This essay is the first of two exploring a schema that Robert O. Gjerdingen has labelled Quiescenza (Italian for a state of repose or inactivity).

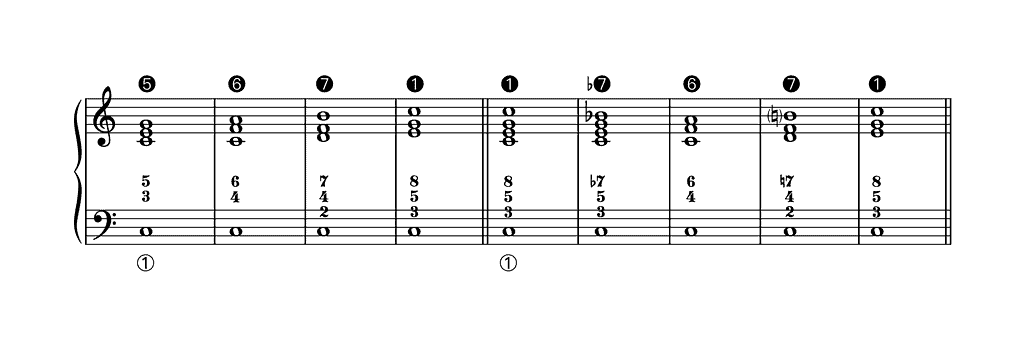

A Quiescenza is a tonic pedal point with four or five sonorities, 5/3 – [7♭/5/3 –] 6/4 – 7(♮)/4/2 – 8/5/3, and a ➎–➏–➐–➊ or ➊–♭➐–➏–(♮)➐–➊ treble line that can be used as a proposta schema or occur in a closing passage.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in an upper part (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①.

Note further that ‘Bar 1a’ refers to the first half of bar 1, ‘bar 1b’ to its second half.

Term and Interpretation

The term and interpretation of the Quiescenza come from Robert O. Gjerdingen. He defines this schema as a tonic pedal point with several strongly related settings. In this essay, I will elaborate on the settings based on four or five sonorities, [8/]5/3 – [7♭/5/3 –] 6/4 – 7(♮)/4/2 – 8/5/3, and two possible treble lines with four or five structural notes, ➎–➏–➐–➊ or ➊–♭➐–➏–(♮)➐–➊, lines that usually appear in the treble but can also appear in a middle part.

(Other settings are discussed in my essay Some More Quiescenzas.)

Structural Use

Gjerdingen argues that the Quiescenza often served as a proposta schema in the first half of the 18th century, while in the second half it was used more in closing passages (Gjerdingen (2007), p. 183). And in a video on the Quiescenza (beginning with ➊–♭➐), Seth Monahan rightly points out that a Quiescenza that occurs in a closing passage is often repeated with its characteristic melody easily discernible. As for a Quiescenza used as a proposta schema, it usually appears only once with its characteristic melody broken up between different parts. (Note that Seth Monahan identifies the Quiescenza only with the version beginning with ➊–♭➐, without mentioning other possible openings. Similarly, John Rice, in the commentary section of a video on the Quiescenza (with ♭➐), describes the Quiescenza as “a voice-leading schema characterized by a treble line that traces the scale degrees 8 – flat 7 – 6 – natural 7 – 8 over a tonic pedal”.)

The Quiescenza With ➎–➏–➐–➊

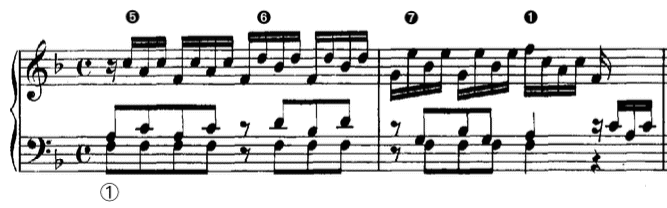

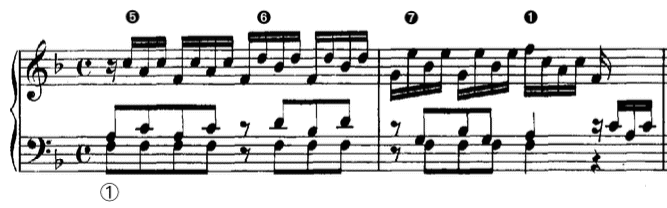

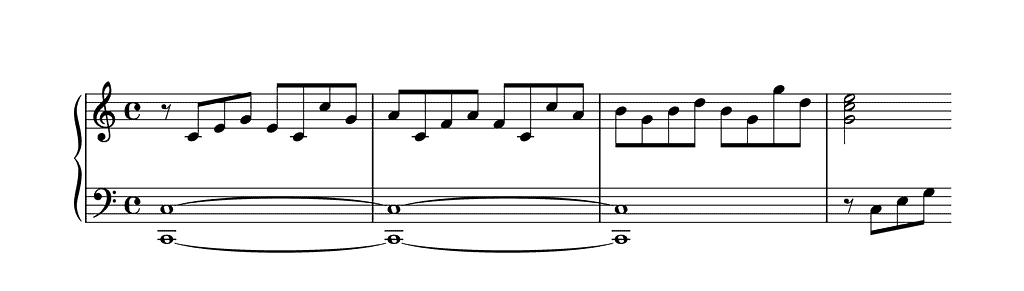

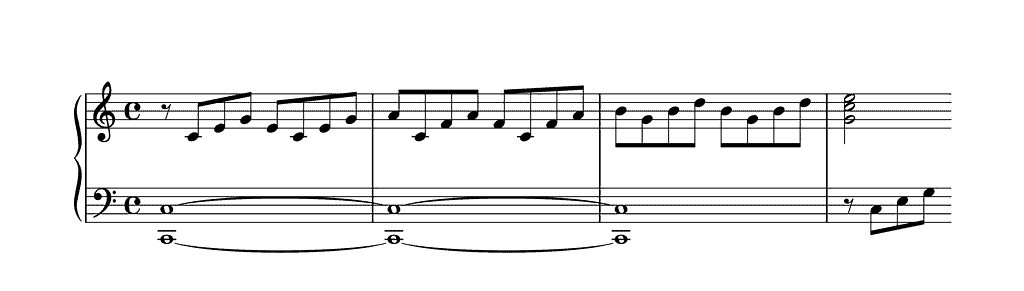

Johann Sebastian Bach regularly used the Quiescenza as a proposta schema. Below you can see two examples including a ➎–➏–➐–➊ line.

