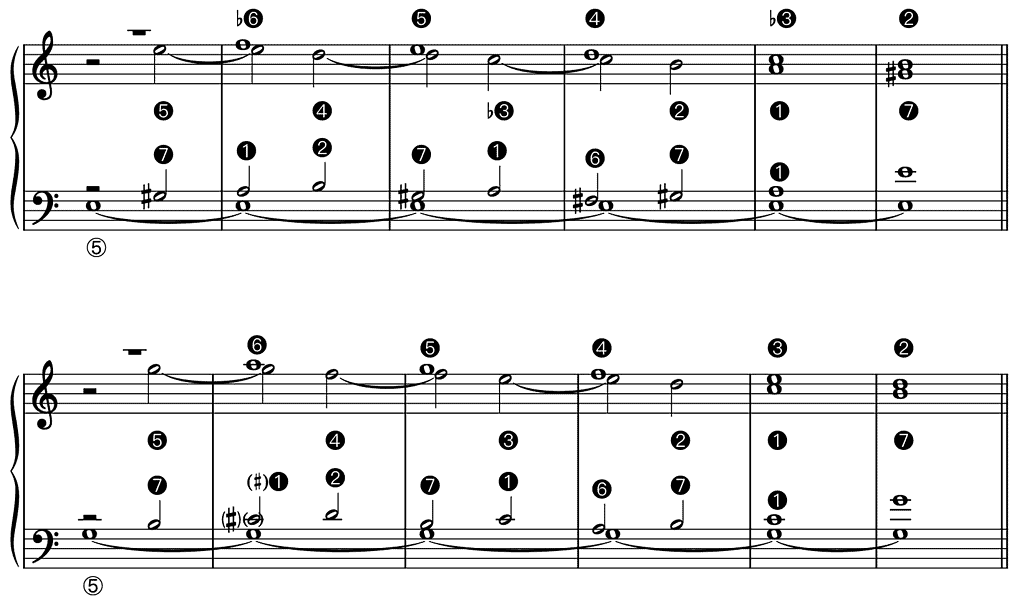

As a Perfect ⑤–① Cadence or Broken Cadence (Extended SMP)

In this variant, both descents in the upper voices are lengthened by two scale steps to create a perfect ⑤–① cadence and can conclude with ➊ above ① or ⑥. This example below illustrates this setting as a perfect ⑤–① cadence:

In this exemplar,

- the top part descends stepwise from ➏ to ➊

- the second highest part descends stepwise from ➎ to ➐ before stepping up to ➊

- after having produced its typical (➐–)➊–➋–➐–➊–➏–➐–➊ line, the tenor doubles the dominant before descending stepwise to the seventh on ⑤ and the third on ①. (Whether or not this tenor part is original is beyond the scope of this essay.)

As a Half Cadence (Extended SMP)

In this variant, both upper voices are lengthened by one scale step to create a half cadence:

Particularly in a minor key, ♯④ is often inserted in the bass just before the final triad, creating a diminished seventh. You can see and listen to this variant in a setting by Andrea Bernasconi (1706–1784) below. (Bernasconi was a successful Italian composer who devoted most of his career to opera, with numerous performances both in Italy and Germany. After 1772, he wrote only religious music. From 1753 to his death in 1784 he worked in Munich at the electoral court, first as assistant Kapellmeister, from 1755 as Kapellmeister after the death of Giovanni Porta (ca. 1775–1755).)

♯④ can also appear in an appended, second half cadence. In this case, it is usually set as a diminished seventh chord as well, a half cadence that Gjerdingen calls a Jommelli. (Gjerdingen labelled it as such in honour of Niccolò Jommelli (1717–1774), who often used this type of cadence.) This type of extended SMP appears towards the end of the opening movement of an undated Salve Regina in F minor for soprano, alto, two violins and continuo. This composition has been attributed to Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725) but on stylistic grounds, I would argue that it was almost certainly written by Pergolesi.

Note that flebile means plaintive.

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Prinner, Johann Jacob. Musicalischer Schlissl (1677).

Secondary Sources

Caplin, William E. Harmony and Cadence in Gjerdingen’s “Prinner”, in: What Is a Cadence? Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, ed. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015), 17–57.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).