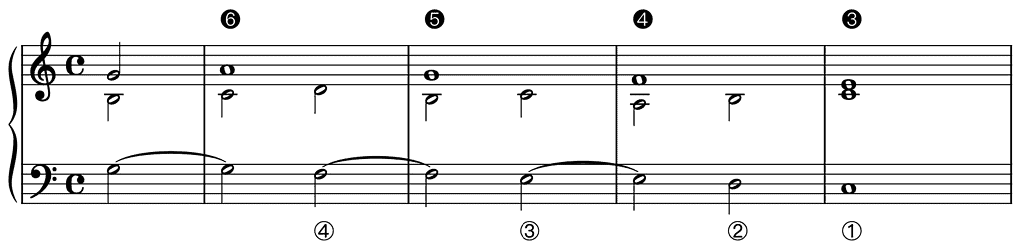

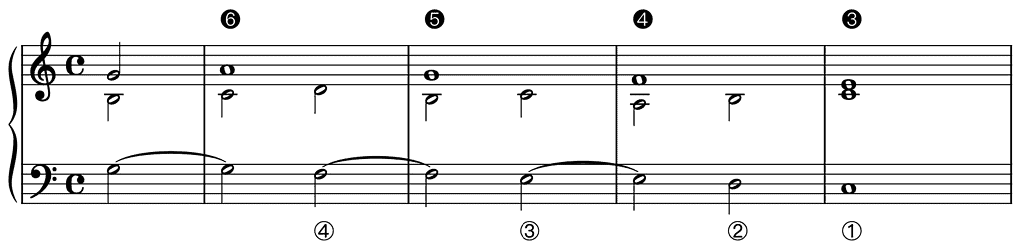

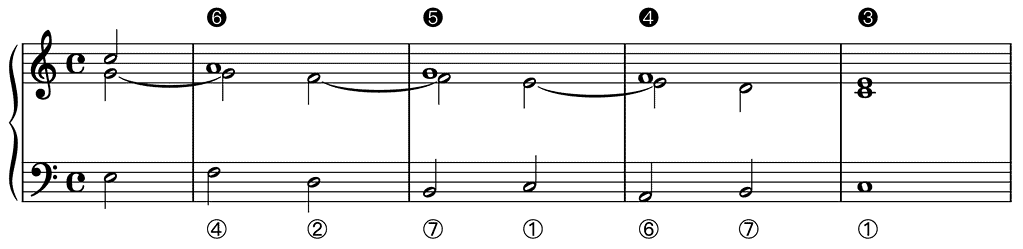

The two-part Prinner with its ➏–➎–➍–➌ melody and ④–③–②–① bass line holds great potential as a sequential progression thanks to its voice leading in parallel thirds. As can be seen in my essays The Traditional Prinner and Variants of the Prinner (Part 1), however, the presence of a third voice very often undermines that potential. On the other hand, Sequential Prinners do realize that potential, at least in part.

In this essay, the second of four, I deal with sequential Prinners. First, I will elaborate on circle-of-fifths Prinners, which come in many forms. Secondly, I will explain two types of Fauxbourdon Prinners, one consisting of parallel sixths chords and one with 7–6 suspensions.

Circle-of-Fifths Prinners

The concept of inserting an extra ⑤ or ⑦ in between ② and ① —you can observe a number of those variants in my essay Variants of the Prinner (Part 1)— can be applied to the entire Prinner. That way, a sequential pattern arises commonly known today as a circle of fifths, of which several variants were common in the 18th century. Circle-of-fifths Prinners offer a musically interesting solution for long Prinners with a harmonic rhythm that otherwise may be too slow.

The Prinner With a ④–⑦–③–⑥–②–⑤–① Bass Line

In this variant, the addition of ⑤ to stage 3 is transposed forward twice. That way, a bass pattern arises that partimentisti (practitioners of partimento) called falling by fifths and rising by fourths (or rising by fourths and falling by fifths).

