In this essay, I will explore how the Fonte can be extended.

While the Fonte is often composed of two segments, each of which consists of a ⑦–① cadence, this schema can be extended by adding an extra cadence to each segment or even by equating a musical phrase containing multiple cadential gestures with one segment.

Recap: What Is a Fonte?

The term and interpretation of the Fonte (Italian for well) comes from Joseph Riepel (1709–1782), chapel master in Regensburg. He describes the Fonte as a pattern that is often used as the opening gesture of the second half of a binary form in a major key. Riepel defines the Fonte as having two segments that are each other’s transpositions. The first segment is written in the minor key of the supertonic (e.g. D minor when the main key of the piece is C major), the second segment in the main major key, one step lower. In its typical form, each segment consists of a ⑦–① cadence (or clausula cantizans) with a ➍–➌ melody. For more information see my essay The Fonte: The Basics.

Each Segment Consists of Two Different Cadences

Adding an extra cadence is a simple way of extending a Fonte, the simplest of which is by repeating each clausula cantizans. When expanding a Fonte, however, 18th-century composers more often chose to vary the type of cadence. In my essay The Fonte: The Basics, I already pointed out a type of extended Fonte in which each segment consists not of one but of two different cadences. Consider the following example.

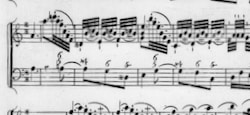

Menuetto (Fonte: bars 9–12),

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

The second half of this minuet starts with a Fonte in which each segment opens with a ⑦–① cadence (bars 9 and 11) followed by a ⑤–① cadence (bars 10 and 12). That way, this Fonte is twice as long as it would have been if each segment consisted of only one cadence lasting one bar. The fact that a ⑤–① cadence instead of a ⑦–① cadence closes off each segment results in more affirmative conclusion. And the fact that each ⑤–① cadence presents a ➐–➊ melody results in an imitation between the bass and the melody.

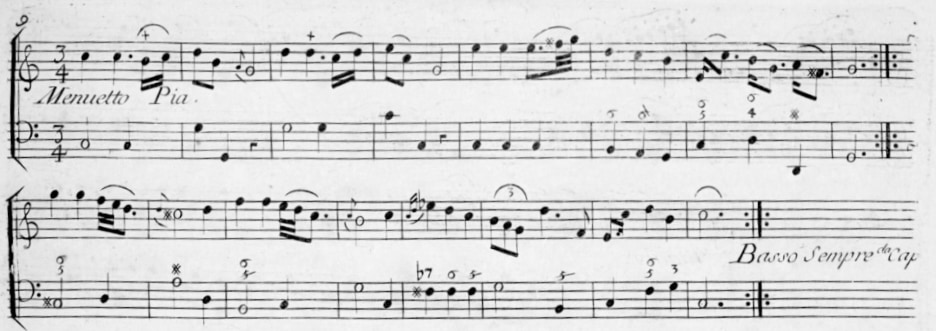

A similarly extended Fonte occurs at the beginning of the second half of a minuet in F major Mozart wrote in January 1762, when he was about to turn six. (I already discussed this minuet to some extent in my essay The Fonte: The Basics.)

Each segment of the Fonte consists again of a ⑦–① cadence (bars 9–10 and 13–14), which is followed by a ⑤–① cadence (bars 11–12 and 15–16). However, there are several differences with the previous Fonte. First, every cadence lasts two bars instead of one. Secondly, obviously for reasons of motivic coherence, Mozart decides to set the ⑦ of each ⑦–① cadence as a seventh chord instead of a 6/5 chord. (As I mentioned in my essay The Fonte: The Basics, Gjerdingen calls this variant of a ⑦–① cadence a Jommelli.) Since Mozart respects the scales of G minor and F major in each segment, respectively, the first seventh chord is diminished with F♯ in the left hand and E♭ in the right hand (bar 9), the second half-diminished with E in the left hand and D in the right hand (bar 13). Thirdly, each ⑤–① cadence is preceded by a sixth chord on ④, giving it slightly more structural impact.

