In my essay Diatonic Moti del Basso that Rise Stepwise, I explain that each note of a diatonic ascending moto normally has minimum two sonorities per bass note. (There are of course alternative settings for the ascending RO with one sonority per bass note; see my essay The Rule of the Octave in Three Parts.) While several settings of a descending scale present two sonorities per bass note as well, another setting has only one sonority per bass note, alternating a triad with a sixth chord. (For the non-sequential setting with one sixth chord per bass note see again my essay The Rule of the Octave in Three Parts.) And another descending pattern contains only suspensions in the bass.

Stepwise Romanesca (Alternative for the Descending RO)

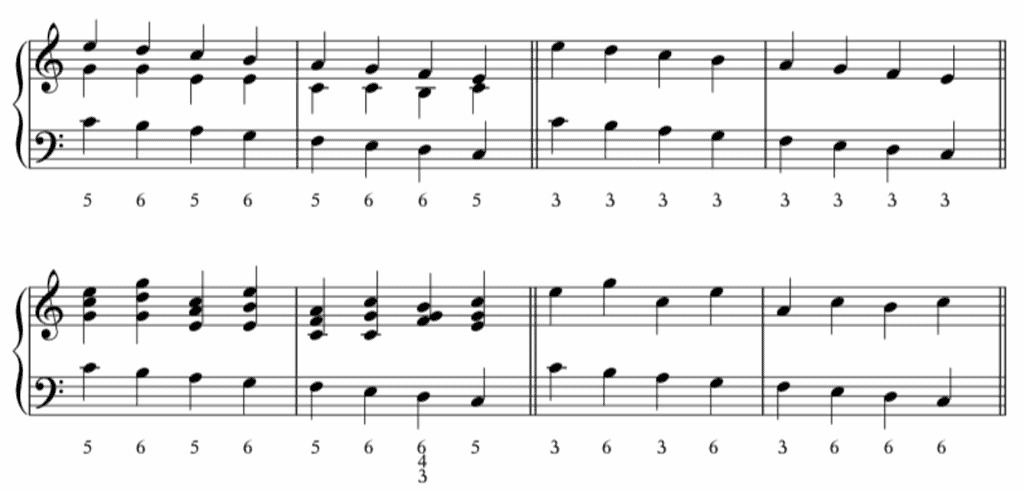

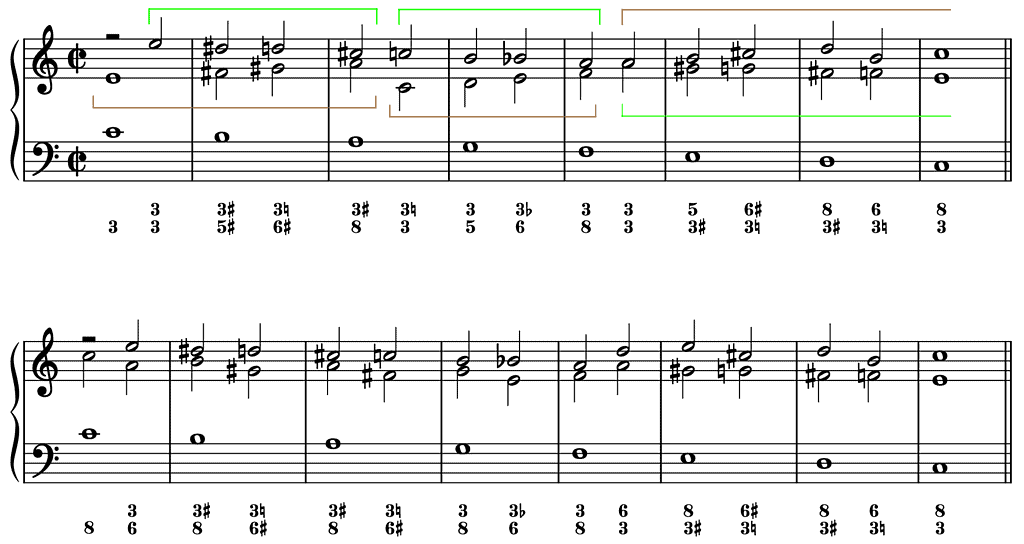

Unlike diatonic ascending moti, but in agreement with the RO, each bass note of the Stepwise Romanesca usually lasts one beat, implying that each bass note of this pattern is realized with only one sonority. The bass notes of the Stepwise Romanesca are alternately realized as a triad and a sixth chord. To span a full octave, the snippet ②–① is appended and set with a sixth chord and a triad, respectively. This setting results in a sequence in which each segment consists of two bass notes.

