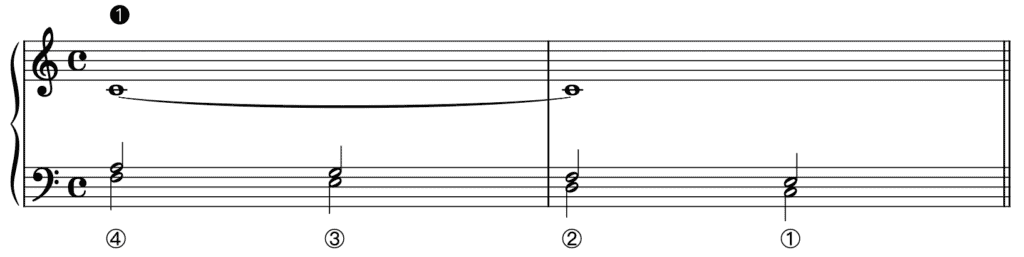

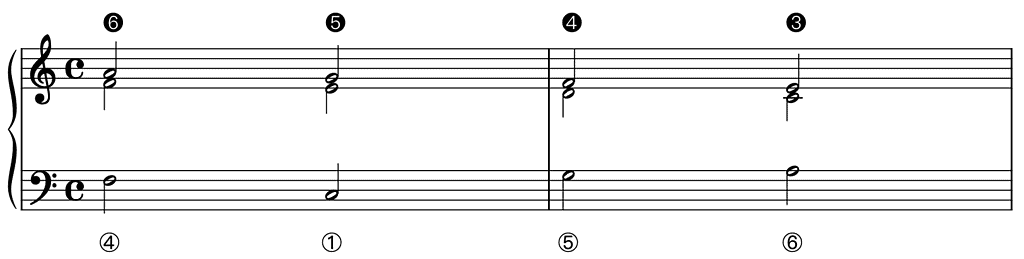

In my essay The Traditional Prinner, I explain that this schema includes a ➏–➎–➍–➌ melody above a ④–③–②–① bass.

In this essay, the first of four, I will deal with variants of the Prinner. While the ➏–➎–➍–➌ melody remains intact, it is the ④–③–②–① bass line that undergoes variation or moves up to an upper voice under a new bass.

I will therefore describe the different variants by stipulating the scale steps in the bass.

Recap: What Is a Traditional Prinner

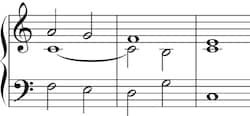

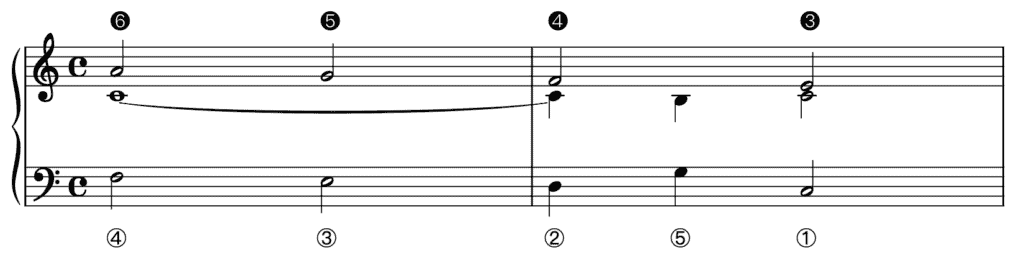

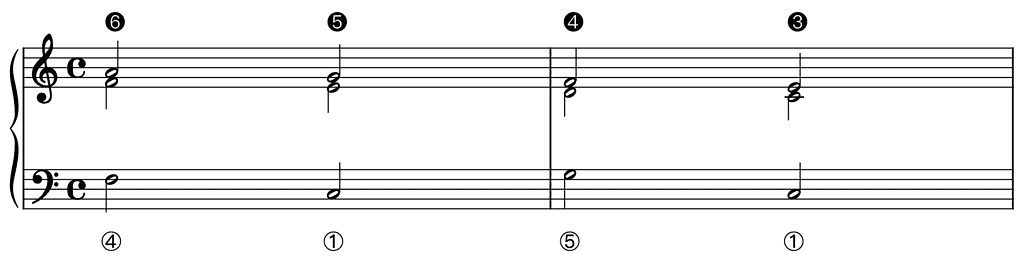

The Traditional Prinner is often used in a three-part texture and has the following characteristics:

- the bass steps down from ④ to ①

- one of the upper voices steps down from ➏ to ➌ (in parallel thirds with the bass)

- the other upper voice produces a stationary ➊ that becomes a vertical seventh above ② and resolves to ➐, forming a vertical sixth with the bass, before it rises to ➊ above ① (henceforth, the almost stationary line).

The Traditional Prinner, which functions as a mild ②–① cadence (or clausula tenorizans), appears in two versions:

- with the almost stationary line in the upper voice

- with the almost stationary line in the middle voice.

Number of Stages of a Prinner

Throughout this series on the Prinner, this schema is considered consisting of four stages, each of which coincides with one skeletal note of the ➏–➎–➍–➌ melodic progression. In case of the Traditional Prinner, the third stage —including a 7–6 suspension— is often twice as long as stages 1 and 2.