While Wodiczka wrote his minuet in C major with two equally long halves of eight bars, Mozart decided to write a second half that is twice as long. To balance the Fonte that lasts eight instead of four bars, two four-bar phrases conclude this minuet. The first is a broken cadence, which is emphasized with the fermate in bar 20, the second one a perfect ⑤–① cadence.

Above I have ‘composed’ a hypothetical version of this minuet with both halves lasting eight bars. While it works perfectly, it does lack the eloquence and flair of Mozart’s original.

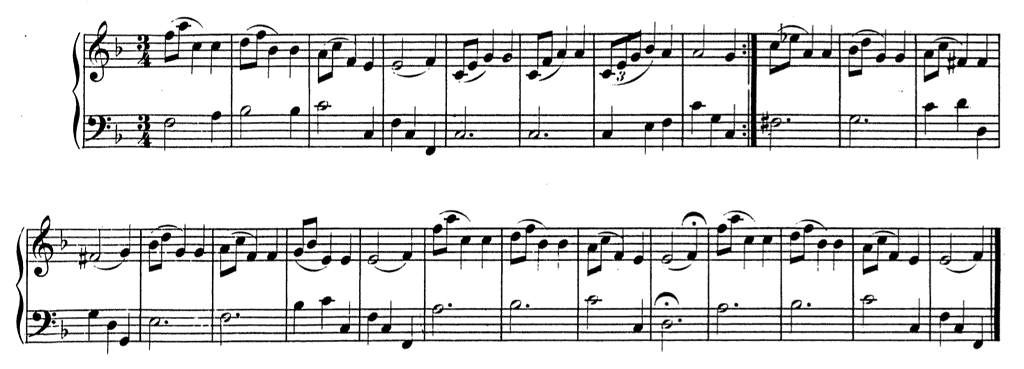

In the examples above, a ⑤–① cadence was added after the clausula cantizans. Any kind of cadence, however, can be used anywhere in the Fonte. In the third section of the extensive minuet from his violin sonata no. 1 in D major opus 1, Pierre Gaviniés (1728–1800) writes a Fonte with another succession of cadences. (This Fonte opens the second half of the third section of the minuet. Gaviniés decides to write out the repeats of this minuet, what explains the absence of a double barline preceding the Fonte.) In this case, a clausula cantizans closes off each segment and is preceded by a ④–③ cadence or clausula altizans.

Tempo di Menuetto, bars 86–93 (Fonte: 87–91a),

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

(Gjerdingen would probably call this succession of cadences a Fenaroli. I will come back to this voice-leading pattern in a yet-to-be-published essay.)

