The Monte is a schema widely used in the 17th and 18th centuries and exists in many variants, some of which are discussed in this essay. For the schema’s characteristics see my essay The Monte: The Basics.

I will explore five variants of the Monte in this essay: the minor-key Monte ending in v, the major-key Monte ending in v, the (♭VI–)♭vii–i Monte, the IV–I Monte and the borrowed Monte.

I use upper-case Roman numerals in this essay for local major keys and lower-case Roman numerals for local minor keys.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the melody (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

The Minor-Key Monte Ending in v

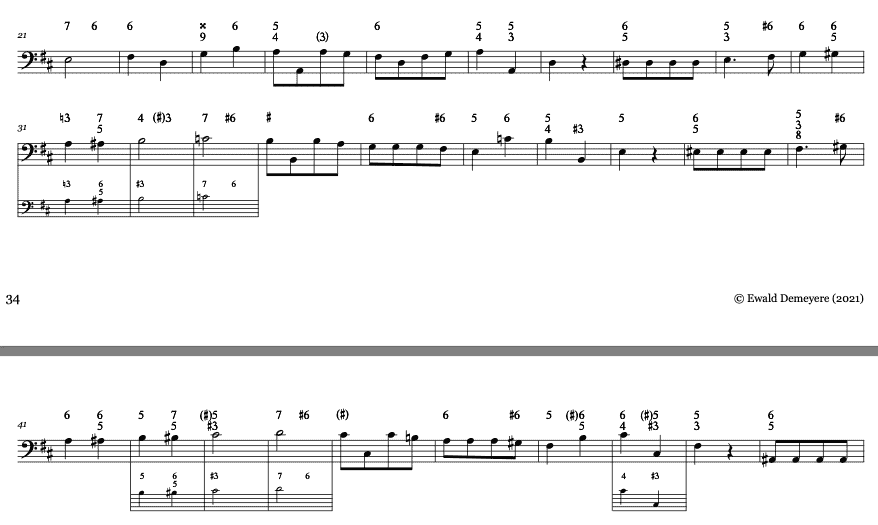

In my essay The Monte: The Basics, I explain that the second segment of a minor-key Monte is ambiguous in terms of key. While it appears to begin in v, the ending usually functions as a half cadence in the main key, i.e. ending with a major triad on ⑤ in that key. Yet the second segment of a Monte can also be written entirely in v—an unexpected hearing experience, although, as David Jayasuriya explains in his doctoral dissertation from 2016, the number of this type of Monte is modest (Jayasuriya (2016), p. 180). Consider the next example, an excerpt from partimento 6 in B minor by Fedele Fenaroli (1730–1818).

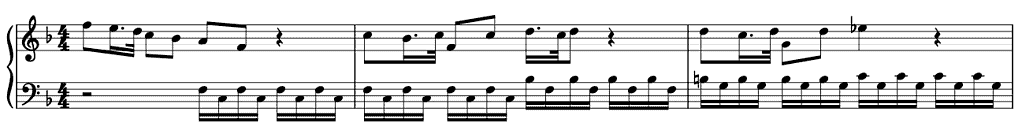

(Minor-Key Monte Ending in v: bars 28–49)

In relation to the main key of B minor, a large Monte occurs in bars 28–49. Bars 28–38 present a phrase in E minor (iv) that is transposed one step up in bars 39–49. Unlike the example by C.P.E. Bach discussed in my essay The Monte: The Basics, however, the second segment of this Monte (bars 39–49) is unambiguously written in F sharp minor (v). (To get to B minor immediately after this Monte, Fenaroli writes an extra bar with four repeated eighth notes A♯.)

Note that there is ambiguity about how to hear bar 28 and the E minor segment beginning there. After all, the phrase preceding the Monte is written in D major. This implies that an eighteenth-century musician might also have heard bar 28 as the potential start of a borrowed Fonte (for more information on that type of Fonte see my essay The Fonte in Other Keys). Only on hearing bar 39, where the bass doesn’t produce C♯ —that would have implied the start of the second segment in D major of the Fonte— but E♯, does the listener understand that this gesture is a Monte.

Below, you can see and listen to a similar Monte from the second movement (in B minor) from Haydn’s Symphony in B major Hob. I: 46. (The comparison with Fenaroli’s example is easy since the key of both pieces, and therefore of both segments of the Monte, is the same.)

(Minor-Key Monte Ending in v: bars 27/28–31), ed. T. Lanfear, public domain, available on https://imslp.org

(Both examples are also discussed in Jayasuriya’s doctoral dissertation (Jayasuriya (2016), p. 31 and 180–181).)

