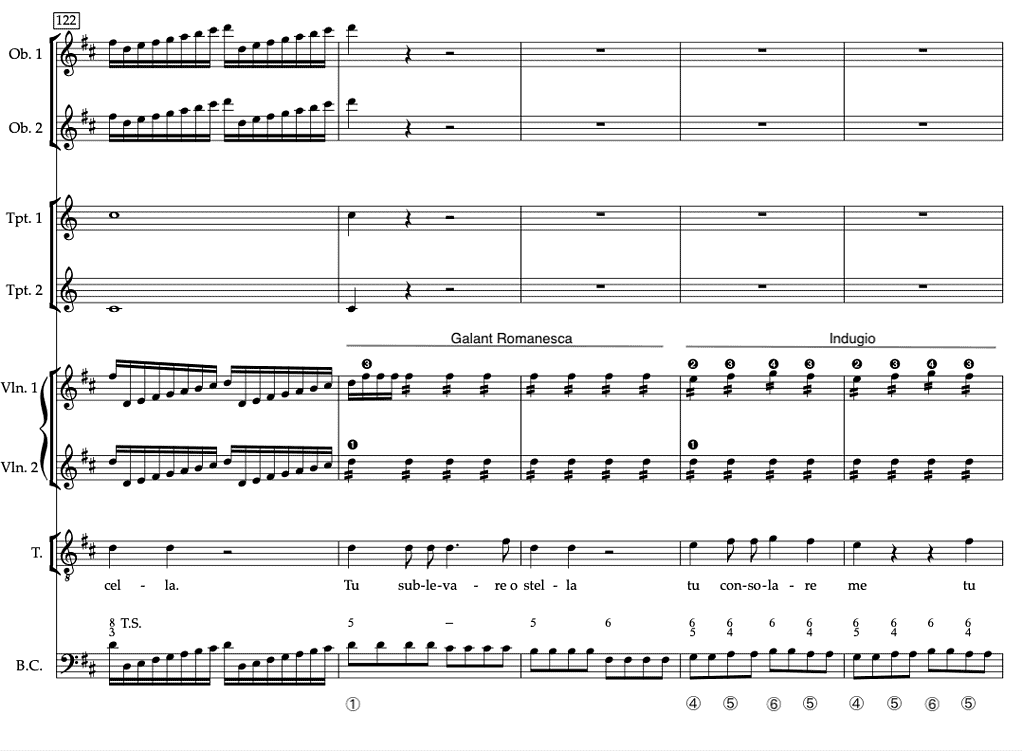

In my essay The Indugio (Part 1), I explain that an Indugio —a term by Gjerdingen— is essentially a pedal point on ④, set with a sixth chord or a 6/5 chord used to delay the conclusion of a cadence. In this essay, I address a variant that Gjerdingen also discusses but didn’t give an individual name. To distinguish that variant —with a specific voice leading— from the other types of Indugio, I add the adjective ‘circular’ to the label.

In a circular Indugio, the bass goes stepwise from ④ to ⑥ and back to ④, the treble in parallel sixths from ➋ to ➍ and back to ➋, while the middle part has a pedal point on ➊. As with any Indugio, a circular Indugio is also used to delay the conclusion of a cadence.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in an upper part (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Note further that ‘Bar 1a’ refers to the first half of bar 1, ‘bar 1b’ to its second half.

Features of the Circular Indugio

The circular Indugio is essentially a three-part schema characterized by:

- a circular rotation of a ④–⑤–⑥–⑤–④–… pattern in the bass, with ④ being metrically the strongest

- a circular rotation of a ➋–➌–➍–➌–➋–… pattern in the upper voice in parallel sixths with the bass, with ➋ being metrically the strongest

- a pedal note on ➊ in the middle voice.

This voicing leading results in:

- a 6/5 chord on ④

- a passing 6/4 chord on ⑤

- a sixth chord on ⑥.