(Whether or not this composition is by Bach’s hand is not the issue here. That it belonged to the Bach circle is a fact: it appears in the Klavier-Büchlein vor Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, a keyboard book his father began compiling on 22 January 1720, two months after Friedemann’s ninth birthday.)

In the examples above, notice

- the tonic pedal point

- the rising melodic fourth ➎–➏–➐–➊, which occurs in BWV927 in the implied upper part, in BWV1007 in the implied middle part

- the progression with four sonorities 5/3 – 6/4 – 7/4(/2) – 8/5/3.

While preserving the tonic pedal point and these four structural sonorities, Bach also wrote Quiescenzas used as a proposta schema in which the rising melodic fourth ➎–➏–➐–➊ is less or not at all discernible as a melodic gesture in one (implied) part. (As mentioned above, this tends to be a general feature of opening Quiescenzas.) In the following example, in minor, the rising melodic gesture in the treble breaks off after ♭➏ and is followed by a descending snippet ➍–♭➌. This is probably because ♭➏ suggests that the melody should descend.

Note that 6♭ has been added to the 7(♮)/4/2 sonority in bars 5–6.

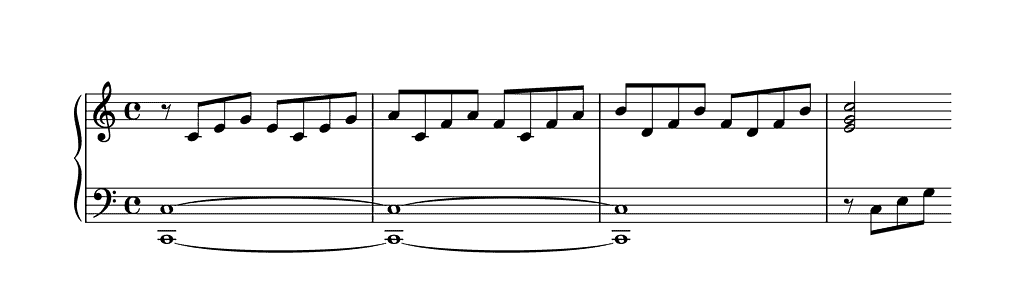

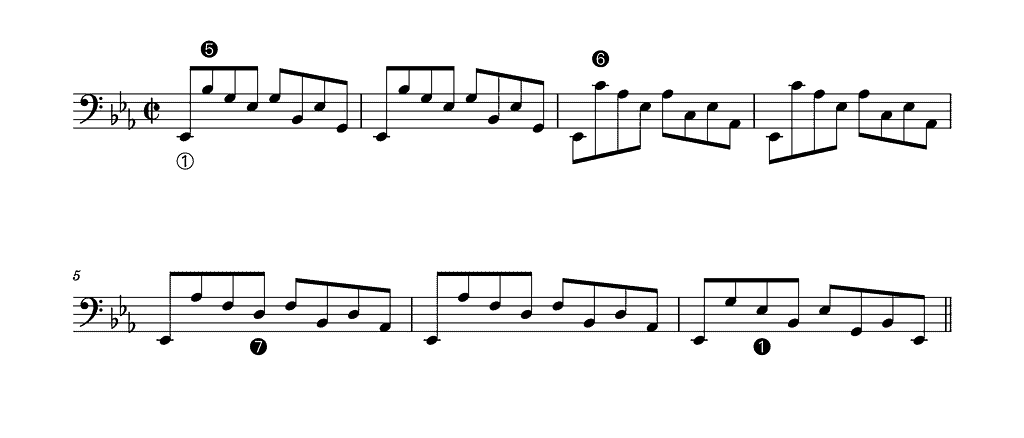

And because in the next example the overall progression is (predominantly) descending, a clearly discernible rising melodic fourth ➎–➏–➐–➊ is altogether absent. Below the example, you can see two rhythmic reductions clarifying this.

While each Quiescenza in these examples by Bach is used as a proposta schema, any kind of Quiescenza can also appear in the latter stages of a section or of a composition, a structural possibility that became increasingly fashionable in the second half of the 18th century. In that case, as Gjerdingen notes, it usually appears twice in succession, is often announced by a trill on ➋ and serves as prolongation of ① of a clausula basizans. Moreover, the characteristic ➎–➏–➐–➊ treble line is usually easily discernible. To illustrate this type of Quiescenza, Gjerdingen discusses the following example by L’Abbé le Fils (1727–1803), the sobriquet of Joseph-Barnabé Saint-Sévain (Gjerdingen (2007), p. 184–185):

(Composer and violinist L’Abbé le Fils studied with Jean-Marie Leclair, also a composer and violinist. While he and his father worked as maître de musique at the church of St Caprais in Agen, they took minor orders, thus leaving his family the sobriquet ‘L’Abbé’.)

Note

- that stage 1 (with ➎) doesn’t coincide with the beginning of the tonic pedal in the bass, but appears one beat later

- how the thoroughbass figures clarify the structural sonorities of the Quiescenzas

- that the pair of Quiescenzas is followed by another clausula basizans —more precisely a Cudworth cadence, which in turn is followed by a Final Fall.

Note also how this example illustrates well that the first three sonorities of a Quiescenza with a ➎–➏–➐–➊ treble line are metrically subordinate to and lead to the last sonority, a metrical hierarchy resulting from the fact that the last stage of a Quiescenza with a ➎–➏–➐–➊ treble line is the most stable, with a first scale step both in the bass and in the melody. It goes without saying that this is an important insight when performing this kind of Quiescenza, especially when its metrical organization is less evident from the notation. Let’s look again, for example, at the Quiescenza opening BWV927.

If one were to play these two bars according to standard 18th-century performance practice rules for a 4/4 time signature, the first half of each bar would be played ‘better’ than the second half. (For more information on how metre guided 18th-century performance practices see Chapter 2 On Metre from my 2013 book Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue — Performance Practice Based on German Eighteenth-Century Theory.) However, these guidelines were flexible and adaptable to the situation. Since the final stage of this Quiescenza —metrically the strongest— coincides with bar 2b, bar 2b is metrically stronger than bar 2a.