The Major-Key Monte Ending in v

Although not regular, the second segment of a minor-key Monte ending in v does belong to the usual modulations of a piece in minor. Highly unusual, however, is when this occurs in a piece in the major mode.

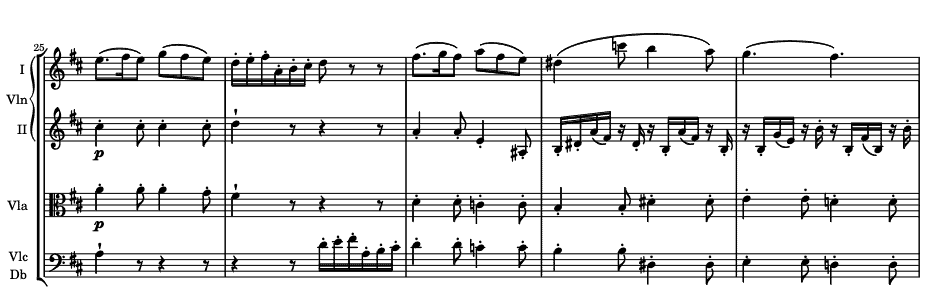

On 3 January 1722, the comic opera Li zite ‘n galera (The lovers on the galley) by Leonardo Vinci (ca. 1696–1730) had its premiere in the Teatro de’ Fiorentini, an opera house in Naples that focussed on commedia per musica. (Vinci was a successful Italian opera composer who studied at the Neapolitan Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo.) Li zite ‘n galera, sung in Neapolitan dialect, is Vinci’s first comic opera to have survived as a complete score. The B section of the first aria of this opera’s first act opens as follows:

(top voice: violins 1 & 2 in unison, lowest voice: bass group, soprano and alto parts are omitted)

After a strong clausula basizans in unison (or ⑤—① cadence) in F major (not shown), the B section opens in bar 21 with a Monte whose second segment isn’t written in C major but in C minor.

Note, moreover, that the key of the first segment is somewhat ambiguous. It could be heard in B flat major but also in F major since there is no E♭ in bar 22. Once one hears the b(♮) in the bass on the downbeat of bar 23, one might retrospectively hear the first segment more clearly in B flat major.

As far as I know, this specific type of Monte has not yet been identified.

