The Monte is a widely used schema in the 17th and 18th centuries and exists in many variants. In this essay, I will focus on the schema’s characteristics.

Just as a Fonte, a Monte is a sequential schema in which each segment constitutes a cadence, often a ⑦–① cadence or clausula cantizans as well. However, while a Fonte is a descending pattern starting in the key of the supertonic, the Monte is an ascending pattern starting in the subdominant key.

In this essay, I use upper-case Roman numerals for local major keys and lower-case Roman numerals for local minor keys.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the melody (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Term and Interpretation

The term and interpretation of the Monte (Italian for mountain) comes from Joseph Riepel (1709–1782), chapel master in Regensburg. He describes the Monte as a pattern that is often used as the opening gesture of the second half of a binary form. In other words, the Monte is an alternative pattern for the Fonte at that point in a composition. Another similarity with the Fonte is that each segment of a paradigmatic (two-part) Monte constitutes a ⑦–① cadence or clausula cantizans. Unlike a Fonte, however, a Monte

- Is an ascending sequence

- Can occur not only in major but also in minor

- Starts in IV if the main key is major, in iv if the main key is minor

- Consist of two segments in its paradigmatic form but can be expanded with one, two or even three segments.

The Two-Part Monte

The shortest type of Monte consists of two segments, like the Fonte. In a composition in a major key, both segments focus on a major key, the first on the key of IV, the second on the key of V. (While the second segment of a Fonte is written in a major key as well (I, i.e. the main key), its first segment focuses on the minor key of ii.)

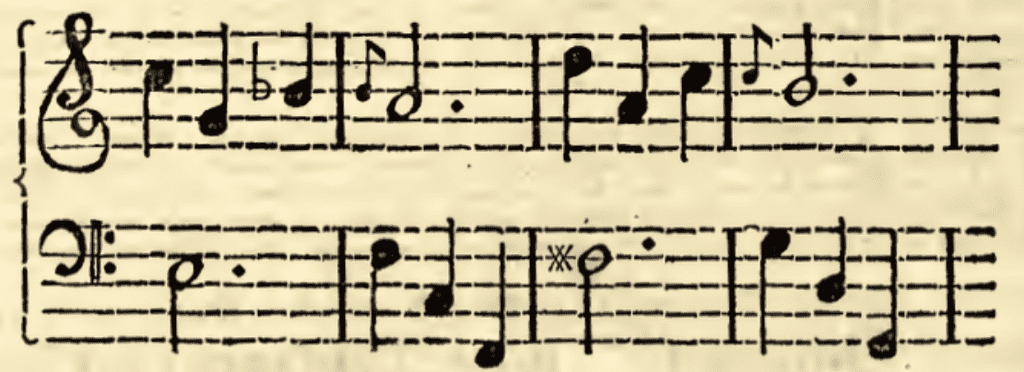

The following example from the first volume of Riepel’s Anfangsgründe (1752) shows an exemplary Monte at the beginning of the second half of a minuet in C major:

Note

- how each two-bar segment constitutes a ⑦–① cadence or clausula cantizans

- how the second segment is a transposition one step higher (in G major) of the first segment (in F major)

- that a chromatic semitone occurs in the bass between the two segments.

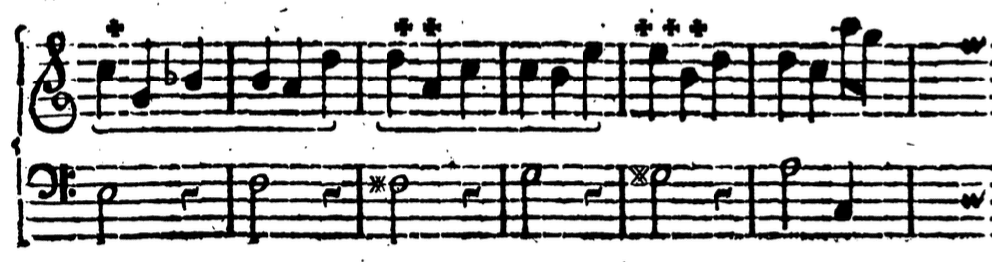

Below you can see and listen to a genuine repertory example of this type of Monte, which occurs after the double barline of a minuet in G major by the Czech violinist and composer Wenceslaus Wodiczka (ca. 1715/20–1774):

The key of this minuet being G major, the first segment of the Monte (bars 9–10) is written in the local key of C major (IV), the second segment (bars 11–12) in D major (V).