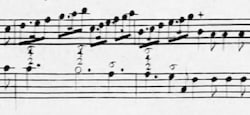

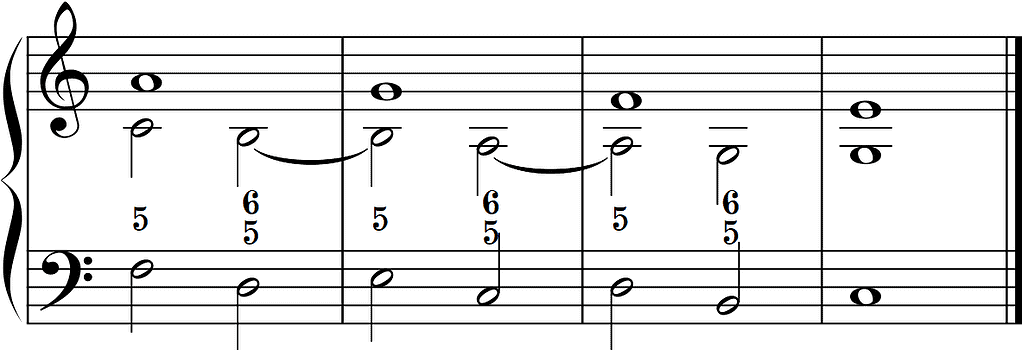

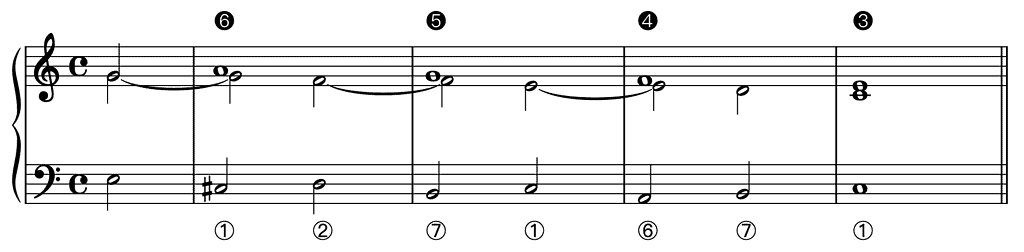

As the example above illustrates, two settings are usual:

- with alternating triads and seventh chords

- with seventh chords only (except for the first and last chords, which are triads).

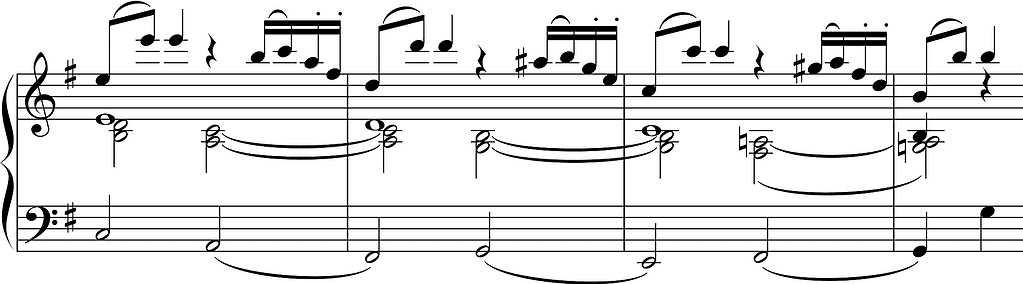

This is a repertoire example —the start of a courante by George Frideric Handel (1685–1759)— of the setting with alternating triads and seventh chords:

Note how this courante opens with a Galant Romanesca that proves to be the start of a Do-Re-Mi opening gambit (more on these schemata in other essays).