The Stepwise Romanesca occurs in both major and minor, spans a sixth in both modes and has two possible melodies:

- a stepwise melody that runs in parallel thirds with the bass

- a leaping melody resulting from the presence of alternating vertical thirds and sixths between the outer voices.

7–6

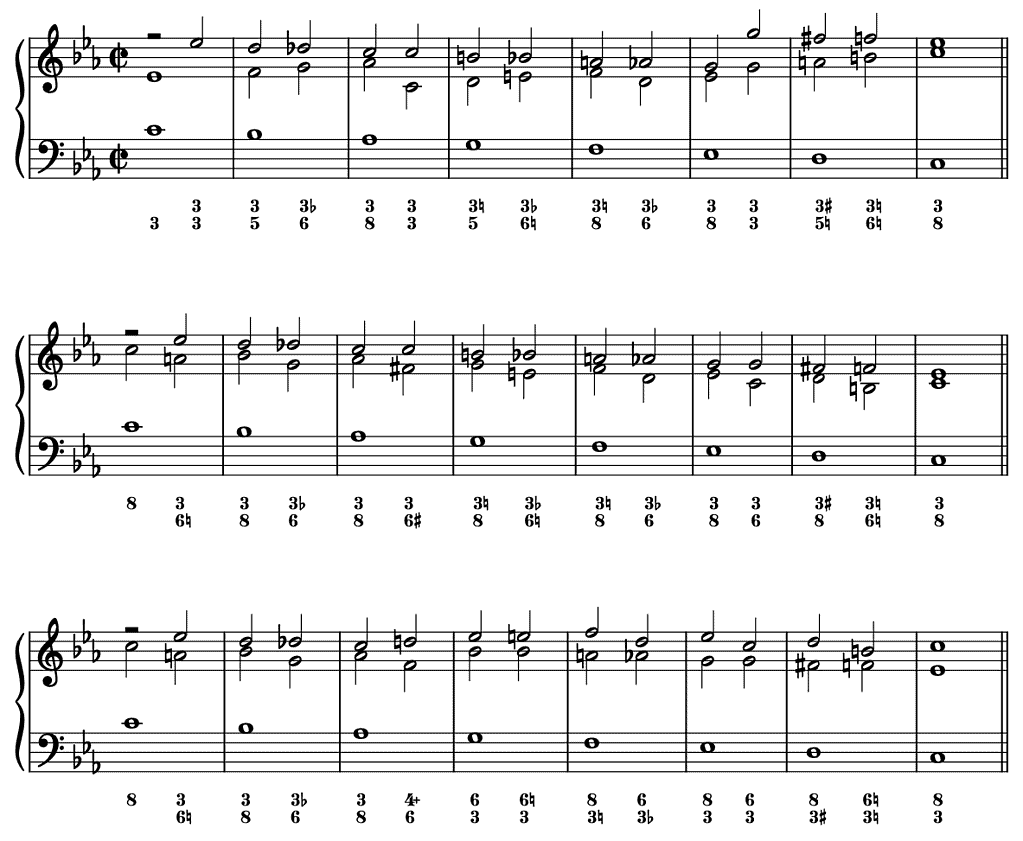

In my essay Diatonic Moti del Basso that Rise Stepwise, I illustrate how an ascending scale ‘with doubled note values’ can be set with a chain of 7–6 suspensions provided each resolution is followed by an ascending leap of a third on the same bass note to prepare the next seventh. When a bass ‘with doubled note values’ descends stepwise, a chain of 7–6 suspensions is the most obvious setting of this bass regarding voice leading. One upper voice progresses in parallel thirds with the bass, the other upper voice produces the 7–6 suspensions. In this case, the resolution of each suspension –the sixth– becomes the preparation for the next seventh. In both modes, this moto can span a full octave.

