In this essay, I will illustrate how one can transform a schematic version of the Leaping Romanesca —also called the Pachelbel Bass or Pachelbel sequence— into two-part settings with embellishments. My elaborations are inspired by German and Italian 18th-century repertoire and pedagogical sources.

Embellishments form an essential part of composition and improvisation. Thanks to, amongst others, neighbour notes, passing notes, escape notes and compound line, a Leaping Romanesca can be transformed from a consonant skeletal version into a meaningful and eloquent musical phrase in two parts.

Organized per type of embellishment, this essay proposes two-part ornamental settings of the schematic Leaping Romanesca set with only consonances. I focus here exclusively on embellishing the upper voice starting on ❸ with note values that are twice and four times as small as the skeletal notes. To rephrase, while the skeletal notes of the schema are half notes, the notes used to embellish them are quarter and eighth notes (or rests of those note values). Note that exhaustiveness is not the goal here; I rather want to illustrate some elementary embellishment techniques. This essay also includes definitions of the different embellishments. Musical examples can be viewed as well as listened to. However, to stimulate assimilation, I have refrained from giving complete versions of the embellished schemata. Musical examples include embellishments only for the first segment, leaving the completion to you.

Recap: What Is a Leaping Romanesca?

Below you find the Leaping Romanesca as exemplified by bars 5–6a of the Canon in D major written by the German composer, organist and pedagogue Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706). For more information, see my essay The Leaping Romanesca (The Pachelbel Pattern): The Basics.

