The Prinner is an incredibly versatile voice-leading pattern. I have already devoted three essays to this schema (The Traditional Prinner, Variants of the Prinner (Part 1) and Variants of the Prinner (Part 2): Sequential Prinners) but there is still much more to say about it.

In this essay, the third of four, I will deal with the following variants of the Prinner: the modulating Prinner, the incomplete Prinner and the canonic Prinner. I will also discuss how the Prinner can be mixed with other schemata (the Fonte and the Meyer).

The Modulating Prinner

As I already pointed out in my essay Variants of the Prinner (Part 1), a Prinner was not only used for a stepwise descending progression in the bass from ④ to ①. When the starting point is moved to ①, the schema allows modulation to the dominant key and is often used after the opening gestures of a composition in the main key. Any type of Prinner can be used for this purpose.

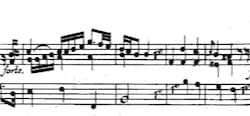

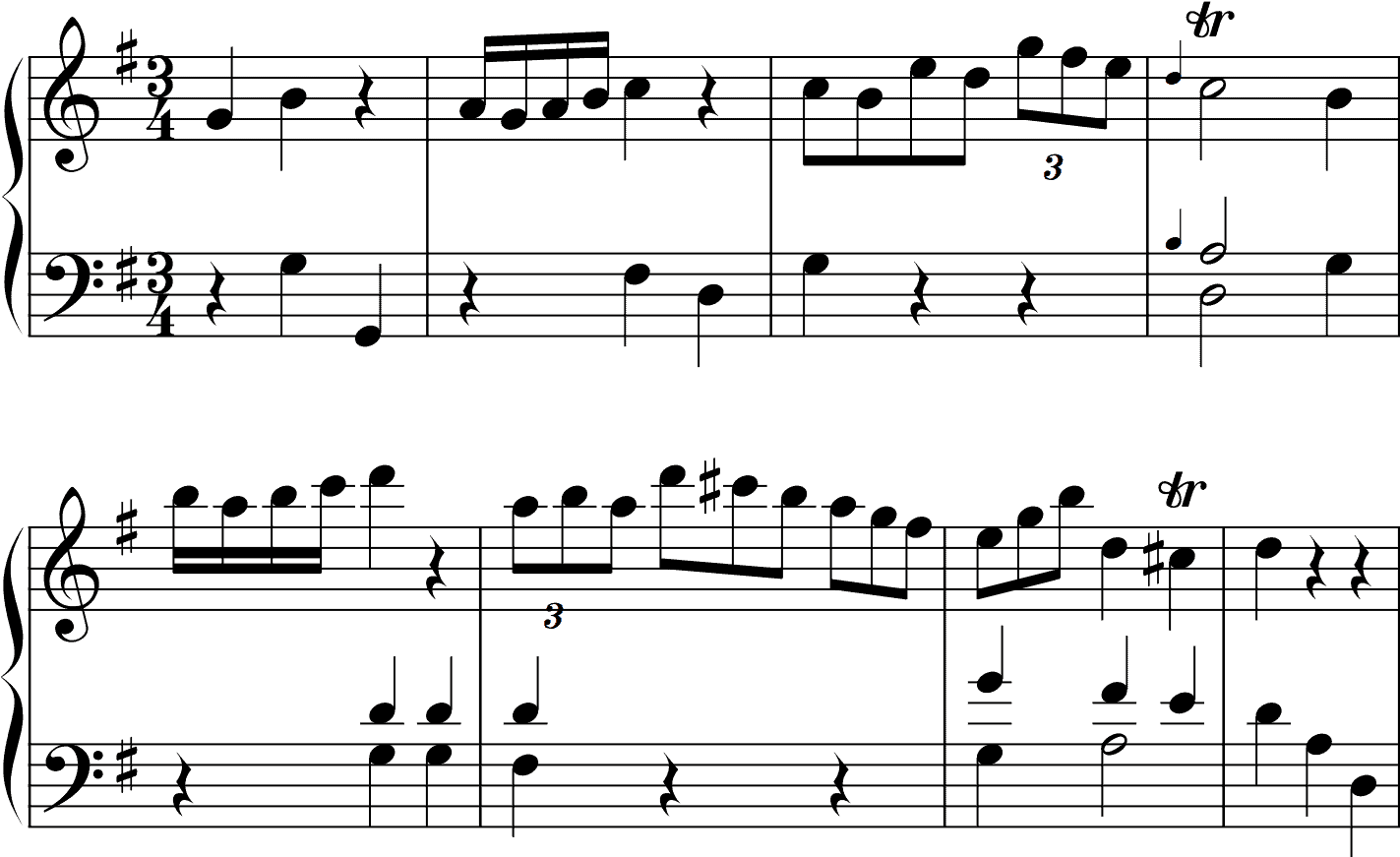

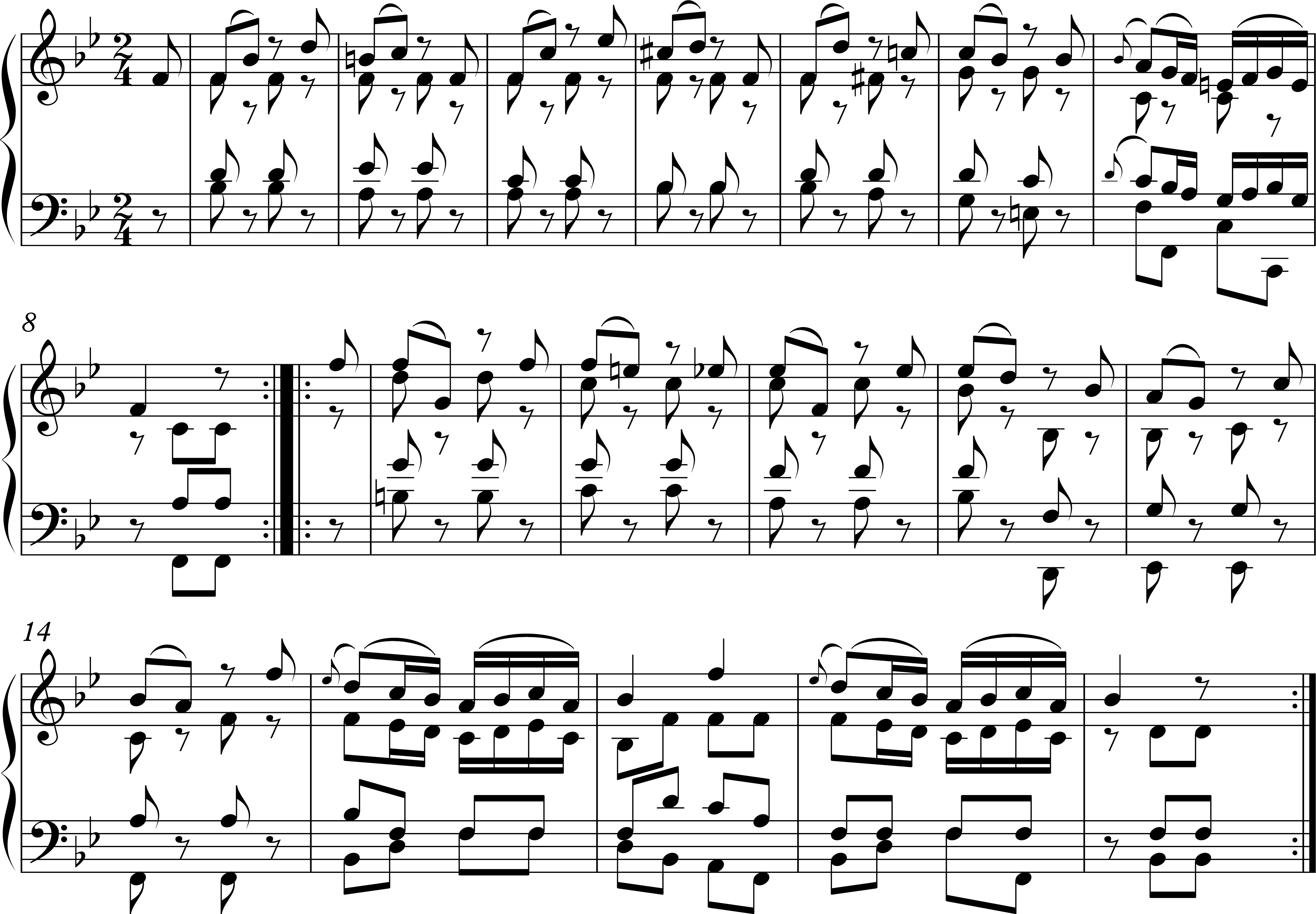

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788) starts the second movement of his sixth Württemberg Sonata with a six-bar phrase in B major that concludes with a ⑤–① cadence. Subsequently, B major is exchanged for F sharp major by means of a two-bar modulating Traditional Prinner without 7–6 suspension:

bars 1–9 (Modulating Prinner: bars 7–8),

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

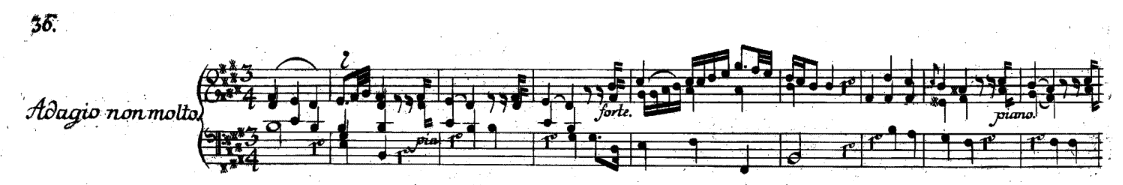

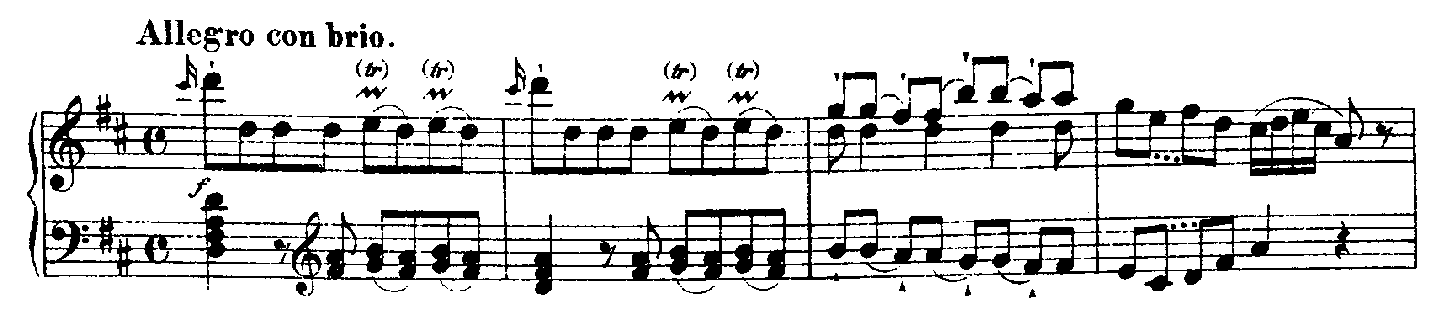

While the modulating Prinner in the example above is of rather modest proportions, that in the following example —the opening of a fast movement from a violin sonata by Wenceslaus Wodiczka (or Vodička; ca. 1715/1720–1774)— is more extensive:

Allegro ma non troppo, bars 1–9a (Modulating Prinner: bars 5–8a),

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

Wodiczka starts this Allegro ma non troppo with a combination of a Do-Re-Mi followed by a cadence, a combination he immediately repeats and varies. Hereafter, he writes a modulating Prinner with a ④–⑦–③–⑥–②–⑤–① bass line (in F major; bars 5–8a), extending to a half cadence in F major (bars 8b–9a; for more information on the Prinner with a ④–⑦–③–⑥–②–⑤–① bass line see my essay Variants Of The Prinner (Part 2): Sequential Prinners). Note how this modulating Prinner is both interesting and communicatively compelling. Compared to a non-modulating Prinner, the listener is presented with a ‘new’ note —E♮ in bar 5b— as part of an unexpected and expressive seventh chord already during the second half of its first stage.

The Incomplete Prinner

In his book Music in the Galant Style, Robert Gjerdingen explains that, especially in the second half of the eighteenth century, the first two stages of a Prinner are often isolated. The example below illustrates how the young Mozart writes an incomplete Prinner twice before giving the full version of this schema:

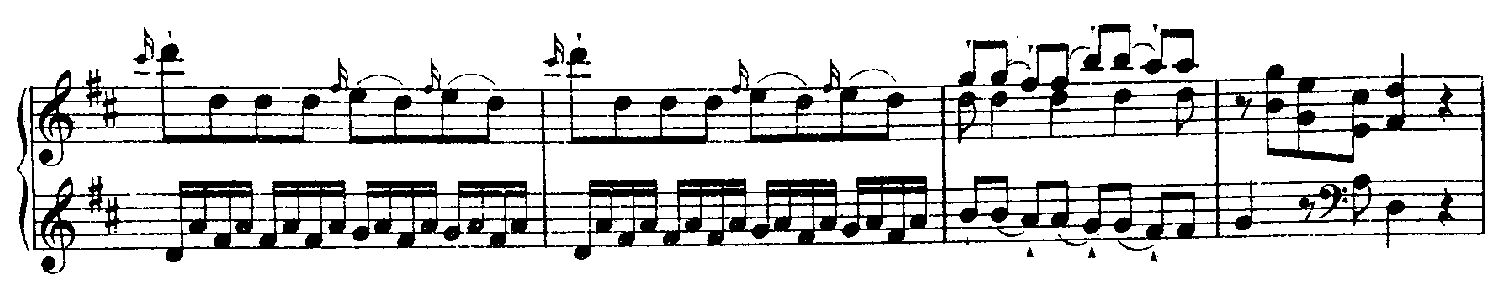

And the following example illustrates how Haydn gives only the first two stages of a modulating Prinner (bars 5–6) and then transforms this schema into a perfect ⑤–① cadence (bars 7–8):

(Incomplete Modulating Prinner: bars 5–6)

The Canonic Prinner

The canonic Prinner —another term by Gjerdingen (Gjerdingen: 2007, 54)— is a type of Prinner that is expanded by two stages before its regular first stage. While the bass of a regular Prinner usually starts on ④, the bass of a canonic Prinner starts on ⑥ to begin its stepwise descent. Since the ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent starts on the third stage, this extension creates a short canon between the outer voices.

Note that above ⑥–⑤ in the bass, the upper voice usually produces ➍–➌. That way, a second (suggestion of a) canon arises, the bass producing ④–③ during stages 3 and 4. The visual aspect of the voice exchange in the outer parts during the first four stages has inspired Nicole DiPaolo to label this type of Prinner the Spinny Prinner.

Just as a Prinner can be incomplete, a canonic Prinner can be too. In the example above, the canonic Prinner extends to a half cadence in bar 4. From bar 5 on, Haydn repeats (and varies) this phrase. This second phrase, however, ends with a perfect ⑤–① cadence preceded by an incomplete canonic Prinner.