The Prinner With a ④–③–⑥–②–⑤–① Bass Line

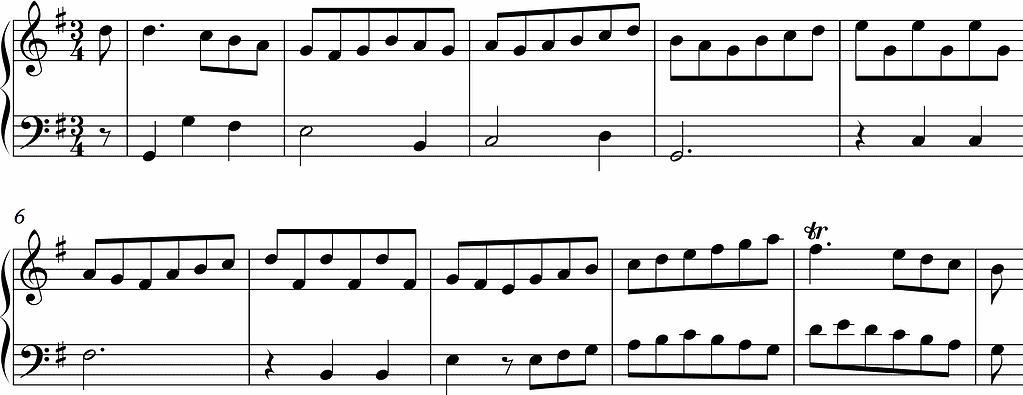

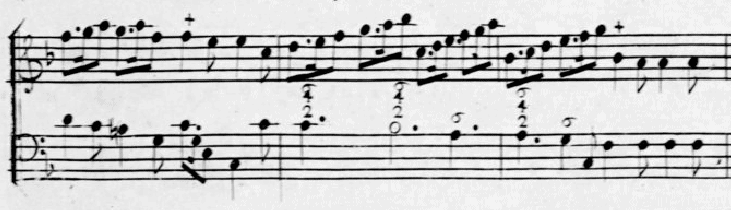

Quite often, the circle of fifths in the context of a Prinner starts only from stage 2. In this case, an inserted ⑦ in between ④ and ③ is absent. The following example — the start from an allegro for violin and continuo by Francesco Geminiani (1678–1762)— shows such a Prinner. After a brief opening gambit establishing D major, a Prinner with a ④–③–⑥–②–⑤–① bass line starts on the upbeat to beat 3 of the opening bar.

Allegro, bars 1–2,

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

Note how the skeletal notes of the two stepwise descents are clearly discernible in the violin as well as in the continuo.

In the example above, only one chord/sonority occurs during the opening stage of the Prinner. This type of Prinner without an inserted ⑦ in between ④ and ③, however, can still have two different chords/sonorities above the opening ④. Consider the following example, a two-part start of a trio sonata by Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713). (It is hard to overestimate the influence Corelli, a Roman violinist and composer, exerted on musicians of his and the next generations, not in the least in the realm of schematic thinking.)

Allegro, bars 1–2, ed. F. Chrysander (Sonate Da Chiesa A Tre Opera Terza, London: Augener & Co., 1888–91, public domain, available on https://imslp.org

A Prinner starts on beat 4 of the opening bar. But instead of simply setting that beat with a triad, Corelli calls for a triad followed by a sixth chord. That way, the latter allows the preparation of the seventh on ③. (In the example by Geminiani, however, stage 1 was set as a triad, the beginning of stage 2 as a sixth chord.)

The Prinner With a ④–②–③–①–②–⑦–① Bass Line

In this variant, the addition of ⑦ to stage 3 is transposed forward twice. That way, a bass pattern arises that partimentisti called falling by thirds and rising by seconds. This pattern functions as a derivative of the circle of fifths in which every second chord is a 6/5 instead of a seventh chord.

A repertoire example of this type of Prinner —a fragment from an allegro for violin and continuo by Pierre Gaviniés (1728–1800)— can be seen and heard below.

