The Fontes we saw until now all finish in the main (major) key. However, there are types of Fontes that relate to another key than the main key.

In this essay, I will explore three types of Fonte that do not relate to main (major) key: the Fonte that finishes in the dominant key, the Fonte that finished in the subdominant key and, when the main key is minor, the Fonte that finishes in the parallel major, aka the borrowed Fonte.

Recap: What Is a Fonte?

The term and interpretation of the Fonte (Italian for well) comes from Joseph Riepel (1709–1782), chapel master in Regensburg. He describes the Fonte as a pattern that is often used as the opening gesture of the second half of a binary form in a major key. Riepel defines the Fonte as having two segments that are each other’s transpositions. The first segment is written in the minor key of the supertonic (e.g. D minor when the main key of the piece is C major), the second segment in the main major key, one step lower. In its typical skeletal form, each segment consists of a ⑦–① cadence (or clausula cantizans) with a ➍–➌ melody. For more information see my essay The Fonte: The Basics.

The Fonte That Finishes in the Dominant Key

Although Riepel does not go so far as to ban a Fonte that finishes in the dominant key, he does find it “so strange that it rightly belongs to the special tone arrangement” (so fremd, daß er mit Recht zur Tonordnung ins besondere gehört; Riepel, 1757: 2). This is the example he gives of this type of Fonte:

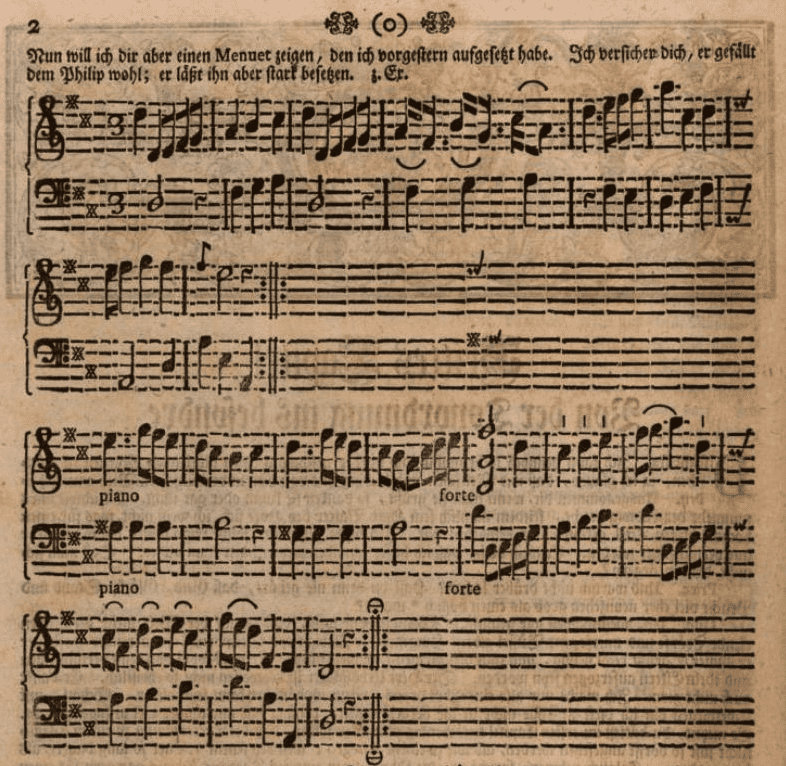

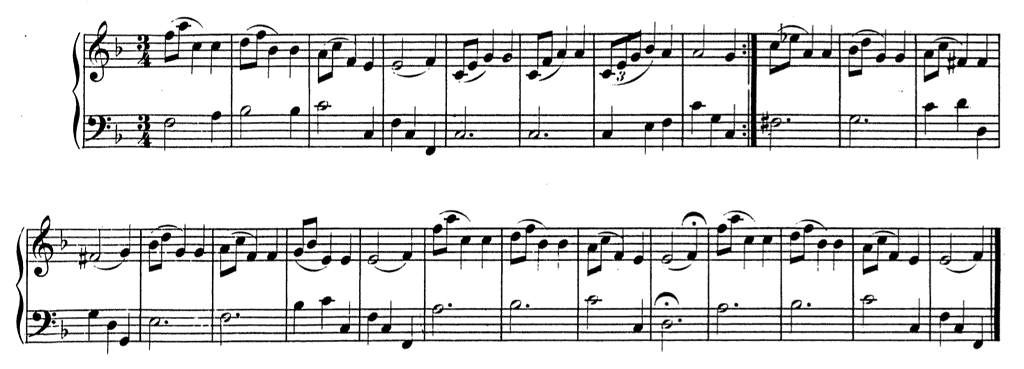

A composer like Domenico Cimarosa, however, doesn’t find anything strange about the Fonte that finishes in the dominant key since this type of Fonte is one of the composer’s favourite gestures at the start of the second half of a binary form. Consider the following example, a fragment from an allegretto in C major by Cimarosa.

This example shows the end of the first half that ends in G major and the beginning of the second half. As you can see and hear, the second half does not start in D minor, as would have been the case with a ‘regular’ Fonte, but in A minor (bar 11b). The A minor segment consists not of one but of two consecutive ⑦–① cadences, a segment repeated a tone lower in G major (bars 12b–13).

Compare now Cimarosa’s version with mine, which includes a regular Fonte that starts in D minor and concludes in C major:

I would argue that this version works equally well as Cimarosa’s and that the decision to write a regular or a Fonte that finishes in the dominant key is an artistic one and/or depends on how one wants to continue after it.

The Fonte That Starts in the Dominant Minor Key and Finishes in the Subdominant (Major) Key

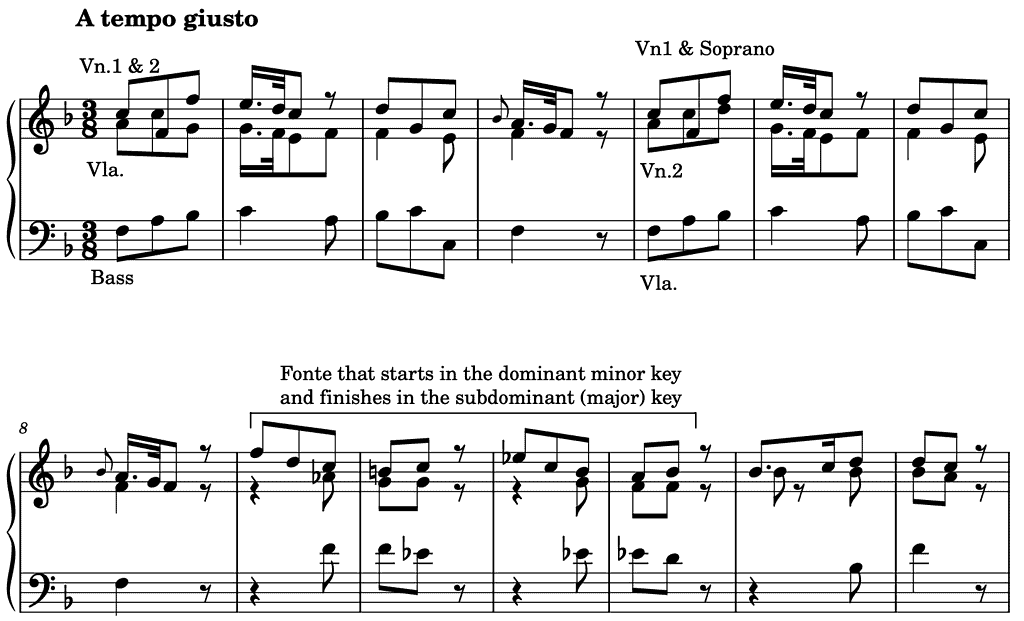

On 3 January 1722, the comic opera Li zite ‘n galera (The lovers on the galley) by Leonardo Vinci (ca. 1696–1730) had its premiere in the Teatro de’ Fiorentini, an opera house in Naples that focussed on commedia per musica. (Vinci was a successful Italian opera composer who studied at the Neapolitan Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo.) Li zite ‘n galera, sung in Neapolitan dialect, is Vinci’s first comic opera to have survived as a complete score. The second aria of the second act of this opera opens as follows:

(top voice in bars 1–4: violins 1 & 2, top voice in bars 5–14: violin 1 & soprano, middle voice in bars 1–4: viola, middle voice in bars 5–14: violin 2, bass part in bars 1–4: bass group, bass part in bars 5–14: viola; Fonte that finishes in the subdominant key: bars 9–12)

The four-bar instrumental introduction of this aria is repeated in bars 5–8 as the soprano’s first phrase. As you can see and hear, both phrases conclude with a ⑤–① cadence in the main key of F major. Hereafter, in bars 9–10, Vinci writes a clausula altizans or ④–③ cadence in C minor (instead of C major, which is obviously the first choice in the context of a piece in F major). In bars 11–12, Vinci transposes this cadence one tone down to B flat major. As explained above, the succession of a cadence in a minor key and the same cadence in the major key one tone lower is the essence of a Fonte. In this case, however, the Fonte does not relate to the main or to the dominant key but to the subdominant key, a type of Fonte that is quite rare especially if the first segment is set in the dominant minor key. Still, the key relationship of a regular Fonte that finishes in the main key and its preceding phrase —usually in the dominant key— is the same as that of this type of Fonte and its preceding phrase in the main key. In both cases, the Fonte starts in the minor key a fifth higher than the preceding major key. Compare Vinci’s example with KV2 for instance:

(For more information on the Fonte in KV2 see my essay Extending the Fonte.)

Interestingly, while one expects to hear some kind of cadence in F major following this Fonte that starts in the dominant minor key and finishes in the subdominant key, Vinci decides on confirming the key of its second segment, B flat major, by adding several phrases and cadences in that key. So in retrospect, this Fonte seems to become regular with regard to its key organization when viewed from the key of B flat major.

As far as I know, the Fonte that starts in the dominant minor key and finishes in the subdominant key has not yet been identified.

The Borrowed Fonte

As we have seen, the Fonte is in fact a schema that occurs only in the context of a major key. Indeed, in a galant piece in C minor, for example, the modulation to D minor is not only somewhat unusual in itself, but the sequence D minor – C minor is also ‘not done’. In a minor key, this makes not the Fonte but the Monte the first compositional choice after the double barline in the middle of a binary form. (Just as a Fonte, a Monte is a sequential schema in which each segment constitutes a cadence, often a clausula cantizans as well. However, while a Fonte is a descending pattern starting in the (minor) key of the supertonic, the Monte is an ascending pattern starting in the key of the subdominant. I will explore the Monte in a series of yet-to-be-published essays.) Nevertheless, Fontes do also occur in pieces in minor keys, but then relate not to the main (minor) key but to the relative (major) key, a type of Fonte Riepel calls “borrowed” (“entlehnet”; Riepel, 1755: 123).

