While mastering the first four categories of the regole (cadences, the rule of the octave (RO), suspensions and modulations) was already equivalent to mastering a considerable part of the musical syntax, the assimilation of the moti del basso (or movimenti del basso) proved highly important to the eighteenth-century composer from a structural perspective. (For more information on cadences, the RO and suspensions, see https://essaysonmusic.com/partimento/.)

Moti del basso are mostly sequential patterns, each consisting of several standardized versions. They were considered essential since they offer ready-to-use building blocks that facilitate thinking at a phraseological level when composing or improvising.

This essay is the first of a series covering all moti del basso. The order and classification of the moti in this series is based on that of Fedele Fenaroli and Giorgio Sanguinetti (2012: 135–158). All moti are realized in three parts.

Although diatonic bass patterns that rise stepwise are identical to the bass of the ascending RO from a melodic point of view, they have a different harmonic rhythm. While each note of a bass realized according to the RO normally lasts no longer than one beat, each note of a diatonic ascending moto is at least twice as long, with the result that there are always minimum two sonorities per bass note. (For alternative settings of the ascending RO with one sonority per bass note see my essay The Rule of the Octave in Three Parts.)

Another common feature of diatonic moti that rise is that the second sonority on each bass note is almost always a sixth chord.

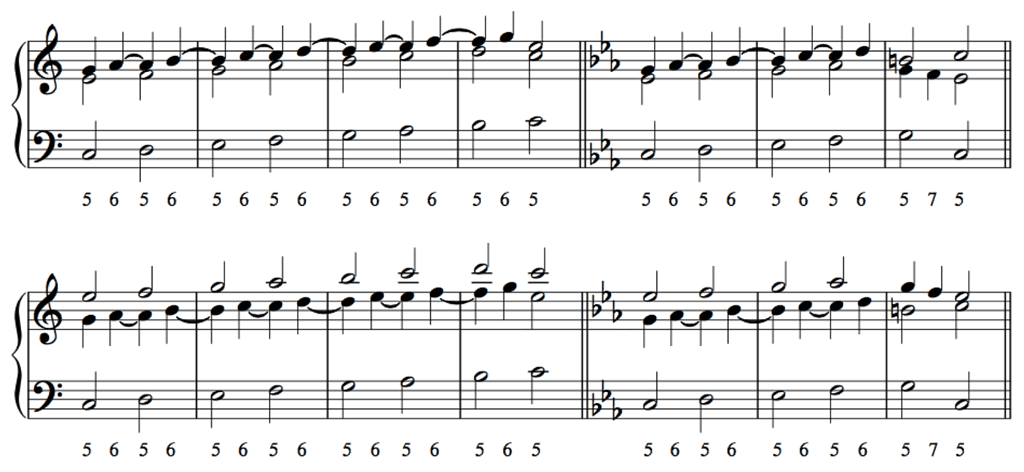

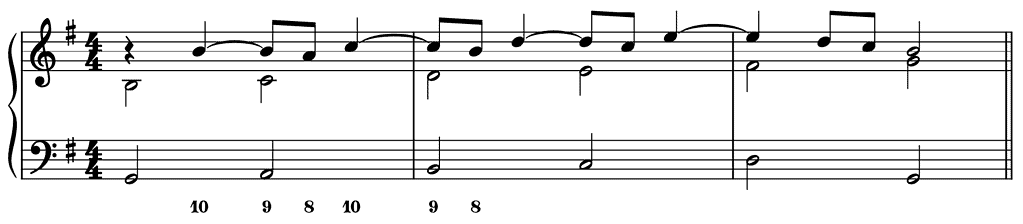

5–6

This pattern is a straightforward way to harmonize a rising scale ‘with doubled note values’. A triad and a sixth chord are played successively on each bass note, resulting in a voicing leading in parallel thirds between one upper voice and the bass. Usually, in the voice producing the 5–6 pattern, the sixth is tied to the following fifth, smoothing out the possible perception of parallel fifths. In major, this moto can stretch over a full octave; in minor, it usually breaks off after ④ (while the bass still rises to ⑤):