Embellishing Schemata

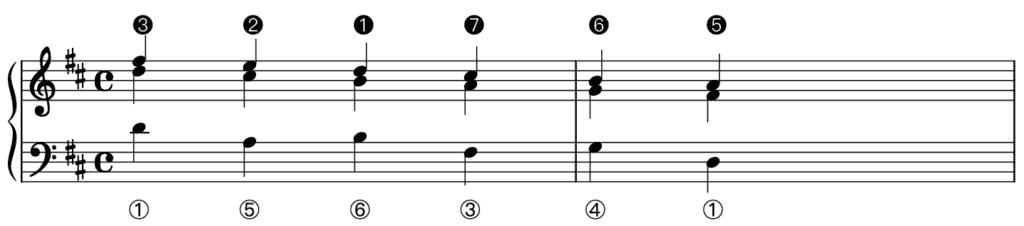

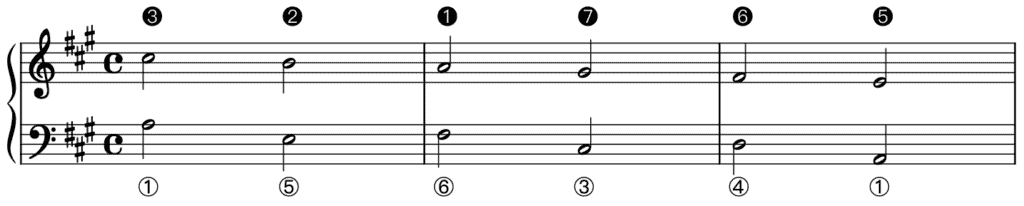

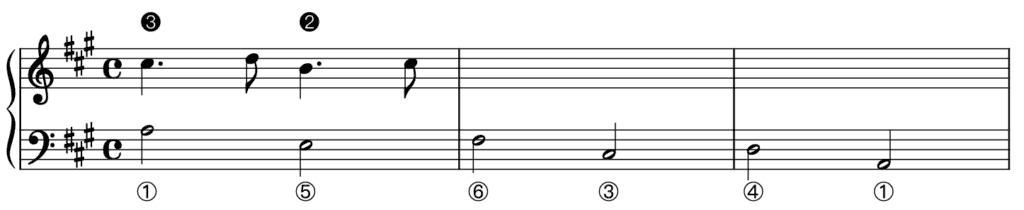

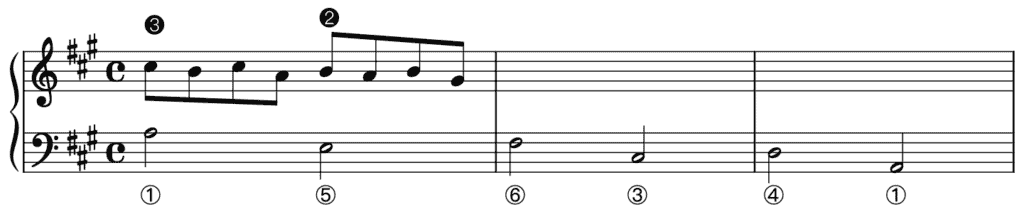

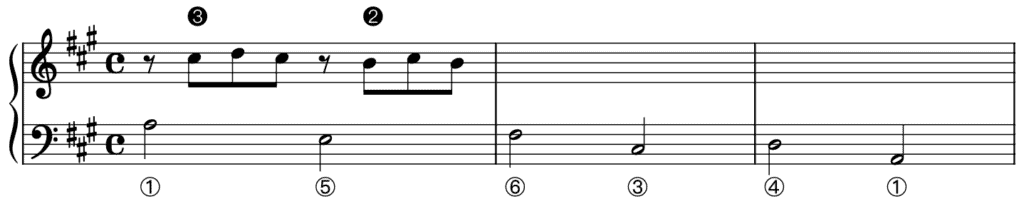

Composers obviously did not content themselves with simply reproducing patterns in its most simple, schematic version. Where would the personal statement, engagement and eloquence be? Indeed, a pattern usually featured diminutions —the term often used for several smaller note values replacing skeletal notes. The example below shows the skeletal, two-part version of the Leaping Romanesca with an upper voice starting on ❸ after Fenaroli’s partimento in A major (book 3).

With Repeated Notes

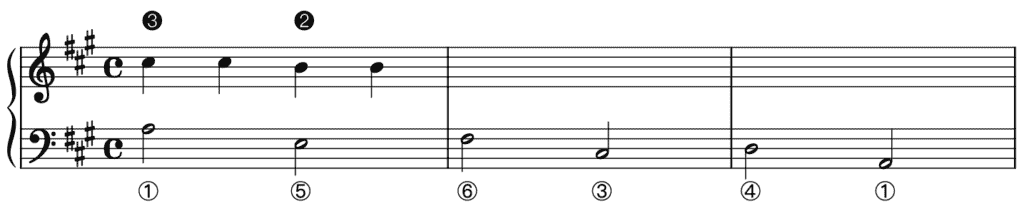

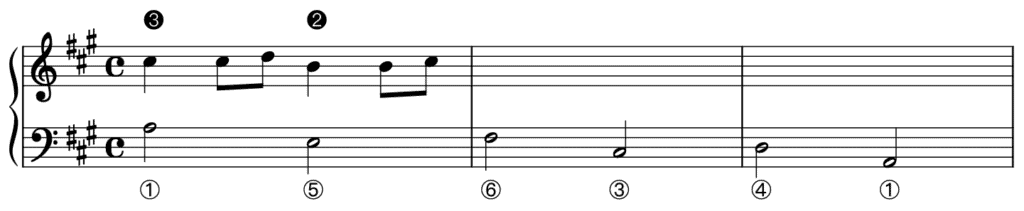

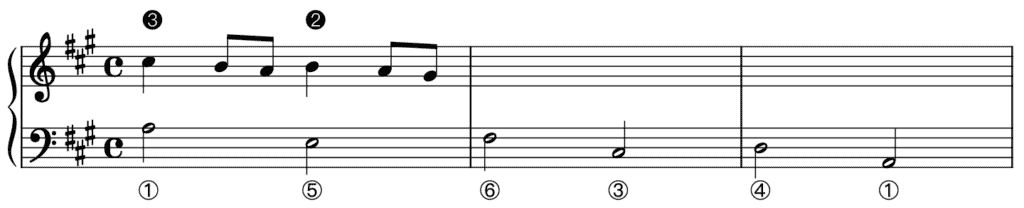

The easiest way of embellishing is by replacing skeletal notes by repeated smaller note values. In the example below, for instance, I have changed every half note of the upper voice into two repeated quarter notes:

Note that the version above uses the same diminution as the familiar song Ah! vous dirai-je, maman or Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.

The following two examples each show another variant of this technique. The first one is set with dotted rhythms in the upper voice, the second one with a motive consisting of a quarter note followed by two eighth notes.

With Escape Notes

Instead of repeating the skeletal notes, one can use escape notes.

With Repeated Notes and Escape Notes

One can combine the diminution technique of repeating notes with the one using escape notes:

With Upper Neighbour Notes

Another diminution technique to embellish the upper voice of the Leaping Romanesca is by using a neighbour-note motive. Since each subsequent skeletal note of the upper voice is one second lower than the previous one, the upper neighbour note is melodically better than the lower neighbour note.

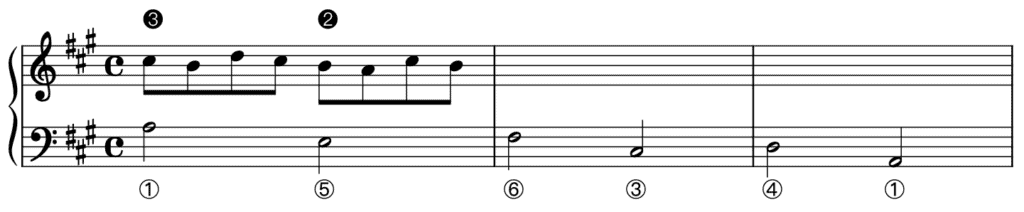

With a Double Neighbour

One can transform the variant above into a version with running eighth notes by inserting another neighbour note as second eighth note of each group of four eighth notes. As such, each half a bar in the upper voice contains a double-neighbour-note motive.