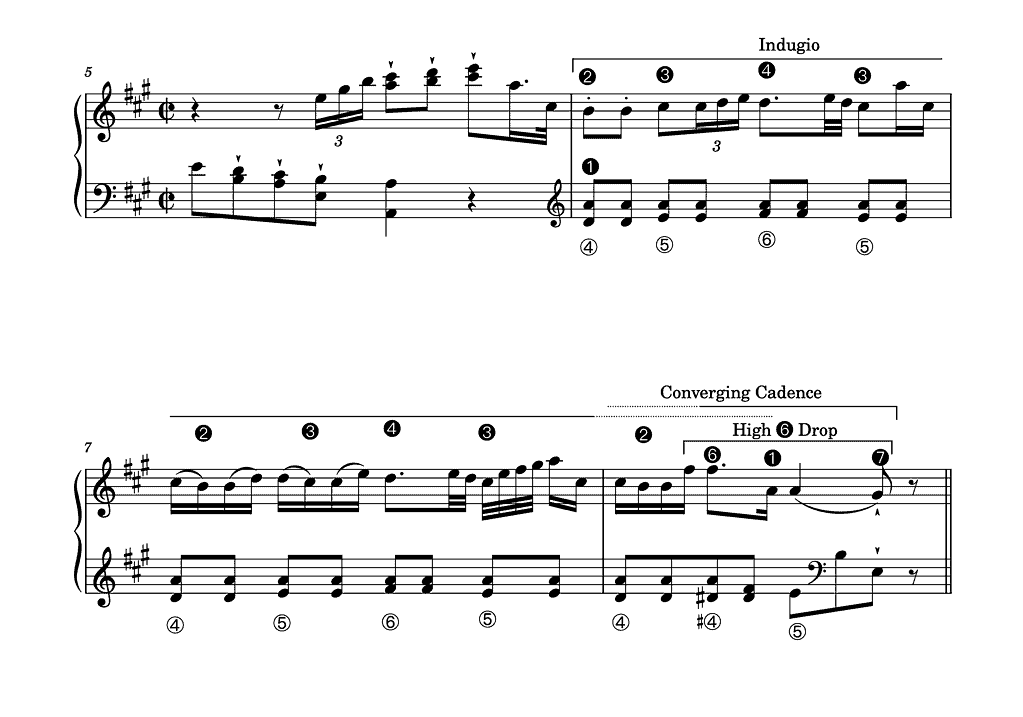

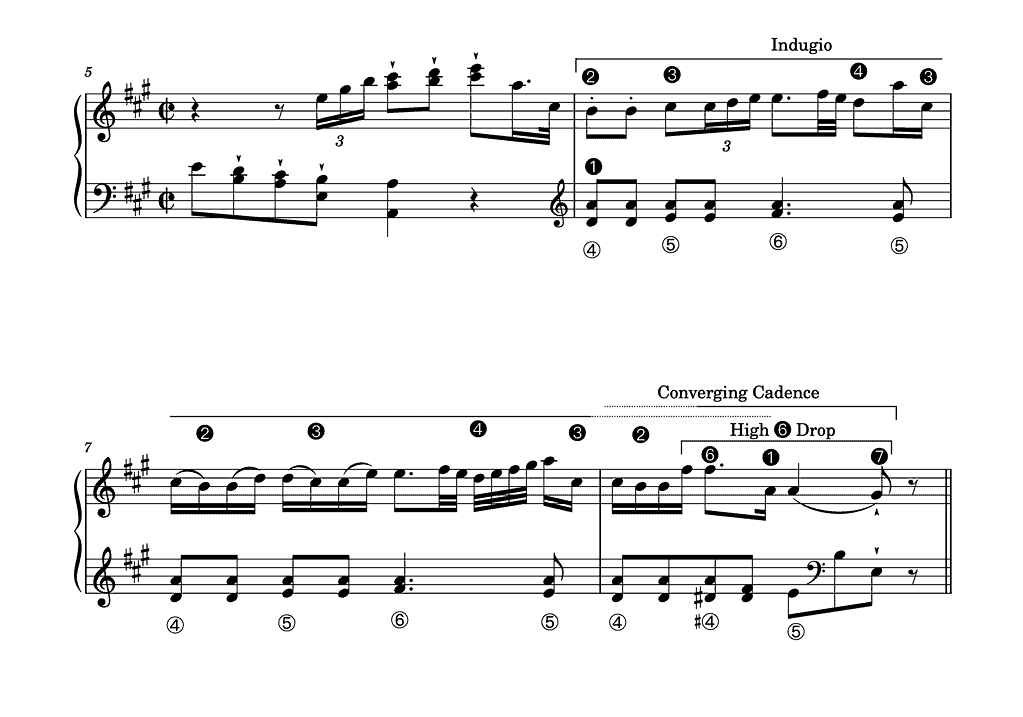

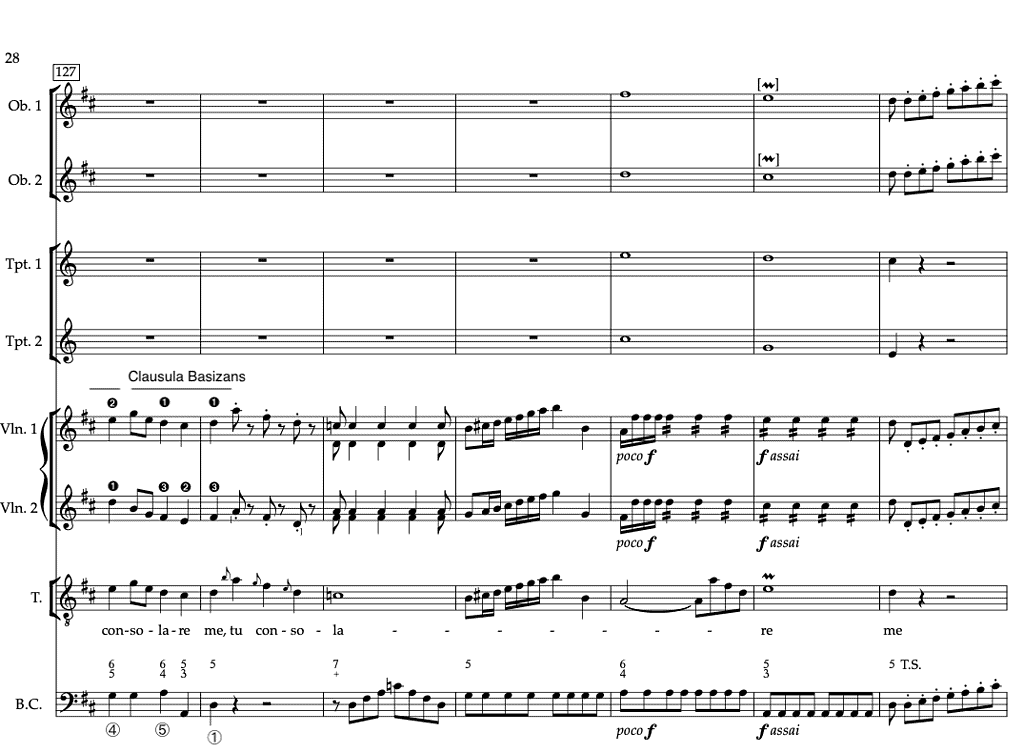

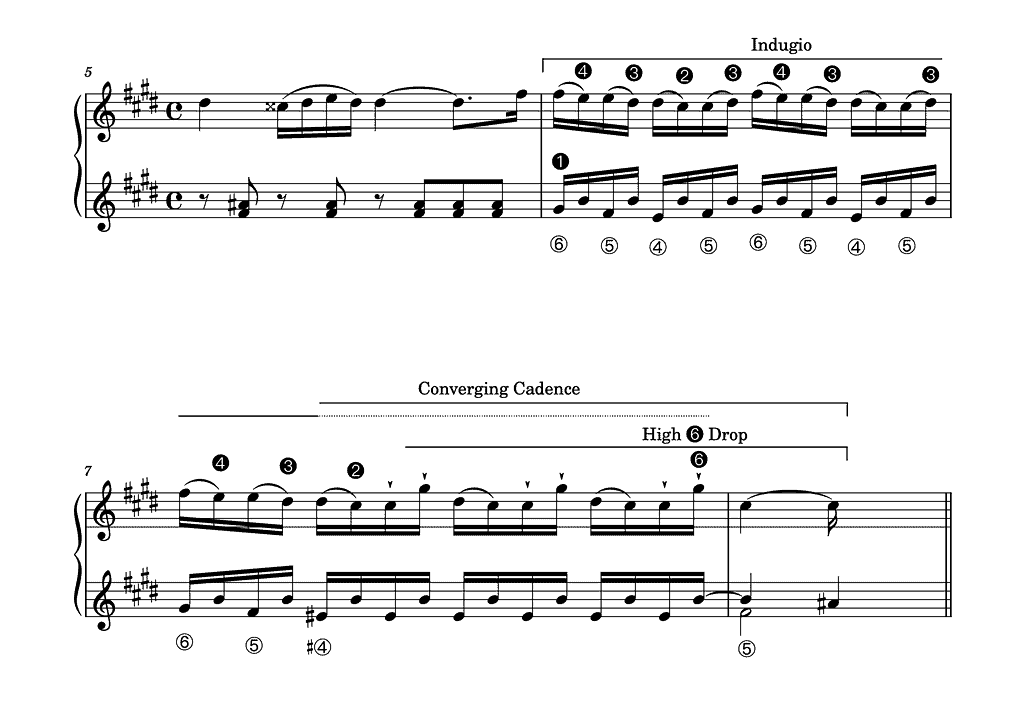

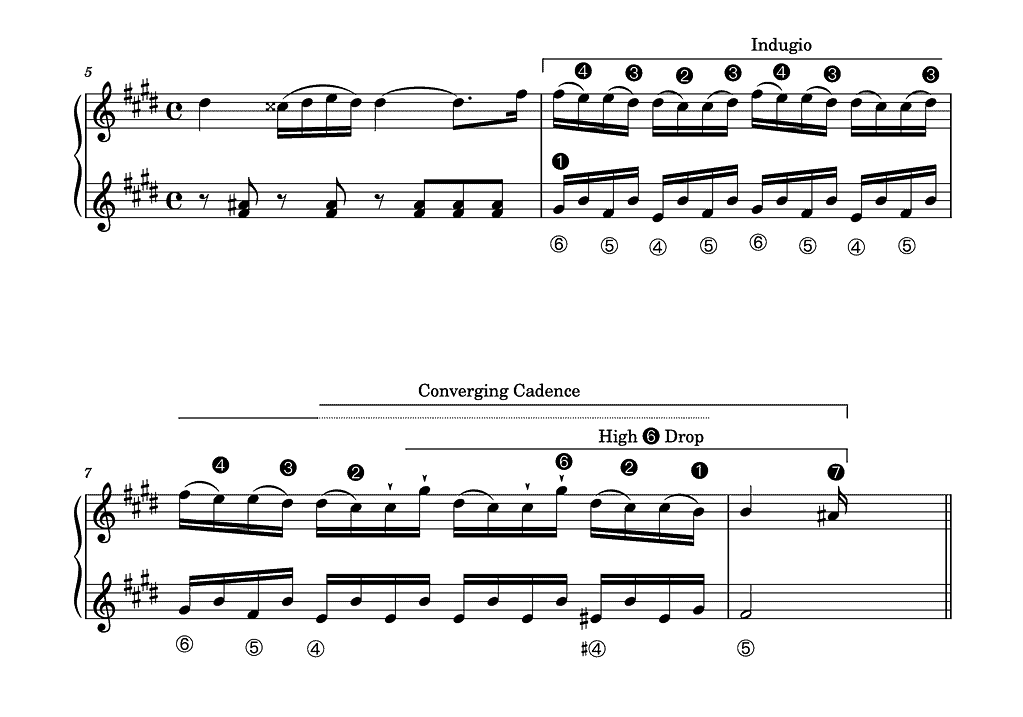

The following example shows a typical circular Indugio. Notice the typical High ➏ Drop at the very end of the circular Indugio, where it merges with a Converging Cadence with its typical ascending passus duriusculus ④–♯④ in the bass (d1–d♯1 in bar 8a).

As you can see, this example meets all the requirements of a circular Indugio. Yet although it is definitely written in eighteenth-century style and could almost pass for Haydn, this is how Haydn really wrote it:

Note that

- stages 3 and 4 (the sixth chord on ⑥ and the subsequent 6/4 chord on ⑤) don’t have the same length as in the hypothetical version (a quarter note), but that stage 3 lasts a dotted quarter note, reducing stage 4 to an eighth note

- stage 4 includes a quarter-note appoggiatura ➎ in the upper voice, delaying the expected ➍ until beat 4.