The Top Voice of the “18th-century Prinner”

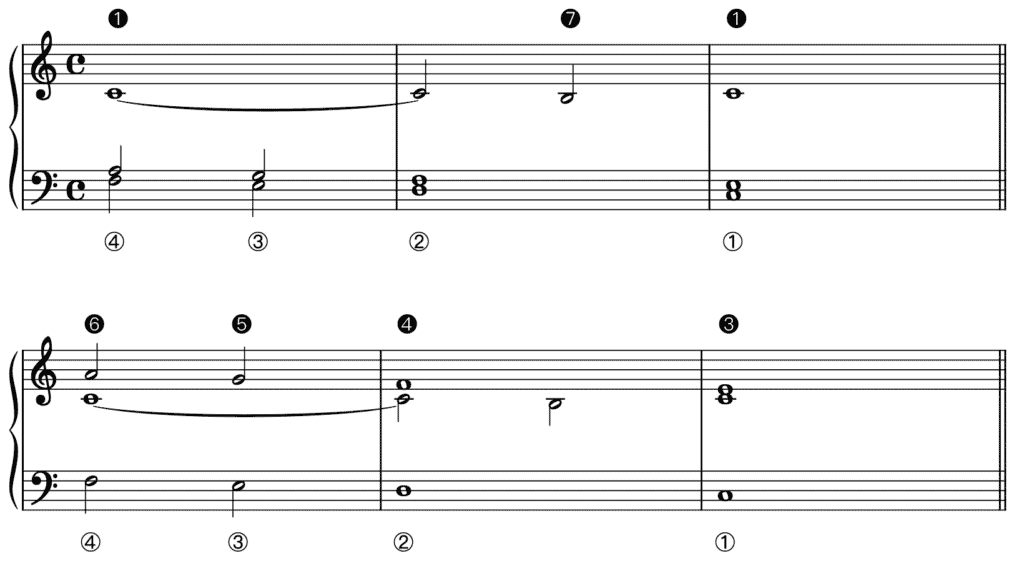

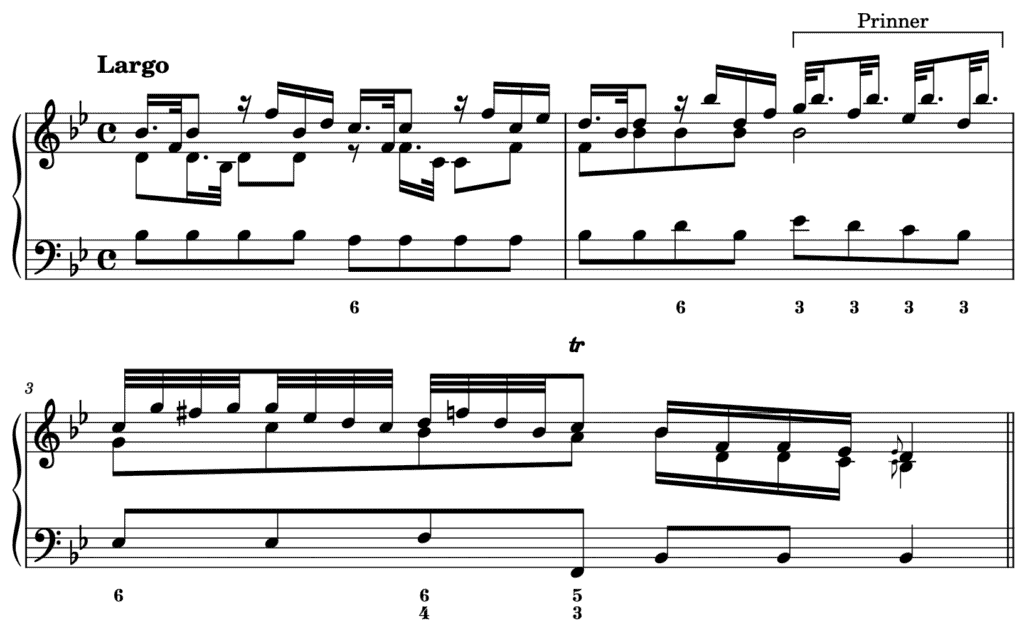

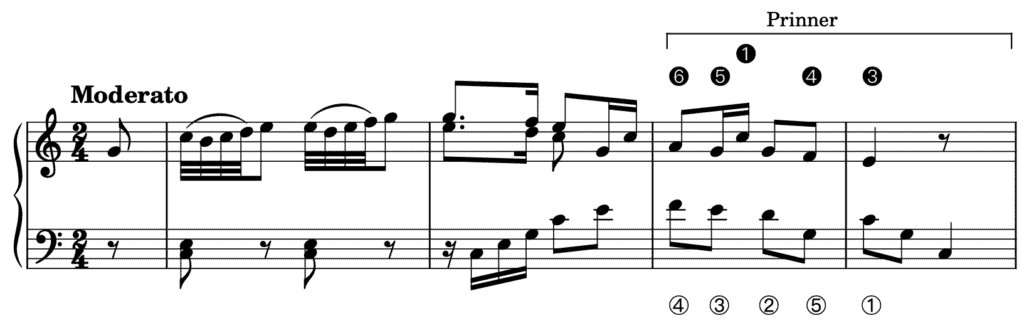

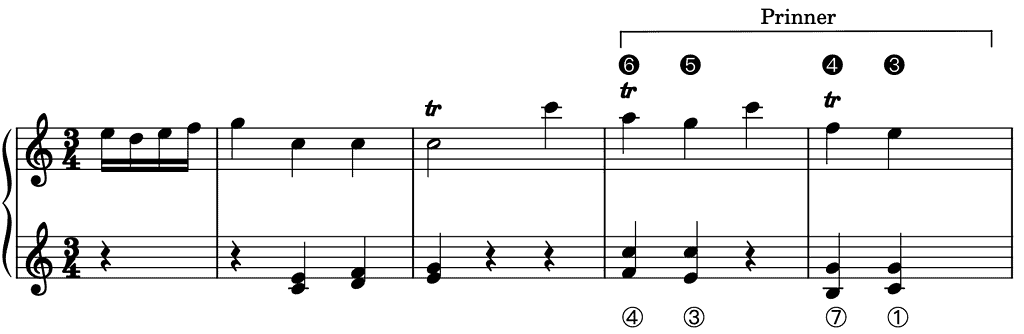

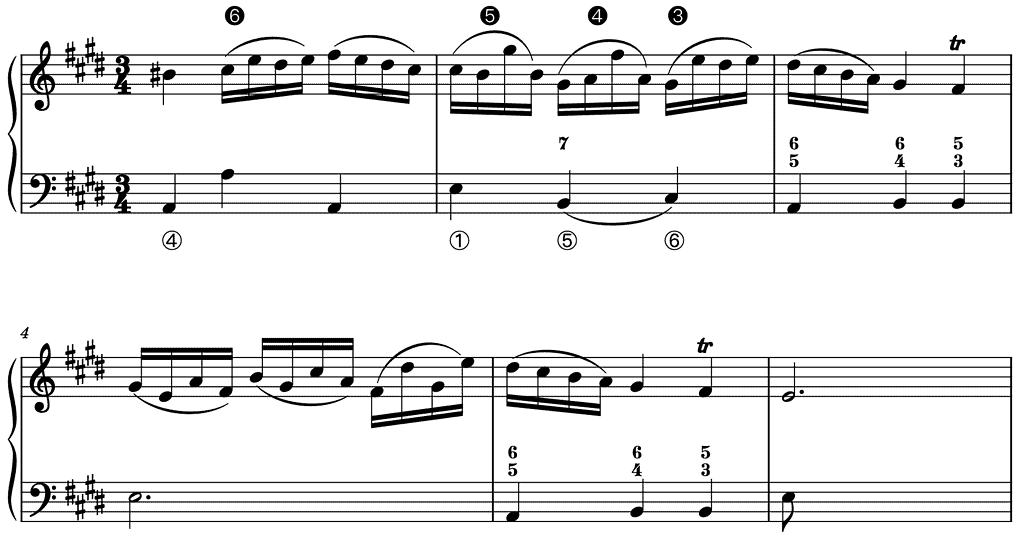

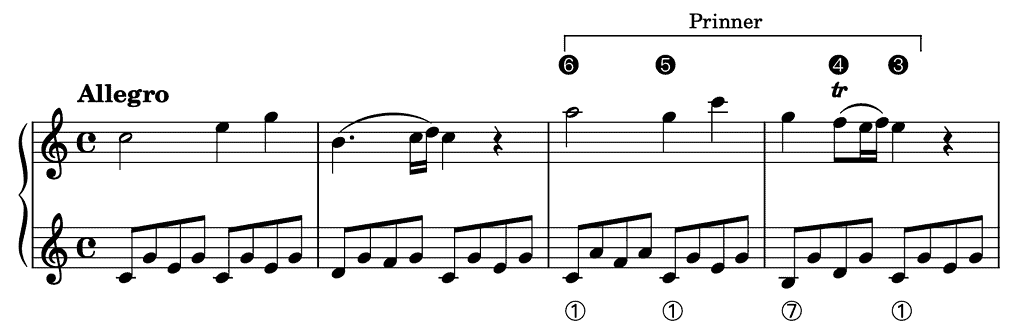

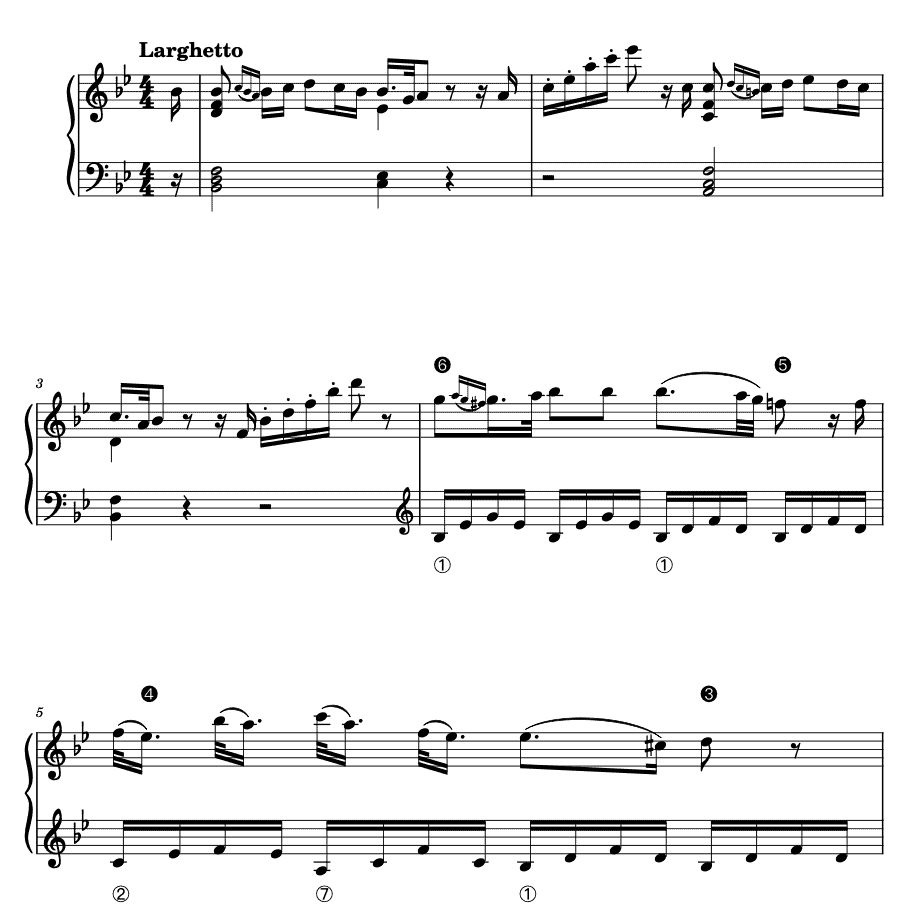

As the examples in this essay illustrate, it would appear that 18th-century composers favoured to highlight melodically the line that produces parallel thirds with the bass. Have a look for instance at the example below.

The opening gesture is followed by a Traditional Prinner that focusses on parallel thirds between the outer voices. Notice the following things about this Prinner:

- Stage 1 starts on the eighth-note upbeat to bar 3, while stages 2 and 3 each last a quarter note (bar 3).