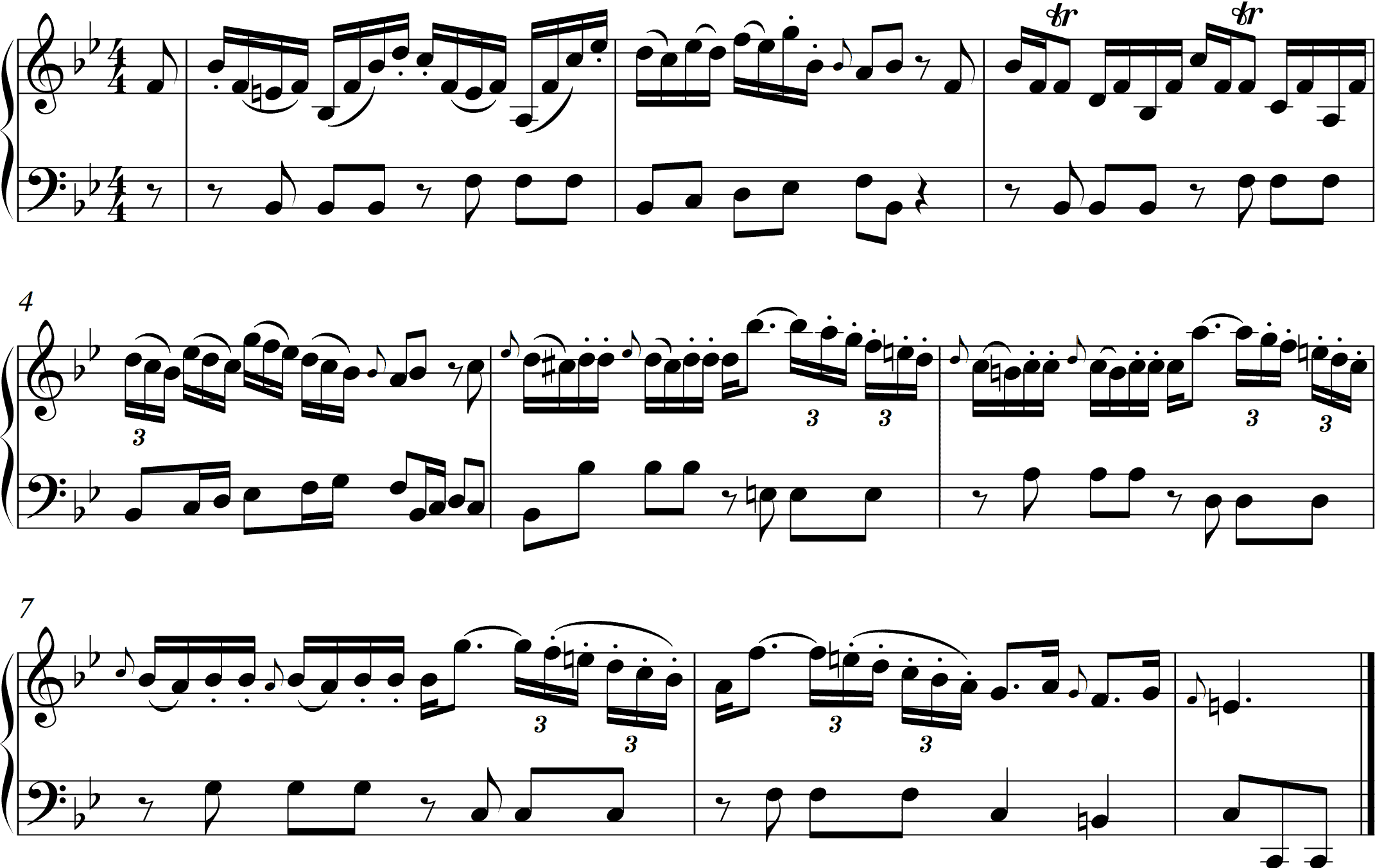

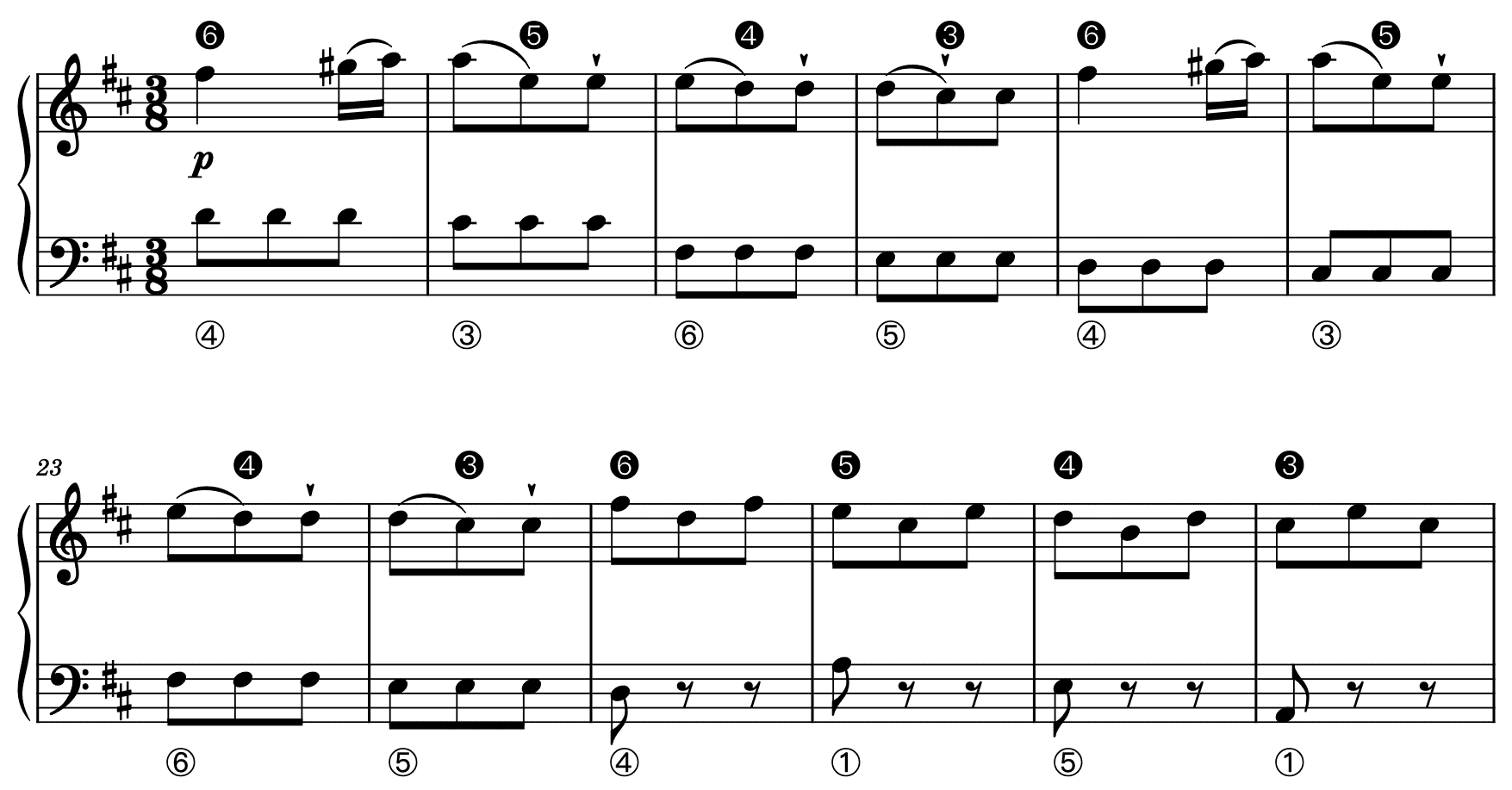

When the voice exchange in the outer parts during the first four stages is repeated, a canonic Prinner loop arises. The fragment below —in the key of A major— seems to start as a regular Prinner with ➏–➎ in the top voice and ④–③ in the bass. While the upper voice continues its regular ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent —the top voice actually produces three such consecutive descents, the bass in bar 19 (the third bar in the fragment) does not progress to ② but to ⑥. This point in the bass turns out to be the start of the first of two consecutive ⑥–⑤–④–③ descents, the second of which lacks the last note. The reason the second ⑥–⑤–④–③ descent is incomplete is that the third ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent, which starts in bar 25, breaks with the loop and is instead set as a Prinner with a ④–①–⑤–① bass line. (For more information on this type of Prinner see my essay Variants of the Prinner (Part 1).)

Ars Combinatoria

Gjerdingen argues that “the fluid mixing and matching of schemata would seem to exemplify perfectly the ars combinatoria [or ‘art of combinations’] … this was a philosophical tradition cited by Riepel and other eighteenth-century musicians” (Gjerdingen, 2007: 99 & 115).

The Prinner With a Nod to an Embedded Fonte