Allegro, bars 1–19,

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

This allegro starts with establishing A major in bar 1. In bars 2–3, an incomplete Prinner occurs, consisting of only the first two stages (I will devote more space to this type of Prinner in part 3 of this series on variants of the Prinner). This incomplete Prinner is immediately followed by a complete Prinner in bars 4–6. Hereafter, the music changes abruptly from A major to E major with a four-bar phrase establishing E major (bars 7–10). This phrase is followed by another Prinner, starting in bar 11, this time a Prinner with a ④–②–③–①–②–⑦–① bass line. Note that the setting of this Prinner is enriched here with a fourth voice including suspensions of the ninths on the first beat of every bar. And this Prinner leads up to a half cadence in E major (bars 14–16).

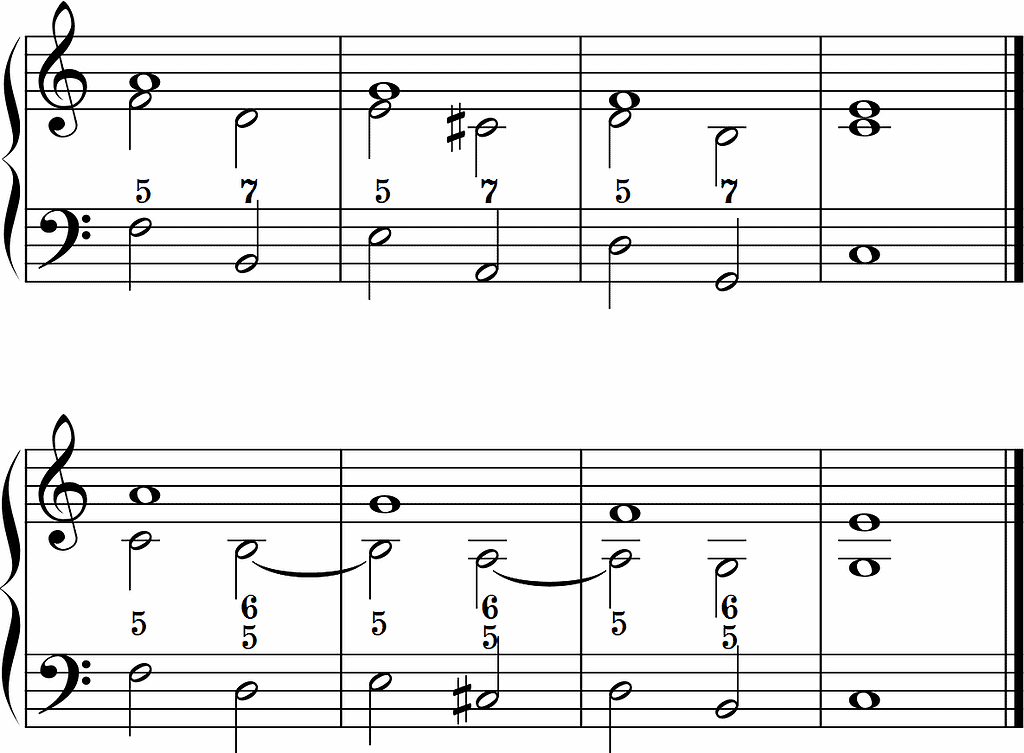

The Circle-of-Fifths Prinner With a Shifted ④–③–②–① Bass Line and 2–3 Suspensions

Each skeletal note of the bass line of the (Traditional) Prinner can be introduced with a suspension set as a 4/2 chord. That way, 2–3 suspensions occur between the bass and the ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent during the first three stages of the Prinner. In this case, the chord/sonority preceding the circle-of-fifths Prinner with a shifted ④–③–②–① bass line is most often a triad on ⑤, allowing a smooth preparation of the first suspension.

IJzerman calls this sequential technique the Tied Bass for obvious reasons (IJzerman, 2018: 48–51).

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710–1736) uses this type of Prinner, amongst others, in Serpina’s aria A Serpina penserete of his famous intermezzo La serva padrona. While the key of the aria is B flat major, the key of the fragment below is F major. As we already saw a number of times, this Prinner leads up to a half cadence as well.