Each Segment Consists of a Musical Phrase

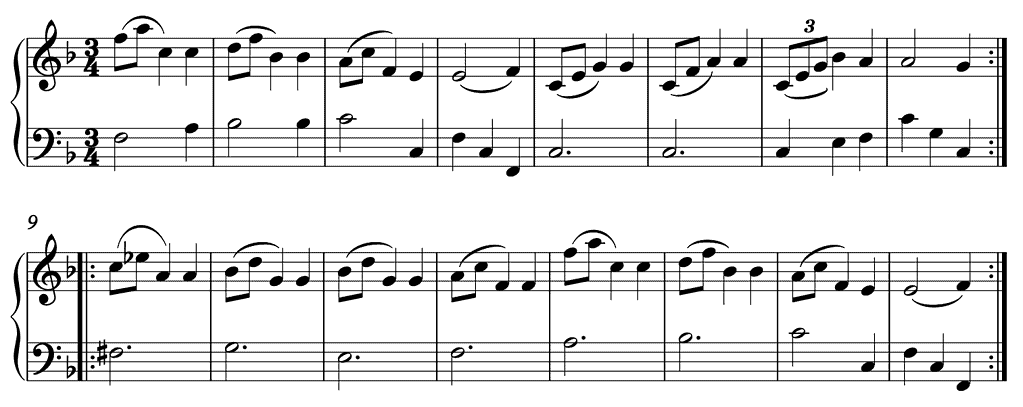

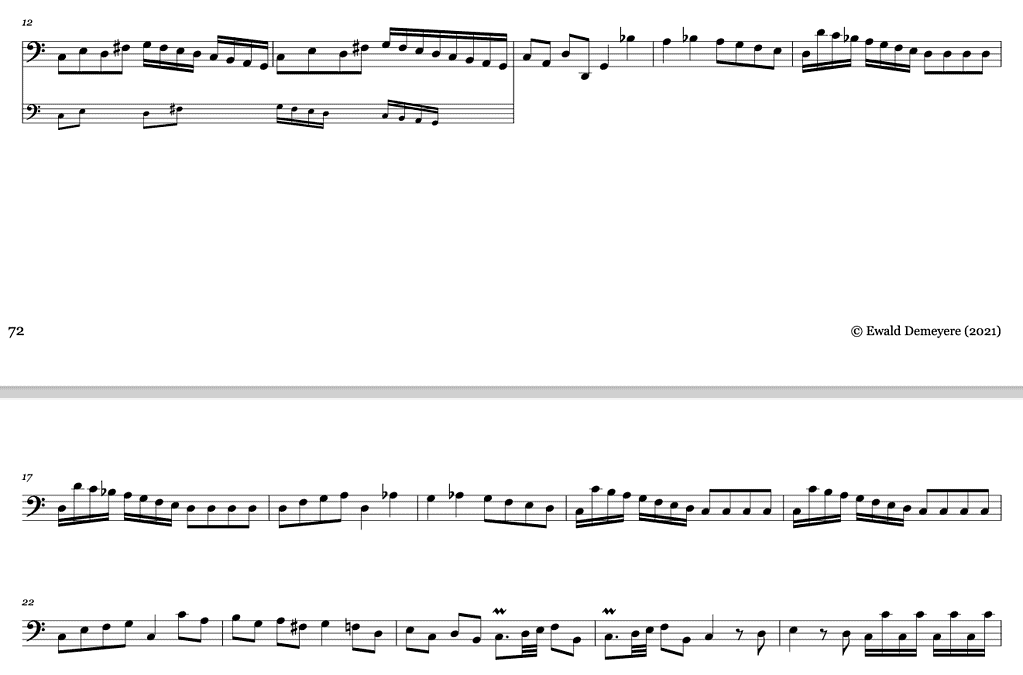

Each segment of the Fonte can also consist of an entire musical phrase, including multiple cadential gestures. Consider the following example, which is a fragment from partimento no. 38 in C major from Book 3 by the Neapolitan partimento and counterpoint maestro Fedele Fenaroli (1730–1818).

(Note that the fragment above is an excerpt from my critical edition of Fenaroli’s first three books of partimenti, which can be downloaded from https://essaysonmusic.com/resources/.)

As is always the case in the pedagogical corpus of Fenaroli, also this partimento reflects a genuine musical form. The first three beats of bar 14 represent the final cadence of the first half of what seems to have been intended as an allegro movement. A phrase in D minor opens the second half of this partimento (from beat 4 of bar 14 to beat 3 of bar 18) and is followed by its transposition to C major, both phrases constituting a Fonte.

Note how Fenaroli decided to transpose the first four bass notes of the Fonte’s first segment literally in order to preserve the semitones between them. That way, the hermaphrodite note —➏♭— appears twice in the bass at the start of the C-major phrase.

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fedele Fenaroli, METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE, Preface and Editorial Principles by Ewald Demeyere, 2021

Prinner, Johann Jacob. Musicalischer Schlissl (1677).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — II. Grundregeln zur Tonordnung (1755).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — III. Gründliche Erklärung der Tonordnung (1757).

Secondary Sources

Demeyere, Ewald . On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207-229.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).