Clausula cantizans = ⑦–① cadence

Clausula altizans = ⑤/④–③ cadence

Clausula tenorizans = ②–① cadence

Clausula basizans (or bassizans) = ⑤–① cadence

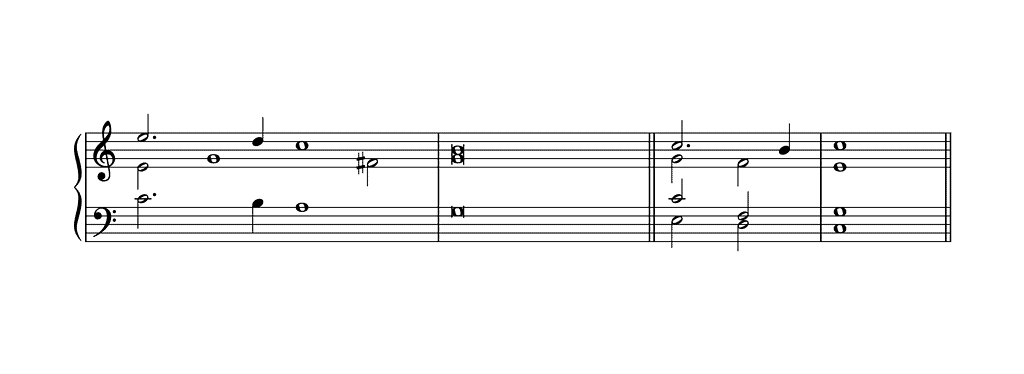

Treatises up to and including the first half of the 18th century mostly considered cadences from a melodic and polyphonic point of view. Instead of seeing a cadence in terms of a chord sequence, they stipulate that each individual part produces a specific type of melodic cadence, or clausula (plural: clausulæ). The reference point was a cadence that today we call a perfect authentic cadence, and more specifically a four-part (①–)⑤–① cadence with

- a (➊–)➐–➊ snippet in the soprano, called a clausula cantizans (from canto, the highest part)

- a (➎–)➎–➌ snippet in the alto, called a clausula altizans (this clausula can also consists of a (➎–)➍–➌ snippet)

- a (➌–)➋–➊ snippet in the tenor, called a clausula tenorizans.

As for the (①–)⑤–① snippet in the bass, it was called a clausula basizans (also spelt as bassizans).

In other words, what we call today a four-part perfect authentic cadence was usually considered to consist of four simultaneous clausulæ, one in each part.

Below you can see the labelling of each clausula and a ①–⑤–① cadence from Harmonologia musica oder kurtze Anleitung zur Musicalischen Composition (1702) by Andreas Werckmeister (1645–1706). (Werckmeister was a German composer, organist and music theorist best known today for his discussions on musical temperaments.)

Werckmeister further explains that any of these clausulæ can be assigned to the bass, that a clausula cantizans, a clausula altizans or a clausula tenorizans can also occur in the bass. In this case, the other clausulæ may, but need not, appear in the other parts.

While musicians in this time had a polyphonic approach to cadences, they often stipulated only the type of clausula that occurs in the bass. Below you see two examples of what has simply been labelled a clausula tenorizans, the one on the left from Tractatus compositionis augmentatus (between 1657 and 1663) by Christoph Bernhard (1628–1692), the one on the right from Praecepta der Musicalischen Composition (1708) by Johann Gottfried Walther (1684–1748):

(Christoph Bernhard was a German pupil of Heinrich Schütz, singer, composer, kapellmeister and author of three handwritten treatises on composition. Praecepta der Musicalischen Composition is a manuscript written for Prince Johann Ernst of Weimar by his teacher Johann Gottfried Walther, composer, violinist, organist, author, and friend and cousin of Johann Sebastian Bach.)

Select Bibiography

Bernhard, Christoph. Tractatus compositionis augmentatus, in: Die Kompositionslehre Heinrich Schützens in der Fassung seines Schülers Christoph Bernhard (fourth edition). Modern edition, ed. Joseph Müller-Blattau (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1926/2003).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Neuwirth, Markus. Fuggir la Cadenza, or The Art of Avoiding Cadential Closure — Physiognomy and Functions of Deceptive Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, in: What Is a Cadence? Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, ed. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015), p. 117–155.

Walther, Johann Gottfried. Praecepta der Musicalischen Composition (Weimar, 1708). Modern edition, ed. Peter Benary (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel (Jenaer Beiträge zur Musikforschung — Band 2), 1955).

Werckmeister, Andreas. Harmonologia musica oder kurtze Anleitung zur Musicalischen Composition (Frankfurt and Leipzig, 1702).