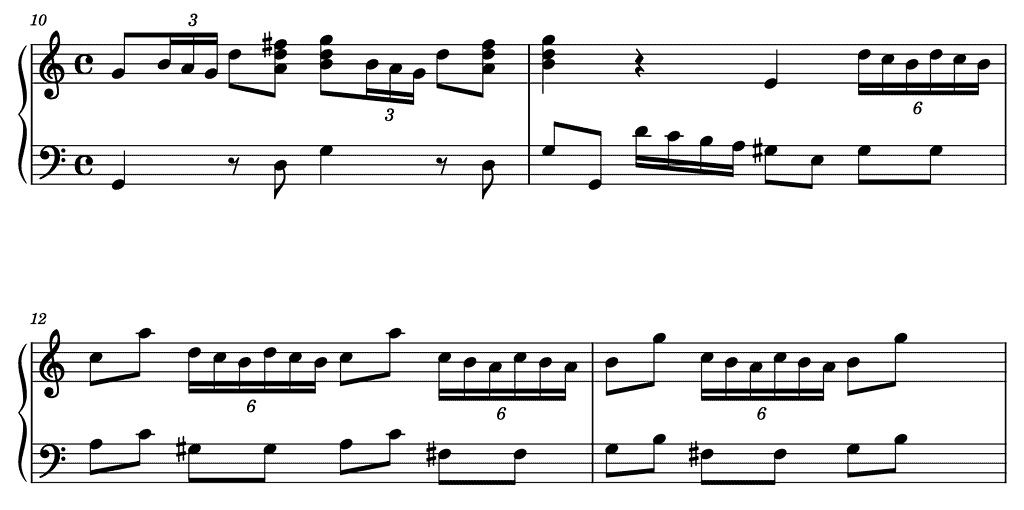

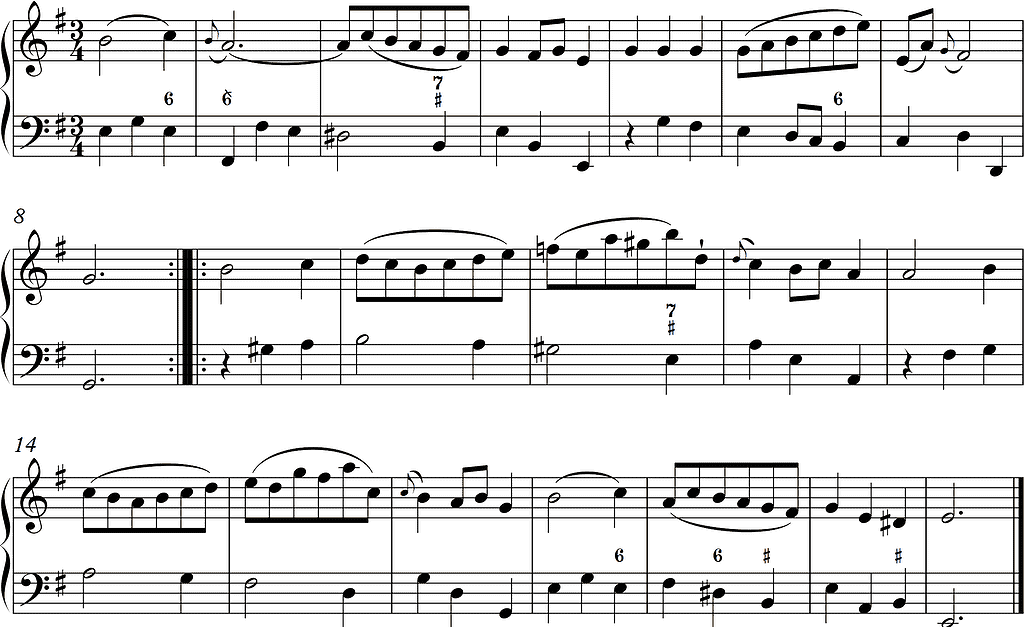

2em Menuetto (in E minor; Borrowed Fonte: bars 9–16)

The example above shows a borrowed Fonte after the double bar line, a Fonte in which each segment lasts four bars. The key of its first segment is A minor (bars 9–12), that of its second segment G major (bars 13–16), the relative major of E minor, which is the key of this sonata and minuet.