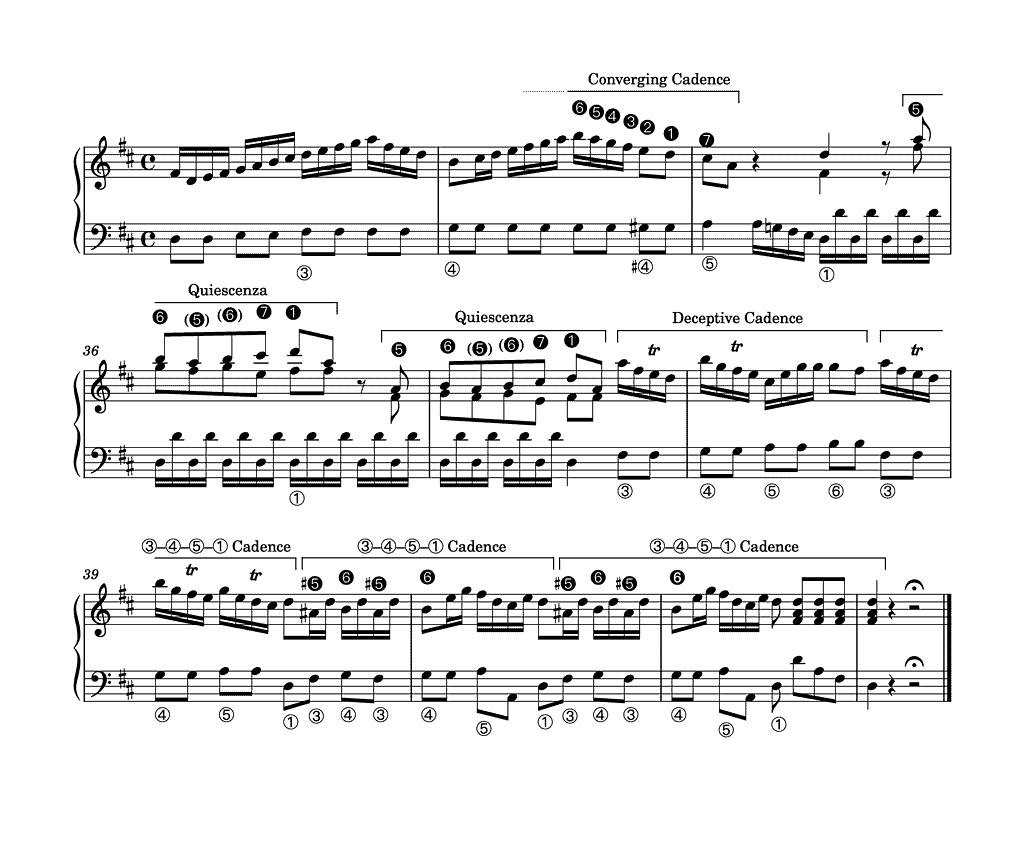

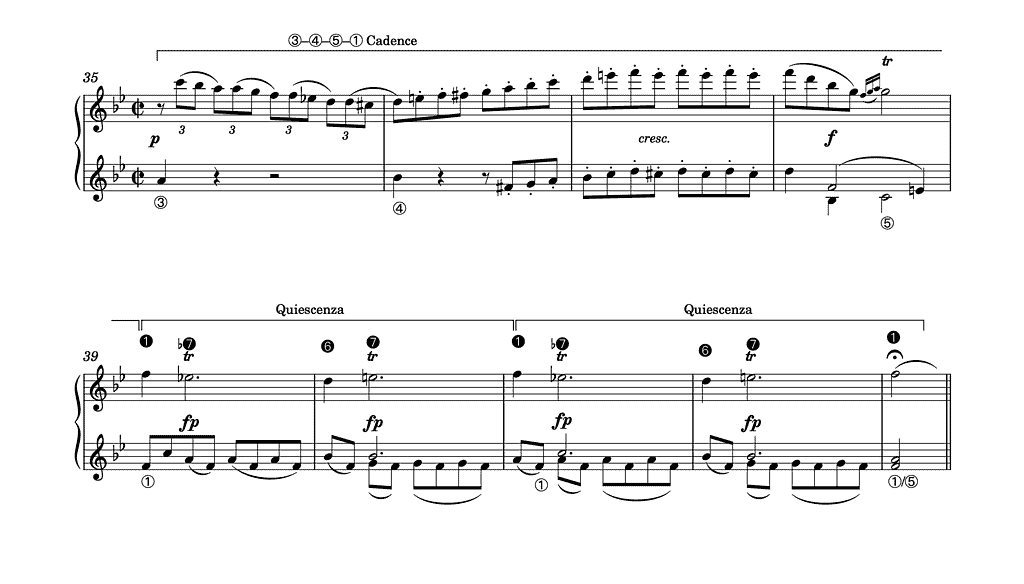

Another galant composer who wrote Quiescenzas with a ➎–➏–➐–➊ treble line is Domenico Cimarosa. Below is an excerpt from two of his many keyboard sonatas, each with a pair of metrically irregular Quiescenzas. I intentionally show these Quiescenzas in a somewhat larger context. My purpose here is to illustrate that instead of beginning a composition or serving as the prolongation of ① of a clausula basizans, they begin the final section/passage of these pieces, in both sonatas following a Converging cadence. As such, this observation puts Gjerdingen’s probability estimate that a Quiescenza is unlikely to be preceded by a Converging cadence (or more generally by a half cadence; Gjerdingen (2007), p. 372) and Vasili Byros’s assessment that a Quiescenza is a postcadential formula (Byros (2013), p. 228) somewhat into perspective. (Towards the end of Music in the Galant Style, on page 372, Gjerdingen inserts a chart based on a “small but representative sample of galant music” —the 14 compositions he discusses in chapters 5, 8, 10, 12, 15, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 28 and 29 (Gjerdingen (2007), p. 496, footnote 11)— to “compute the probability of any schema leading to any other schema”.)

