In this essay, I will illustrate how one can transform a schematic version of the Stepwise Romanesca into two-part settings with embellishments. My elaborations are inspired by German and Italian 18th-century repertoire and pedagogical sources.

Embellishments form an essential part of composition and improvisation. Thanks to, amongst others, escape notes, neighbour notes, passing notes and compound line, a Stepwise Romanesca can be transformed from a consonant skeletal version into a meaningful and eloquent musical gesture in two parts.

This essay proposes two-part ornamental settings of the schematic Stepwise Romanesca set with only consonances. I focus first on embellishing the melody that steps down, then on embellishing the leaping melody before including also the bass in the diminution process. (Diminutions are several smaller note values replacing skeletal notes; see also my essay The Leaping Romanesca: Two-Part Embellishment (Part 1).) In this essay, I limit myself to diminutions that are twice and four times as small as the skeletal notes. To rephrase, while the skeletal notes of the schema are half notes, the notes used to embellish them are quarter and eighth notes (or rests of those note values). For the definitions of the different embellishments, please visit my essay The Leaping Romanesca: Two-Part Embellishment (Part 1). Musical examples can be viewed as well as listened to. However, to stimulate assimilation, I have refrained from giving complete versions of the embellished schemata. Musical examples include embellishments only for the first segment, leaving the completion to you.

Recap: What Is a Stepwise Romanesca?