Other Types of Cadences

As with the Fonte, each segment of a Monte does not necessarily have to consist of a clausula cantizans; any cadence can be used. Since I have covered this aspect extensively when discussing the Fonte (see my essay The Fonte: The Basics), I will not elaborate on this here.

As mentioned above, unlike a Fonte, a Monte can occur in a minor key as well. (For more information on why a Fonte cannot occur in a minor key, see again my essay The Fonte: The Basics.) Consider the following example, which shows the beginning of the final movement from C.P.E. Bach’s sonata for oboe and basso continuo, a theme with variations, each written in binary form.

The key of this movement (and sonata) being G minor, the first segment of the Monte (bars 9–12) focuses on C minor (iv). As for its second segment (bars 13–16), however, it seems to start in D minor (v) yet the presence of ➐ of the main key in bar 16 (f♯2) makes it clear that this segment rather ends with a half cadence in the minor key of the tonic (i).

Note that this Monte occurs also after the double barline, which was common. Unlike the one in Wodiczka’s minuet, however, this Monte is not four but eight bars long, each segment lasting four bars. (Since the techniques to extend a Monte are the same as those to extend a Fonte, I will not discuss this further here. For more information on extending a Fonte see my essay Extending the Fonte.)

Q&A MOMENT

Can ⑤ Set as a Major Triad Descend to ④ when the Latter is Not Set with a Tritone?

(A modern way of formulating this question would probably be “Can a dominant harmony be followed by a subdominant harmony?”) Contrary to what modern textbooks generally advocate, the answer is yes, although that type of progression is not that common. If it occurs, ⑤ usually closes off a gesture/phrase/sentence while ④ starts the next one. This is the case in both repertory examples above: the final D major chord of the Monte in both examples is followed by a C major chord in Wodiczka’s minuet and a Neapolitan sixth chord in Bach’s vivace.

While the Neapolitan sixth chord in Bach’s vivace is followed by a (regular) sixth chord on ③—a legitimate progression in itself, the more typical progression is that ④ goes to ⑤ and ♭➋ to ➐, a melody that creates an expressive melodic diminished third. (In G minor, this would be a♭(1/2)–f♯(1/2).)

The Three-Part Monte

Unlike a Fonte, a Monte can consist of more than two segments. Let’s look into the three-part Monte now, which can occur in two versions:

- in a version where the segments focus successively on IV, V and vi (only in major)

- in a version where the segments focus successively on IV, V and I (in major) or on iv, V and i (in minor).

The Major-Key IV–V–vi Monte

The third segment of a major-key IV–V–vi Monte continues the stepwise transposition upwards but changes mode, this third segment being written in the key of the submediant, that is, in the key of the relative minor (vi). In other words, while the first two segments are in major, the third segment is in minor.

Note that a chromatic semitone also occurs in the bass between segments two and three.

Riepel’s fictitious pupil states that a listener might hear the first two segments as a genuine Monte, thereby questioning the structural value of the three-part Monte. Riepel, however, approves of this type of Monte and explains that the listener will feel deceived (Er [ein Zuhörer] findet sich aber betrogen; Riepel, Anfangsgründe IV, p. 22) when hearing the third segment. So, it seems Riepel considers this a successful rhetorical gesture.