Note

- the High ➏ Drop during the Converging cadence (bar 34b)

- that the Quiescenzas are embedded in such a way that they create a metrical shift, so that we hear the actual barlines in the middle of bars 35, 36 and 37 (the metrical shift continues even until the end of the sonata)

- that stage 1 (with ➎) doesn’t coincide with the start of the tonic pedal point in the bass but appears a beat and a half later (compare with the example of L’Abbé le Fils we saw above, where stage 1 appears one beat later than the start of the tonic pedal in the bass)

- that the Quiescenzas are followed by four cadences, one deceptive (bars 37b–38) and three perfect ⑤–① cadences, the first of which is a variant of the deceptive cadence and the last two of which are identical

- ♯➎ in the sixth chords on ③ at the beginning of the last two ③–④–⑤–① cadences (bars 39b and 40b), a typical galant feature when a sixth chord on ③ progresses to a triad on ④ in a major key

- how the ③–④/♯➎–➏ snippets in bars 39b–40a and 40b–41a are repeated, with the downbeats of bars 40 and 41 serving as tiny, temporary goals within the ③–④–⑤–① cadences

that the same passage, in A major and also metrically shifted, concludes the exposition of this sonata (not shown).

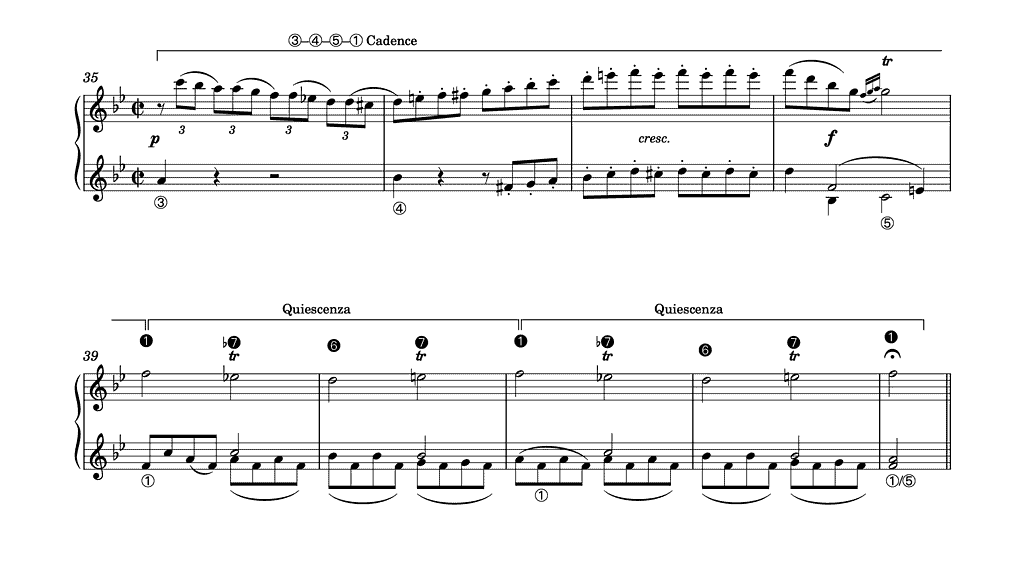

Note also that the ➎–➏ snippet appears twice in both Quiescenzas, the second appearance of which is purely ornamental, the reason why I have put the second ➎–➏ snippet in parentheses in the example above. Indeed, the first three eighth notes of bars 36a and 37a act as a neighbour-note motive embellishing the implied dotted quarter-note six-four chord. The following rhythmic reduction makes this clear:

The reduction also makes it clear that the stages of a Quiescenza do not necessarily have to be of equal length.

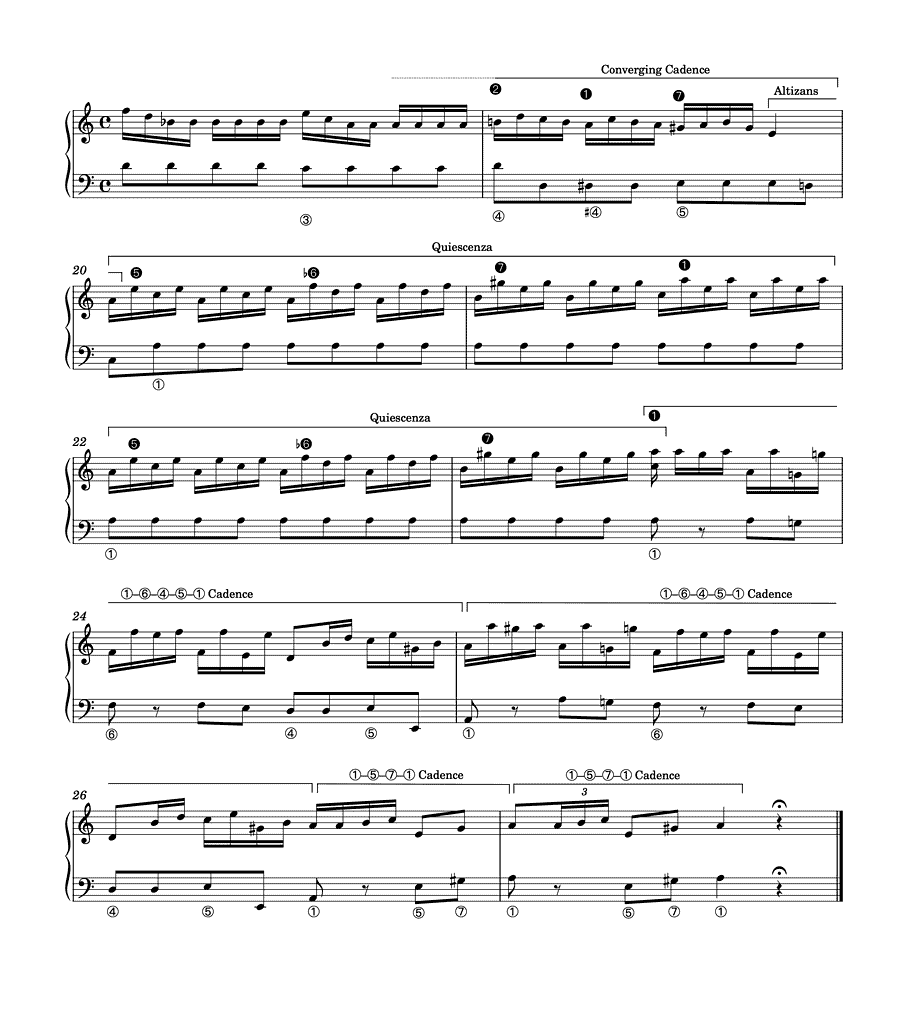

The following example illustrates how Cimarosa uses a pair of Quiescenzas in minor, each with a rising melodic fourth ➎–♭➏–➐–➊. (Unlike Bach with regard to the Quiescenza opening BWV999, Cimarosa clearly wasn’t bothered by the augmented melodic second ♭➏–➐.)