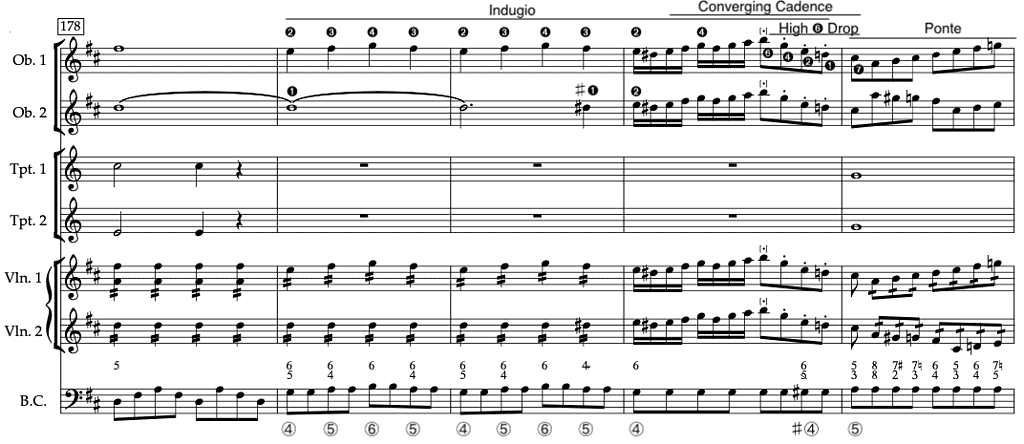

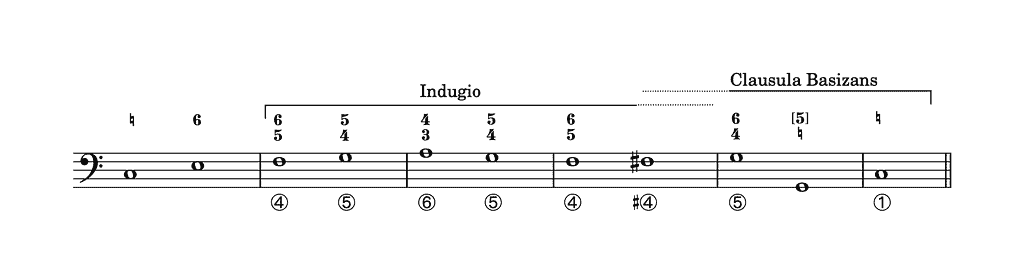

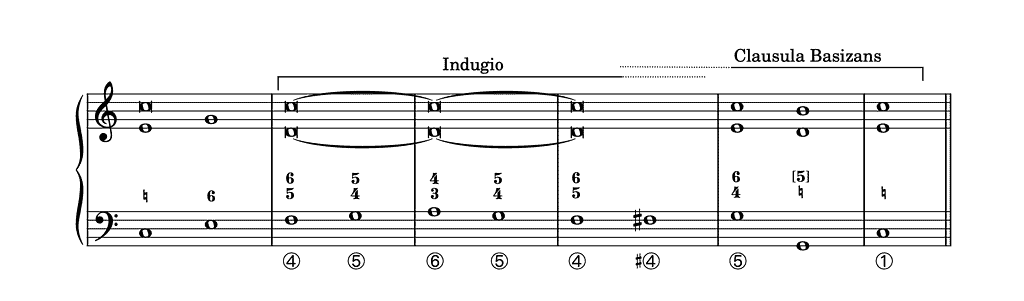

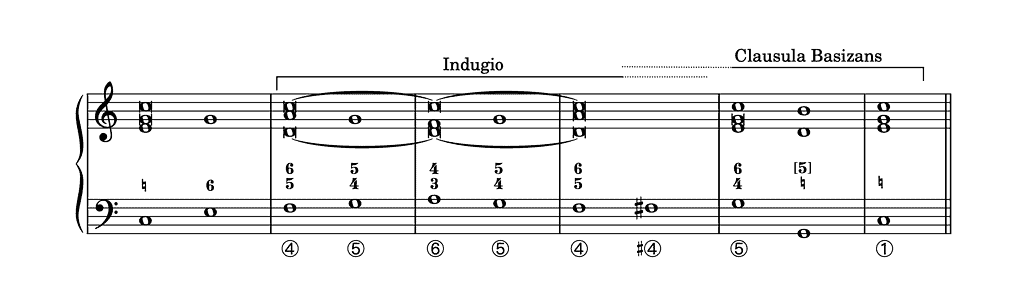

The following example shows a simpler version of the circular Indugio, without embellishments or a High ➏ Drop, which delays a clausula basizans instead of a Converging Cadence:

An example of a chromatic variant of the circular Indugio occurs in the same aria by Cimarosa:

Instead of the inner voice staying on the pedal point ➊ until the end of the Indugio, it rises chromatically to ♯➊ on beat 4 of bar 180, temporarily focussing on E minor.

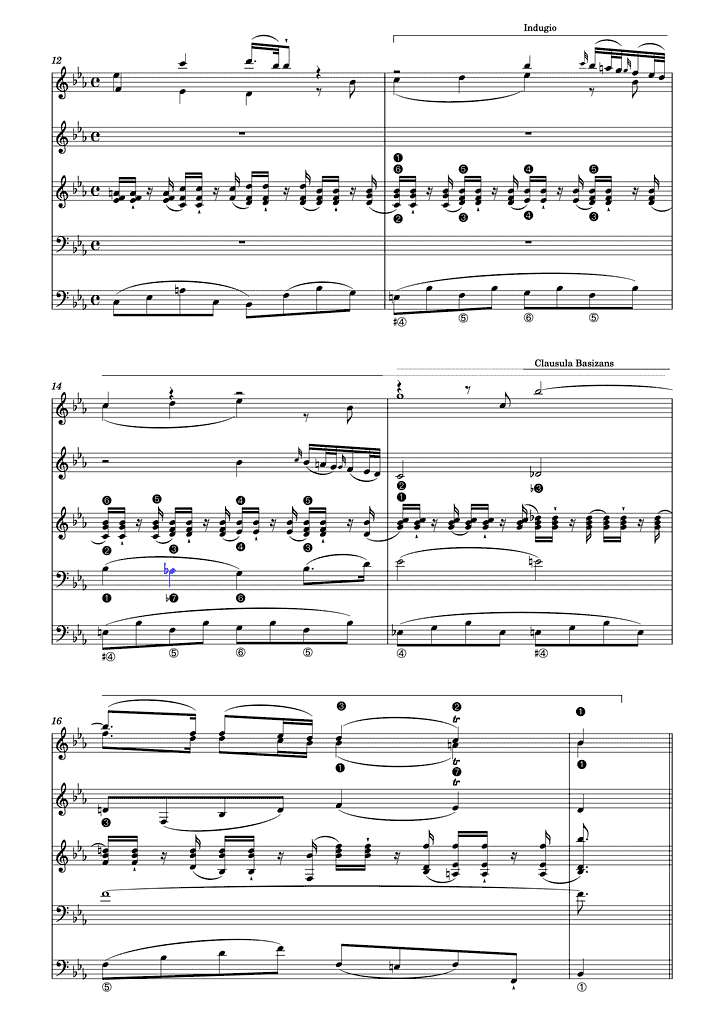

Another type of chromatic circular Indugio occurs in the Adagio of Mozart’s Gran Partita, a movement that is a rare gem:

Instead of each rotation of the circular Indugio starting on ④ in the bass —obviously a valid option, they start on ♯④. Two beats later, however, the upper part of the circular Indugio does give ➍ after the passing 6/4 chords, making the occurrences of ♯④ sound like a chromatic alteration rather than of a cue to potentially modulate. And Mozart further enhances this chromatic setting. Note

- the a♭ on beat 2 of bar 14 (in blue), which adds the minor third to the 6/4 chord thereby tonicizing the E flat major sixth chord of beat 3

- the occurrences of E♭ in bar 14a, creating a diminished seventh chord on ♯④ that leads to the clausula basizans (here a stretched cadenza composta).

Note also how the circular Indugio turns into a ‘regular’ Indugio in bar 15.