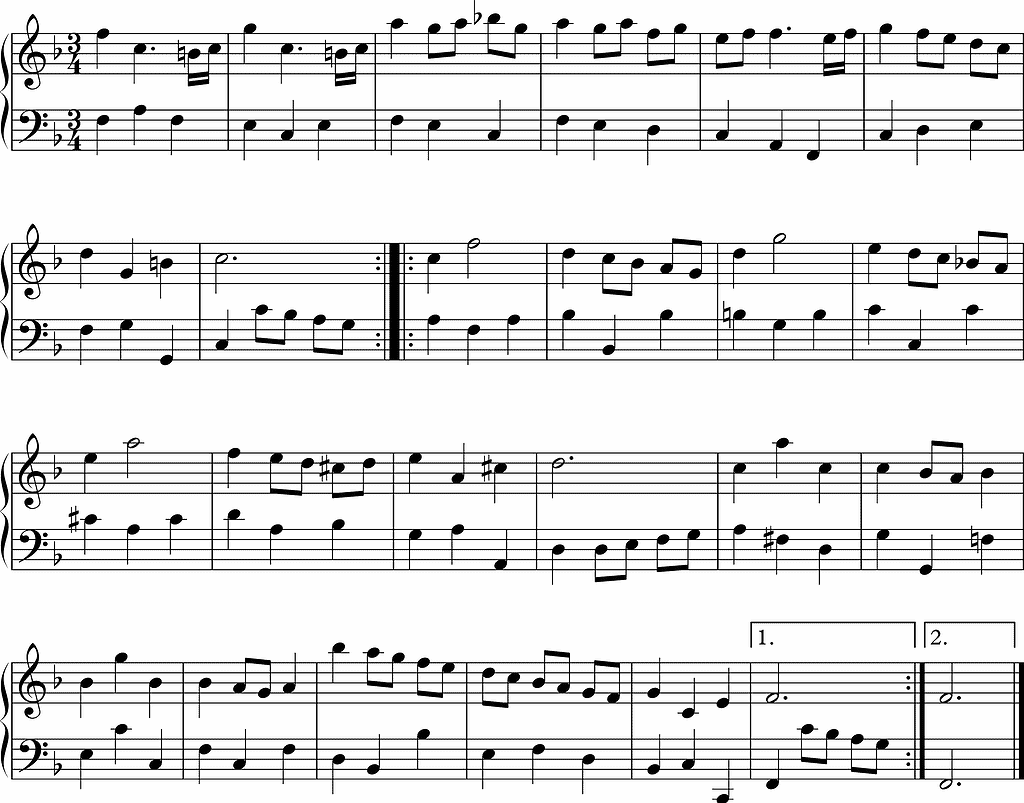

The next repertory example contains such a major-key IV–V–vi Monte, again in its common place after the double barline.

The key of this minuet is F major. After a perfect authentic cadence in C major that closes the first half (bars 7–8), the second half opens with a six-bar IV–V–vi Monte (bars 9–14). Its first segment focuses on B flat major (IV), its second on C major (V) and its third on D minor (vi). (Admittedly, there is some ambivalence regarding the key of the first segment as any e♭ is lacking. Still, in the context of the whole sequence, it is unlikely, especially in retrospect, not to interpret the first segment as a moment of B flat major. Moreover, ornamenting the d2 in the right hand on the first beat of bar 10 by playing an optional trill arguably works better with e♭2 than with e(♮)2.) This six-bar Monte is followed by two more bars in D minor, resulting in an eight-bar phrase that closes with a perfect authentic cadence in that key.

Note how this Monte is followed by a four-bar Fonte (bars 17–20). (I will elaborate on the possibility of a Fonte following a Monte, and vice versa, in a separate essay.)

The IV–V–I Monte and iv–V–i Monte

In this type of Monte, the third segment is not one step but a fourth higher than the second segment. Since the version in minor doesn’t really require any further elucidation and to limit the number of examples in this essay, I will give only one example of this type of Monte, an example in major.