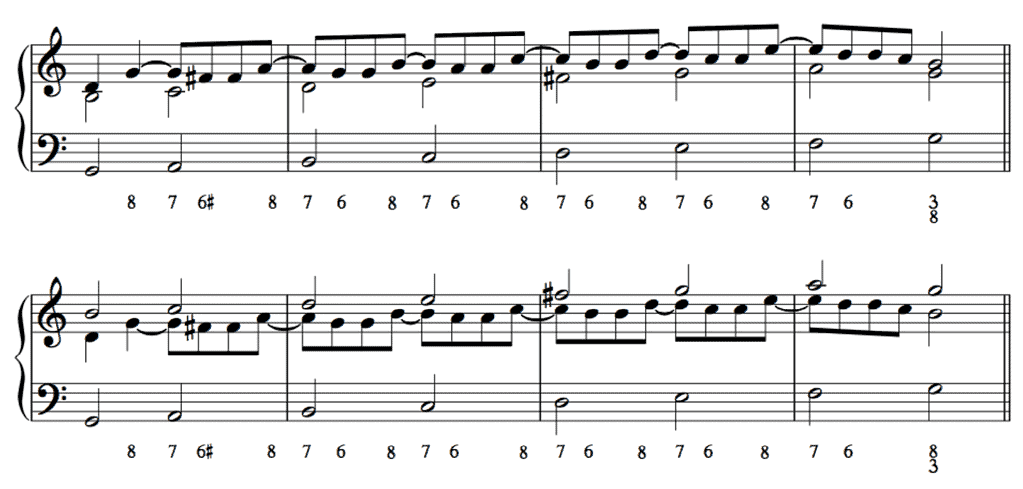

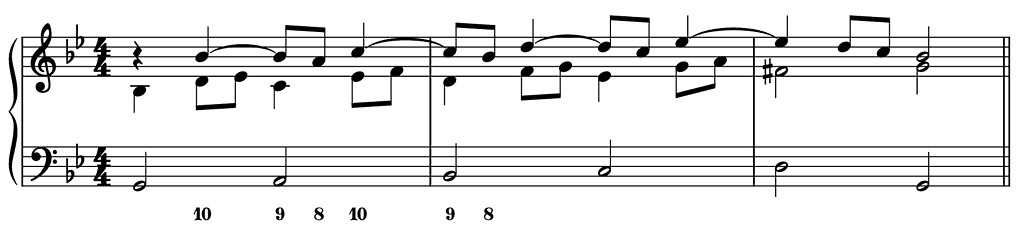

(8–)7–6

The previous moto can be enriched by replacing the 5–6 chain with 7–6 suspensions. However, since this is a rising bass, the resolution of a seventh must be followed each time by the leap of a rising third to prepare the next seventh. Again, this pattern can stretch over a full octave in major and only a fourth in minor:

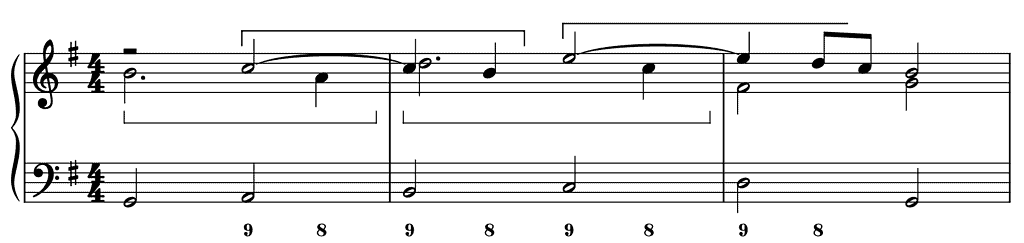

(10–)9–8

Instead of 7–6 suspensions, one can also use 9–8 suspensions to set a rising scale. While this moto exists in two positions as well, the voice leading of both is usually different. When the suspensions occur in the top voice, the voice leading is similar to that of the moto with 7–6 suspensions. Concerning the voice producing the 9–8 suspensions, the ninth is prepared by the tenth (third) and the resolution —the octave— must therefore leap up a third to prepare the next ninth. The third voice again progresses in parallel thirds with the bass.

Note that this moto breaks off as soon as ⑤ is reached. The reason is probably that continuing the pattern would result in doubling the leading note on ⑤.

In minor, at least g1 must be added in between e♭1 and f♯1 in the middle voice (bar 2b–3a) to avoid the melodic augmented second ➏–♯➐:

Note how this moto in minor briefly modulates to the relative key B flat major during the second and third bass notes.

