In my previous three essays (Diatonic Moti del Basso that Rise Stepwise, Diatonic Moti del basso that Descend Stepwise and Chromatic Moti del Basso), I dealt with conjunct moti del basso, both diatonically and chromatically.

The topic of this essay is disjunct moti del basso, which are characterized by a sequential progression: a model that consists of a specific melodic bass interval and setting is transposed several times.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in all the parts except those in the bass, which I denote with white-circled figures. And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

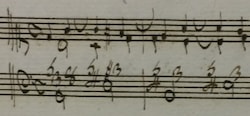

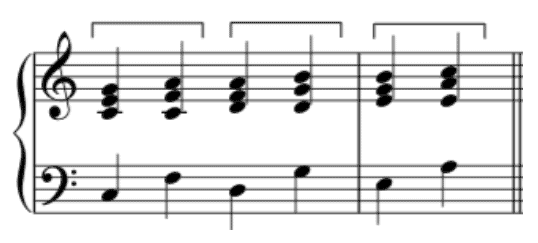

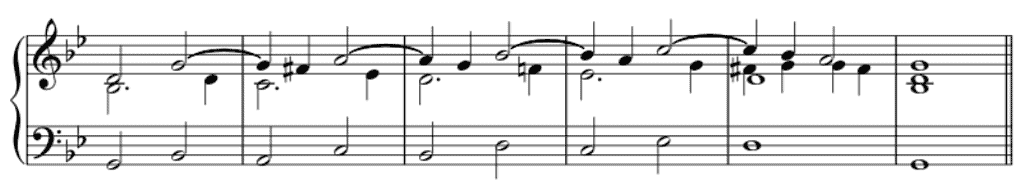

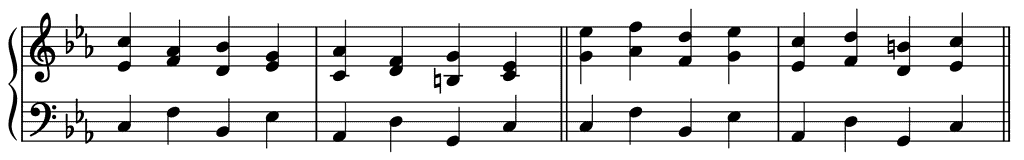

Compared to conjunct moti del basso, sequential construction is more prominent in disjunct moti; not only the bass but also the realization is usually sequential. The interval by which the segments of a sequence progress is almost always a second: a model is transposed several times a second up or down. (There is one exception, the Romanesca, whose model is transposed down a third instead a second twice.) In its schematic form, the model —and thus also all its transpositions— consists of two (different) bass notes that are described in the partimento tradition by the interval they form (for instance, Fourth Up or Third Down). From a metrical point of view, each disjunct pattern starts with a model in which the first note falls on a strong beat and the second note on a weak/less strong beat. To indicate how the model is transposed, a second interval is mentioned, describing the interval of the second note of the model and the first note of the first transposed segment. Consider the two examples below, both of which have the same model (Fourth Up).

The first example is a rising sequence (each next segment is a second higher than the previous one) while the second shows a descending sequence (each next segment is a second lower than the previous one). The rising sequence is called Fourth Up Third Down, the descending one Fourth Up Fifth Down.

The second example above also reveals an important observation regarding voice leading. While voice-leading rules are mostly observed within the model and its transpositions (for an exception see the moto 5–6/4+/2–6 from my essay Diatonic Moti del Basso that Descend Stepwise), they are less strict in between them. This explains why all voices descend at the beginning of both transposed segments.