5–6/4+/2–6

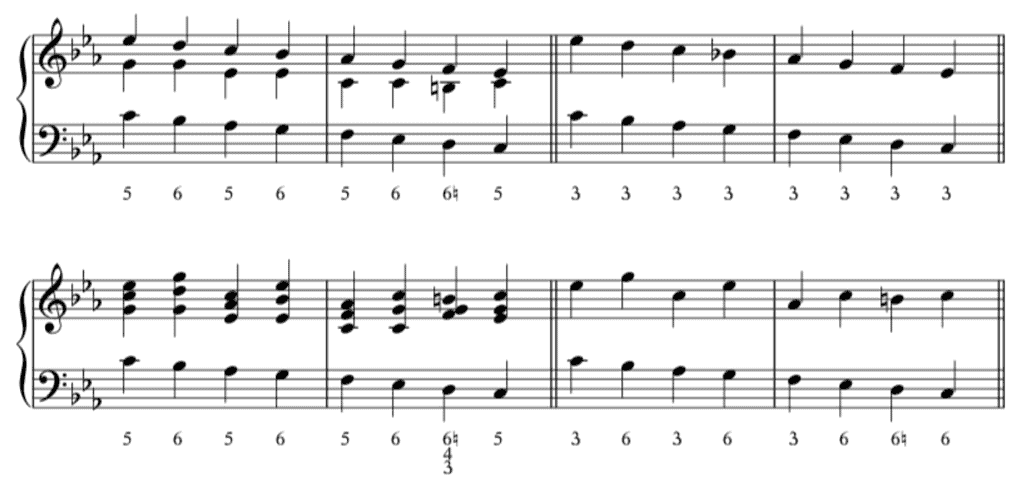

An alternative to the 7–6 pattern is the 5–6/4+/2–6 pattern, where every uneven bass note is realized by two chords, a triad followed by a 6/4+/2 chord:

Note that

- this moto is an elaboration of the Stepwise Romanesca

- Vasili Byros labels this variant an inverted Fonte-Romanesca (2017: 85)

- every segment of the sequence can be seen and heard as a local ④–③ progression (in other words, bar 1 can be heard in D major, bar 2 in B minor and bar 3 in G major)

- every even bass note, although also lasting longer than one beat, is still realized by only one (sixth) chord

- the melodic augmented second in the upper voice of the second segment is not an issue

- this pattern typically occurs in major.

Q&A Moment

What is a Fonte-Romanesca? A Fonte-Romanesca is a schema that typically consists of two or three consecutive ➅–➆–➀ cadences (or Long Commas), with each subsequent cadence being a third lower than the previous one. (For more information on this schema see my essay The Leaping Romanesca: Two-Part Embellishment (Part 2) and Vasili Byros’s article Mozart’s Vintage Corelli: The Microstory of a Fonte-Romanesca from 2017.)

5–6 With Chromatics

The following moti do not appear in Fenaroli’s regole or partimenti but are derived from settings proposed in the counterpoint books of two of his students, Biagio Muscogiuri (?–?) and Vincenzo Lavigna (1776–1836). They are based on a voice leading in which most bass notes are set with a triad and a sixth chord, respectively, including chromatics and scale mutations. Note the Fonte-Romanesca in the first excerpt in major and minor.

