This essay deals with the first verset (i.e. short partimento) in C minor by Stanislao Mattei (1750–1825), which is the 61st verset in the collection and is numbered as such in the Wessmans edition.

The versets by Mattei are a remarkable collection of pedagogical pieces intended to be realized in three parts at the keyboard with great concern for contrapuntal quality. Moreover, instead of focusing on just one realization, students had to explore as many options as possible.

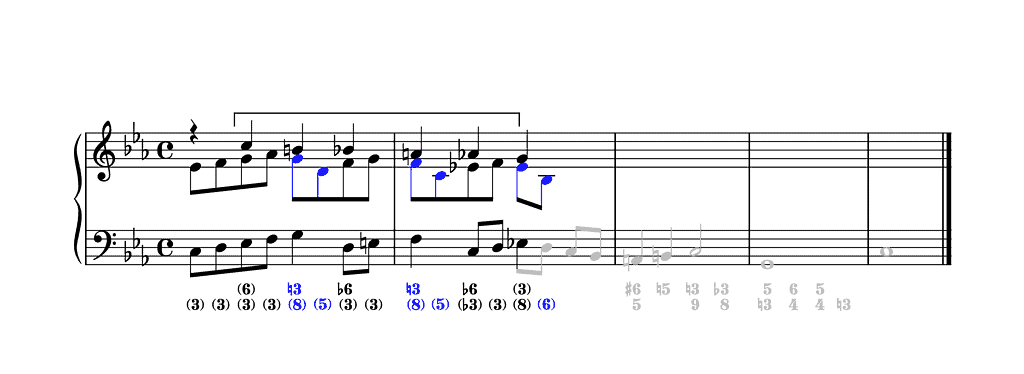

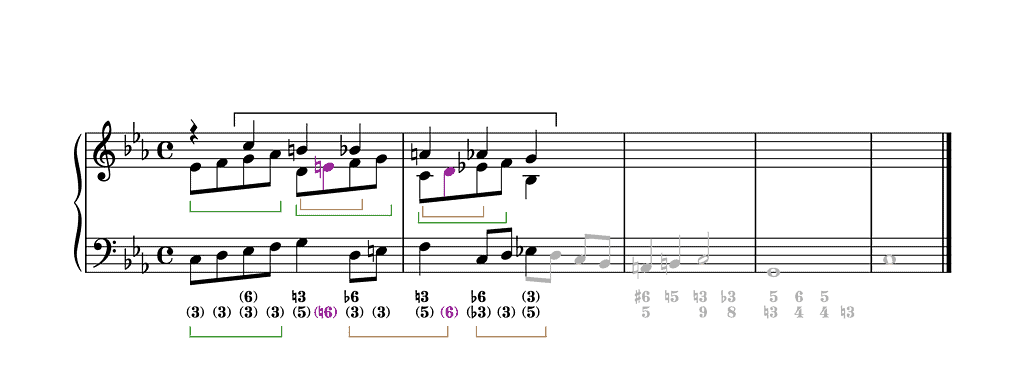

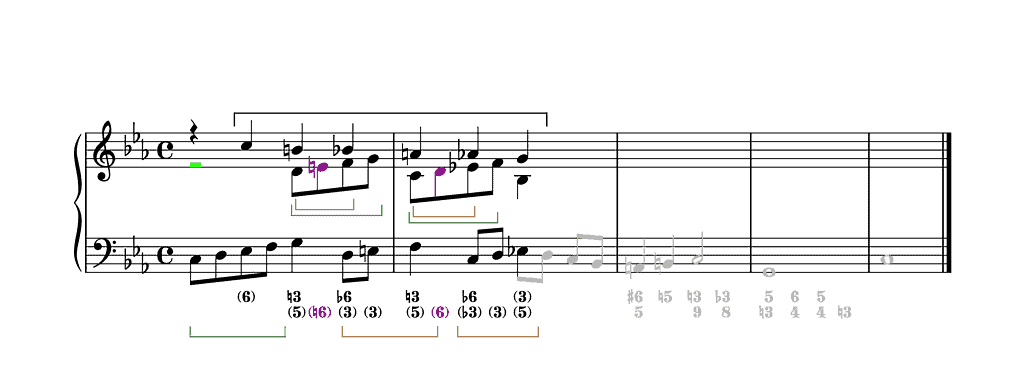

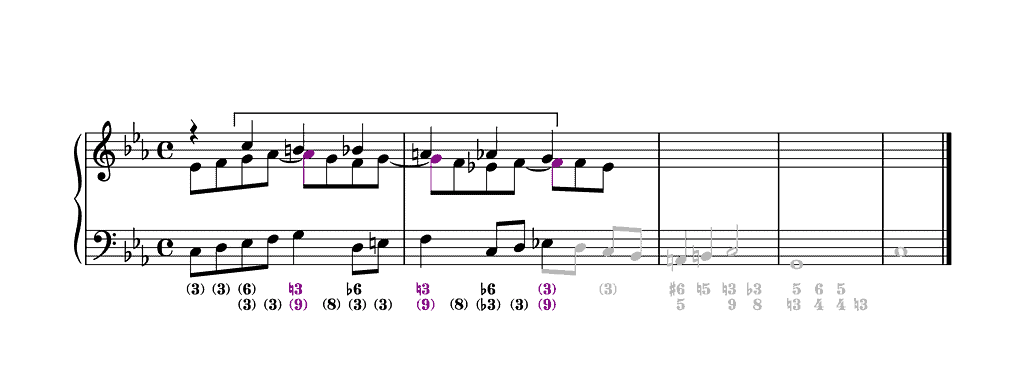

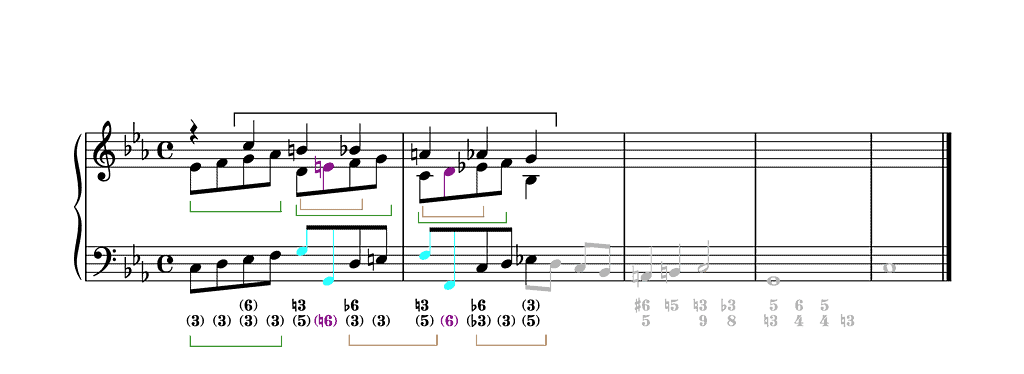

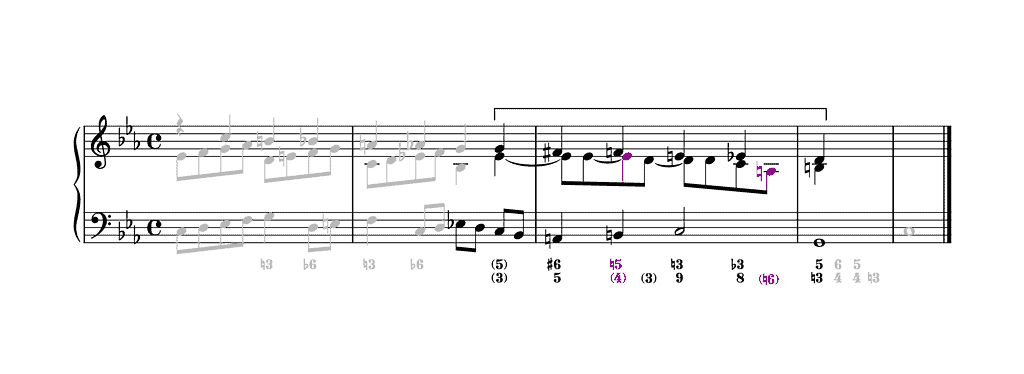

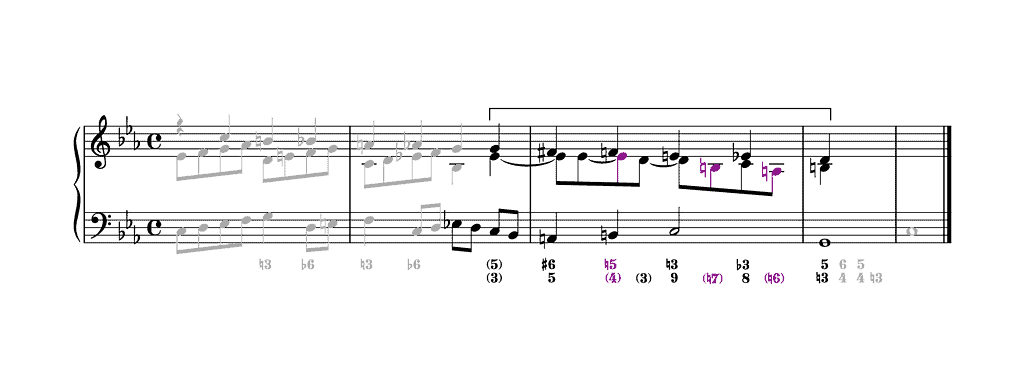

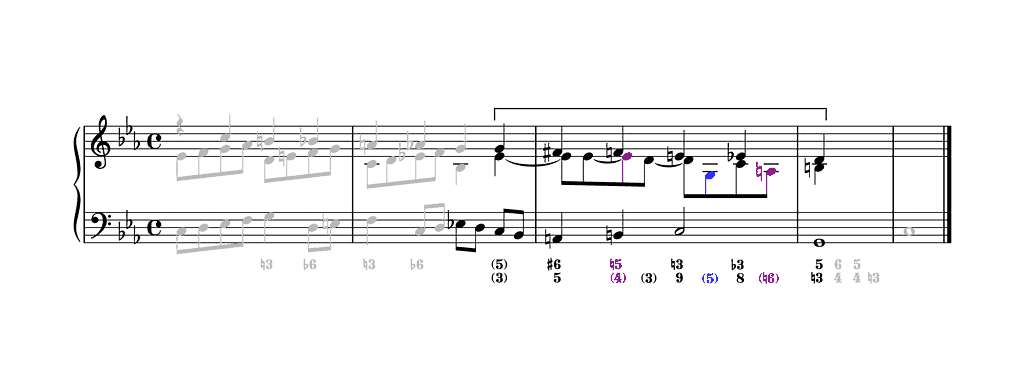

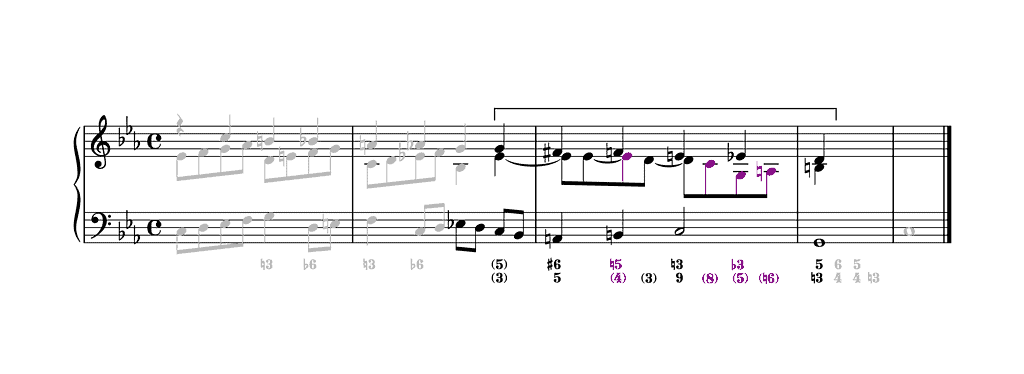

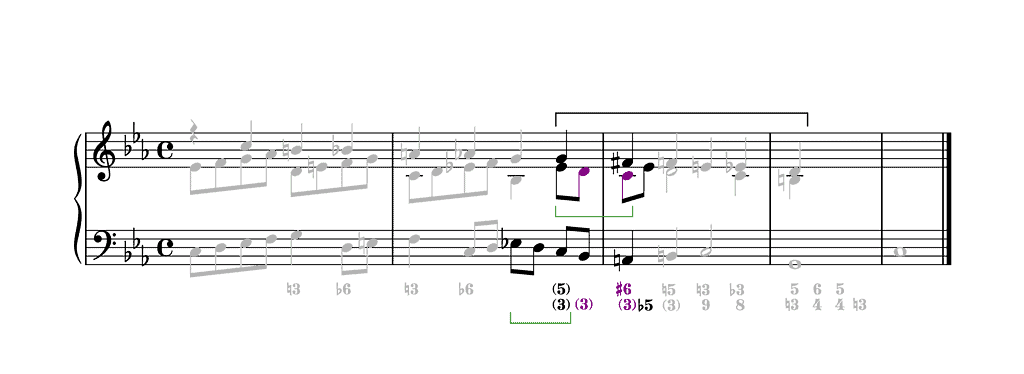

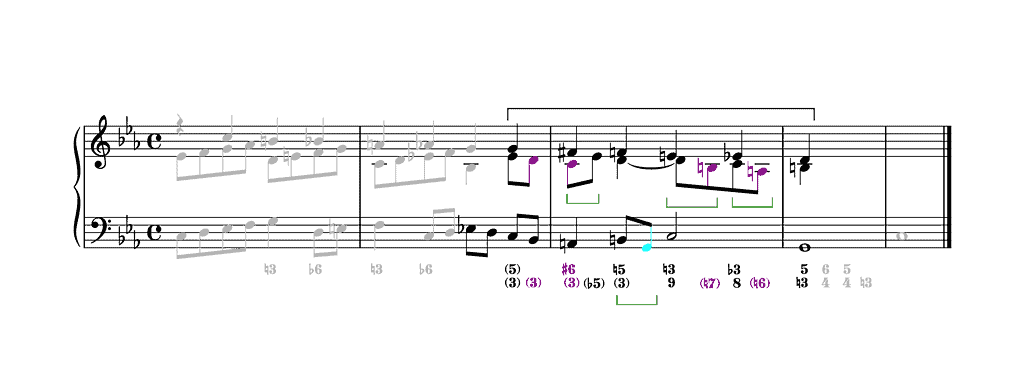