Note

- how the Converging cadence merges with a clausula altizans in bar 19b–20a

- the ♯7/5/2 instead of ♯7/4/2 sonorities in bars 21a and 23a.

Note also that this excerpt is metrically more irregular than the previous one:

- Beat 3 of bar 19 is metrically stronger than beat 1: beat 3 is the final chord —a major triad on ⑤— of the Converging cadence, while beat 1 —a lighter sixth chord on ④— leads to this triad. (In the previous example, the final chord of the Converging cadence falls on the downbeat of bar 35.)

- While both Quiescenzas start on a written downbeat, as their first three stages act as a long upbeat to stage 4, beat 3 of bars 21 and 23 is metrically the strongest.

- The Quiescenzas are followed by two ①–⑥–④–⑤–① cadences, each of which coincides with an implied bar of 3/2 (bars 23b–24 and 25–26a).

- And the sonata ends with two shorter ①–⑤–⑦–① cadences, the first in a metrically shifted bar of 4/4 (bars 26b–27a), the second in an implied bar of 2/4 (bars 27b). (One could also interpret these final cadential progressions as being embedded in three implied bars of 2/4.)

The Quiescenza With ➎–(♭➐–)➏–➐–➊

Since the first two sonorities of a Quiescenza are based on the triads of ① and ④, there is a possibility of using ♭➐ as an embellishment of ➎. (To indicate the ornamental nature of ♭➐, I have put it in parentheses in the title.) In a major key, this results in a brief glimpse of the key of ④, the opening triad of the Quiescenza being transformed into a dominant seventh chord. Let’s go back to Bach again, to the start of his Little Keyboard Prelude in F major BWV939, another example of a Quiescenza used as a proposta schema.

Like the Quiescenzas we saw above, this exemplar is essentially composed of the following elements:

- four structural sonorities 5/3, 6/4, 7/4/2 and 8/5/3 (notice how Bach adds the fifth to the 7/4/2 sonority)

- a rising melodic fourth ➎–➏–➐–➊ treble line.

To make these features clear(er), I made a rhythmic reduction:

In this case, however, ➎ doesn’t go directly to ➏ or via embellishments belonging to the triad of ① or the scale of C major but also via ♭➐, a feature we have not yet encountered. To indicate the ornamental/optional character of ♭➐ in this context, I have put it in parentheses in the reduction above.

Note how Bach applies the motivic and melodic construction of bar 1 to bars 2 and 3 as well:

- Just as ♭➐ appears on beat 4 of bar 1 as an embellishment of ➎, so ➊ appears on beat 4 of bar 2 as an embellishment of ➏.

- An implied new upper part appears in bar 3, which starts on ➋, ends on ➌ in bar 4a and is in fact a transposition of the upper part of bars 1–2b. (As such, ➍, which appears on beat 4 of bar 3, works as an embellishment of ➋.)

To further illustrate how ♭➐ in bar 1b and ➍ in bar 3b are optional and can therefore be replaced by another note without changing the essence of the progression, I have made three hypothetical versions of this Quiescenza without ♭➐:

Admittedly, these versions are less interesting than Bach’s original, but they are at least plausible and there is certainly nothing wrong with them.