- To make this Prinner eloquent, Haydn decided on embellishing the second, third and fourth skeletal note of the ➏–➎–➍–➌ line with an appoggiatura.

- The seventh sixteenth note in the right hand in bar 3 acts as a High ➋ Drop. (For more information on the High ➋ Drop see also my essay The Traditional Prinner.)

The Prinner Without the 7–6 Suspension

In my essay The Traditional Prinner, I deal with a slightly simpler type of Prinner whose third stage contains only a sixth chord instead of a 7–6 suspension. In other words, the almost stationary line does not include its moment where it becomes a vertical seventh on ②, resulting in a dissonance-free Prinner. This type of Prinner was still used in the 18th century, yet mostly while focussing in the melody on the line progressing in parallel thirds with the bass.

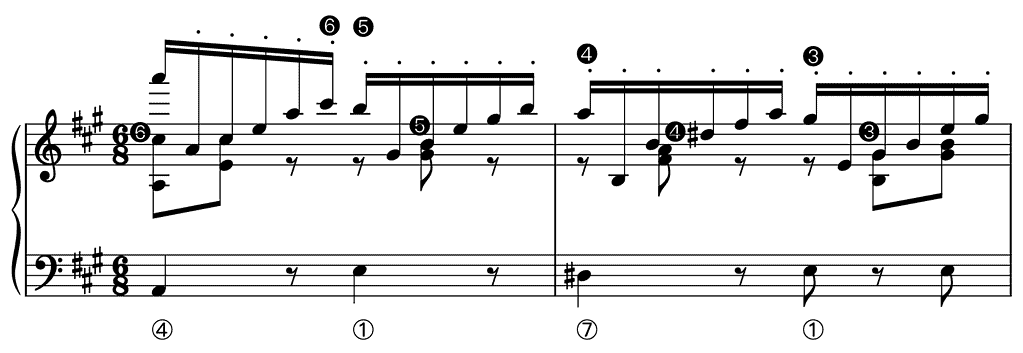

In the following example by Domenico Cimarosa (1749–1801), the opening gesture —called a Do-Re-Mi by Gjerdingen— is followed by such a Prinner. (I will deal with the Do-Re-Mi schema in a series of yet-to-published essays.) In this case, Cimarosa decided to put the ➏–➎–➍–➌ line in the top voice, as was customary in the 18th century. (Cimarosa was an Italian composer trained in Naples and one of the most celebrated composers of this time.)

The Traditional Prinner With a Stationary Line Throughout

Occasionally, while the stationary ➊ does become a vertical seventh in relation to the bass at the start of stage 3 of the Prinner, it does not resolve to ➐, the stationary ➊ just remaining stationary throughout the Prinner. As such, stage 3 —again as long as any stage— works as a ‘passing stage’ including two passing notes.