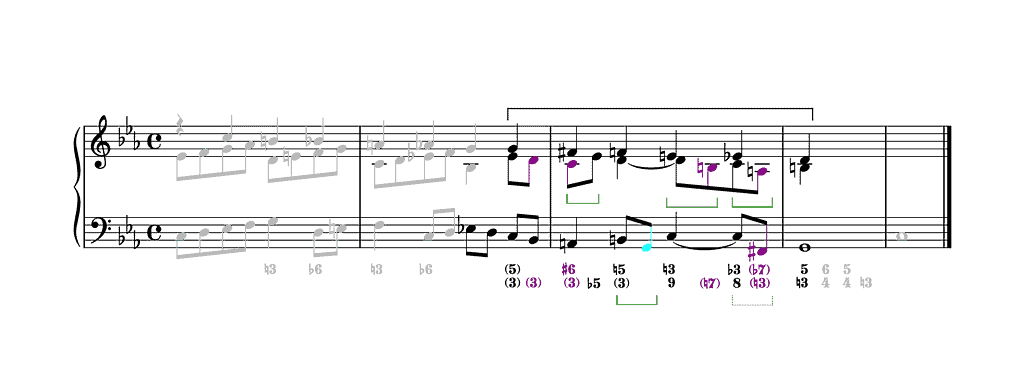

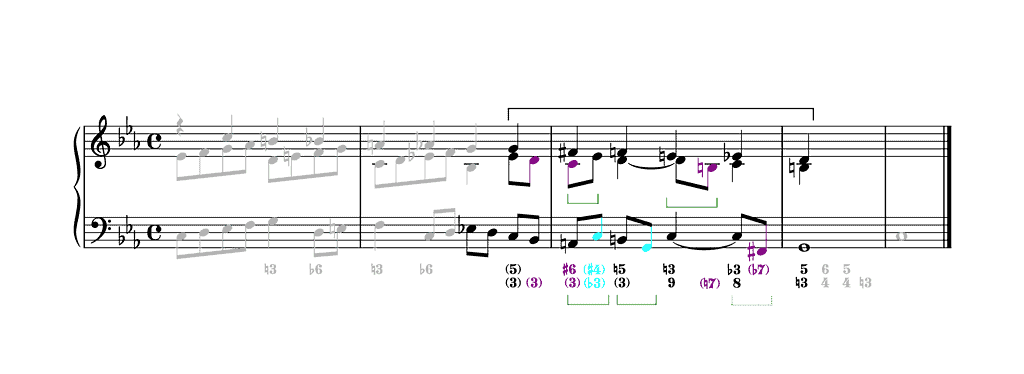

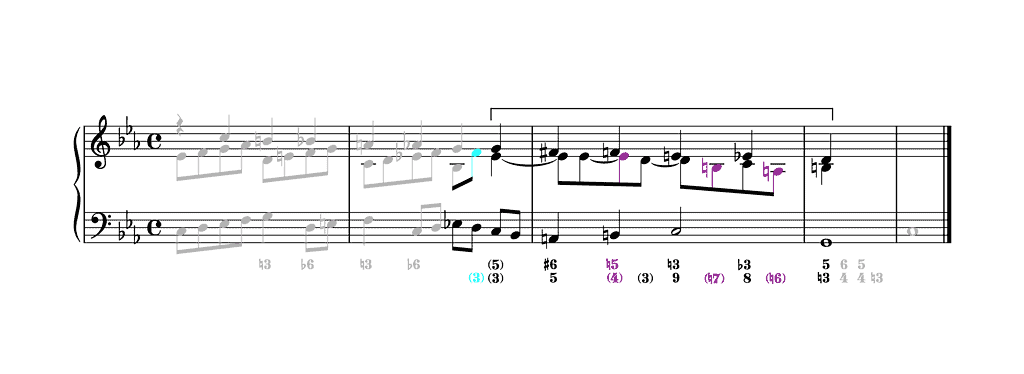

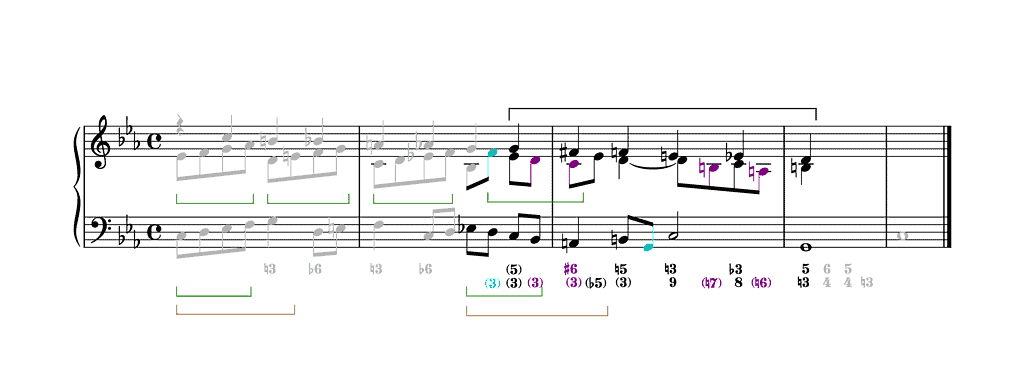

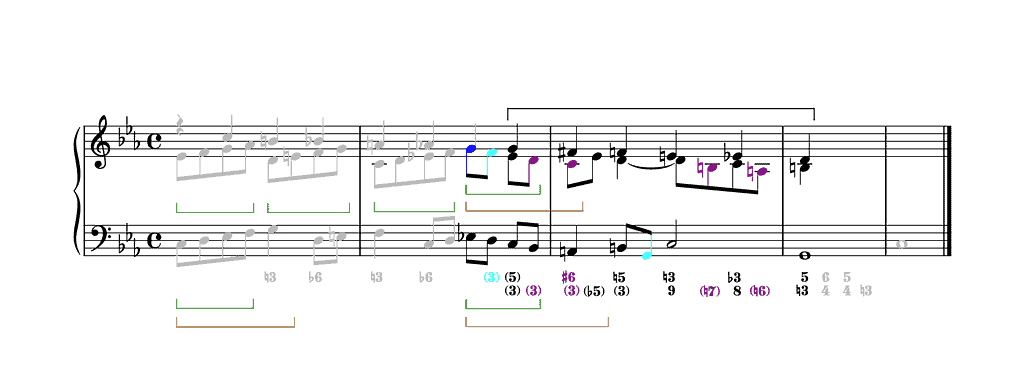

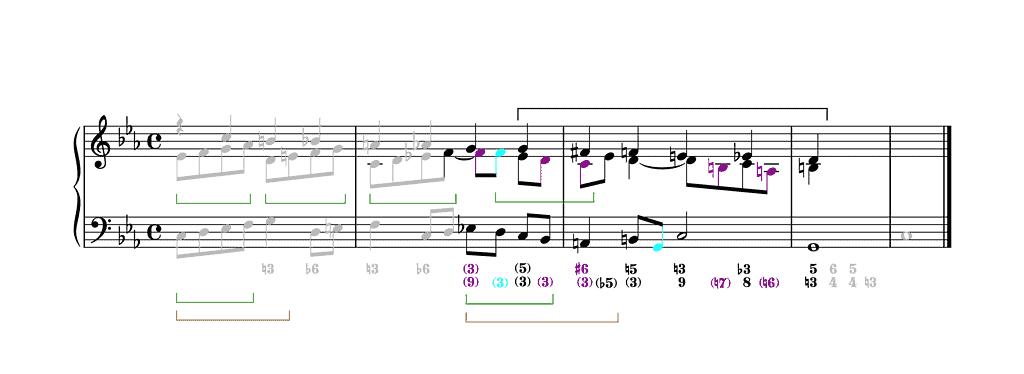

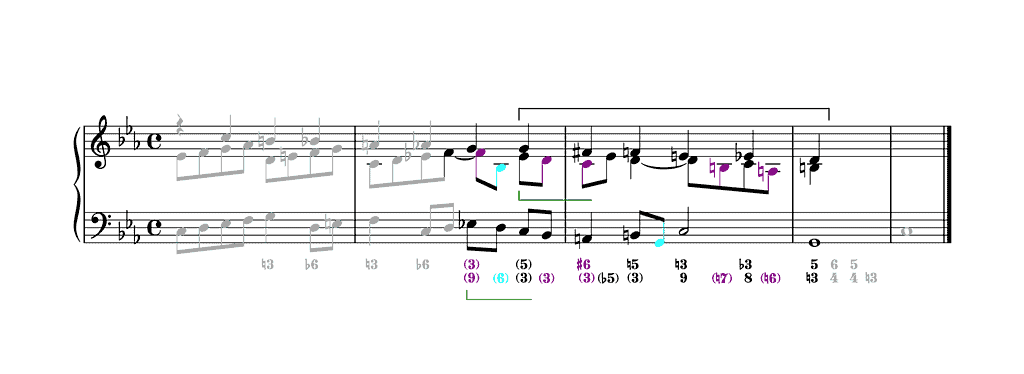

In the musical examples of this essay, I am using the following colour code:

- Purple: alternative version, changing the thoroughbass figures

- Light green: a rest replaces a note (also in the bass)

- Black hooks indicate a descending chromatic tetrachord in the top voice

- Dark green hooks indicate a recurrent motive

- Brown hooks indicate another recurrent motive

- Pink hooks indicate another recurrent motive

- Light blue: diminutions (also in the bass)

- Dark blue: something that is worthwhile looking at.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in an upper voice (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♯④ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ⑤

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Note further that

- ‘Bar 1a’ refers to the first half of bar 1, ‘bar 1b’ to its second half.

- I am using the Helmholtz pitch notation for naming musical notes. When I refer to notes without a specific register/octave, I use upper-case letters.

- In the musical examples throughout this essay, the thoroughbass figures as they appear in the 1824 edition are modified and made explicit to reflect exactly the voice leading and relative position of the upper voices.

- Thoroughbass figures between parentheses are editorial. Those in black complete the given thoroughbass figures, those in purple propose an alternative version of Mattei’s.

While I have written out all the musical examples in this essay, I strongly recommend reading only the thoroughbass figures as you play them through, only looking at the realization when in doubt. That way, you ‘think counterpoint’ instead of ‘notes’.

