This essay is the first of two exploring a schema that Robert O. Gjerdingen has labelled Indugio (Italian for the act of lingering).

An Indugio is essentially a pedal point on ④ set with a sixth chord or a 6/5 chord used to postpone the conclusion of a cadence.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in an upper part (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Note further that ‘Bar 1a’ refers to the first half of bar 1, ‘bar 1b’ to its second half.

Term and Interpretation

The term and interpretation of the Indugio come from Robert O. Gjerdingen. He defines this schema as a pedal point on ④ set with a sixth chord or a 6/5 chord that occurs in several variants. An Indugio has the specific task of increasing the expectancy of cadential closure, by staying on ④ longer than expected.

The Indugio Set with a 6(/5) Chord

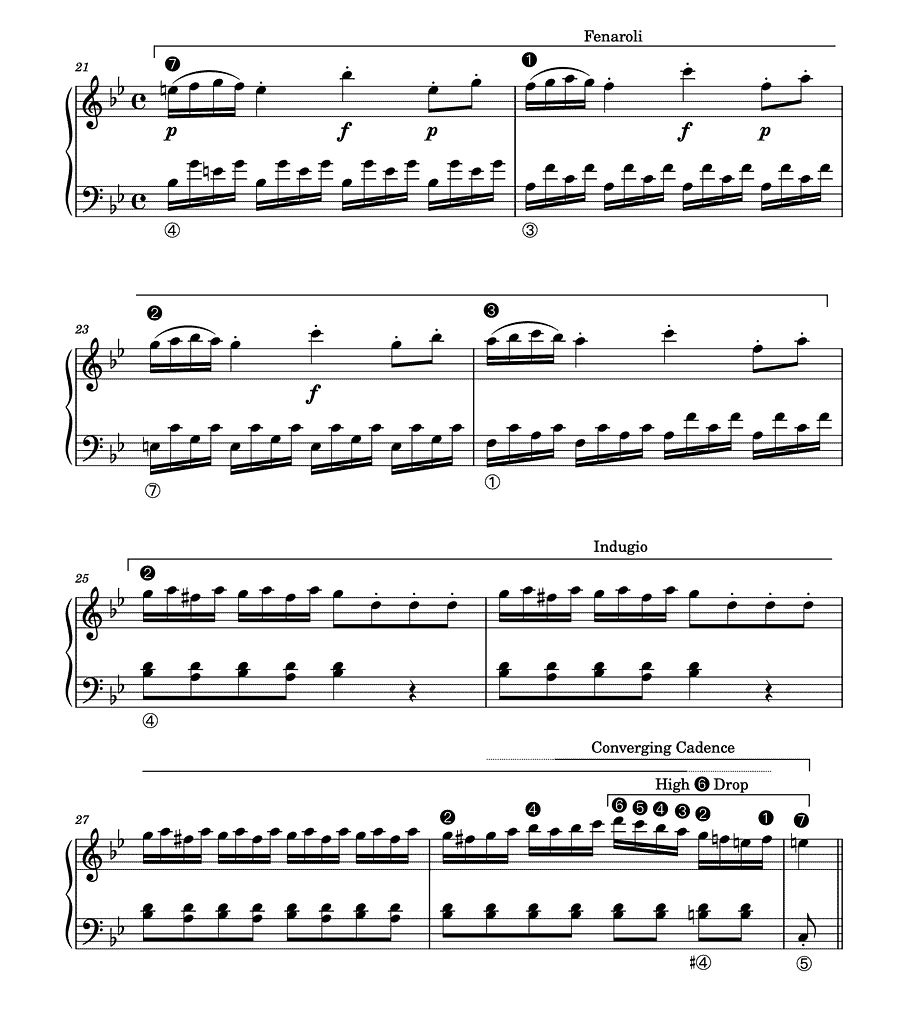

In his book Music in the Galant Style, Gjerdingen gives as what he sees as a typical setting of an Indugio the following excerpt —in the local key of F major— from the Keyboard Sonata in B flat major C 78 by Domenico Cimarosa:

(Brioso means lively, joyful)

According to Gjerdingen, this example of an Indugio has many features of the schema:

- a pedal point in the bass on ④ (here b♭) embellished with lower neighbour notes ③ (here a)

- a pedal point in the treble on ➋ embellished with lower neighbour notes ♯➊ (here f♯2)

- a ➋–➍–➏ ascent towards the end of the Indugio (bar 28)

- a temporary focus on the minor key of ② (here G minor) due to the neighbour-note motives with ♯➊ (here f♯2) in the treble

While not mentioned by Gjerdingen, I would also like to point out the typical High ➏ Drop at the very end of the Indugio, where it merges with a Converging Cadence with its typical ascending passus duriusculus ④–♯④ in the bass (b♭–b(♮) in bar 28). As Gjerdingen argues, the fact that an Indugio concludes with a Converging Cadence is indeed typical galant behaviour (Gjerdingen (2007), p. 278).