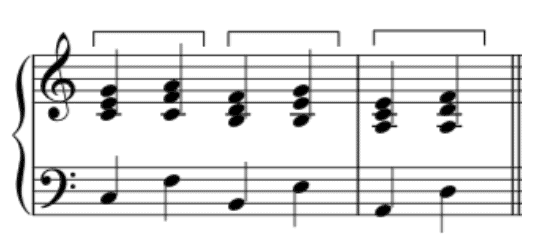

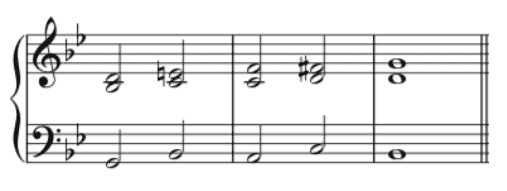

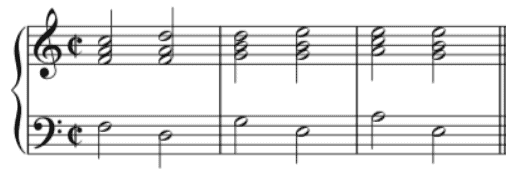

An interesting feature of a disjunct moto is the fact that a new pattern emerges when both bass notes (and chords) of each segment are metrically inversed. (However, not every moto has its metric complement applied.) A comparison of the next two examples shows how the interval pattern and accompanying realization are identical but metrically opposite, giving both patterns their own character and description. The first example is called Second Up Third Down, the second one Third Down Second Up.

Below, the disjunct moti are discussed in increasing order of model and transposition interval.

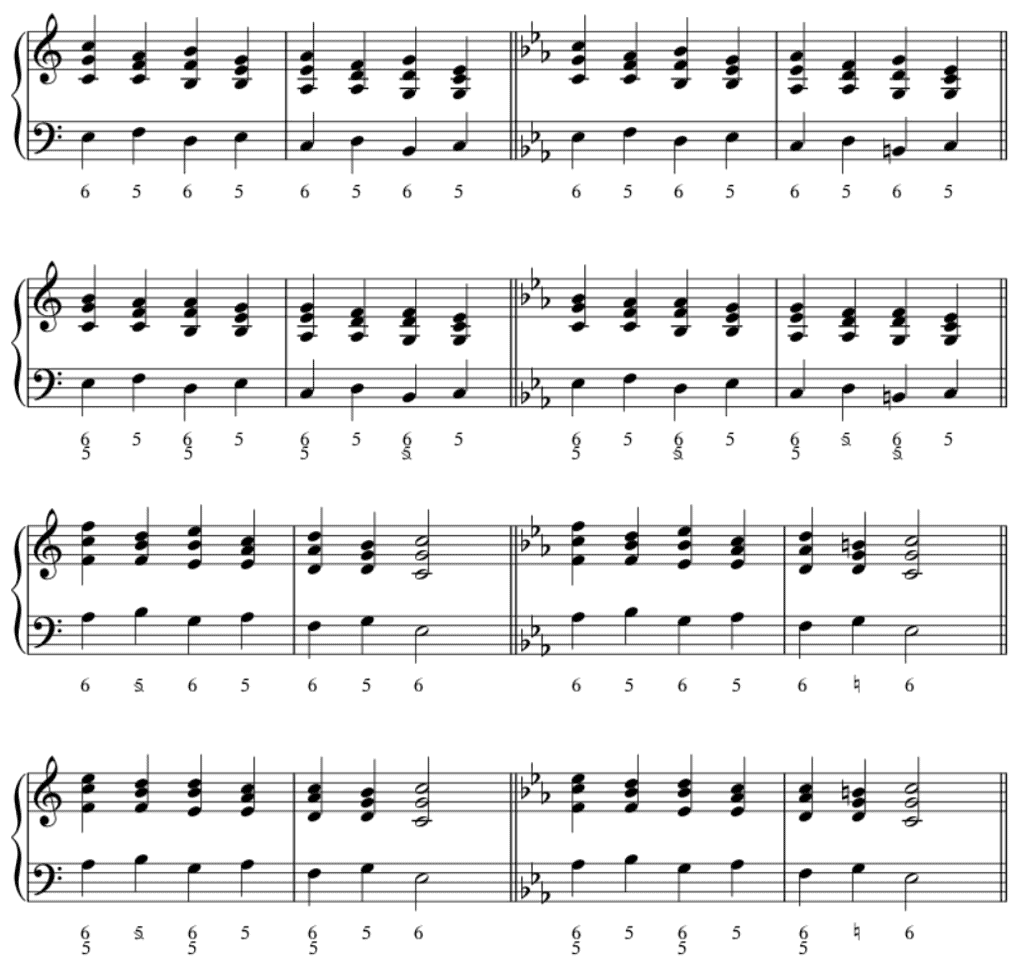

Second Up Third Down

This descending moto del basso occurs in both major and minor. In both cases, it is possible to start on (♭)③ and end on ①, or start on (♭)⑥ and end on (♭)③. Each strong beat is realized with a sixth chord or a 6/5 chord, each weak beat with a triad. Since this pattern opens with a sixth chord or a 6/5 chord, it is not suitable for opening a composition.