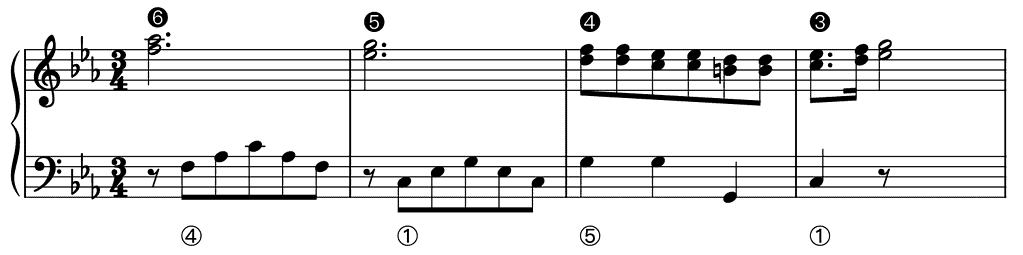

This type of Prinner was used by Fedele Fenaroli (1730–1818) for instance in the Fac ut portem of his Stabat Mater in G minor:

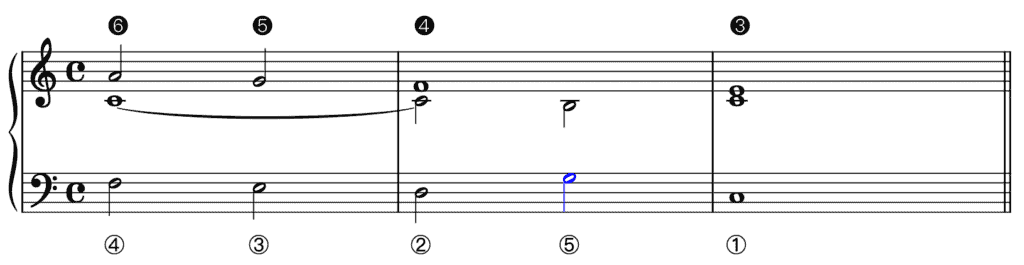

The Prinner With a ④–③–②–⑤–① Bass Line

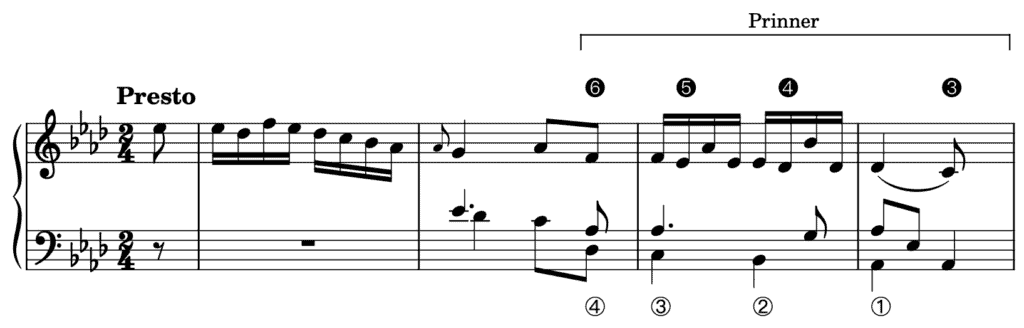

A highly popular 18th-century variant of the Traditional Prinner is the one in which ⑤ (in blue) is inserted in between ② and ①, interrupting the stepwise ④–③–②–① descent in the bass.

This added bass note makes the Prinner conclude with an authentic cadence or ⑤–① cadence instead of with a clausula tenorizans or ②–① cadence. When the ➏–➎–➍–➌ line occurs in the top voice, that ⑤–① cadence is imperfect since the soprano does not end on ➊ but on ➌. And in case there is the third, almost stationary line, the resolution of its vertical seventh with the bass does not occur on ② (as the sixth of a sixth chord) but on ⑤ (as the third of a seventh chord).

Note that in this variant, ⑤ is as long as any other stage of the Prinner. In his excellent article Harmony and Cadence in Gjerdingen’s “Prinner” from 2015, William E. Caplin refers to the added ⑤ as a “metrical extension of stage three” (Caplin: 2015, 30). There is also a variant where “⑤ appears as a submetrical insertion within that stage” (Caplin: 2015, 30). We’ll get to the latter variant below.

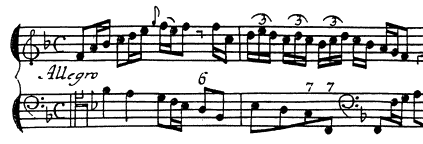

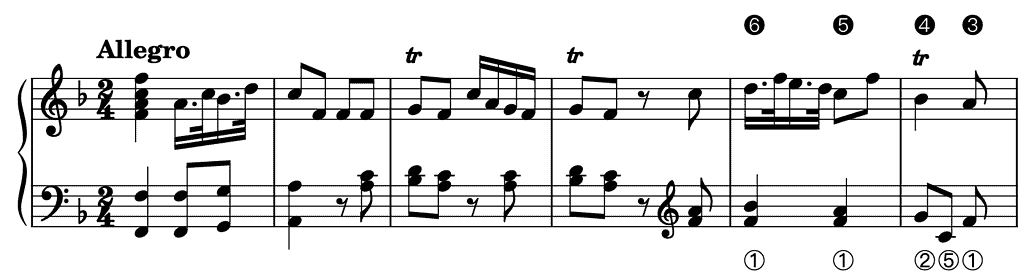

The following example, a fragment from a flute sonata by the Italian violinist and composer Pietro Antonio Locatelli (1695–1764), illustrates a Prinner in which the added ⑤ indeed results in a metrical extension of stage three. This Prinner occurs in bar 2 as risposta (answer) to the opening gesture. While the written-out music is two-part, the third, almost stationary line is implied by the continuo figures.

op. 2 No. 8/iv, Allegro, bars 1–2,

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

In this case, the opening gesture of this movement has a quarter-note harmonic rhythm, the ensuing Prinner an eighth-note harmonic rhythm, an acceleration often used in the 18th century towards the end of musical phrases. (I will deal with the opening gesture of this movement, the Galant Romanesca, in another essay.)