Note that the double neighbour is characterized by the absence of a chord note in between the two neighbour notes.

With Lower Neighbour And Escape Notes

The following diminution transforms the skeletal half notes into four eighth notes as well. The first three eighth notes are a lower-neighbour-note motive, the fourth is an escape note:

With Arpeggiation (Compound Line)

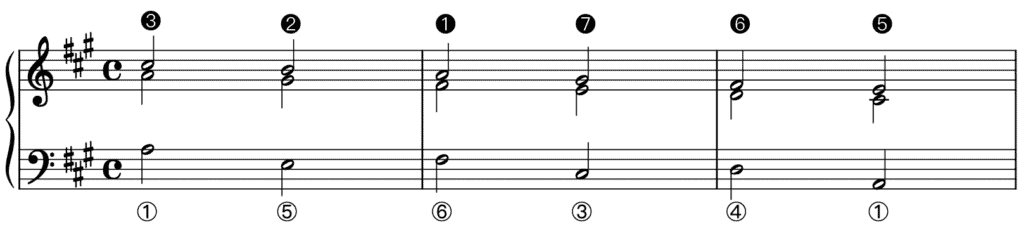

Instead of hoovering around the skeletal notes of the upper voice, one can choose to alternate between the skeletal notes of the voice starting on ❸ (on the strong beats) and those of the voice starting on ❶ (on the weak beats). As such, the figuration consists of consonant leaps. When this arpeggio technique results in an actual melodic unfolding of two or more parts, this is called compound line. The example below illustrates this technique by transforming the skeletal half notes into two quarter notes, the first one belonging to the voice starting on ❸, the second one belonging to the voice starting on ❶:

The example below renders the implicit three-part texture of the example above explicit:

With Neighbour Notes and Arpeggiation

Reconsider the variant in running eighth notes with lower-neighbour-note motives and escape notes. An alternative of this variant emerges when one replaces the escape notes with consonant descending leaps of a third:

With Passing Notes

One can also opt to elaborate this skeletal version of the Leaping Romanesca by using passing-note motives.

In the example below, motives consisting of a quarter note followed by two eighth notes are used including passing notes. Note that this variant is actually a variant of the one using the arpeggio technique/compound line. Instead of leaping down a third within each half a bar, the upper voice steps down a third via a passing note on the second and fourth beats.

The passing note can also occur on the weak part of the first and third beats. This implies that each half a bar in the upper voice consists of two eighth notes followed by a quarter note.

With Passing Notes and Arpeggiation

The former example can be transformed into a version with running eighth notes by replacing the quarter notes on the second and fourth beats with two eighth notes. The first of those eighth notes is identical to the quarter note, the second eighth note reproduces the skeletal note of the voice starting on ❸ by leaping up a third:

Starting With a Rest

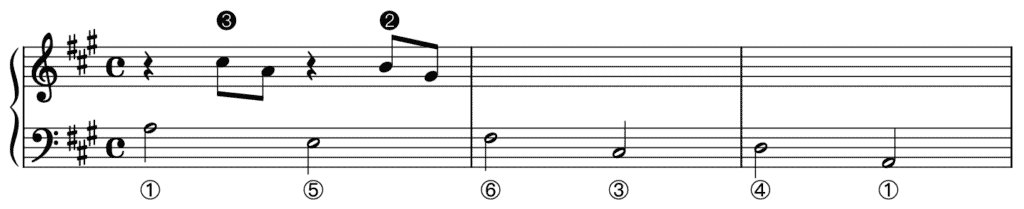

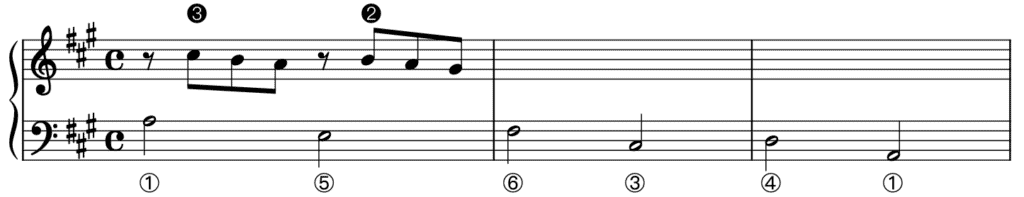

A lot of the variants I discussed above can be transformed into versions in which each stage in the upper voice starts with a rest. The usual procedure in this case is that the first note after the rest is a consonance. Below, I give only a limited number of examples.