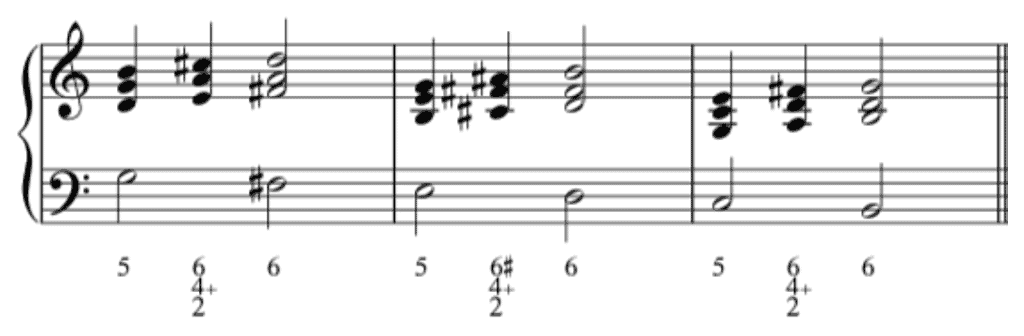

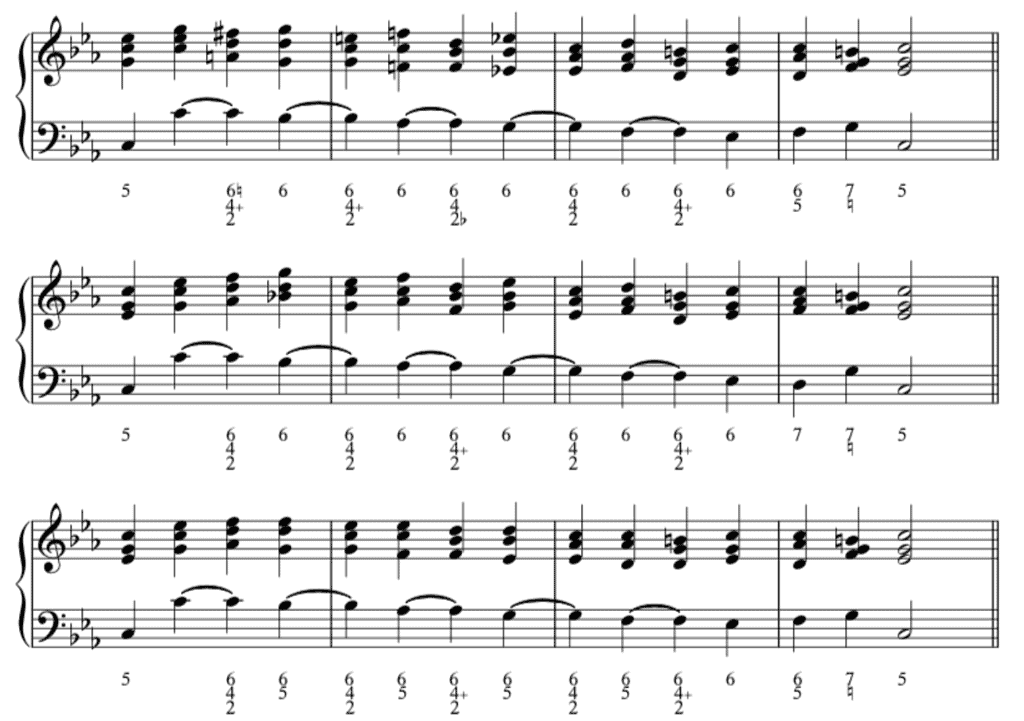

(5–)6/4+/2–6(/5) (bass suspensions)

In both major and minor, the syncopated bass of this setting can span a sixth, descending stepwise from ① to ③. Each suspension in the bass is set as a (6/)4(+)/2 sonority. These are the three common variants:

- a variant with a 6/4+/2 chord on each strong beat and a sixth chord on each weak beat, thus each time resulting in a scale mutation (note the exceptions: in C major, the snippet ⑦–⑥ is realized with a diatonic 6/4/2 and sixth chord since F sharp minor is too distant a key; in C minor, the snippet ⑤–④ is realized with a diatonic 6/4/2 and sixth chord since D minor is too distant a key)

- a variant with a (diatonic) 6/4/2 chord on each strong beat and a sixth chord on each weak beat

- a variant with a (diatonic) 6/4/2 chord on each strong beat and a 6/5 chord on each weak beat.

Whichever variant is used, when the bass has reached the syncopated ④, the rule for the suspension of this scale step demands a 6/4+/2 chord.

Further Reading (Selection)

Byros, Vasili. Mozart’s Vintage Corelli: The Microstory of a Fonte-Romanesca, in: Intégral 31 (2017), 63–89.

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).