Another example of this type of Prinner, this time in two parts, can be seen here:

Note how Haydn touches upon the third, almost stationary line in the right hand using the technique of compound melody (For more information on compound melody see my essay The Leaping Romanesca: Two-Part Embellishment (Part 1).)

➎ Above ②

Note also that Haydn does not write ➍ but ➎ above ② in the previous example. As such, ➎ acts as an appoggiatura of a fourth. What is typical about this galant embellishment, is that this appoggiatura does not resolve on the same bass note ② but on ⑤, where the resolution becomes the top note of a vertical seventh.

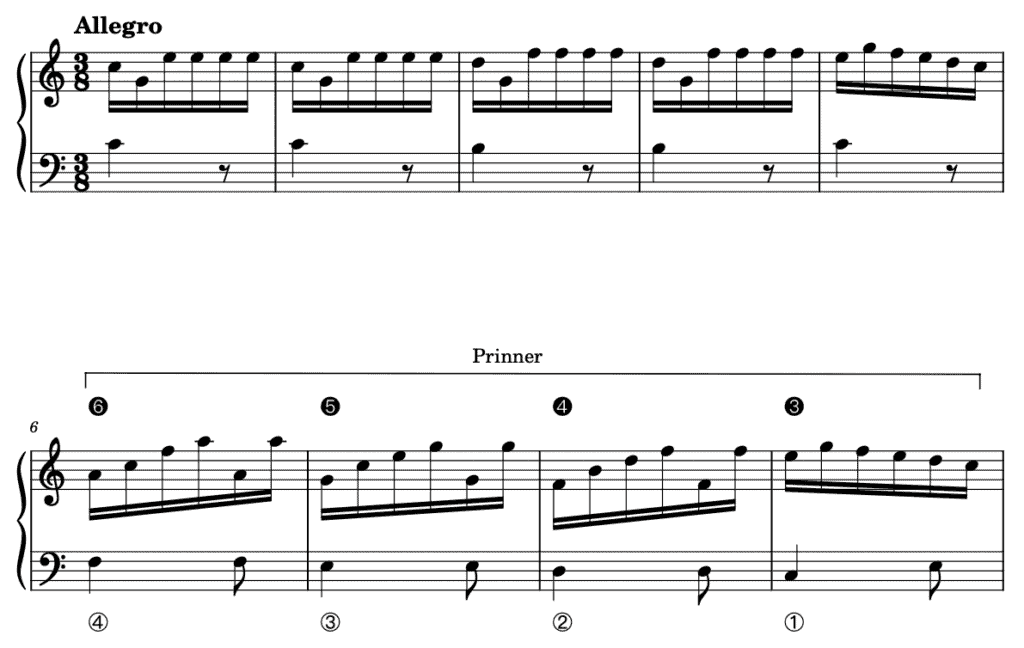

② and ⑤ Twice as Fast

As I mentioned above, composers also decided to insert ⑤ in stage 3 in between ② and ① without altering the metric regularity of the main stages. In this case, as Caplin formulates it, “⑤ appears as a submetrical insertion within that stage [three]” (Caplin: 2015, 30).

Consider the following example:

After a four-bar opening gesture installing the key of G major, Haydn again writes a two-part Prinner ending with ⑤–① as risposta. However, ⑤ appears here as a submetrical insertion instead of a metrical extension of stage 3.

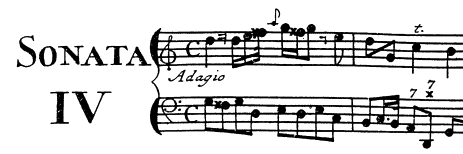

Yet another way to metrically organize the Prinner with a ④–③–②–⑤–① bass line is by having its first stage work as an upbeat. We already came across such an example (see the fragment from Haydn’s A flat major sonata Hob. XVI: 46 above). Below you find another example, by Locatelli. In both cases, the Prinner starts on the upbeat to bar 2, its first stage being twice as short as the other stages.

Adagio, bars 1–2,

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

The Prinner With a ④–③–②–⑦–① Bass Line

A composer could also opt to insert ⑦ instead of ⑤ in between ② and ①. As such, the Prinner concludes with a mild ⑦–① cadence (or clausula cantizans) instead of an incomplete authentic cadence. In this case, the beginning of the third stage is usually set as a sixth chord since the presence of a seventh would result in questionable voice leading .

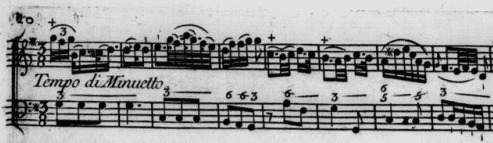

The following fragment shows the start of theTempo di Minuetto from a violin sonata by Pierre Gaviniés (1728–1800), including a rather interesting Prinner with a ④–③–②–⑦–① descent. (Gaviniés was a highly successful French violinist and composer.)