This brilliant example further teaches us that a circular Indugio doesn’t necessarily have to be written in three parts, although that is the most common setting. Indeed, it can also be in four parts, with the fourth part producing the melodic inversion of the bass (➏–➎–➍–➎–➏).

(This movement contains two more statements of this Indugio, one in C minor from 21b and a final one in E flat major from bar 37. The conclusion/continuation of the one in C minor is quite unexpected because Mozart does use ♯④ to actually modulate (to G minor) after two rotations of what appears to be an Indugio in C minor. Check this out!)

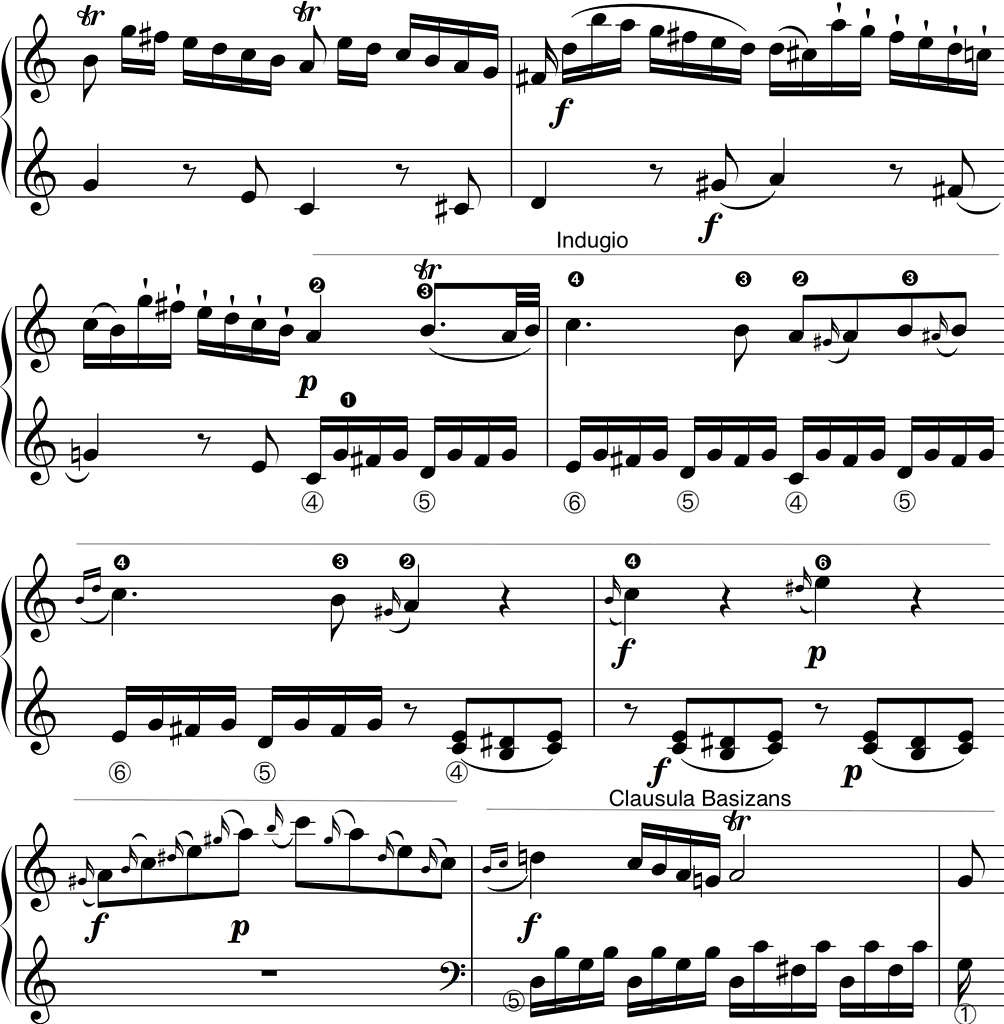

Mozart clearly liked the succession of a circular Indugio and a ‘regular’ Indugio. In the opening allegro of his first keyboard sonata, a circular Indugio and a ‘regular’ Indugio drastically delay the essential expositional closure, which together last four and a half bars:

Note also how the upper voice produces a suspension towards the end of each rotation of the circular Indugio by holding ➍ for the length of a dotted quarter note instead of just a quarter note.

(The same schema returns in the recapitulation, in the home key of C major (bars 86b–91).)

The Circular Indugio with Pedal Points on ➊ and ➋

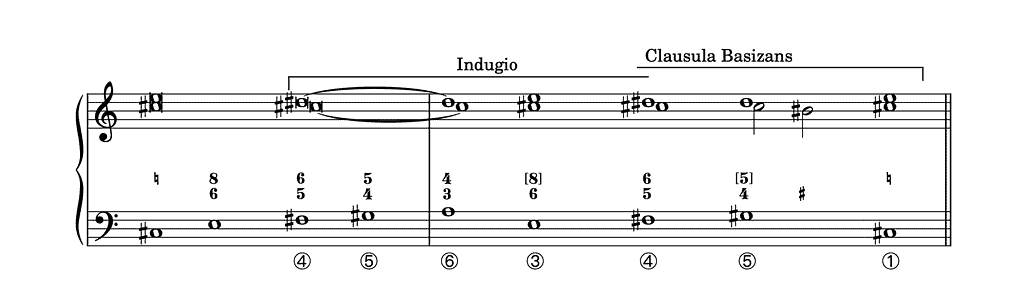

A (three-part) circular Indugio can also occur with a pedal point in each of the upper voices, one on ➊, another on ➋. In an autograph by the Neapolitan maestro Saverio Valente (before 1750–after 1813), an extensive partimento is devoted to this schema, where it is called a cadenza finta (feigned cadence). Below you can see the esempio (Italian for example, model) that introduces the partimento:

This is a possible three-part realization:

As you can see from the thoroughbass figures and my realization, the vertical sonorities of the circular Indugio with two pedal points are just the result of the encounter of the two pedal points and the bass. While ⑤ of a ‘regular’ circular Indugio is set with a weak-beat 6/4 chord, in this type of circular Indugio it is set with a weak-beat 5/4 sonority. And while ⑥ of a ‘regular’ circular Indugio is set with a strong-beat sixth chord, in this type of circular Indugio it is set with a weak-beat 4/3 sonority. In other words, neither sonority is independent own but extends the 6/5 chord; so the ⑤–⑥–⑤ snippet is purely ornamental while the upper voices remain in place.