In my essay Variants of the Prinner (Part 2): Sequential Prinners, we already saw how a schema could be embedded within a larger schema. I illustrated how the presence of ①♯ or ➊♯ in a circle-of-fifths Prinner could hint at an embedded Fonte within a larger Prinner. Of course, this alteration, and the suggestion of an embedded Fonte, can also occur within a shorter Prinner with a ④–③–②–(⑤ or ⑦–)① bass line.

Consider the following fragment, which is the theme from a theme and variations by Dittersdorf.

(Modulating Prinner With a Nod to an Embedded Fonte: bars 5–7a)

The piece starts with a four-bar chromatic Do-Re-Re-Mi after which a modulating Prinner in bars 5–7a takes the music to F major, confirmed by the ⑤–① cadence in bars 7b–8. As its second stage (bar 5b), however, this modulating Prinner does not present a sixth chord with an F(♮) but a 6/4/3 chord with an F♯. That way, there is a suggestion of G minor before the music goes to F major, that is, the tonal path of a Fonte in F major. While a Fonte normally presents the same type of cadence —usually a clausula cantizans— twice, Dittersdorf here opts for a clausula tenorizans in G minor followed by a clausula cantizans in F major. Note that these compositional decisions result in a bass line with the standard ④–③–②–① outline of a Prinner (from the perspective of F major). Note also that Dittersdorf could have pushed the Prinner more into the corner of the Fonte by putting the F♯ in the bass instead of the second violin on the second beat of bar 5.