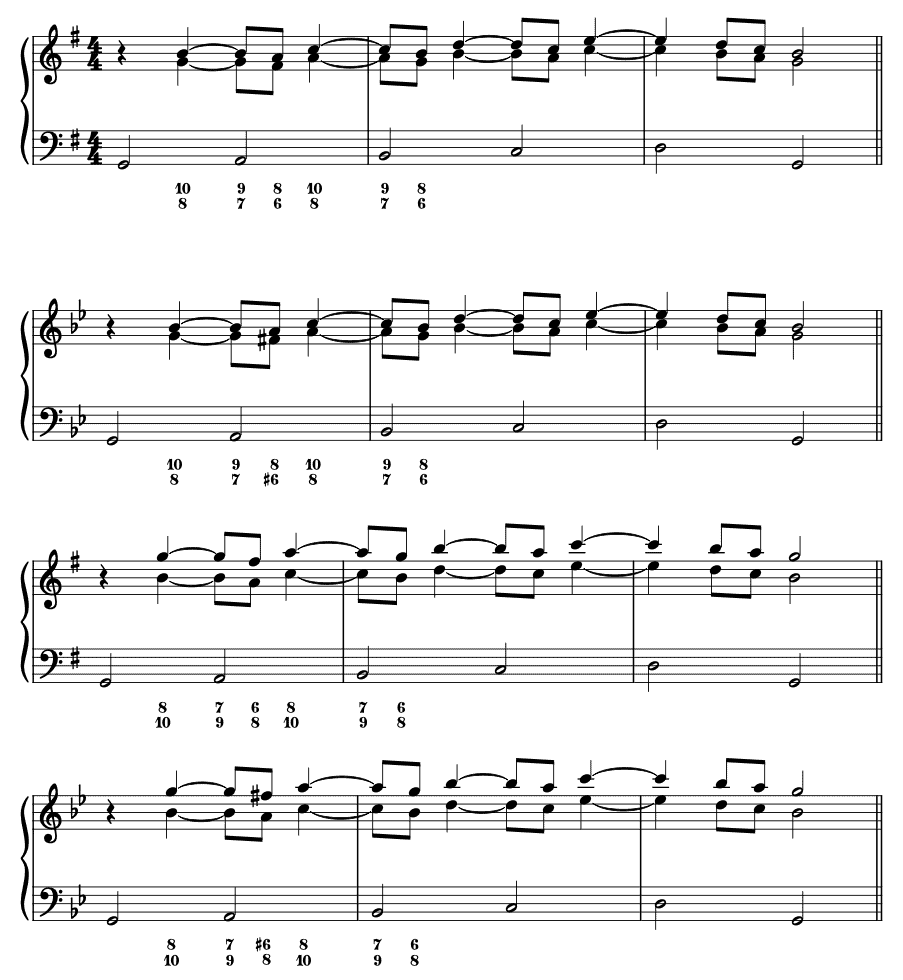

(10–)9–8 With Leapfrog

A rising scale can also be set with 9–8 suspensions using a technique known today as (Corellian) leapfrog.

In this case, the resolution of the ninth —the octave— doesn’t leap up a third on the same bass note to prepare the next ninth but leaps up a fourth to the third on the next bass note. In other words, the upper voices alternatively produce a 9–8 suspension by leaping over each other.

Note that the middle voice doesn’t leap up to f♯2 on the downbeat of bar 3 to avoid the melodic tritone.

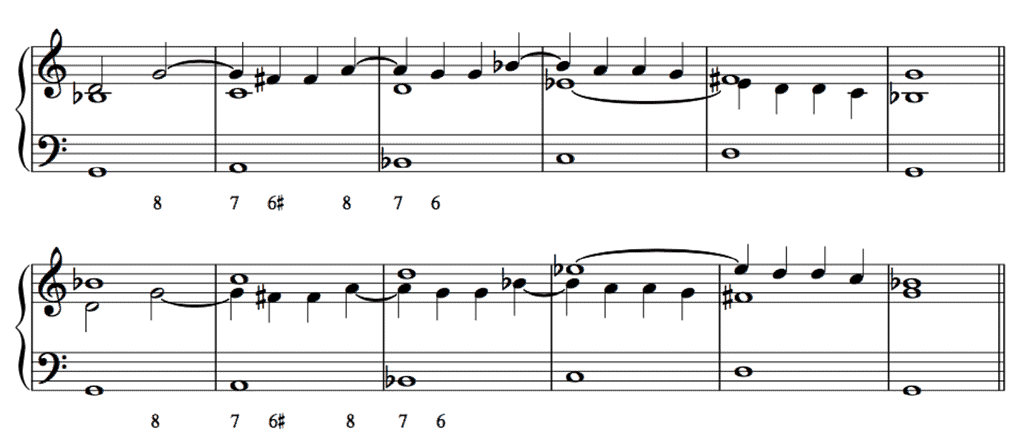

(10/8–)9/7–8/6

Both suspension chains can also occur simultaneously:

Further Reading (Selection)

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).