Second Up Down Third is not very common in partimenti as its metrical perception is not evident. Indeed, its realization tends to make it sound more like Third Down Second Up, resulting in a possible metrical shift. The reason for this is that a triad is more stable, more grounded than a sixth chord or 6/5 chord and is more associated with strong beats. Nevertheless, this pattern was treated as full-fledged within the partimento tradition, which more than legitimizes its existence.

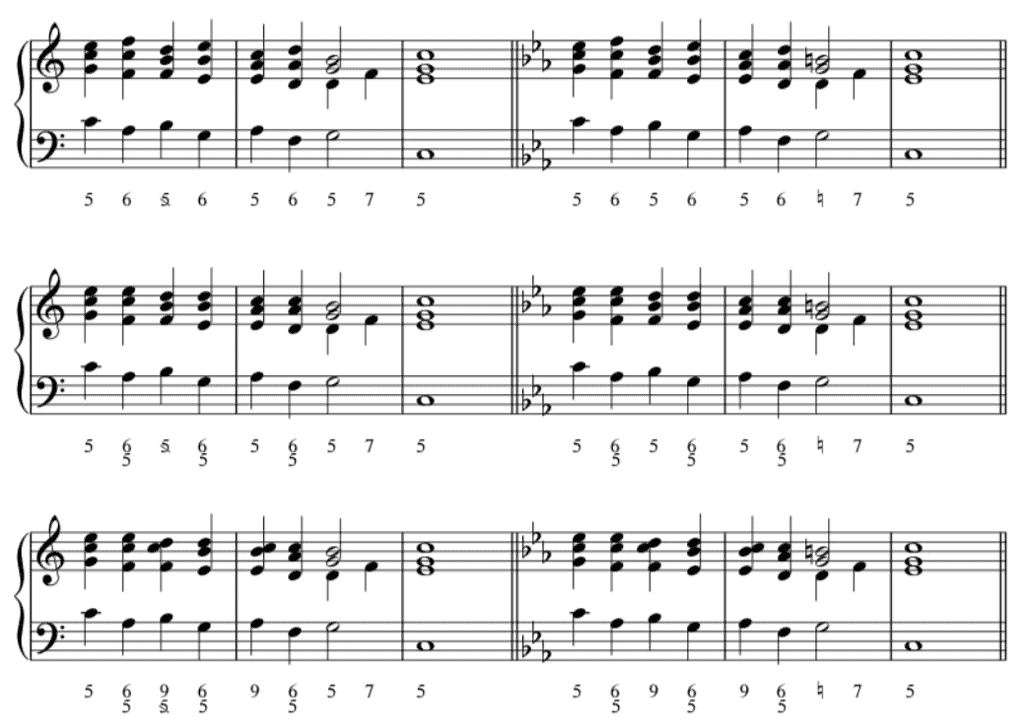

Third Down Second Up

This descending pattern, which unlike its complement Second Up Third Down, is in perfect agreement with metre. It also occurs in both major and minor, and usually starts on ① and ends ⑤, or starts on ④ and ends on ① (not shown in the example below). In a basic realization, the first note of each segment (on a strong beat) is realized as a triad, the second note (on a weak beat) with a sixth chord or 6/5 chord.

Third Up Second Down

For some moti, the harmonic situation does not allow the pattern to start in a strict way from the first bass note. As is the case with Third Up Second Down, a rising pattern that starts on ① and ends on ⑤, the realization model is not in the first but in the second bar. This moto occurs in major and minor, and exists in several realizations.