Tempo di Minuetto, bars 1–8,

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

Observe first the skeletal notes of the Prinner in bars 3 to 6, each bar constituting one stage of the schema. Focus now on the decoratio of the bass. The first stage of the Prinner (bar 3) simply reuses the motive with repeated notes of bar 1. Instead of continuing to work with this motive during each stage of the Prinner, however, Gaviniés decides to vary the decoratio stage per stage. In bar 4, he writes a ③–②–① descent, making bars 3 and 4 actually into an smaller Prinner embedded in a larger one. (During the first two stages of this smaller Prinner, the ➍–➌ snippet of the descending line walking in parallel thirds with the bass appears in the violin part, while stages 3 and 4 produce the conclusion of the almost stationary line, ➐–➊—another example of compound melody.) In bar 5, the bass starts with an eighth-note rest followed by two eighth notes A (②) and F♯ (⑦), the latter acting as a submetrical insertion during stage 3 of the larger Prinner. Due to the octave displacement in the bass and a change in decoratio in the violin part that occurs at this point, as well as to the presence of the embedded smaller Prinner in bars 3–4, the larger Prinner clearly consists of two two-bar segments. And via an octave displacement in the opposite direction in bar 6, the overall ④–③–②–① stepwise descent is complete: in this bar, Gaviniés writes a quarter note G followed by an eighth note G an octave lower.

The Prinner With a ④–③–⑦–① Bass Line

In the next variant of the Prinner, ⑦ replaces instead of ornaments ② in the bass line. Incidentally, the bass line of this variant —④–③–⑦–①— is identical to the upper voice of the voice-leading pattern that Gjerdingen calls a Fenaroli. (I will explore the Fenaroli in a series of yet-to-be-published essays.)

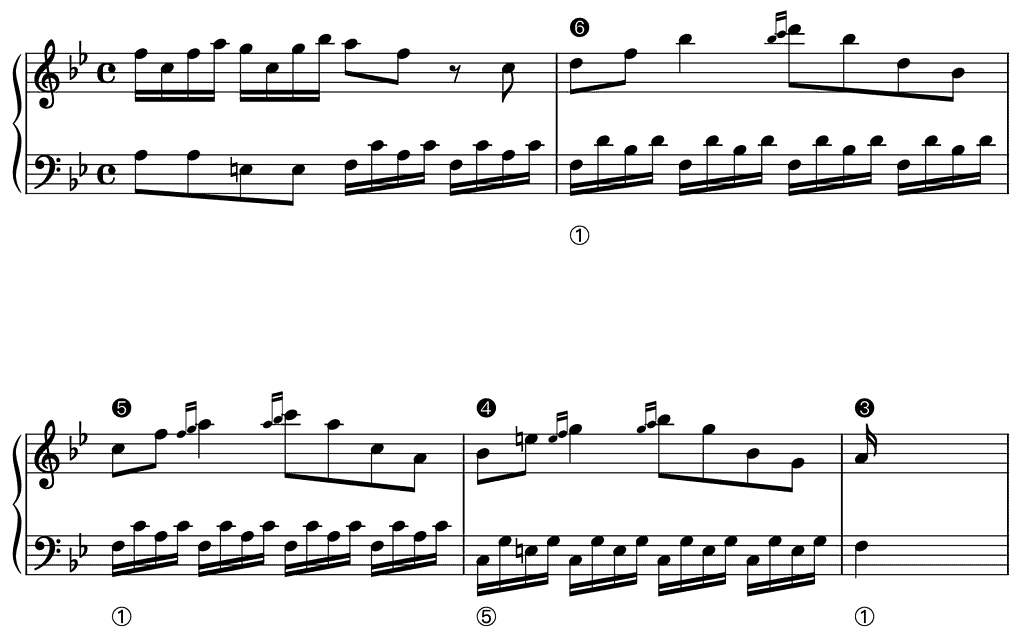

The opening gambit in the following example, which establishes the key of C major, is followed by a Prinner with a ④–③–⑦–① bass line to close off the opening four-bar phrase of this minuet’s first eight-bar half:

Below you can see and hear the beginning of an Allegro Moderato from a flute sonata by Wenceslaus Wodiczka (or Vodička; ca. 1715/1720–1774). (Wodiczka was a violinist and composer of Bohemian descent who made a career at the Munich court.)

Allegro Moderato, bars 1–4a,

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

This Allegro opens with a Galant Romanesca followed by a ③–④–⑤–⑥ cadence. Hereafter, in the first half of bar 3, Wodiczka writes a Prinner riposte with a ④–③–⑦–① bass line leading up to a half cadence —a common use of the Prinner. Note that a Prinner with a regular ④–③–②–① bass line would have worked equally well.

(Whether or not one interprets this ③–④–⑤–⑥ cadence as what Gjerdingen labels a Pulcinella depends on the continuo realization —the bass line is unfigured during that pattern. (Basically, a Pulcinella has a ③–④–⑤–⑥ or ③–④–⑤–① bass line “under an obstinate and unchanging ➊ and ➌ in the melody or inner parts (Gjerdingen, 2007: 154). I will elaborate on this type of cadence in another essay.)