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

Let us have a look at the harmonic rhythm of this passage. This section of the aria is written in a 3/8 time signature. Pergolesi chooses to write the resolutions of the 4/2 chords on the second eighth note of each bar of the Prinner. In bars 15 and 16, this resolution chord is extended on the third beat, resulting in a harmonic rhythm of an eighth note followed by a quarter note. Also in bar 17, the resolution of the 4/2 chord occurs on the second beat. Yet, while bars 15 and 16 each represent one stage of the Prinner, bar 17 contains not only stage 3 (beats 1 and 2) but also stage 4 (beat 3).

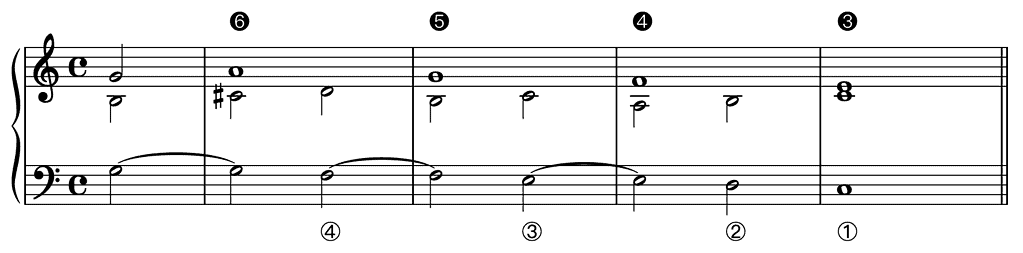

The Circle-of-Fifths Prinner With a Shifted ④–③–②–① Bass Line and 2–6 Suspensions

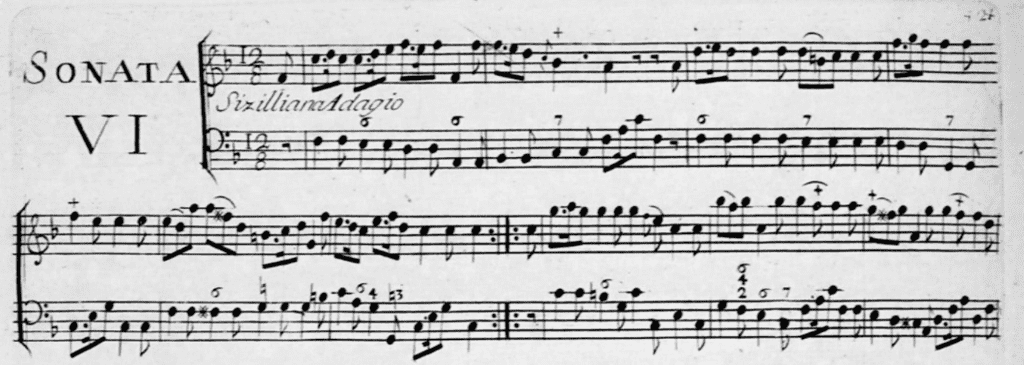

In the following example, an excerpt from an adagio for violin and continuo by Wenceslaus Wodiczka (1715/1720–1774), the harmonic rhythm of the circle-of-fifths Prinner with a shifted ④–③–②–① bass line stays regular until the conclusion of the schema. Each stage lasts half a bar, containing one sonority per beat.

Sizilliana [sic] Adagio, bars 15–17,

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

(The first edition of Wodiczka’s opus 1 contains a number of mistakes. In the fragment above, beat 2 of bar 16 has been figured with “6/4/2” while it should have been figured with “6” and “6/4/2” should have occurred above beat 3.)

The melodic outline of this Prinner, however, is different. While the skeletal notes of the ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent fall again on the start of each stage of the Prinner, the note in the violin on the weak beat of each stage is a fourth higher than the preceding skeletal note of the ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent. That way, the 2–3 suspensions between the bass and the violin become 2–6 suspensions.