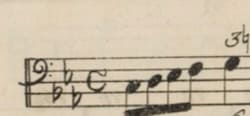

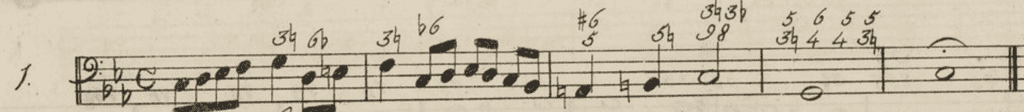

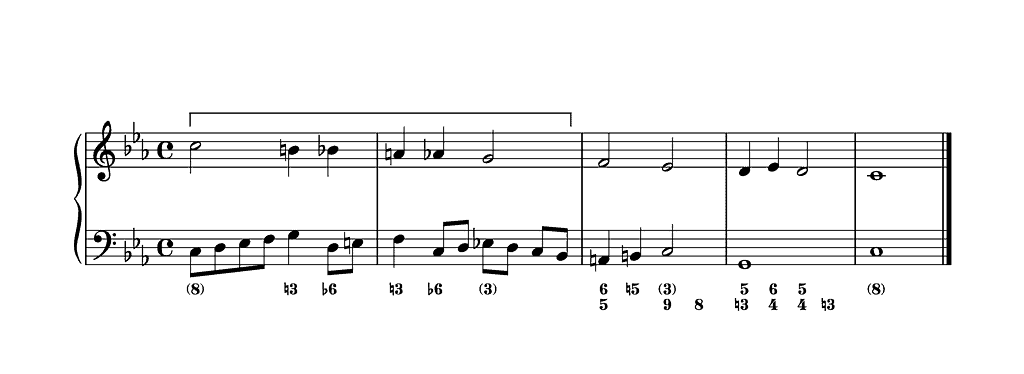

This is the unrealized first verset in C minor of Mattei from the 1824 edition:

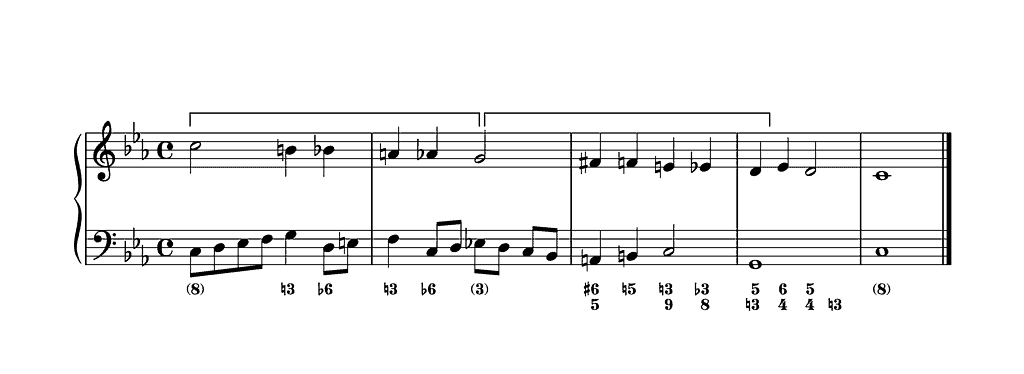

As the thoroughbass figures show, this bass potentially supports an almost completely descending chromatic scale, consisting of two overlapping descending chromatic tetrachords and a diatonic conclusion. The following example shows this in a two-part setting:

The thoroughbass figures of the 1788 autograph, however, illustrate that Mattei seems to have initially reserved the chromatic descent only for the first tetrachord, while setting the second tetrachord diatonically.

Again, the following example shows this in a two-part setting:

A good way to improve the individuality of both parts is to have the top voice start a quarter note later and to change the half note g1 in bar 2b into two quarter notes g1. That way, both chromatic tetrachords no longer overlap but follow each other, each starting on a weak beat and ending on a strong beat.

Note that in contrapuntal settings, it is usually good to have the different parts come in at different moments.

The repeated G in the top voice of bar 2b allows, should one want, to play/write the passage from the second tetrachord on an octave higher, which results in ending on the same pitch as the initial pitch c2:

Let’s now focus on adding a third voice to the fragment including the first chromatic tetrachord. The first things to note are the ⑥–⑦–① cadences in F minor (beat 4 of bar 1 and beat 1 of bar 2) and E flat major (beats 2 and 3 of bar 2). (This type of cadence is also called a clausula cantizans or a Long Comma.)