The Prinner With a ③–④–⑤–① Bass Line

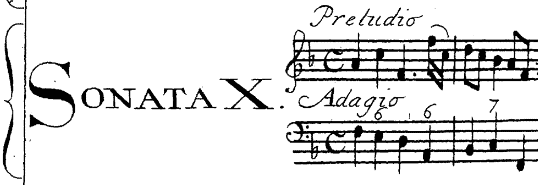

The Prinner’s ➏–➎–➍–➌ melodic descent can also be supported by a ③–④–⑤–① bass line, the bass line of “the prototypical, standard clausula in galant music” (Gjerdingen, 2007: 141). Arcangelo Corelli (1679–1752) writes such a Prinner as riposte to a Romanesca opening the prelude of the tenth violin sonata of his Opus 5:

op. 5 No. 10/i, Preludio Adagio, bars 1–2,

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

The Prinner With a ④–①–⑤–① Bass Line

Perhaps the sturdiest version of the Prinner is the one set with only triads and a dominant seventh chord. In this setting,

- the bass line produces ④–①–⑤–①

- one upper voice produces ➏–➎–➍–➌

- the other upper voice produces ➍–➌–➋–➊, that is, the descent that occurs in the bass of a Traditional Prinner.

Domenico Cimarosa (1749–1801) wrote several exemplars of this type of Prinner. The one below is an excerpt from his motet Cœli voces he wrote in 1767 as a student at the Loreto Conservatory. This example also illustrates that the Prinner occurs in a minor key as well.

(top voice: violin 1, middle voice: violin 2, bass: BC, vocal bass omitted)

The Prinner With a ④–①–⑤–⑥ Bass Line

While a Prinner with a ④–①–⑤–① bass line ends with an imperfect authentic cadence, a composer could also decide on ending the pattern with a broken cadence:

The next example shows a fragment from a violin sonata by Simon Leduc (1742–1777). (Leduc was a French violinist and composer who studied with Gaviniés.)

Amabile con grazie (in E major), bars 14–19

In this case, the Prinner with a ④–①–⑤–⑥ bass line is followed by an imperfect and a perfect authentic cadence to bring the phrase to an end.

The Prinner With a ④–①–⑦–① Bass Line

The Prinner with a ④–①–⑤–① bass line can be varied by replacing ⑤ with ⑦. As such, the Prinner concludes with mild ⑦–① cadence (or clausula cantizans) instead of an incomplete authentic cadence.

In the example below, Johann Baptist Wanhal (or Vanhal; 1739–1813) uses such a Prinner to modulate from the main key A major to E major. (Wanhal was a violinist, organist, pedagogue and composer from Czech origin who made a career in Vienna.) In mentioning its scale steps, I have looked at this Prinner from the point of view of E major. As I will elaborate on in another essay, this modulation technique was omnipresent in the 18th century.

Note how the ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent occurs in both the first and the second violin.

The Prinner With a ①–①–⑦–① Bass Line

As the following example by Mozart illustrates, one can also opt to swap the middle voice and the bass of the Traditional Prinner without 7–6 suspension. In this version, the Prinner starts with an appoggiatura six-four chord on ① (bar 3a), followed by a tonic triad on ① (its resolution; bar 3b) and a mild ⑦–① cadence or clausula cantizans (bar 4):

The Prinner With a ①–①–②–⑦–① Bass Line

A variant of the Prinner with a ①–①–⑦–① bass line is the one in which ② is added before ⑦ during stage 3. Baldassare Galuppi (1706–1785) penned such a Prinner as riposte to a schema that Gjerdingen has baptized an Aprile in a keyboard sonata in B flat major. (Galuppi was a highly successful Italian composer of, amongst others, operas and church music. I will deal with the schema Aprile in another essay.)

Note that

- from stage 3, the original bass line of the Prinner is regained (from ②)

- ⑦ appears here as a submetrical insertion.

The Prinner With a ①–①–②–⑤–① Bass Line

The former variant can in its turn be varied by replacing ⑦ with ⑤. Just as is the case in the previous variant,

- from stage 3, the original bass line of the Prinner is regained (from ②)

- ⑤ appears here as a submetrical insertion.

The Prinner With a ①–①–⑤–① Bass Line

One can also omit ② from the bass and give only ⑤ during stage 3. As such, stage 3 consists of an unprepared vertical seventh between the outer voices.

Note that in Cimarosa’s time, the minor seventh, the diminished fifth and the augmented fourth were no longer considered dissonances but “false consonances”, which explains why this type of Prinner was used then. Fedele Fenaroli (1730–1818), Cimarosa’s teacher at the Neapolitan Loreto Conservatory, explains it as follows: “The minor seventh and diminished fifth are consonances because they do not require preparation, but only resolution by descending step” (F. Fenaroli, Regole Musicali, 1795, p. 6, my translation; for more information on this matter see my article On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update from 2018).

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Fenaroli, Fedele. Regole Musicali Per li Principianti di Cembalo. Nuova Edizione Accresciuta (Naples: Domenico Sangiacomo, 1795).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Prinner, Johann Jacob. Musicalischer Schlissl (1677).

Secondary Sources

Caplin, William E. Harmony and Cadence in Gjerdingen’s “Prinner”, in: What Is a Cadence? Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, ed. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015), 17–57.

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207-229.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).