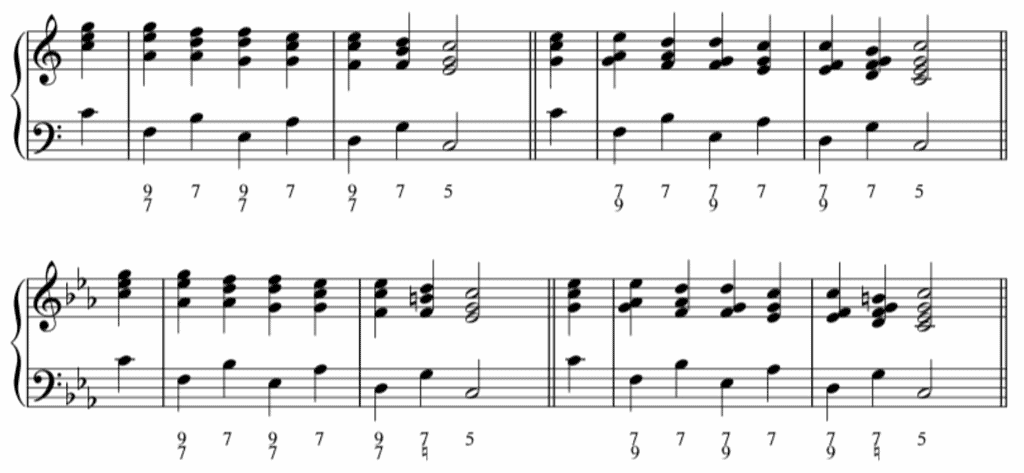

In the first realization, the first bass note of each segment (except of the model) is set with a 7–6 suspension, the second bass note as a sixth chord:

Note ♭➐ above the second bass note of the third segment.

This pattern also exists in a variant where, if possible, each descending second acts as local ②–① snippet, as a clausula tenorizans. In this variant, 4–3 suspension occurs on the first bass note of each segment:

In minor, a contrapuntal setting with rhythmically complementary upper voices should be opted for to make the f1 in bar 3 sound less abrupt and more ornamental:

If the pattern breaks off in minor after the first note of the third segment, a harmonically richer realization can be chosen with an unprepared (6/)4+/2 chord on the second note of the first two segments. In this case, both descending seconds in the bass act as (local) ④–③ snippets, twice as a clausula altizans:

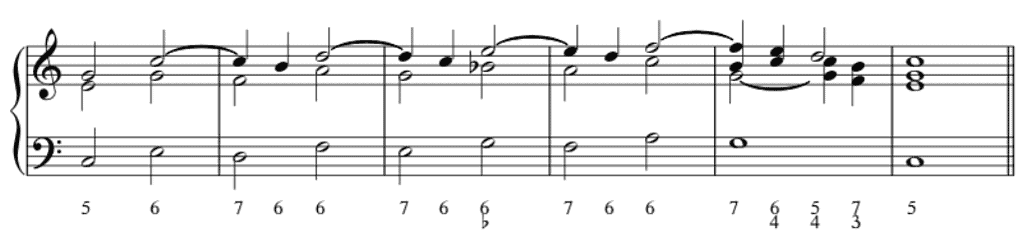

Fourth Down Second Up (aka Romanesca)

This moto, also known as the Romanesca or the Pachelbel bass, is also a movimento principale. (Since I have written several essays on this moto in my schemata series, I limit myself here to the essentials. For more information see https://essaysonmusic.com/schemata/.) It is the only moto whose model is transposed down a third instead a second twice.