Like a four-part circular Indugio with one pedal point (on ➊), a four-part Indugio with pedal points on ➊ and ➋ includes the melodic inversion of the bass (➏–➎–➍–➎–➏) as the fourth part. The following example is a possible realization of Valente’s esempio in a four-part setting:

(See also Sanguinetti (2012), p. 111.)

The Interrupted Circular Indugio

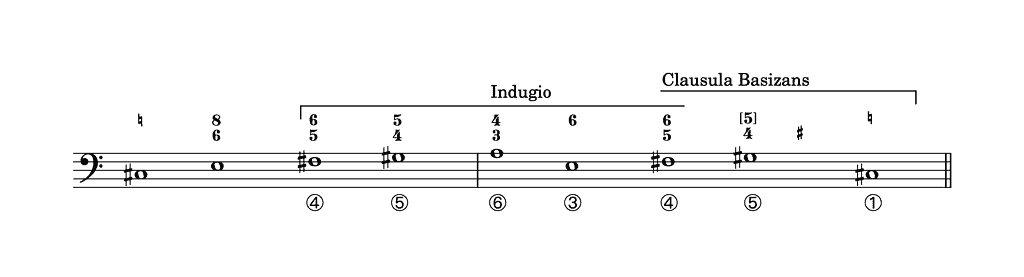

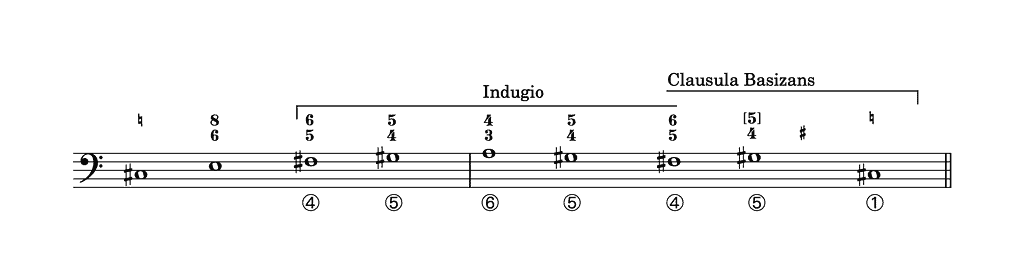

In a circular Indugio, the bass rises stepwise from ④ to ⑥, then descends again stepwise back to ④. However, descending to ④ can also be done via a leap to ③ instead of a two descending step via ⑤, in which case the circular bass movement is interrupted. Valente deals with this variant as well. He also names it a cadenza finta and again gives both its model and an extensive partimento for the student to work on. Below you can see the esempio (in C sharp minor) that introduces the partimento:

This is a possible three-part realization:

In this case, the fourth bass note of the circular Indugio is set as an independent, albeit light, sixth chord instead of being treated as a passing note. (The resolution of the 4/3 sonority, however, remains irregular. Whereas the third of this sonority usually descends stepwise to ➐, it stays put while the fourth rises stepwise.) To clarify the difference between an interrupted and an uninterrupted circular Indugio, I have transformed Valente’s esempio of an interrupted circular Indugio into an uninterrupted version by changing ③ (e, the schema’s fourth note) into ⑤ (g♯) with the appropriate thoroughbass figures:

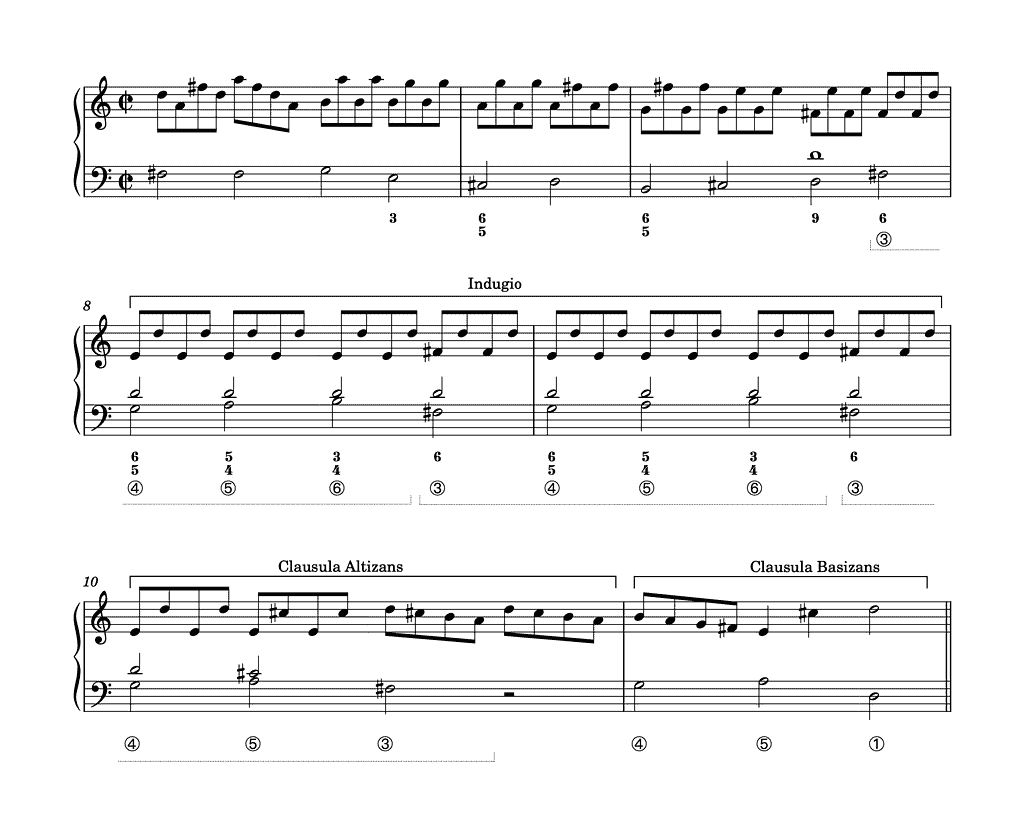

Below you can see an example of an interrupted circular Indugio from a keyboard toccata by the Neapolitan composer and maestro Leonardo Leo (1694–1744). In contrast to Valente’s esempio, however, the ④–⑤–⑥–③ snippet of this exemplar occurs twice, the second of which is not followed by one but by two cadences (successively a clausula altizans and a clausula basizans).