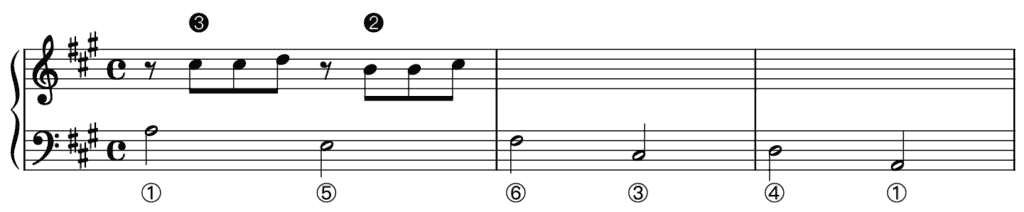

In the following example, each stage in the upper voice starts with a quarter-note rest that is followed by two eighth notes using the arpeggiation technique:

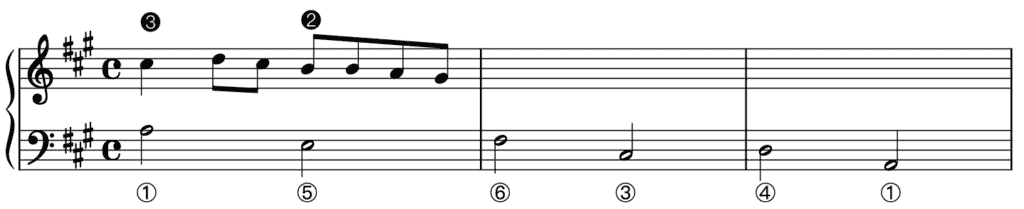

In the following example, each stage in the upper voice starts with an eighth-note rest that is followed by a passing-note motive:

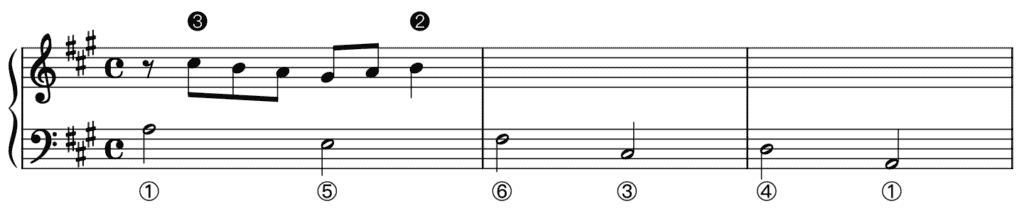

The next example is based on an upper-neighbour-note motive starting after an eight-note rest:

And in the following example, each half a bar consists of an eighth-note rest followed by two repeated eighth notes and an escape note:

Making The Segmentation More Prominent

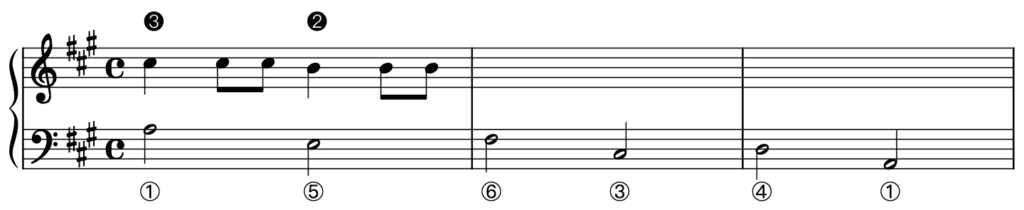

So far, all the examples of how to embellish the skeletal notes in the upper voice have been sequential per stage. In other words, I have suggested a particular embellishment for the first half note to be repeated five times. One can also opt for another embellishment for the even skeletal notes of the Leaping Romanesca. As a result, the segmentation of the pattern will be more prominent. To rephrase, embellishing the even skeletal notes of the Leaping Romanesca differently from the uneven ones will articulate each segment more than when one uses the same diminution technique for each skeletal note. Note that there is no option that is better than the other; it is simply a matter of context and taste.

The possibilities for different embellishments during the first and second stages of each segment of the Leaping Romanesca are obviously legion. Below just a couple of illustrations. I recommend analyzing the diminution techniques.

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. The Parma Manuscript — Partimento Realizations of Fedele Fenaroli (1809), ed. Ewald Demeyere (Visby: Wessmans Musikförlag,2021).

Secondary Sources

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Paraschivescu, Nicoleta. Die Partimenti Giovanni Paisiellos — Wege zu einem praxisbezogenen Verständnis (Basel: Schwabe Verlag, 2018).

Paraschivescu, Nicoleta (Translator: Chris Walton). The Partimenti of Giovanni Paisiellos — Pedagogy and Practice (New York: University of Rochester Press, 2022).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Schubert, Peter & Neidhöfer, Christoph. Baroque Counterpoint (New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006).