The Quiescenza With ➊–(♭➐–)➏–➐–➊

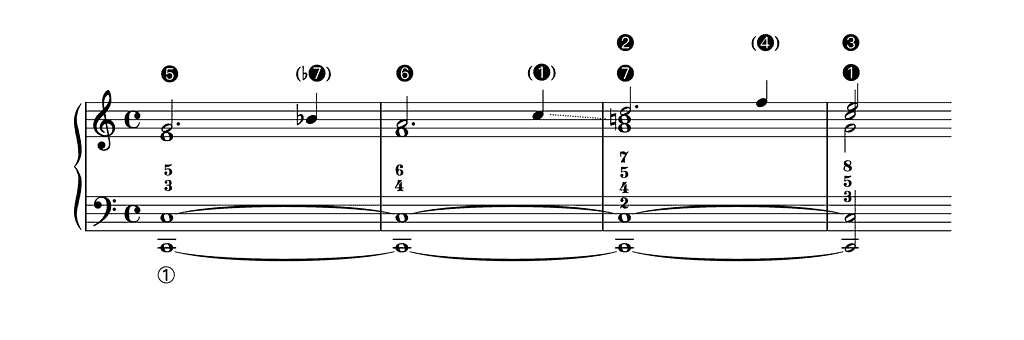

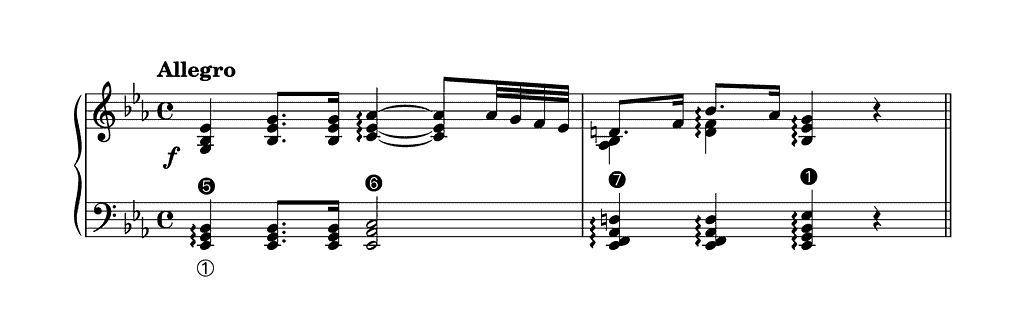

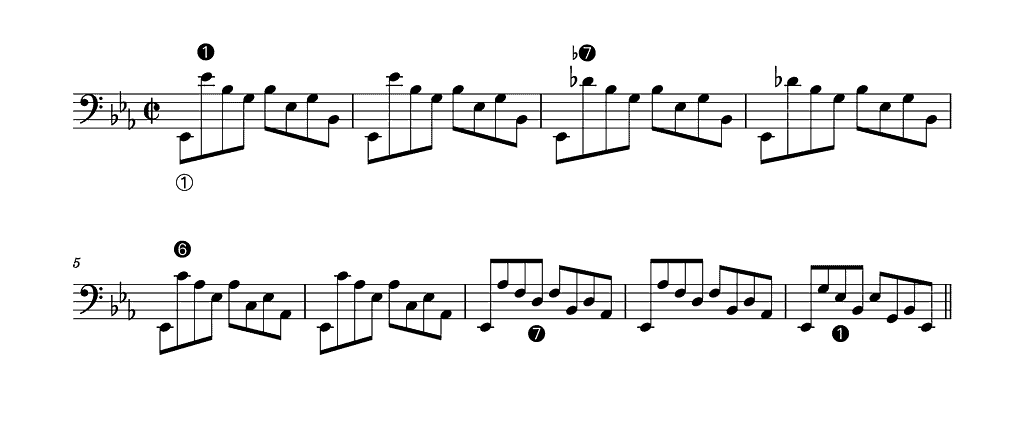

While the characteristic treble line of the Quiescenza begins (implicitly) on ➎ in most of the examples I have discussed so far, it can also begin on ➊, especially if it goes to ➏ via ♭➐, with a ➊–♭➐ snippet that is as long as the single ➎. In this case, ♭➐ acts as an embellishment of ➊, in the same way as when it is inserted between ➎ and ➏. (To point out the ornamental character of ♭➐, I have again put it in parentheses in the title.) Consider the following exemplar, which opens Joseph Haydn’s Keyboard Sonata in E flat major Hob. XVI:52:

In a texture with big chords instead of broken chords, note that

- the ➊–(♭➐)–➏–➐–➊ line occurs in the top voice of the left hand, with the treble line producing an alternative melody (we saw earlier that the characteristic melody of a Quiescenza does not only occur in the treble line)

- each structural sonority lasts two beats

- the ➊–♭➐ snippet is as long as any other structural melody note.

This Quiescenza with a ➊–(♭➐)–➏–➐–➊ line is again easily transformed into a Quiescenza without ♭➐. As you can see below, my hypothetical version presents a ➎–➏–➐–➊ melody in the top voice of the left hand:

The Quiescenza With ➊–♭➐–➏–➐–➊

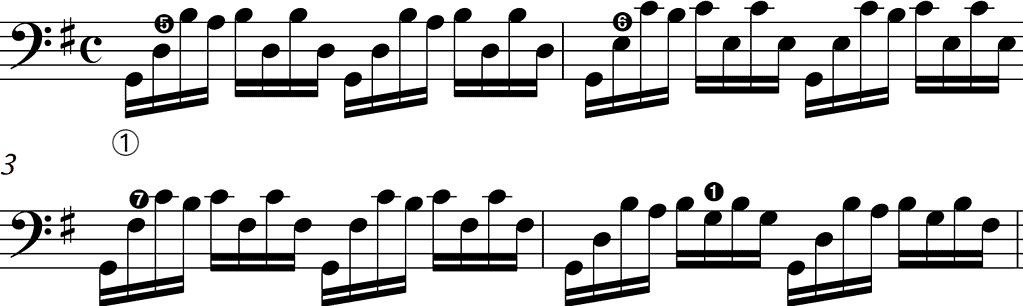

In the examples of a Quiescenza including ♭➐ we saw above, ♭➐ is integrated into the opening triad as an embellishment that doesn’t change the length of the first triad. However, the presence/introduction of ♭➐ can also lengthen a Quiescenza, with ♭➐ and the resulting dominant seventh chord lasting as long as any other structural note/sonority of the schema. (Note that “♭➐” isn’t in parentheses in the title of this section.) James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy call this type of melody “the ‘circular’ 8–♭7–6–7–8 (melodic) pattern” circumambulatio (Hepokoski and Darcy (2006), p. 91).) Consider first the following hypothetical version of the opening of the prelude from Bach’s Fourth Cello Suite in E flat major BWV1010:

In this version, the prelude opens with a Quiescenza with a ➎–➏–➐–➊ treble line whose final stage is reached after 6 bars. Let’s now look at Bach’s original:

Compared to my hypothetical version, the first two bars of the Quiescenza have ➊ instead of ➎ as structural melodic note, after which Bach inserts two additional bars with ♭➐ as structural melodic note. As a result,

- the 6/4 sonority, along with the following sonorities, is pushed back two bars

- the first eight bars are clearly grouped as a phrasal unit

- the final triad of the Quiescenza acts not only as an arrival point, but rather as the beginning of the next phrasal unit.

(Note that the penultimate and last structural melodic notes of the Quiescenza that opens the prelude from BWV1010 don’t appear in the treble line but in an inner voice, as is the case in the Quiescenza that opens BWV999, even when this is not a contrapuntal/melodic necessity.)