The Prinner With a ①–②–⑦–①–⑥–⑦–① Bass Line and 2–3 Suspensions

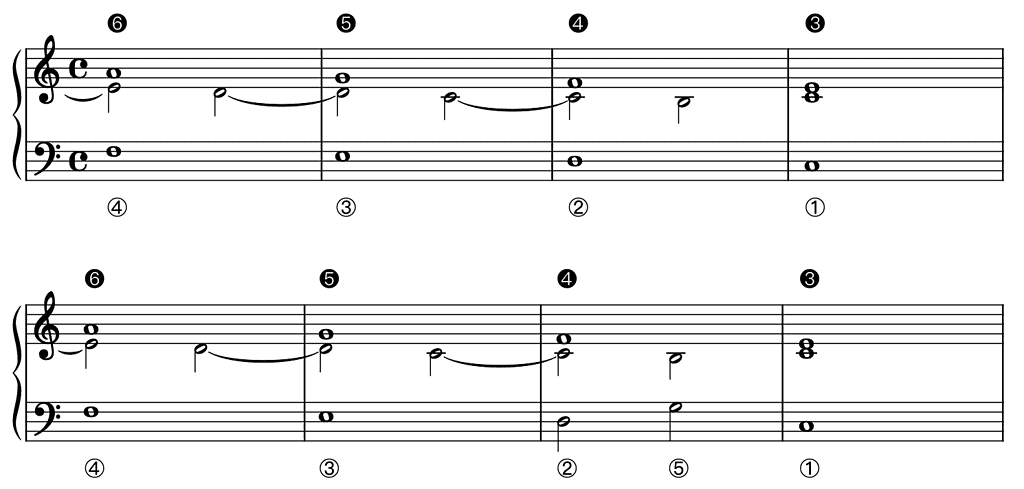

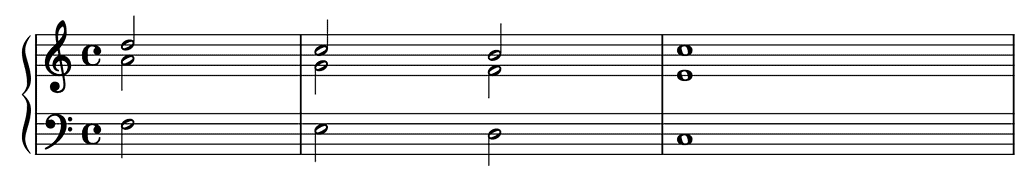

Reconsider the following example of a circle-of-fifths Prinner with a shifted ④–③–②–① bass line:

When the middle voice and the bass are swapped, another variant is generated in which the 2–3 suspension chain occurs in the middle voice:

The Prinner With a ④–②–⑦–①–⑥–⑦–① Bass Line and 2–3 Suspensions

A variant of this type of Prinner has ④ in the bass to start the schema:

The latter variant occurs for instance in a string quintet by the Austrian composer and violinist Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739–1799):

Circle-of-Fifths Prinners With a Nod to an Embedded Fonte

The very concept of a circle of fifths is that it allows tonicization of other scale steps than the first. When such tonicization occurs in the context of a circle-of-fifths Prinner in a major key, it usually tonicizes the supertonic. (In a minor key, the mediant is tonicized in the context of a circle-of-fifths Prinner.) Since this progression is repeated one step lower, both progressions together might be interpreted as what Joseph Riepel (1709–1782), chapel master in Regensburg, could have described as a Fonte (Italian for well), albeit with an atypical structural application.

(Riepel describes the Fonte as a pattern that is often used as the opening figure of the second half of movements in a major key. He defines the Fonte as having two segments that are each other’s transpositions. The first segment is set in the minor key of the supertonic (e.g. D minor when the main key of the piece is C major). The second segment is in the main key. The content of each segment is typically a clausula cantizans, although any type of cadence can be used.)

Below you find two examples of a circle-of-fifths Prinner with a nod to an embedded Fonte at the end of the circle-of-fifths Prinner:

And these are two examples of a circle-of-fifths Prinner with a nod to an embedded Fonte at the start of the circle-of-fifths Prinner:

Tip for Practising

Make sure to practice all the circle-of-fifths Prinners with a nod to an embedded Fonte.