The Prinner With a Nod to an Embedded Meyer

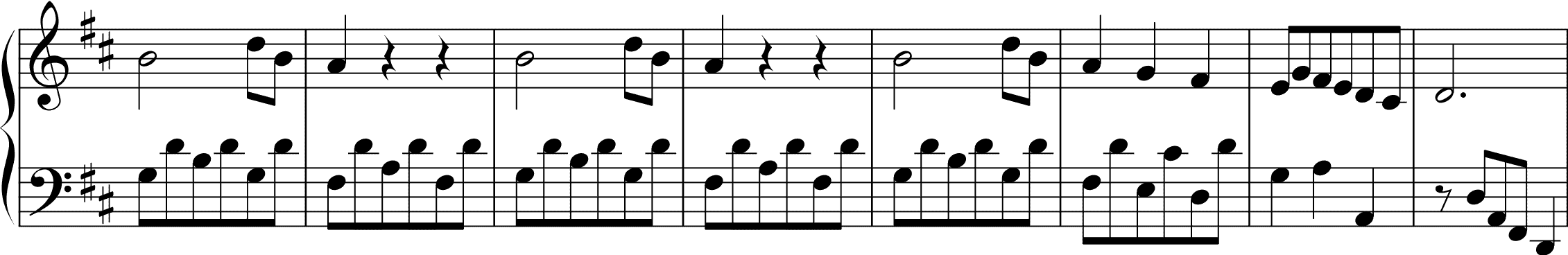

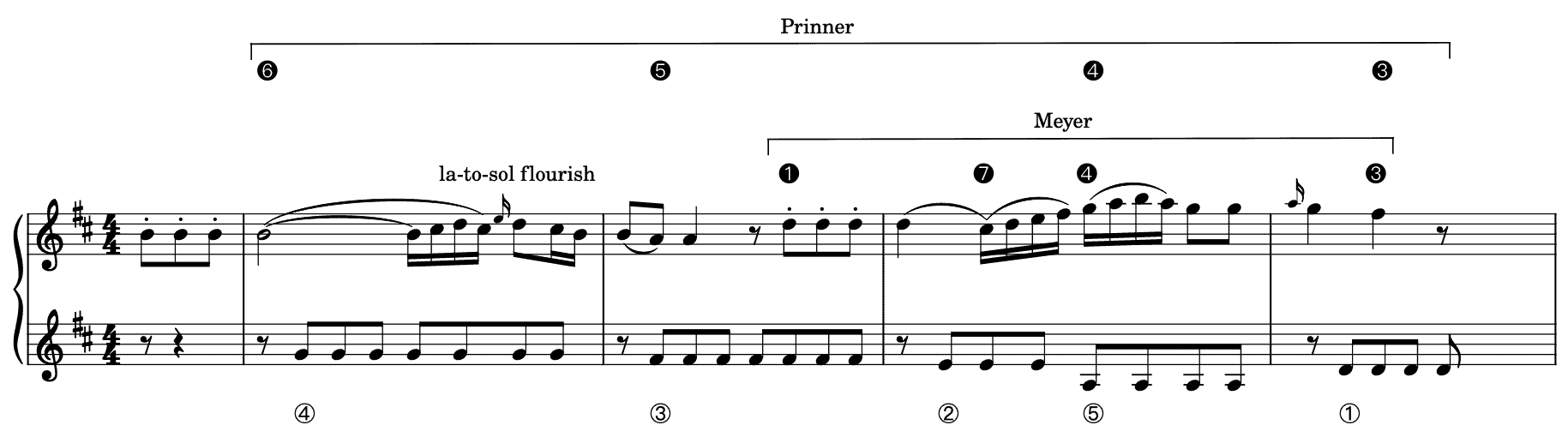

In his book Music in the Galant Style, Gjerdingen gives a beautiful example of Prinner with a nod to an embedded Meyer (Gjerdingen, 2007: 114):

(The Meyer, named by Gjerdingen after Leonard B. Meyer who first pointed out the importance of this schema in the eighteenth century, is characterized in its standard form by a ➊–➐–➍–➌ melody and a ①–②–⑤–① or ①–②–⑦–① bass. I will explore the Meyer in a yet-to-be-published essay.)

Gjerdingen further notes that “the ‘la-to-sol flourish’ marked on [the] example [above] was an ornamental motif closely associated with Prinners” (Gjerdingen, 2007: 114).

What Gjerdingen does not mention about this Prinner, however, is that it is one of the rare exemplars used as a proposta, that is, as an opening gesture. (This Prinner begins an allegro after an adagio introduction.)

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Prinner, Johann Jacob. Musicalischer Schlissl (1677).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — II. Grundregeln zur Tonordnung (1755).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — III. Gründliche Erklärung der Tonordnung (1757).

Secondary Sources

Caplin, William E. Harmony and Cadence in Gjerdingen’s “Prinner”, in: What Is a Cadence? Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, ed. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015), 17–57.

Demeyere, Ewald . On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207-229.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).