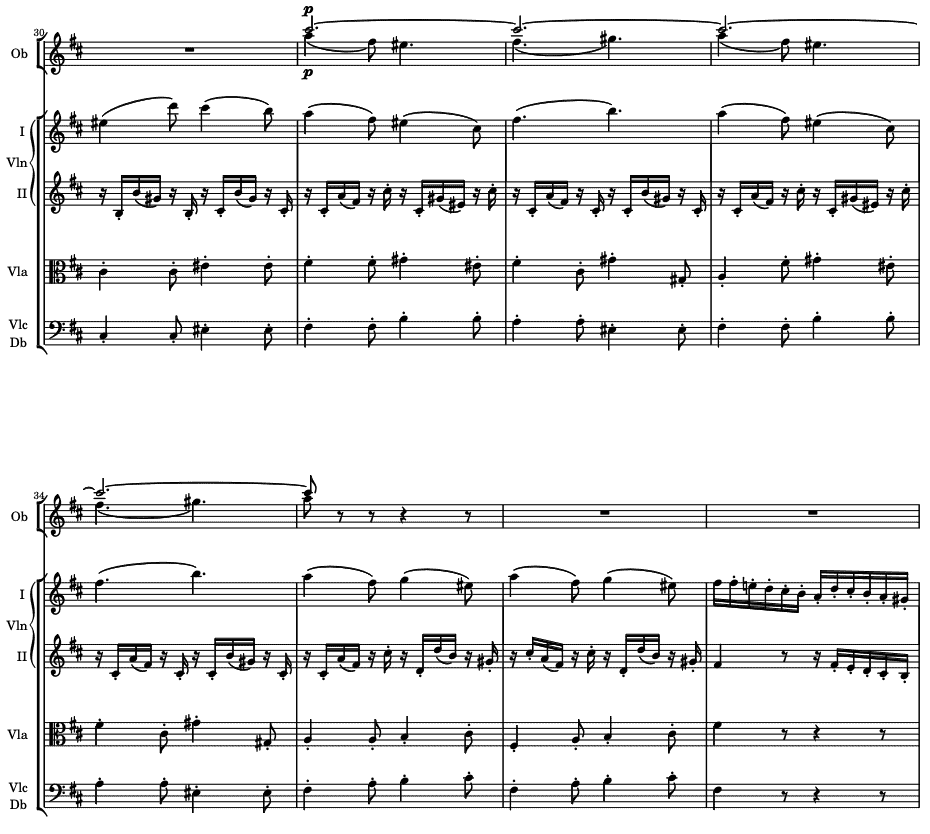

The (♭VI–)♭vii–i Monte

Another rare type of Monte occurs in partimento 32 in C major from the last book of partimenti that Fenaroli composed. (Editor Emmanuele Imbimbo calls that book the sixth one, while Fenaroli himself speaks of his fifth book, as do I. For more information on Imbimbo’s (problematic) edition of Fenaroli’s complete pedagogical output see my article On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update (2018) and the preface to my critical edition of Fenaroli’s first three books.)

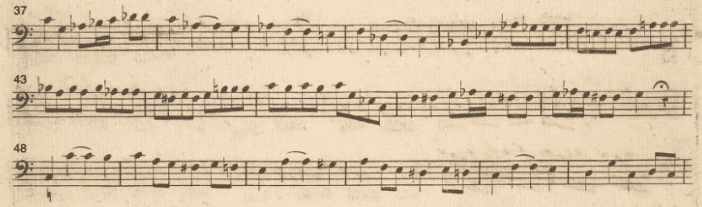

A gesture closes in bar 41 with a clausula basizans (⑤–① cadence) in A flat major. This cadence is then transposed, expanded and varied by turning it in a clausula cantizans (⑦–① cadence) first in B flat minor (bars 42–43), then in C minor (bars 44–45), each of which are anticipated with ♭⑥ (g♭ in B flat minor (bar 41b) and a♭ in C minor (bar 43b)).

For those using Gjerdingen’s edition of this partimento (https://partimenti.org/partimenti/collections/fenaroli/index.html), note the editorial error in bar 41, which I have indicated by a red line:

While the last three (eighth) notes should be g♭ (compare also bar 41b with bar 43b), the flat before the antepenultimate eighth note is lacking. This, of course, has an important consequence. While g(♮) implies that this segment is in B flat major (the major second ⑥–⑤ only occurred in a major key in 18th-century Naples), the g♭ strongly suggests that the key is B flat minor. (Still, one could still interpret g♭ as a hermaphrodite note in B flat major.)

(This example is also discussed in Jayasuriya’s doctoral dissertation (Jayasuriya (2016), p. 32–33). The author, however, seems to have based himself on Gjerdingen’s edition, including the error in bar 41, and argues that the first segment of the Monte can be seen in both B flat minor and B flat major.)

The IV–I Monte

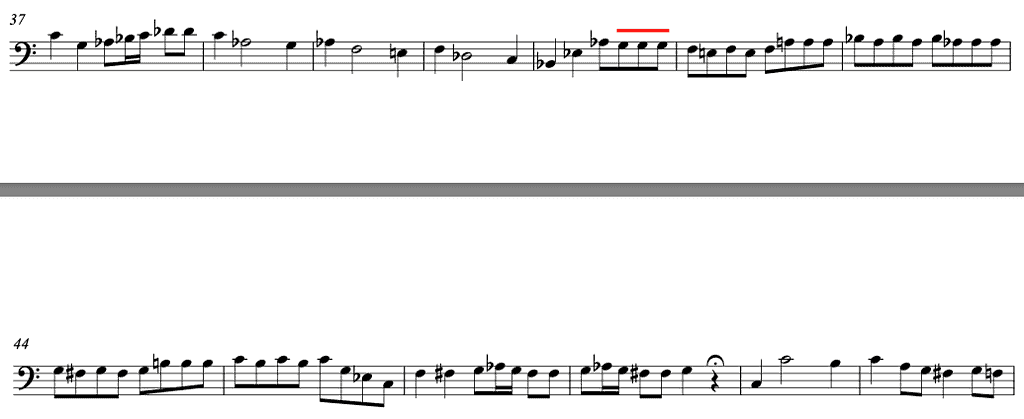

While Riepel does accept the paradigmatic Monte “when it is well used” (Riepel, Anfangsgründe vol. 3, p. 82), he prefers a Monte with sufficient variation in the second fragment and discusses in detail how this can be done. (Since a complete overview of Riepel’s recommendations would fall beyond the scope of this essay, I limit myself to one noteworthy example.) In addition to the obvious technique of varying the decoratio of the second segment, Riepel explains that it is also possible to modify the local key of the second segment. One example of what he calls a Monte within a piece in C major starts in the local key of F major (IV; bars 1–2 in the example below), while the second fragment is not set in G major (V) but in C major (I; bars 3–4 in the example below).