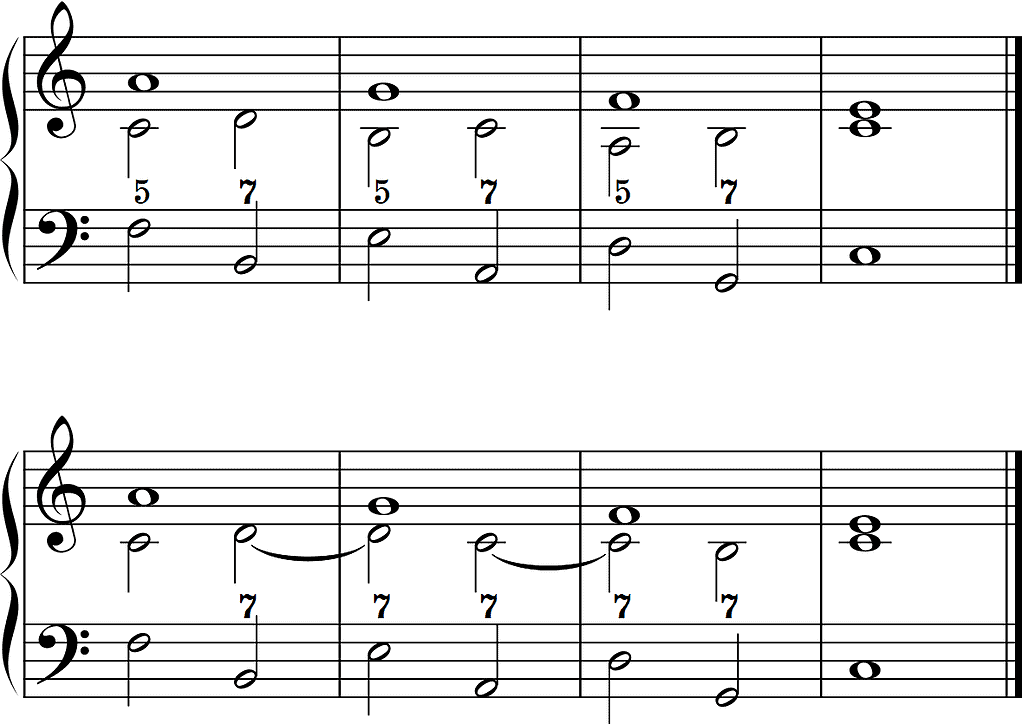

The Prinner With 7–6 Suspensions (The 7–6 Fauxbourdon Prinner)