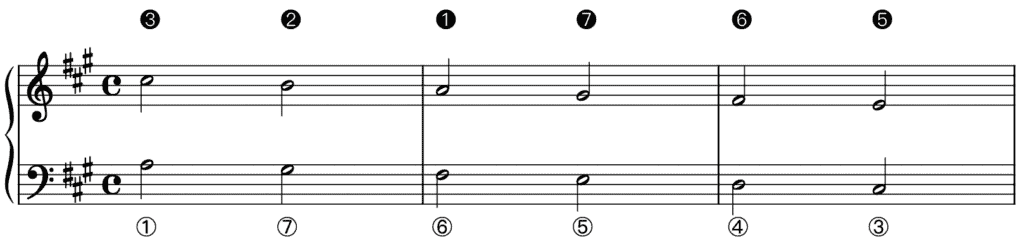

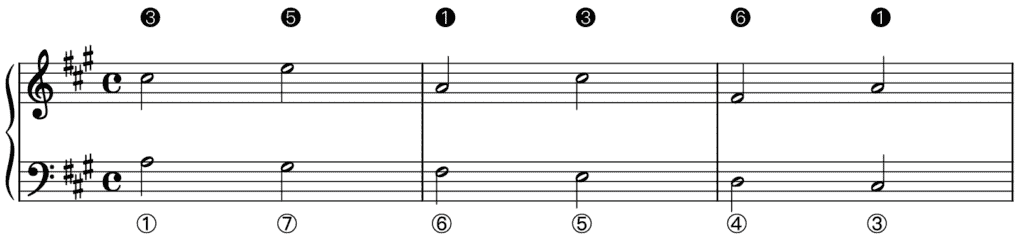

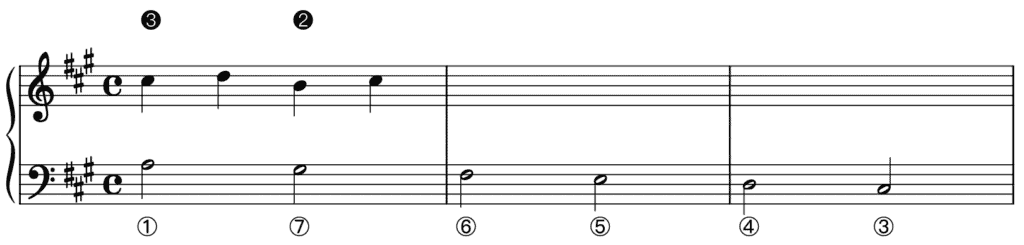

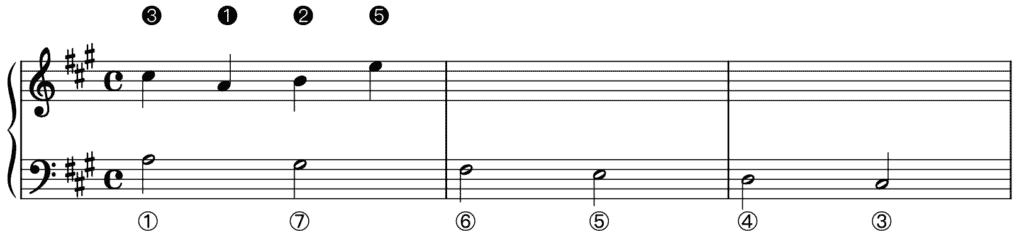

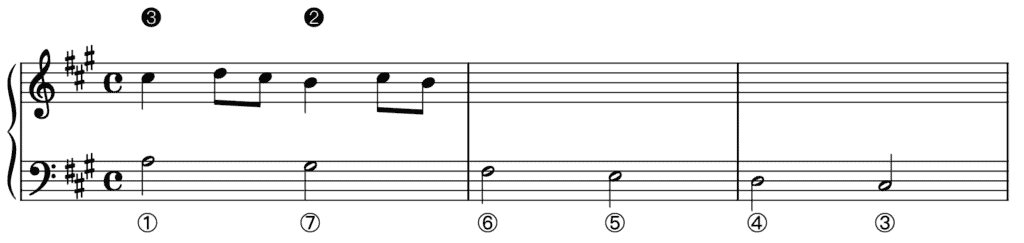

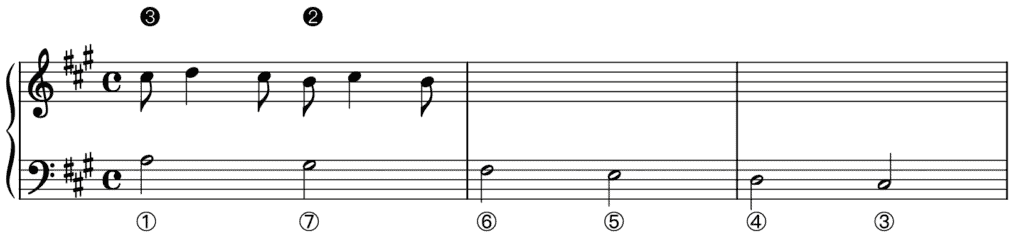

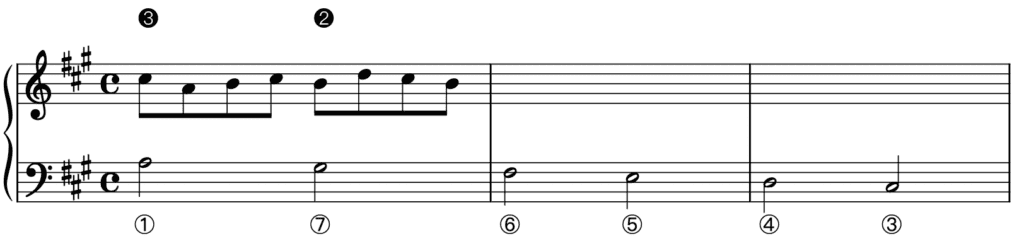

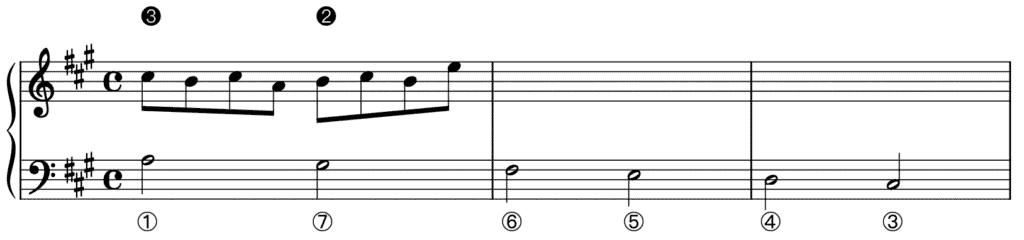

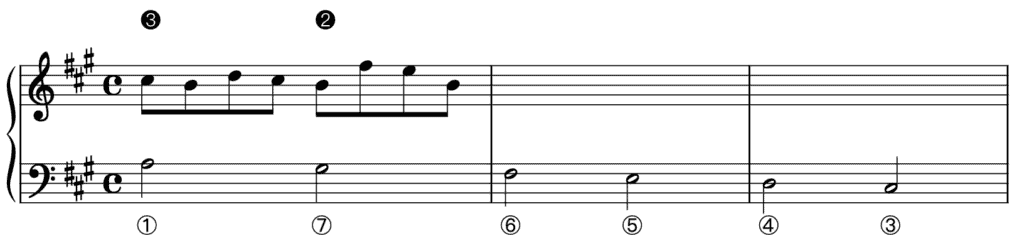

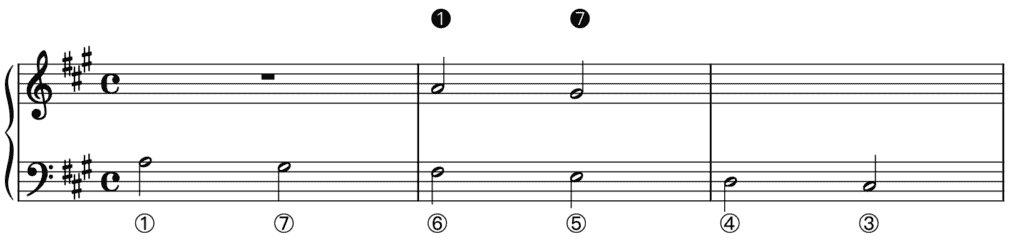

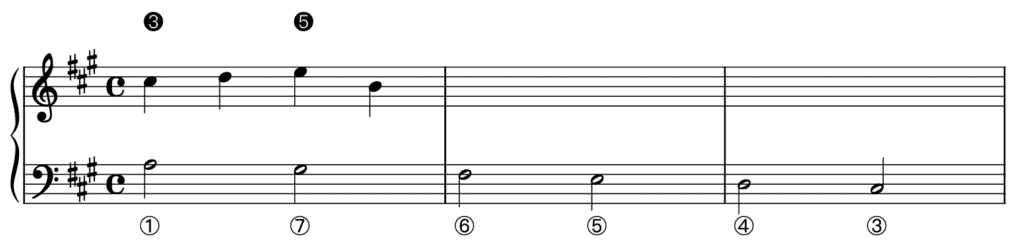

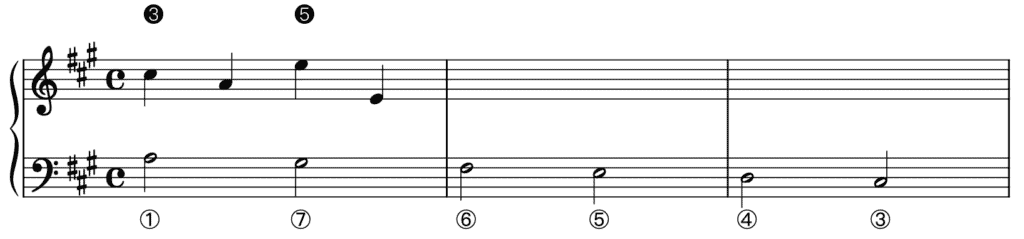

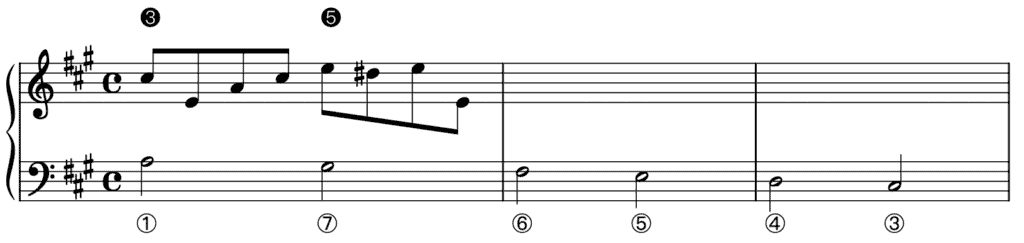

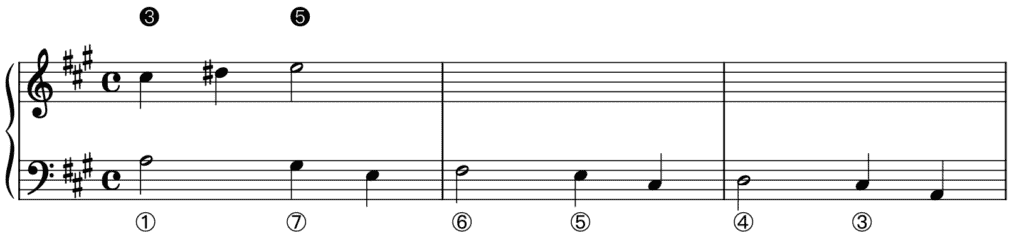

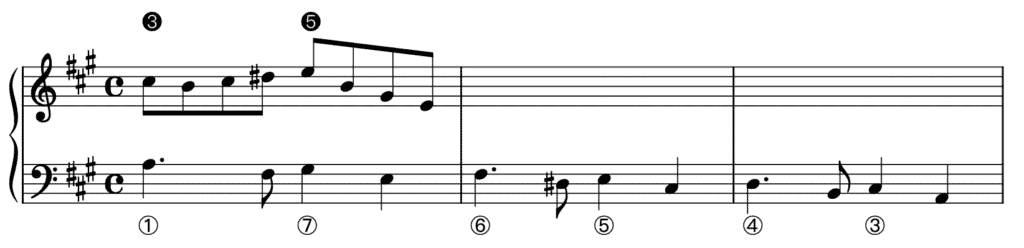