The Borrowed Monte

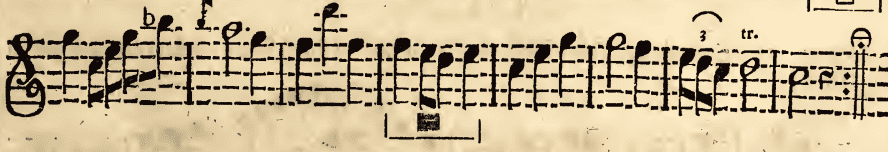

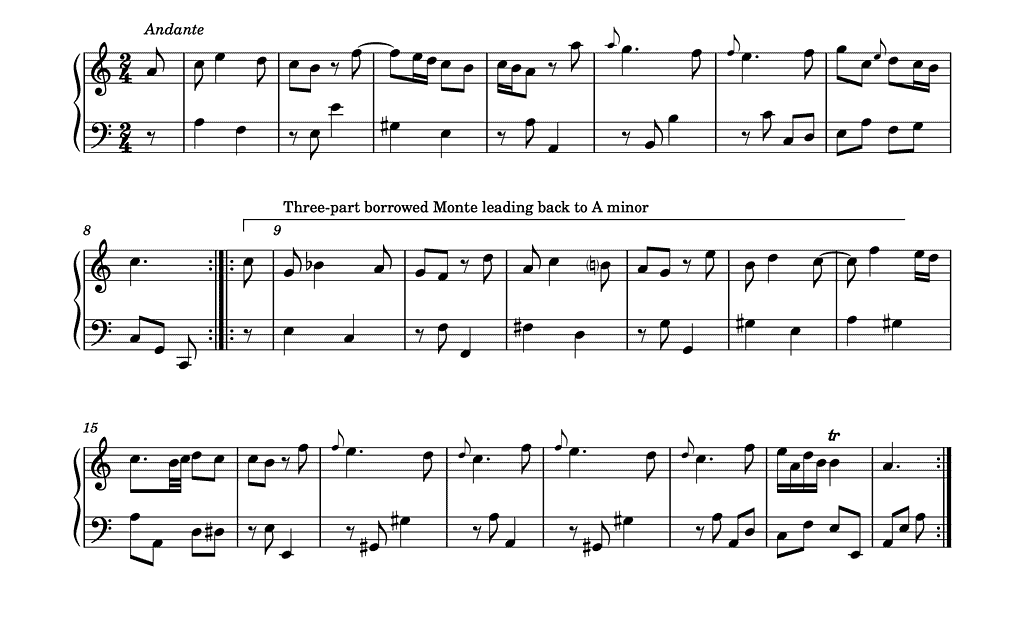

Like a Fonte, a Monte could also be borrowed. (For more information on the borrowed Fonte see my essay The Fonte in Other Keys.) This means that, in minor, the Monte doesn’t relate to the main key but to the relative major. Contrary to the Fonte, however, this is not a necessity if a composer wants to use a Monte in minor. After all, as seen above, a Monte does occur in minor, unlike a Fonte. Below you can see an example of such a Monte from Riepel’s treatise (Riepel, 1755: 123), occurring after the double barline:

Note how this borrowed Monte consists of three segments, the third of which takes us back to A minor. (Riepel gives the same version of the Monte also in the context of C major; see the section The Major-Key IV–V–vi Monte in my essay The Monte: The Basics.)

Further Reading (Selection)

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207-229.

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE, Preface and Editorial Principles, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. Partimenti Ossia Basso Numerato, Opera Completa Di Fedele Fenaroli. Per uso Degli alunni del Regal Conservatorio di Napoli (Paris: Emmanuele Imbimbo and Nicolas-Raphaël Carli, 1813).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. The Parma Manuscript — Partimento Realizations of Fedele Fenaroli (1809), ed. Ewald Demeyere (Visby: Wessmans Musikförlag,2021).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Jayasuriya, David. Fonte and Monte in the Symphonies of Joseph Haydn, PhD Dissertation (University of Southampton, 2016).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — I. De Rhythmopoeïa, oder von der Tactordnung (1752).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — II. Grundregeln zur Tonordnung (1755).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — III. Gründliche Erklärung der Tonordnung (1757).

Riepel, Joseph. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst — IV. Erläuterung der betrüglichen Tonordnung (1765).