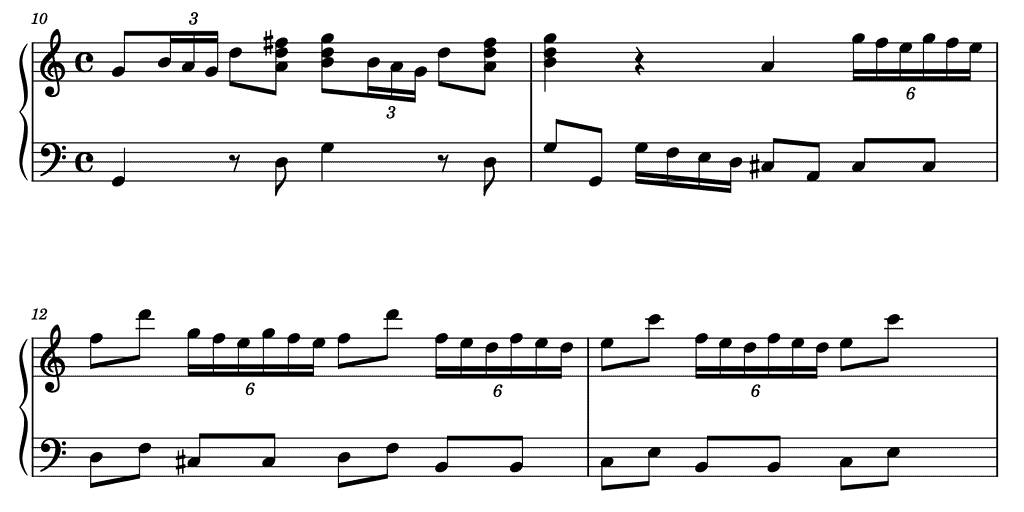

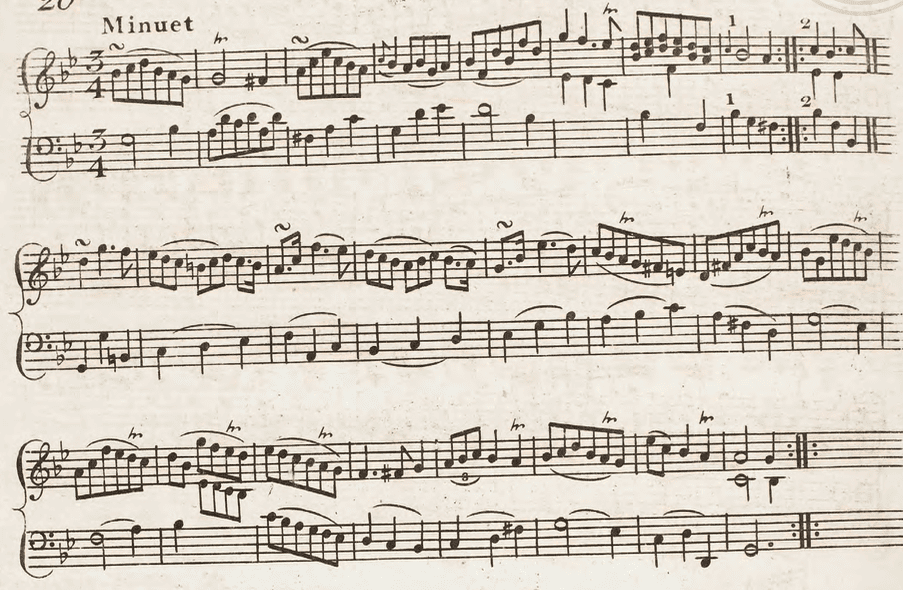

In 1783, Jane Savage (1752/53–1824) published her Six Easy Lessons for the Harpsichord or the Piano Forte opus 2. (Jane was an English keyboardist, composer and daughter of William, an organist, bass singer and composer.) After the double bar line of the minuet of the last sonata in B flat major, a borrowed Fonte occurs which is extended into a descending sequence of four segments to return to the main key of this minuet, G minor:

Notice how the music reverts back to B flat major again at the beginning of the third system. This seems a questionable compositional decision since this key has occurred twice before —at the end of the first half of the minuet and again during the second segment of the borrowed Fonte— and the music returns to the main key of G minor towards the end of the second system.

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Prinner, Johann Jacob. Musicalischer Schlissl (1677).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — II. Grundregeln zur Tonordnung (1755).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — III. Gründliche Erklärung der Tonordnung (1757).

Secondary Sources

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Jayasuriya, David. Fonte and Monte in the Symphonies of Joseph Haydn (Southampton: University of Southampton, 2016 (PhD dissertation)).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).