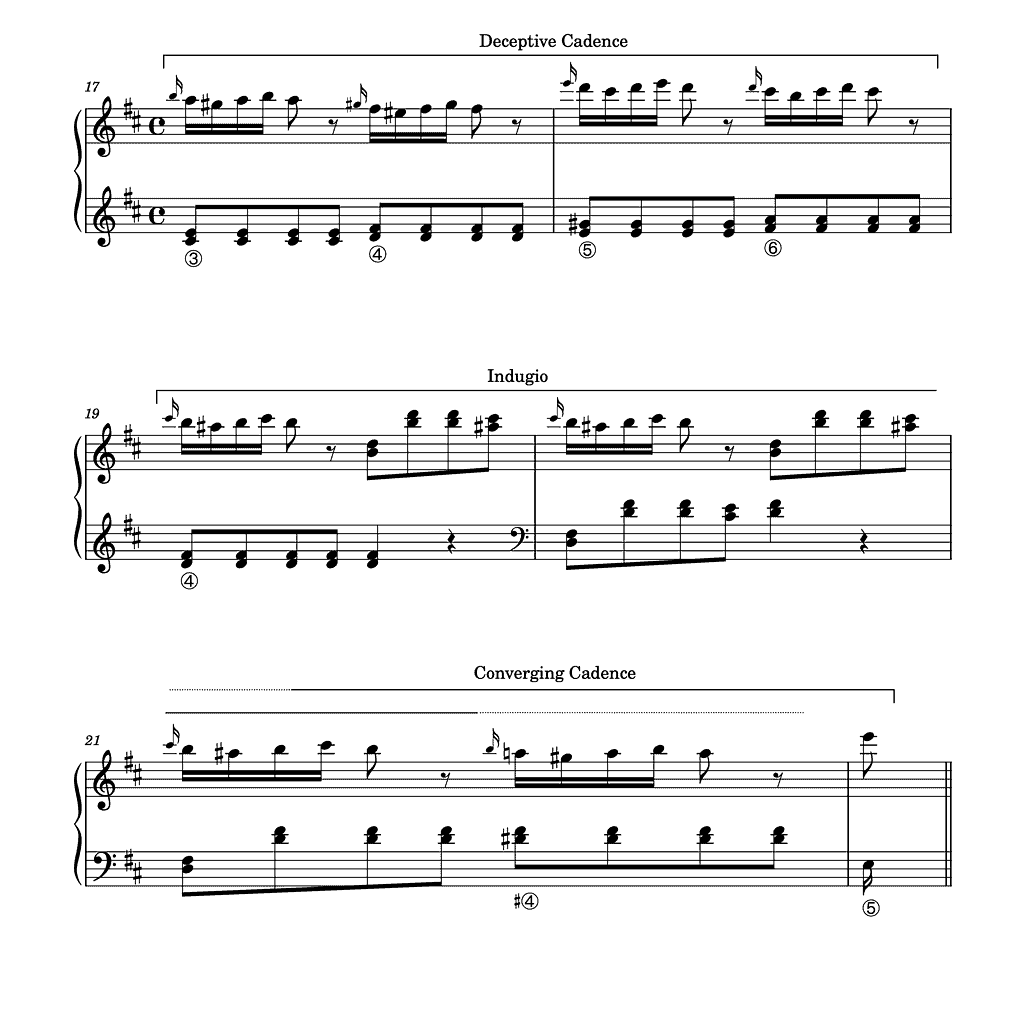

In the following example, a deceptive cadence (bars 17–18) is followed by an Indugio, in which ④ is extended over two and half bars, that again leads to a Converging Cadence:

Notice that lower neighbour notes occur regularly only in the treble (a♯2), still temporarily zooming in on B minor. (The bass has only one lower neighbour note, in bar 20a.)