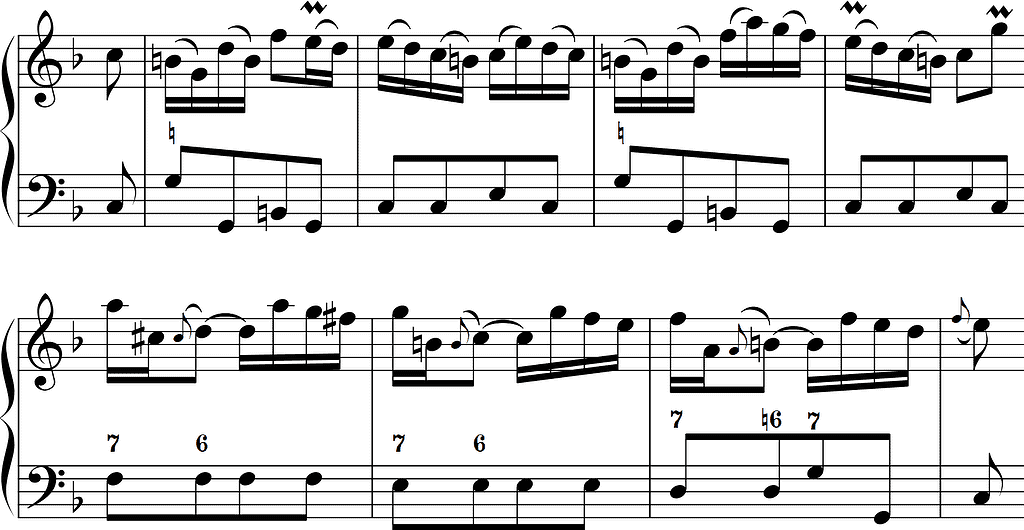

A variant of the Prinner akin to the circle-of-fifths Prinners is the one in which the first three, or the first two stages in the case the third stage has a ②–⑤ snippet, are set with 7–6 suspensions. In this case, the chord/sonority preceding the Prinner with 7–6 suspensions is most often a triad on ①, allowing a smooth preparation of the first suspension.

IJzerman calls this sequential technique the 7–6 Fauxbourdon since it “can be regarded as an embellished Fauxbourdon” (IJzerman, 2018: 37; I will deal with the regular Fauxbourdon below).

Tips for Practising

One can easily make these Prinners with 7–6 suspensions into a Prinner with a ④–⑦–③–⑥–②–⑤–① bass line. To this end, just transform the whole notes in the bass of the first three stages into two half notes, the first being the skeletal note, the second a fourth above the skeletal note. (This is already the case in the third bar of the second system in the example above.) And make sure to practice the variants with 7–6 suspensions in two positions for the right hand, that is, with the ➏–➎–➍–➌ descent in the top voice (as shown in the example above) and with the part with the 7–6 suspensions in the top voice (not shown).

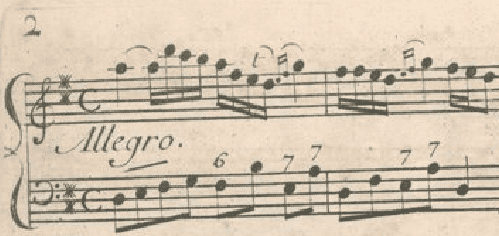

The following excerpt from a vivace for violin and continuo by Giovanni Battista Somis (1686–1763) contains such a Prinner with 7–6 suspensions. While the key of this movement is F major, the key of the fragment below is C major.

Vivace, bars 22–29a (Prinner with 7–6 suspensions: bars 26–29a),

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

Note how the composer personalizes this schema by, among other things, a different harmonic rhythm (the sevenths last only an eighth note) and an anticipated leading note before the penultimate chord of the Prinner.

In the next example, which shows the beginning of the violin sonata in F major by Wodiczka I already referred too, this type of Prinner is used to modulate from F major to C major and does not include a 7–6 suspension during the first stage, which is set instead as a sixth chord.

Sizilliana [sic] Adagio, bars 1–9 (Modulating Prinner with 7–6 suspensions: bars 3–4),

public domain, available on https://imslp.org

(As I already mentioned, the first edition of Wodiczka’s opus 1 contains a number of mistakes. In the fragment above, “6” is lacking above beat 4 of bar 3 and a seventh chord is probably intended on the downbeat of bar 4.)

The Prinner Set With Sixth Chords (The Fauxbourdon Prinner)

This variant of the Prinner is a simpler version of the previous one, omitting the onbeat sevenths and setting the first three stages as sixth chords. This technique is commonly called Fauxbourdon today (see, amongst others, IJzerman, 2018: 30).

In this case, it is important that the vertical parallel sixths occur in the top voice, the vertical parallel thirds in the middle voice. When both voices are swapped, they produce parallel fifths between them.

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Prinner, Johann Jacob. Musicalischer Schlissl (1677).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — II. Grundregeln zur Tonordnung (1755).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — III. Gründliche Erklärung der Tonordnung (1757).

Secondary Sources

Caplin, William E. Harmony and Cadence in Gjerdingen’s “Prinner”, in: What Is a Cadence? Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, ed. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2015), 17–57.

Demeyere, Ewald . On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207-229.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).