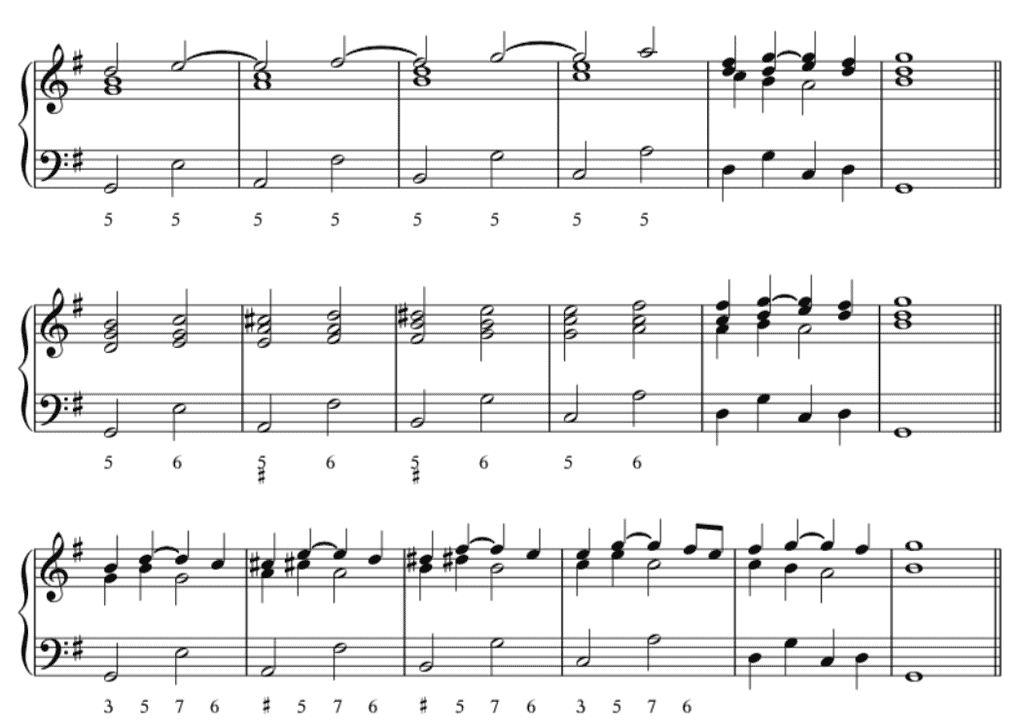

The Romanesca occurs in both major and minor and in both cases spans an octave. The version in major is characterized by two upper voices spanning a stepwise descent of a sixth in parallel thirds. Because of the specificity of the sixth and seventh scale steps in minor, its realization requires some extra attention. If one wants to preserve the stepwise descent of a sixth in an upper voice, one should chromatically lower the seventh scale step. Otherwise, ➐ should rise to ➊, resulting in breaking the stepwise descent.

There are also several realizations with one or two suspensions:

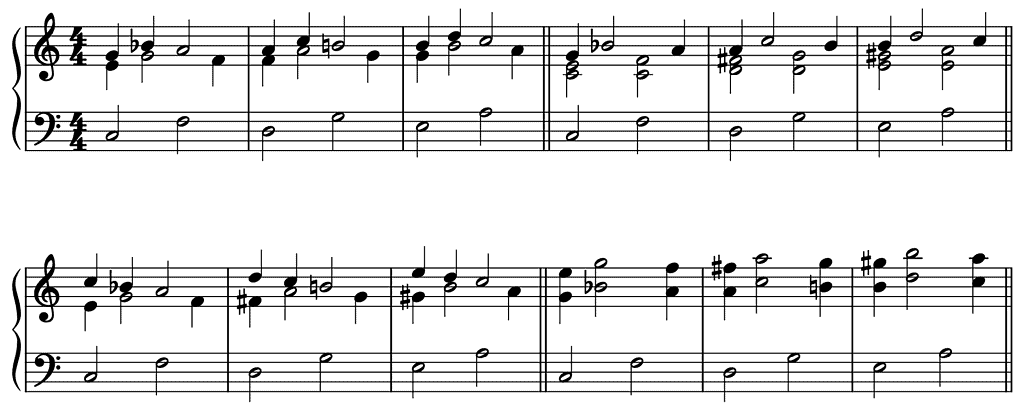

Fourth Up Third Down (aka Monte Principale)

This rising pattern usually occurs only in major. To make the difference between this pattern and the stepwise Monte clear, Gjerdingen added the adjective principale. (He chose this term because in early-nineteenth-century Italy, a pattern with only chordal roots in the bass was called a movimento principale.) As a variant, the first chord of each segment can include a major third, making each segment act as a local ⑤–① cadence or cadenza semplice.