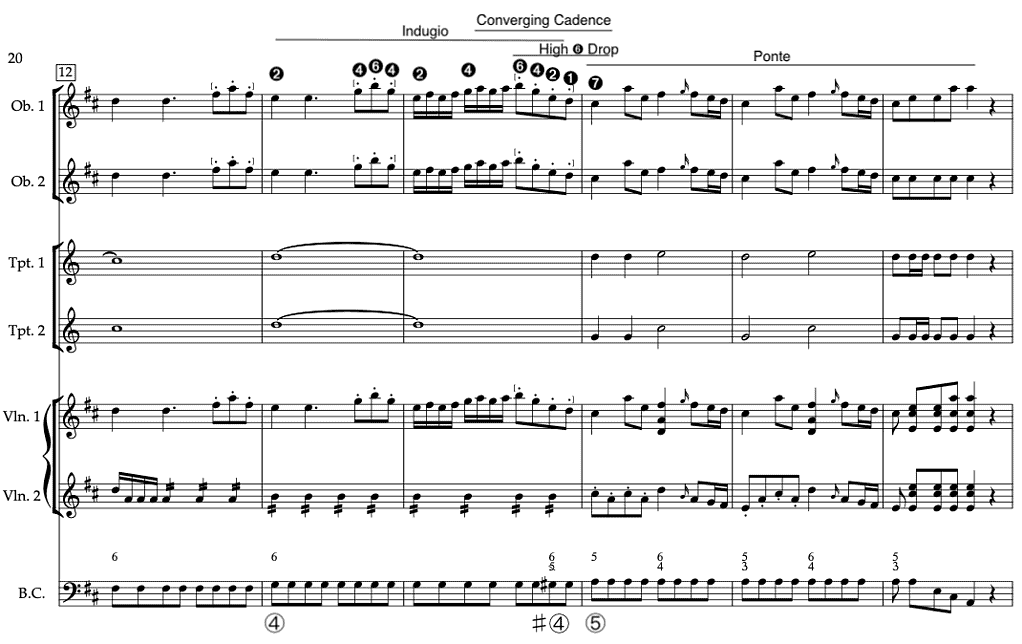

In the next example, again by Cimarosa, neighbour notes are absent in both pedal points of the Indugio. However, the ➋–➍–➏ ascent is prominent, appearing not once but twice. Again, this Indugio leads to a Converging Cadence, which is extended here by a pedal point on ⑤, a gesture that schemata theorists would probably label as a Ponte. Note also the High ➏ Drop at the very end of the Indugio and the beginning of the Converging Cadence including the ascending passus duriusculus ④–♯④ in the bass (g–g♯ in bar 14).

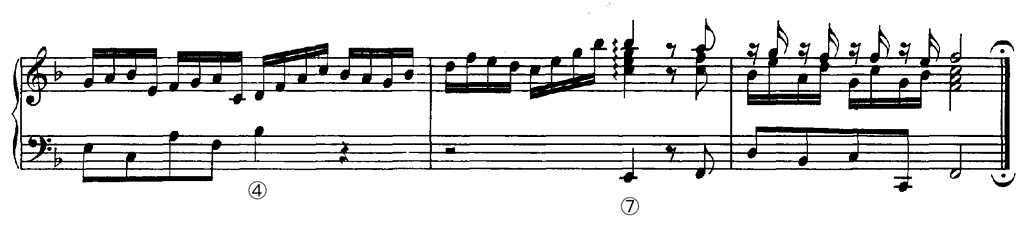

A more rudimentary version of an Indugio occurs at the end of the (Little) Keyboard Prelude in F major BWV927, where the 6/5 chord on ⑦ is delayed by several beats due to a pedal point on ④:

(Whether or not this composition is by Bach’s hand is not the issue here. That it belonged to the Bach circle is a fact: it appears in the Klavier-Büchlein vor Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, a keyboard book his father began compiling on 22 January 1720, two months after Friedemann’s ninth birthday.)

Note how

- the sixth chord on beat 4 of bar 13 is ornamented on beat 3 by an appoggiatura 9/7 chord (on ④)

- the fifth (f2) is added to the sixth chord on beat 1 of bar 14, becoming a 6/5 chord

- the 6/5 chord on ⑦ that occurs on beat 3 of bar 14 is anticipated in the right hand on beat 2 of bar 14.

The Indugio Starting with a Triad

Instead of starting with a sixth chord or a 6/5 chord, an Indugio can also start with a triad. If it is approached from ① or ③, ♭➐ can be included in the chord of one of those scale steps, causing this snippet to briefly focus on the key of ④. That happens in this example:

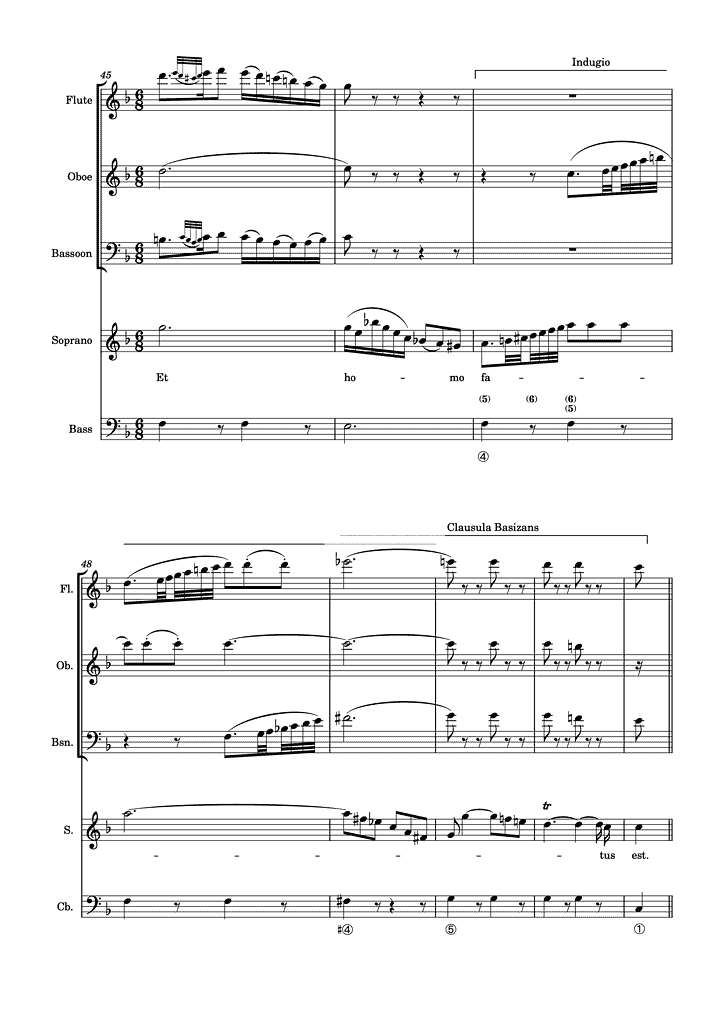

This excerpt, in the local key of C major, begins with a clausula altizans (bar 45–46). The final chord of this cadence, a sixth chord on ③, is then expanded by a diminished fifth, B♭, temporarily focussing on F major instead of C major. This implies that the downbeat of bar 47, the start of the Indugio, is heard as an F major triad. This triad is immediately transformed into a sixth chord —a D minor sonority— due to the first two embellishing notes in the soprano —the two thirty-seconds b♮1 and c♯2— and the d2 on the third eighth note. In the middle of the bar, the oboe begins its scale on c(♮)2, transforming the sixth chord into a 6/5 chord. To make all this clear, I have added thoroughbass figures in parentheses. This Indugio beautifully heightens the expectation of the clausula basizans that concludes this C major section.

Note also the final eighth note g♯1 in the soprano in bar 46, a typical galant chromatic embellishment in an upper part when the bass goes from ① or ③ to ④ in a major key. (In his groundbreaking book Music in European Capitals — The Galant Style, 1720–1780 from 2003, Daniel Heartz refers to this type of embellishment multiple times.)

The Indugio Set with a Neapolitan Sixth Chord

As we saw above, the pedal point on ④ of an Indugio can be set with a triad, a sixth chord or with a 6/5 chord. Another option is to set ④ with a Neapolitan sixth chord (including ♭➋ instead of ➋), an option that is typical for a minor key, although it can also occur in major.

Towards the end of the third and final movement of his Keyboard Sonata in C minor Hob. XVI: 20, Haydn writes the following passage:

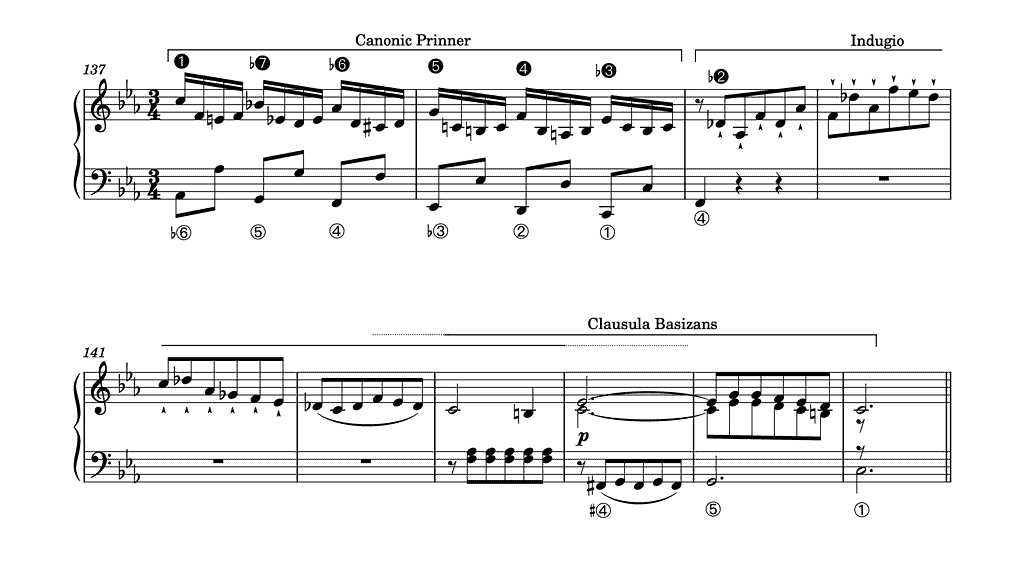

In this case, a canonic Prinner is followed by an Indugio based on the Neapolitan sixth chord in C minor (with D♭). And notice

- that, while the bass does go from ④ to ♯④, the subsequent cadence is not a Converging Cadence but a clausula basizans

- how Haydn zooms in on the key of D flat major in bar 141 by inserting g♭1 as a passing note.

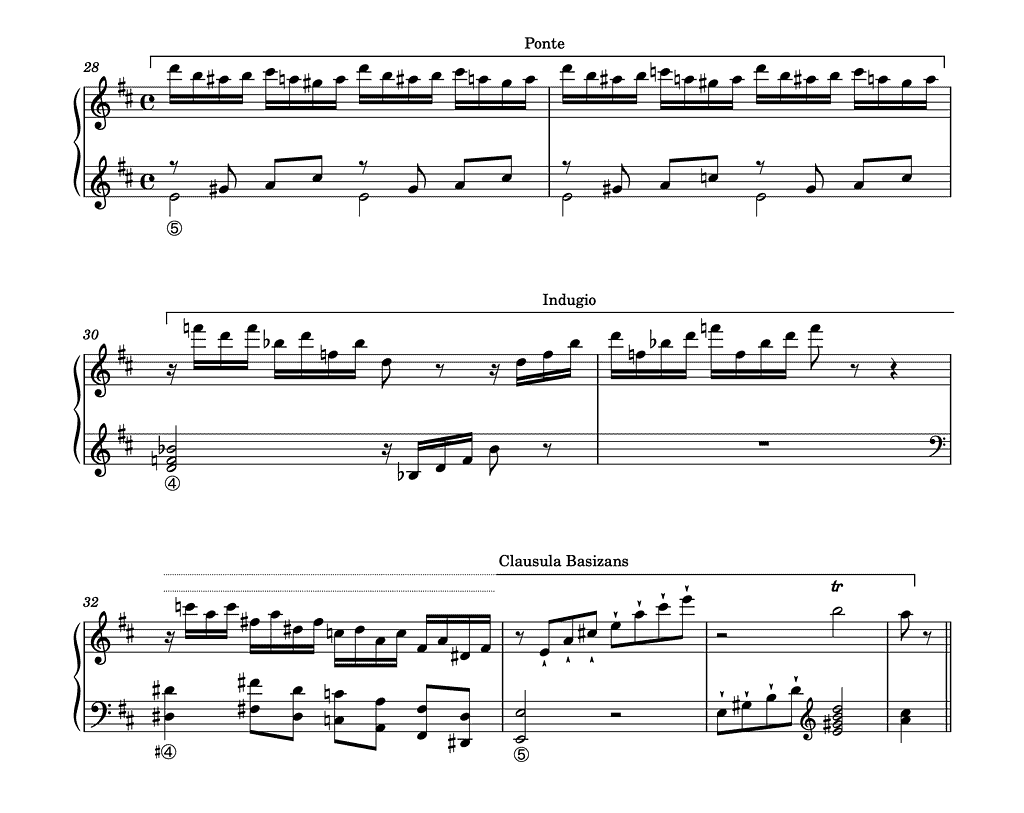

I mentioned above that a Neapolitan sixth chord can also occur in major. While this is indeed true, it is usually introduced when the major key has temporarily switched into a minor key. Consider the example below.

This excerpt begins with a pedal point on ⑤ in A major, a gesture that schemata theorists would probably label as a Ponte. It is followed by an extended Neapolitan sixth chord (with B♭) that acts as an Indugio, building up tension towards the structurally concluding clausula basizans of this movement’s exposition.

Note again that ♯④ occurs between ④ and ⑤ (bar 32).

Further Reading (Selection)

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Heartz, Daniel. Music in European Capitals — The Galant Style, 1720–1780 (New York: Norton & Company Ltd., 2003).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).