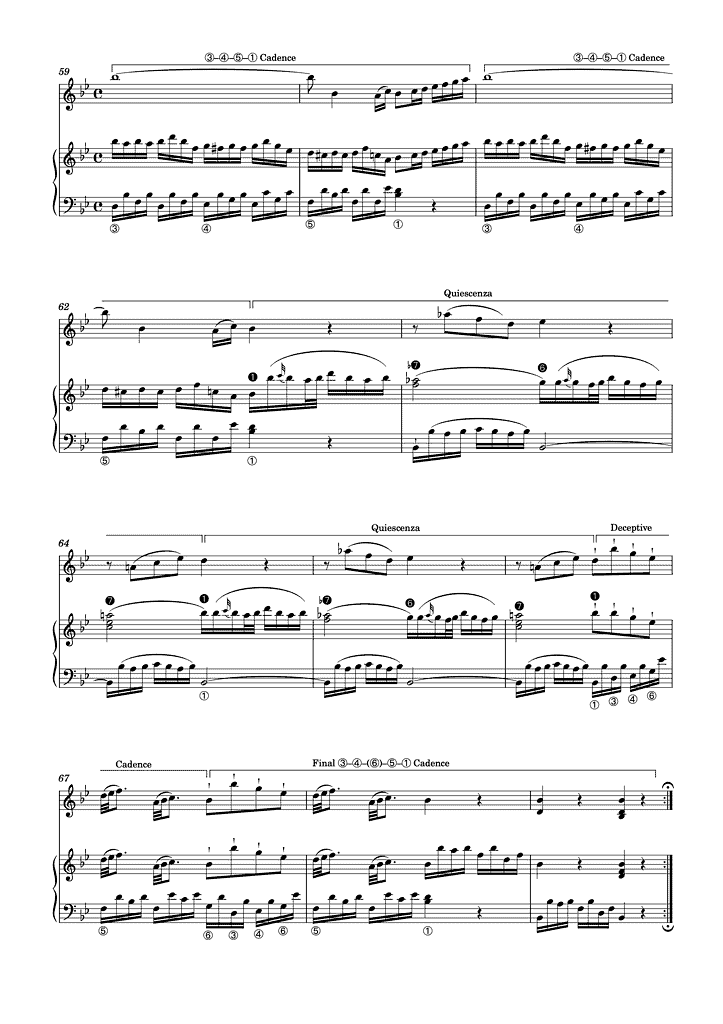

We often see this type of Quiescenza in which ♭➐ is as long as any other structural note of the schema when two Quiescenzas succeed each other in a closing passage, a type of pairing that Mozart was particularly fond of. Indeed, in a context where the length of segments and phrases is usually a product of 2, the Quiescenza with a ➊–♭➐–➏–➐–➊ treble line fits perfectly. As such, the final stage of the first exemplar coincides with the beginning of the second Quiescenza, the final stage of the second exemplar with the beginning of a new cadential progression or with the final metrically strong chord of a section or movement/composition. Let’s look at three such pairs of Quiescenzas by Mozart. The first is perhaps the earliest exemplar he wrote —he was just under eight when the piece in which it appears was published in Paris in 1763— and functions as a postcadential formula, heading towards the end of the movement:

(Whether the young Wolfgang or rather his father Leopold —at least in part— wrote these pieces is not the issue here. They are genuine galant pieces full of interest, whoever penned them.)

Like the two consecutive Quiescenzas in Cimarosa’s Keyboard Sonata in D major C30, those in KV8 are

- Embedded in such a way that they create a metrical shift. Indeed, from bar 62, we hear the actual barlines in the middle of the bar, a metrical shift that continues until the end of the sonata. (Note that the same passage, in F major and also metrically shifted, concludes the exposition of this sonata (not shown).)

- Followed by a deceptive cadence, which in turn is followed by a ③–④–⑤ cadence (as we have seen, C30 concludes with two more ③–④–⑤ consecutive cadences).

Notice also how the final stage of the first Quiescenza (bar 64b) coincides with the beginning of the second, and how the final stage of the second exemplar (bar 66b) also acts as the beginning of the deceptive cadence.