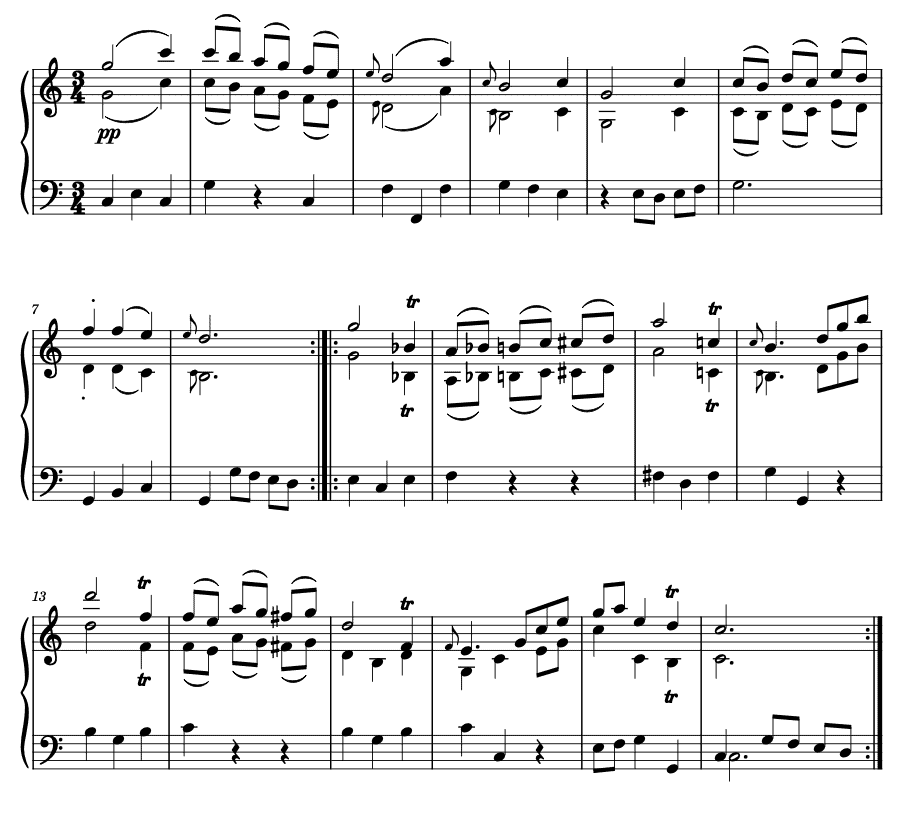

An elegant and expressive example of a IV–V–I Monte occurs at the beginning of the second half of a minuet in C major written by the Austrian composer and violinist Joseph Starzer (1726/27–1787) as part of his ballet Psiché et l’amour from 1752. The first segment of the Monte —in F major (IV)— occurs in bars 9–10. The following two bars repeat the segment one step higher —in G major (V)— with a varied second bar. As for the third segment (bars 13–14), it presents the same clausula cantizans this time in C major (I), thus a fourth instead of a second higher, again with a varied second bar.

Note how Starzer repeats the third segment of this Monte in bars 15–16, albeit in a varied manner. He puts the melody an octave lower, varies yet again the second bar (by transposing the melody of bar 12) and adds an actual third part to the texture in the second violin. (Reflections on how to phrase this minuet according to historical phraseology theories will be given in a series of essays devoted to this topic.)