This realization can be enriched by adding one or two suspensions:

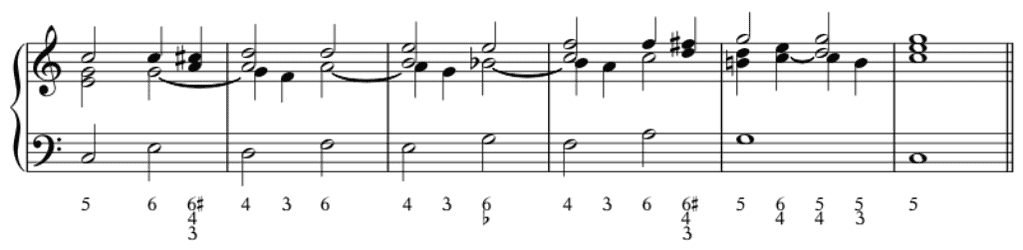

Fourth Up Fifth Down (aka Descending Circle of Fifths)

This descending moto del basso occurs in both major and minor. As is the case with a Monte Principale, this moto is realized in its basic version with triads only. The pattern can start on ① or on ④, resulting in metrically opposite configurations. Both usually ends on ①. And when ④ falls on a strong beat, it is often introduced by ① on the preceding weak beat.

Note that

- in the context of sequences, the melodic tritones ④–⑦ and ♭⑥–② in major and minor, respectively, were not considered a problem

- in minor, a scale mutation to the relative major occurs during the snippet ④–♭⑦–♭③, becoming a local ②–⑤–① snippet.

The Descending Circle of Fifths also occurs in a three-part variant with a chain of seventh suspensions:

There are also several realizations where ninth suspensions are added to ④, (♭)③ and ②:

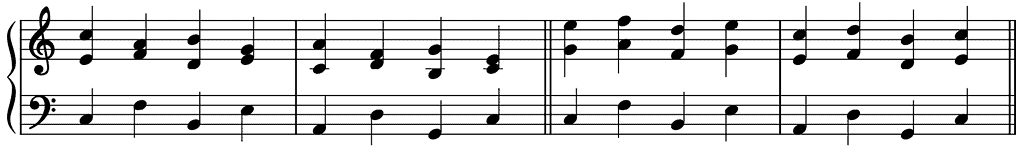

Fifth Up Fourth Down (aka Monte Romanesca)

This ascending circle of fifths is also a movimento principale. Gjerdingen gave this pattern the name Monte Romanesca since its model is more or less the same as that of the regular Romanesca (only the second bass note is an octave higher) but the transpositions rise rather than descend. Although the version of the Monte Romanesca with only triads was trained during partimento and composition lessons, mainly the variant with 4–3 suspensions was used in actual compositions. The latter variant is characterized by a canonic construction of the upper voices whereby each suspension is introduced with a melodic ascending fourth.

A Monte Romanesca occurs only in major and can have either two or three segments. In a version with three segments, the third segment is usually set locally as a ①–⑤ snippet, which also avoids the diminished fifth on the second bass note of that segment.

Fifth Down Fourth Up (aka Descending Circle of Fifths)

This moto is essentially identical to the Fourth Up Fifth Down. The only difference between the two moti is that every second bass note of a segment is in a different octave.

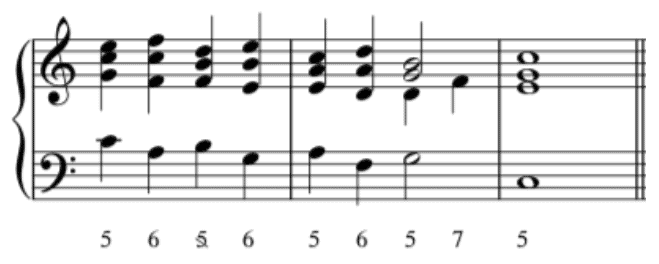

Sixth Up Fifth Down

A Sixth Up Fifth Down exists in two basic versions:

- realized as a movimento principale

- realized with alternating triads and sixth chords.

In the latter case, the melodic bass interval of each segment (except the fourth) acts as a local ⑤–③ snippet. This version of the Sixth Up Fifth Down is thus a Monte with exchanged outer voices. This version also occurs with a 7–6 suspension on the second note of each segment.

While a Third Down Fourth Up would produce a more obvious pattern from a melodic point of view, no such moto exists in the partimento tradition. However, this pattern does crop up for example in the exercises Mozart gave to his student Thomas Attwood:

Further Reading (Selection)

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).