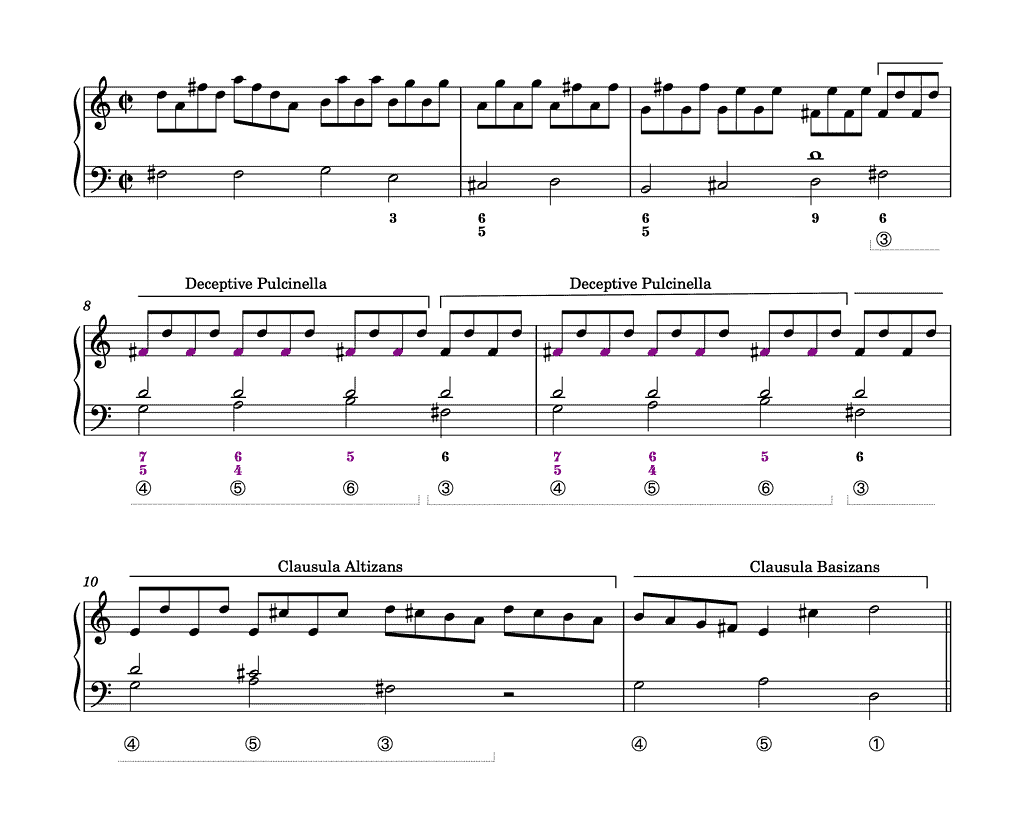

Note also the dotted brackets below the bass stave, which suggest a slightly different way of looking at this passage. They point to two failed cadential attempts that begin on ③ and end on ⑥, and the aforementioned weak clausula altizans that also begins on ③. The fact of recognizing these ③–④–⑤–⑥ snippets makes it clear that they could have been set differently, that each of them could have been set as a deceptive Pulcinella or a deceptive cadence, whose basses are identical.