The Four-Part Monte

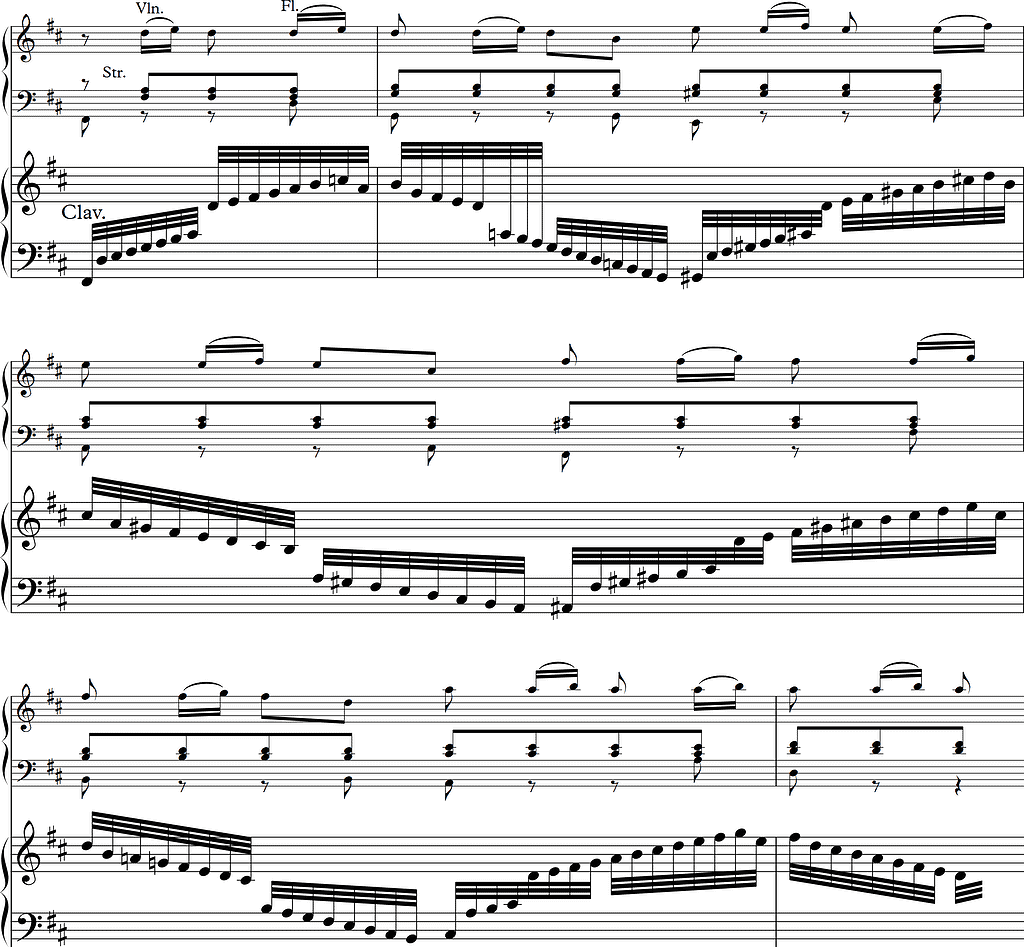

In major, the segments in vi and I can also follow each other as third and fourth segments of a four-part IV–V–vi–I Monte. The following excerpt from the first movement of Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg Concerto in D major BWV1050 shows such a four-part Monte, where the segments focus on the keys of G major (IV), A major (V), B minor (vi) and D major (I) successively:

(The harpsichordist in this recording of BB5 is yours truly, by the way.)

The Five-Part Monte

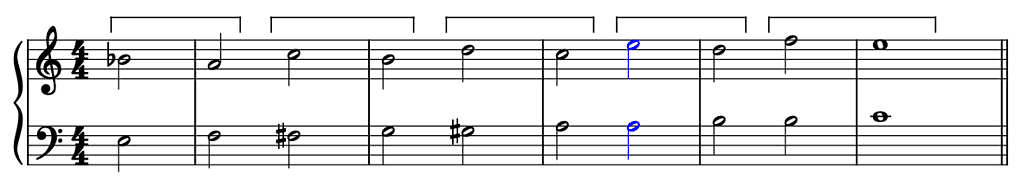

There is even a five-part Monte in major. The special feature of this type of Monte is its fourth segment, the one inserted between the segments that focus on vi and on I. Instead of focusing on the key of B minor (vii), which was considered too distant in this context, the fourth segment focuses on I, as does the fifth. Regarding segment 4, this explains why

- the melodic interval in the bass is a whole instead of a half step, a–b (⑥–⑦ in C major) instead of a♯–b (⑦–① in B minor)