In my essay The Stepwise Romanesca: The Basics, I discuss the basic features of the Stepwise Romanesca (henceforth SR). Below you find its two first-choice two-part settings, one with a melody stepping down, the other with a leaping melody:

Embellishing The Melody That Steps Down

Let us first explore some diminutions of the melody that steps down. It goes without saying that the embellishments I give in this essay are only the tip of the iceberg.

With Quarter Notes

Important reflection first: since the melody steps down, quarter-note passing notes are not an option to embellish it.

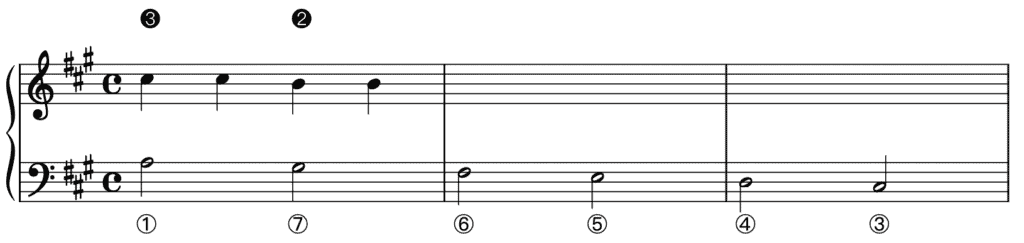

With Repeated Notes

The easiest way of embellishing is by replacing skeletal notes by repeated smaller note values. In the example below, for instance, I have changed every half note of the upper voice into two repeated quarter notes:

For other rhythms and note values with repeated notes see my essay The Leaping Romanesca: Two-Part Embellishment (Part 1).

With Escape Notes/Incomplete Neighbour Notes

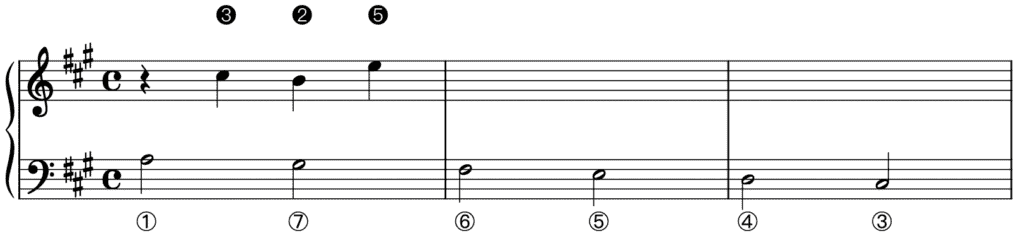

Another straightforward way to embellish the skeletal version of the SR is by using escape notes, also called incomplete neighbour notes:

With Arpeggiation/Compound Line/Consonant Leaps

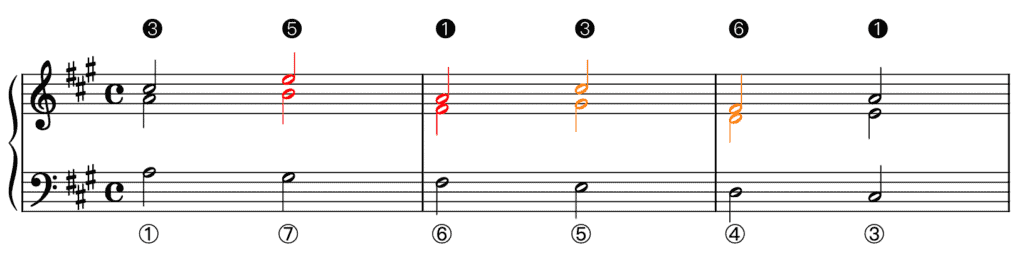

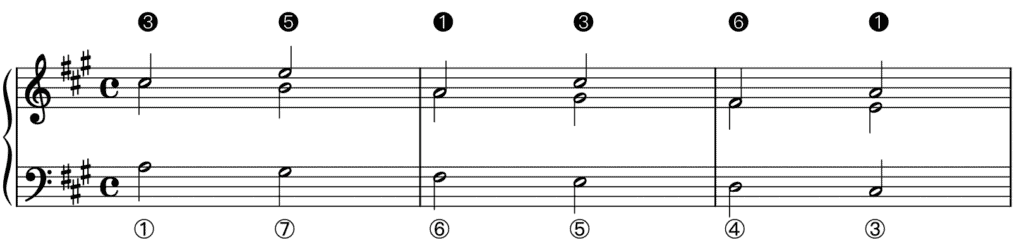

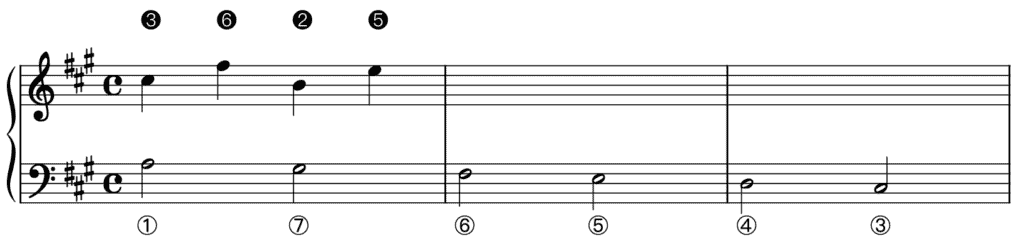

A two-part setting of the SR can be based on a three-part setting that is made implicit. This technique is called compound line, for which consonant leaps are often used. The next example illustrates this technique:

And the next example makes both implied upper voices explicit:

Note, incidentally, that this three-part example illustrates that compound line does necessarily has to depart from an impeccable setting with an extra voice. After all, the voice-leading of this three-part setting remains somewhat dubious from bar 1 to 2 and from bar 2 to 3. The three voices not only move in the same direction, the two upper voices leap down and are also involved in a voice overlap. The first voice overlap is illustrated by the red notes, the second one by the orange notes.

When the voice overlap involves one voice that steps, as is the case in the following example, this is generally considered as trouble-free:

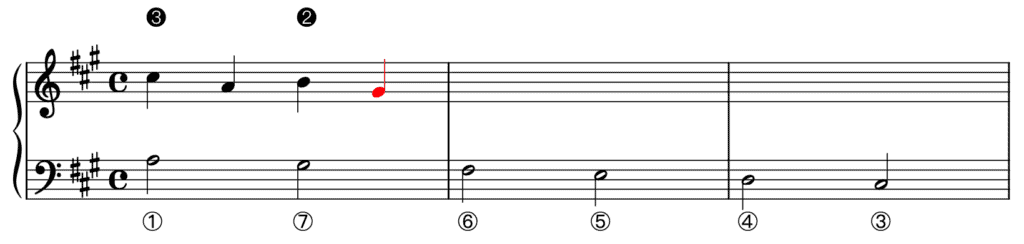

Note that one can touch upon/double the bass note during the uneven stages in the upper voice when embellishing. The reason for this is that the implied sonorities are triads. However, doubling the bass note of the even stages is not a good idea because of the implied sixth chords. Moreover, the bass note of stage 2 is the leading note, the reason why doubling it should indeed be avoided. I have produced such a dubious version below, marking the problematic note in red:

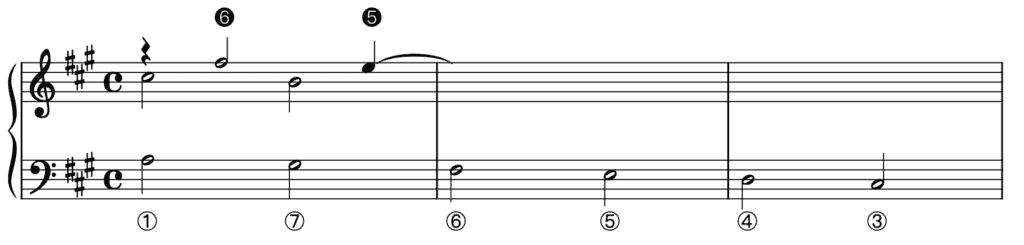

Compound line in quarter notes can also be combined with a quarter-note rest. In the following example, compound line is applied only to the even stages:

Compound line in quarter notes can also transform the SR into a related pattern. The following two examples demonstrate a 7–6 pattern in the top voice, the first example implicitly, the second explicitly:

I will deal with patterns related to the SR in more detail in a separate essay.