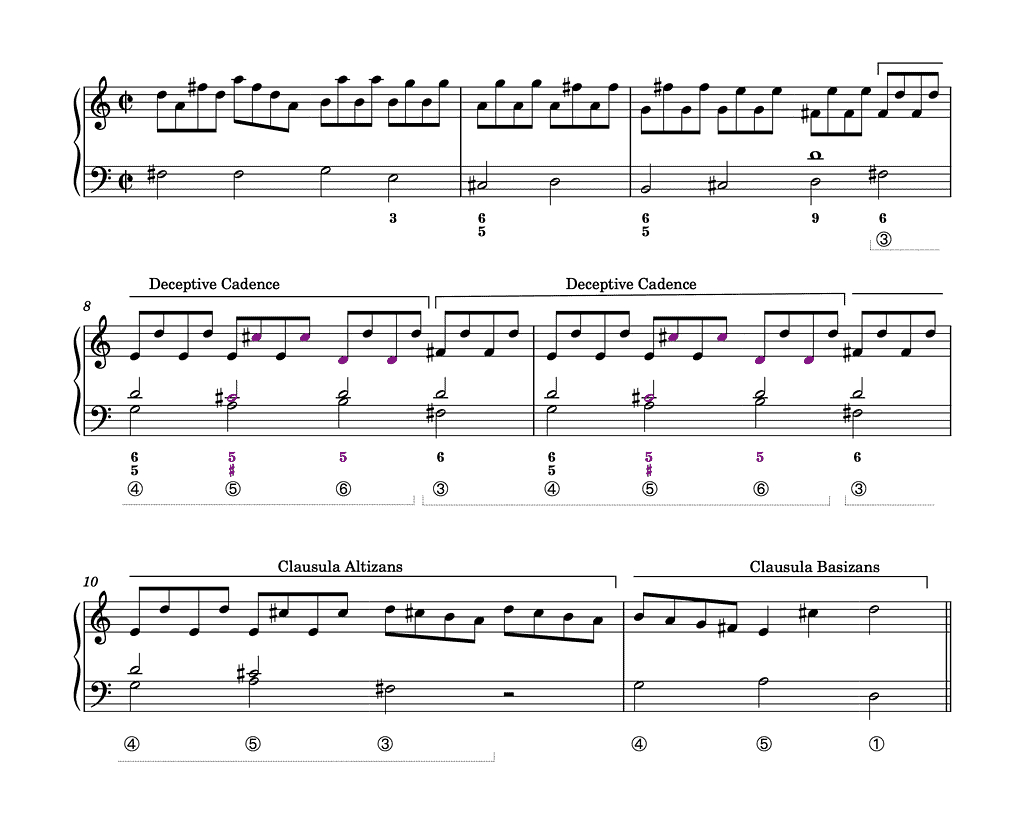

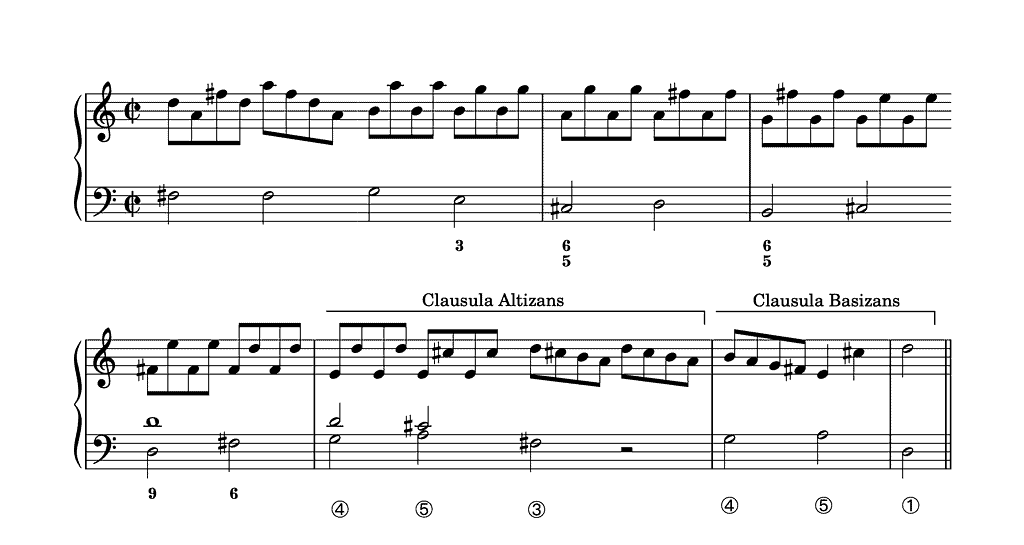

To make these different options clear, I have made two alternative versions, the first with twice a deceptive Pulcinella, the second with two deceptive cadences. (Differences in notes and thoroughbass figures are indicated in purple.)

And to illustrate the optional character of the Indugio, I have made the following hypothetical version, in which I have omitted the Indugio. In this version, bar 7 leads directly to the clausula altizans and the clausula basizans.

The Metrically Shifted Circular Indugio

A circular Indugio can also be built as follows:

- a circular rotation of a ⑥–⑤–④–⑤–⑥–… pattern in the bass, with ⑥ being metrically the strongest

- a circular rotation of a ➍–➌–➋–➌–➍–… pattern in the upper voice in parallel sixths with the bass, with ➍ being metrically the strongest

- a pedal note on ➊ in the middle voice.

This voicing leading results in:

- a sixth chord on ⑥

- a passing 6/4 chord on ⑤

- a 6/5 chord on ④.

To distinguish it from the circular Indugio, I call it the metrically shifted circular Indugio. The following example shows such an Indugio:

(The same schema returns in the recapitulation, in the home key of E major (bars 58–59).)

This passage is also somewhat special for several reasons.

First, the left hand does not first go back to e(♮)1 on beat 2 of bar 7 in the left hand, before moving to e♯1 only on that bar’s last beat. Here you can see that hypothetical solution:

The unexpected introduction of ♯④ in Haydn’s version on beat 2 of bar 7, which is extended until the end of that bar, makes these three beats stand out as an Indugio on ♯④ merged with the Converging Cadence.

Secondly, the melodic descent from the High ➏ Drop doesn’t occur in one part, but starts in the top part to end in the middle part. In the hypothetical version above, I have normalized this to make this clear.

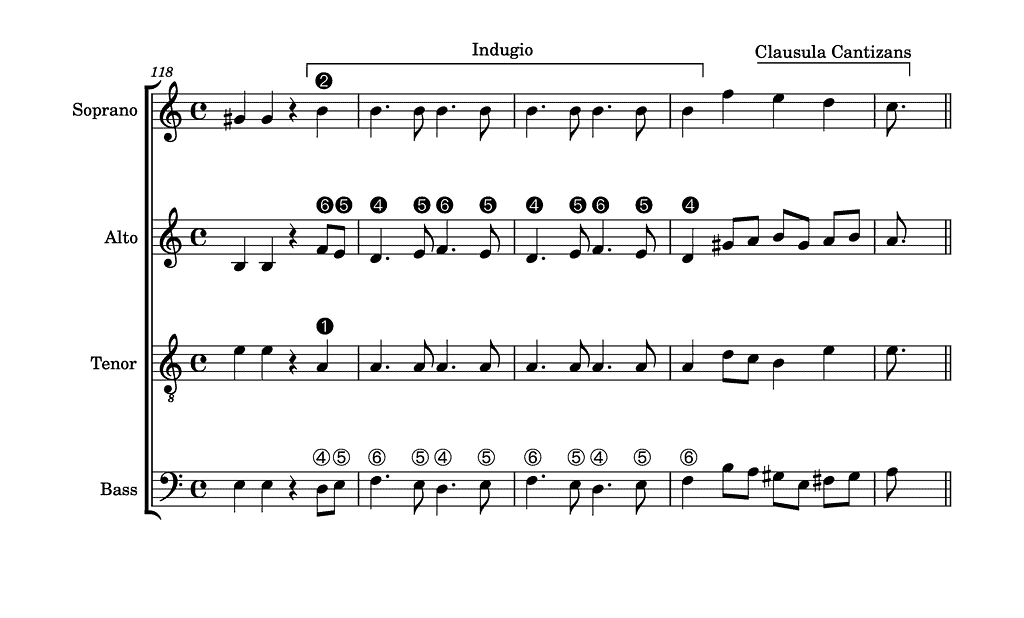

We saw above that a circular Indugio can also be set in four parts, in which case the fourth part gives the melodic inversion of the bass (➏–➎–➍–➎–➏). If one swaps the bass and that added fourth part, obviously written in invertible counterpoint, one gets a four-part metrically shifted circular Indugio. Below you can see an example of such an Indugio from a mass by Mozart:

Note that this metrically shifted circular Indugio is followed by a clausula cantizans.

Further Reading (Selection)

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).