- the first vertical interval isn’t a diminished but a perfect fifth (if a fifth is present), which I have indicated in blue in the next example:

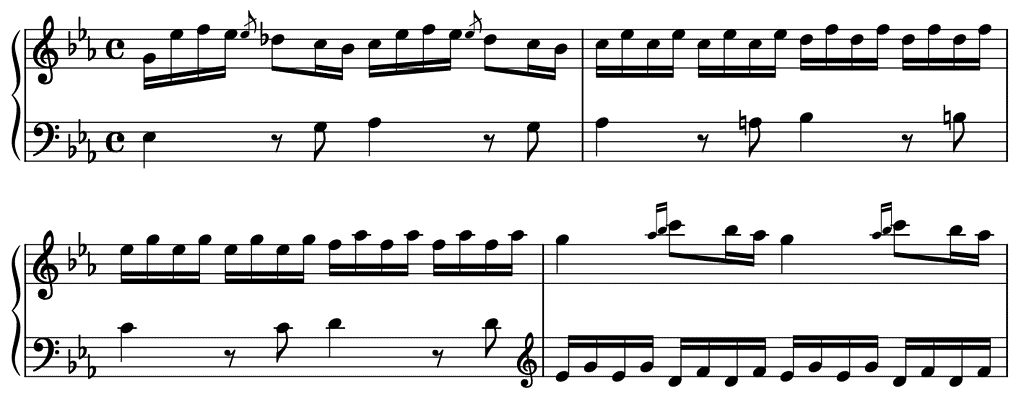

Cimarosa penned such a five-part Monte in a passage in E flat major as part of a keyboard sonata in C minor:

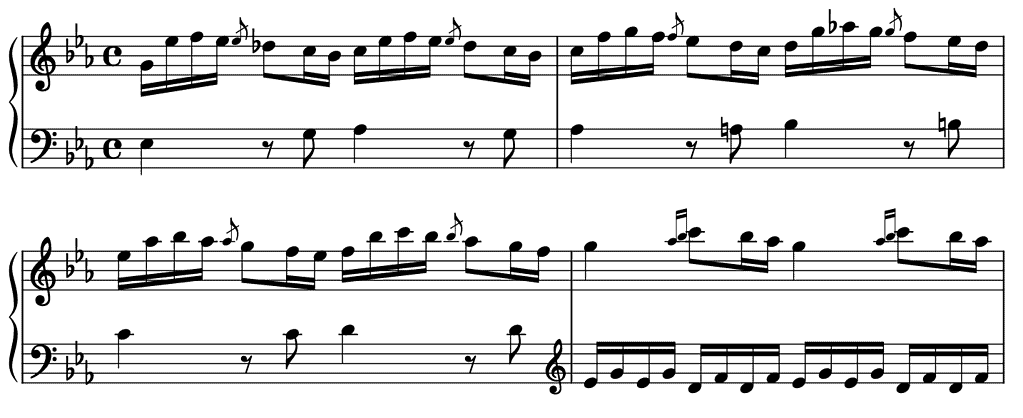

Note that this Monte is a telling illustration of the then first-choice relationship between metre and chord type. The unstable sixth chords fall on the second half of the weak beats, while the stable triads start on the strong beats. This organization probably also explains Cimarosa’s choice to change the texture on the downbeat of 31. Cimarosa could have continued using the decoratio of bar 30; see my hypothetical version below.

His solution, however, provides more variation and allows the left hand to imitate the texture of the right hand from bar 33 onwards.

Further Reading (Selection)

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Jayasuriya, David. Fonte and Monte in the Symphonies of Joseph Haydn, PhD Dissertation (University of Southampton, 2016).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — I. De Rhythmopoeïa, oder von der Tactordnung (1752).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — II. Grundregeln zur Tonordnung (1755).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — III. Gründliche Erklärung der Tonordnung (1757).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — IV. Erläuterung der betrüglichen Tonordnung (1765).