With Eighth Notes

With (Complete) Neighbour Notes

One can transform the version in quarter notes with escape notes or incomplete neighbour notes into complete neighbour-note motives including eighth notes. Since each subsequent skeletal note of the upper voice is one second lower than the previous one, the upper neighbour note is melodically better than the lower neighbour note:

The recurring rhythmic motive consists here of a long note followed by two shorter notes half the value of the long note. The opposite construction —two short notes followed by a long note— works equally well as a neighbour-note motive (not shown). There is also a third kind of motive consisting of a quarter note and two eighth notes, the quarter note occurring in the middle of the two eighth notes as a syncopation. The following example shows a version with this motive:

(An example of the double-neighbour-note motive in running eighth notes is given below in the paragraph With Running Eighth Notes.)

With Passing Notes

A melodic third in quarter notes going from one chord factor to another is the ideal gesture to embellish with a passing note. One can opt for a dactylus, an anapaest or for an amphibrach. The example below shows a version with the anapaest:

The passing-note motive of the example above can shifted one eighth note to the right by inserting an eighth-note rest on beat 1:

With Running Eighth Notes

Below you find three possible versions with running eighth notes:

Using Stretto

Although strictly speaking stretto is not an embellishing technique, I include it here because it is an efficient and straightforward option in making the setting eloquent. Starting at the start of segment 2, the upper voice simply reproduces the bass line:

Embellishing The Leaping Melody

Since most principles have been touched upon above, this section will be more succinct than the one discussing how to embellish the stepping melody.

With Quarter Notes

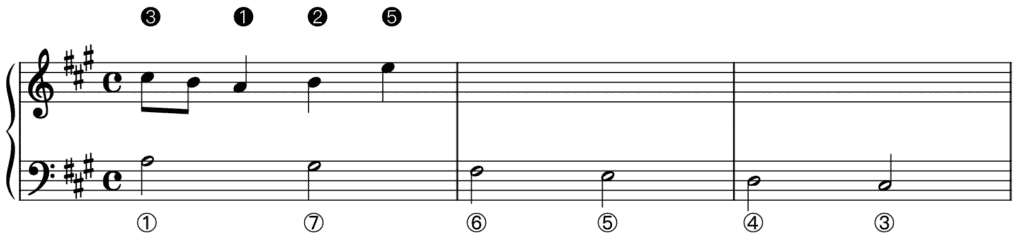

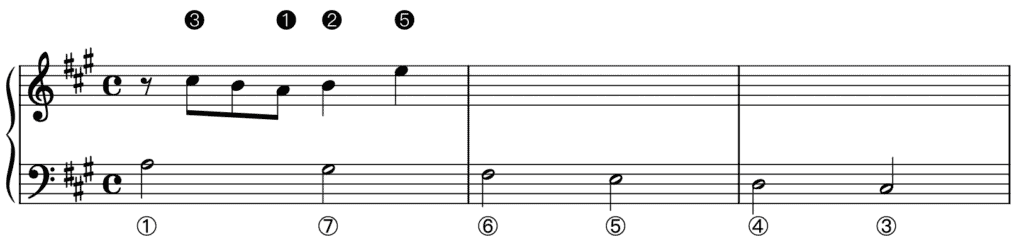

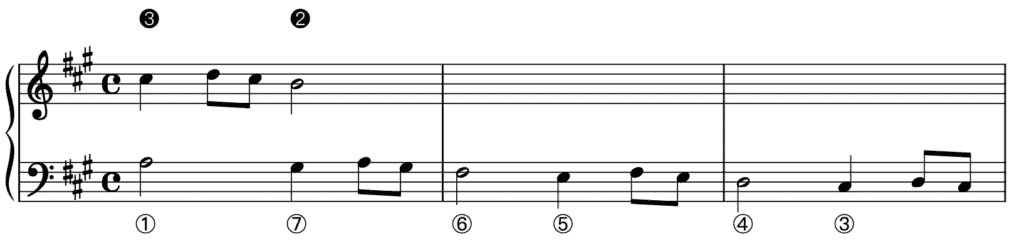

An obvious way to transform the leaping melody in half notes into quarter notes is by inserting