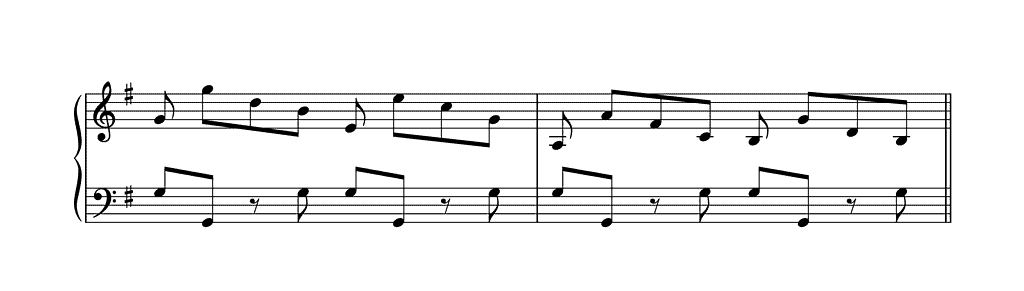

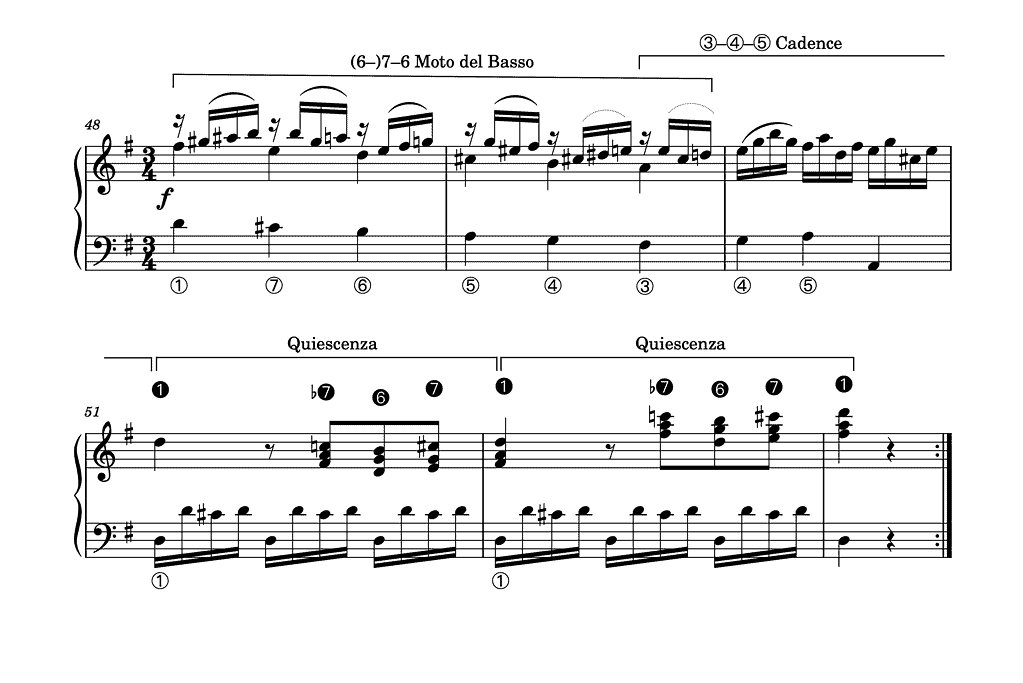

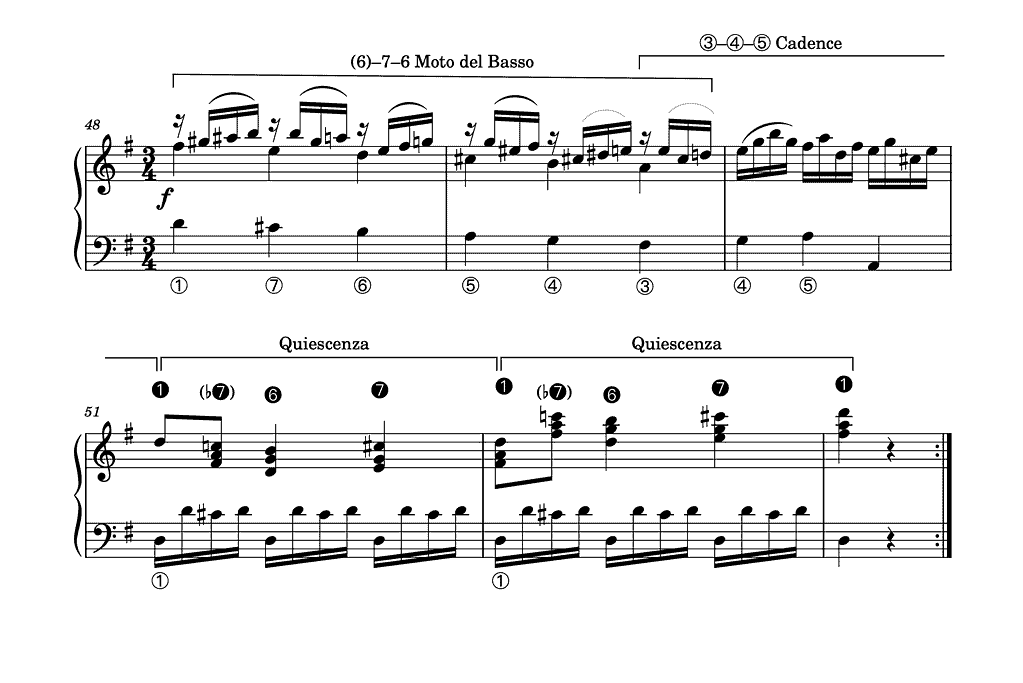

Another pair of Quiescenzas with a ➊–♭➐–➏–➐–➊ treble line concludes the exposition of the opening Allegro from Mozart’s Keyboard Sonata in G major KV283 (189h) composed in early 1775. Again, they are a postcadential formula of a clausala basizans, this time, however, not followed by other cadences but wrapping up this section.

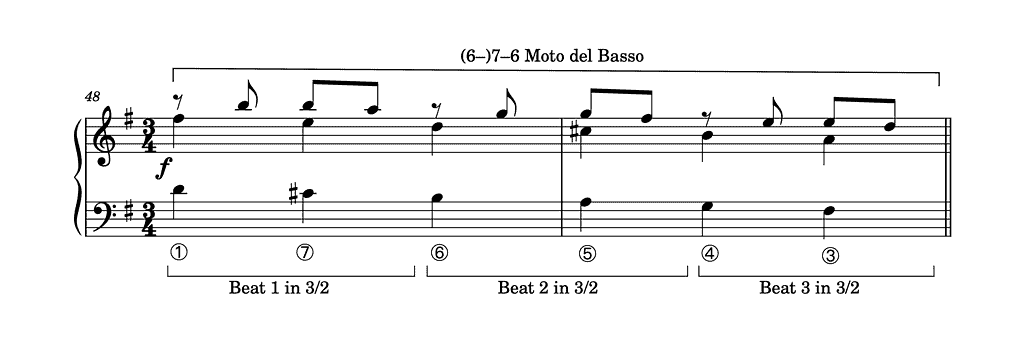

Metrically and rhythmically, the structural sonorities of these Quiescenzas are organized differently from those in the examples discussed above. Instead of lasting two beats or one or two bars, each structural sonority supporting the ♭➐–➏–➐ snippets of both Quiescenzas lasts only half a beat in a 3/4 time signature, occurring on the last three eighth notes of bars 51 and 52. As for the opening triads, however, they last a dotted quarter note (notated as a quarter note followed by an eighth-note rest). In a more regular, but rhythmically somewhat less exciting, version, the 6/4 sonority would be on beat 2, the 7/4/2 sonority on beat 3 —a rhythmic organization that reduces the metrical weight of ♭➐ (note each ♭➐ in parentheses):

Note

- the succession of a perfect and a diminished octave between the outer parts in bars 51 and 52 (D/D–C♯/C(♮)), which was not considered an issue in the galant style as the upper note of the diminished octave acts as a passing note or an appoggiatura.)

- the octave displacement in bar 52 after the opening triad in the right hand, making the second ♭➐–➏–➐–➊ snippet more prominent, and thus efficient as final gesture of the section.

Before moving on to the last example of this essay, just a few words about the moto del basso (bass motion) that comes just before the ③–④–⑤–① cadence, whose ① is prolonged by the pair of Quiescenzas. This moto offers an alternative setting for the rule of the octave, a setting that I have made a little more explicit in the following reduction:

While it is more usual to continue the chain of suspensions, Mozart decides to interrupt them every two beats, creating the metrical perception of one big 3/2 bar instead of two 3/4 bars.

(For more information on this moto del basso see my essay Diatonic Moti del Basso that Descend Stepwise.)

While the two previous examples of pairs of Quiescenzas occurred as a postcadential formula at the (near) end of the exposition or recapitulation of a sonata, the next one, also with a postcadential function, concludes the first couplet of the last movement, a rondeau, of Mozart’s Keyboard Sonata in B flat major KV281. (This sonata, together with KV283, belongs to a set of six sonatas Mozart wrote in Munich in early 1775.)

(The fermata is followed by a written-out Eingang (not shown), an improvisational passage that extends a triad or seventh chord on ⑤, typically used at the end of a couplet in a rondo to bring back the refrain.)

Again, this pair of Quiescenzas is preceded by a ③–④–⑤–① cadence. In this case, however, Mozart lingers on ④, which lasts two and a half bars (bars 36–38a), a gesture that Gjerdingen has labelled Indugio and that will be the topic of another essay. As for the Quiescenzas, they are a bit special because of the metrical position of ♭➐ and ➐. While they are usually metrically subordinate to the other structural notes of Quiescenzas that appear in closing passages, here Mozart promotes ♭➐ and ➐ by making them appear ‘too early’ and last ‘too long’, emphasizing them further with a fortepiano dynamic. Here follows the same passage made regularly, clearly without the wit of the original:

For more repertory examples of the Quiescenza with ♭➐ do check out the following videos by Seth Monahan and John Rice:

Further Reading (Selection)

Byros, Vasili. Trazom’s Wit: Communicative Strategies In a ‘Popular’ Yet ‘Difficult’ Sonata, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 10/2 (2013), p. 213–252.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Hepokoski, James and Darcy, Warren. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).