- a passing note in between both skeletal notes of each segment (the skeletal interval is a third and therefore perfectly suited for this type of embellishment)

- a consonant leap down a fourth in between the second note of a segment and the first note of the next segment:

One could ignore that obvious possibility to insert a passing note in between the skeletal notes of each segment and insert a consonant leap instead:

Note that I have varied the embellishment of the second skeletal note by leaping down an octave instead of a fourth.

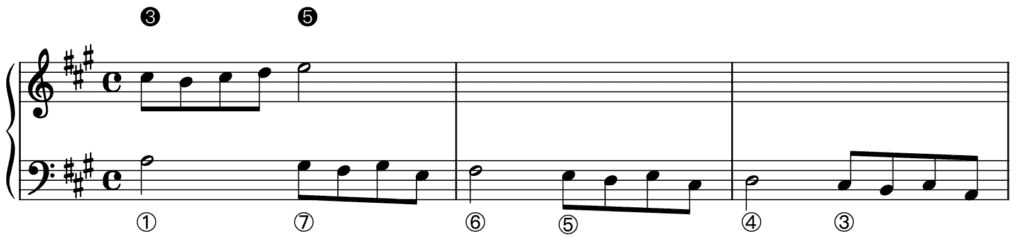

With (Running) Eighth Notes

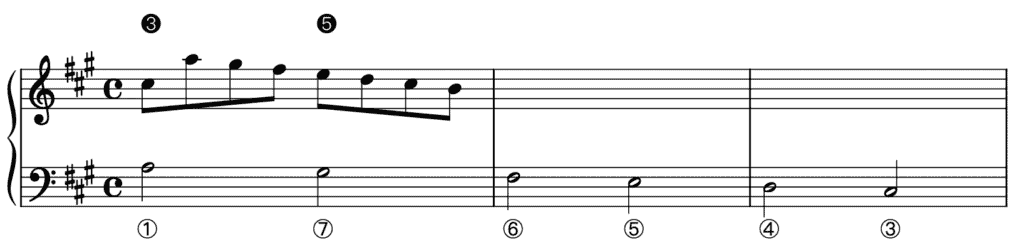

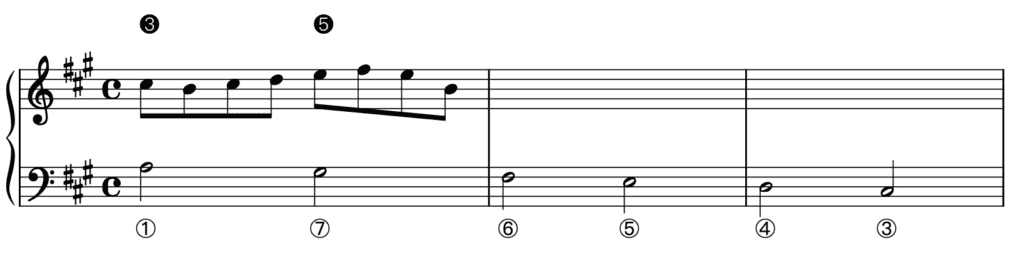

Below you find three possible versions with running eighth notes:

Embellishing Both Voices

Until now, only the upper voice has been embellished. Let us explore now some possibilities to embellish both voices.

Using Complementary Rhythm

A first way to include the bass in the embellishing process is by using what is called complementary rhythm.

Below you see an example in quarter notes and one in eighth notes:

Note that I have opted for a chromatic passing note during the uneven stages in the example above, creating (the suggestion of) a temporary shift of key. While under normal circumstances we should avoid augmented melodic intervals, in this case it is allowed to play an augmented second A–B♯ above ⑥ (Fenaroli, amongst others, defends this).

Below you see two other examples of complementary rhythm between both voices, the first using dactyls, the second a motive of 4 eighth notes:

With Freer Rhythms

Below you find just one example with freer rhythms:

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. The Parma Manuscript — Partimento Realizations of Fedele Fenaroli (1809), ed. Ewald Demeyere (Visby: Wessmans Musikförlag,2021).

Secondary Sources

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).