Concerning these cadences, notice how

- the middle voice progresses in parallel thirds with the bass before leaping down a fifth above the local ①; this descending melodic fifth is a common gesture above a rising step in the bass if

- its first note is set as

- a sixth chord

- a triad (a possibility in the case of a rising major second in the bass; see the ④–⑤ bass progression in the middle of bar 1)

- or a diminished triad (a possibility in the case of a rising minor second in the bass)

- its second note is set as a triad (see also my essay Mattei, Verset 1 in C Major)

- its first note is set as

- the first one —in F minor— ends with a Picardy third in the top voice on the downbeat of bar 2 due to the chromatic descent in the top voice.

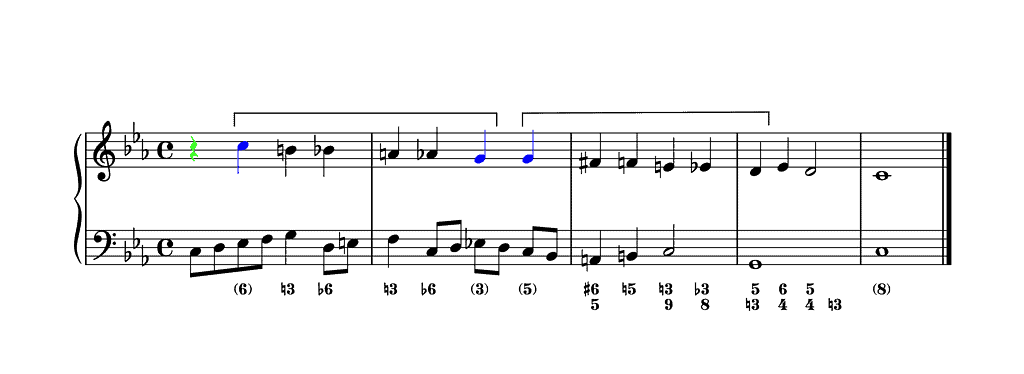

The following examples all present versions in running eighth notes. In the next one, the middle voice goes first to the doubled bass note on beat 3 of bar 1 and beats 1 and 3 of bar 2 before leaping down a fourth to the fifth of the chord (in the case of beat 3 of bar 2 to the sixth):

In the following example, the middle voice pre-imitates the bass motives of the local Long Commas, creating an interesting contrapuntal fabric with different motives, as indicated by the coloured hooks:

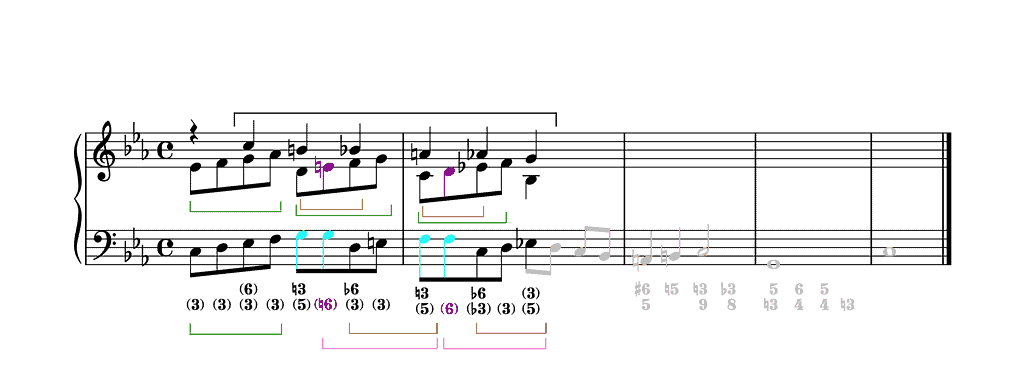

I referred above to the fact that in contrapuntal genres it is good that the parts don’t begin together. This is also the case in the next three-part example, which is identical to the previous one except for bar 1a. Instead of the middle voice running in parallel thirds with the bass, it has a half-note rest.

As such,

- the bass starts on beat 1 of bar 1

- the top voice starts on beat 2 of bar 1

- the middle voice starts

- on beat 3 of bar 1

- by imitating the bass motive of bar 1a a ninth higher.

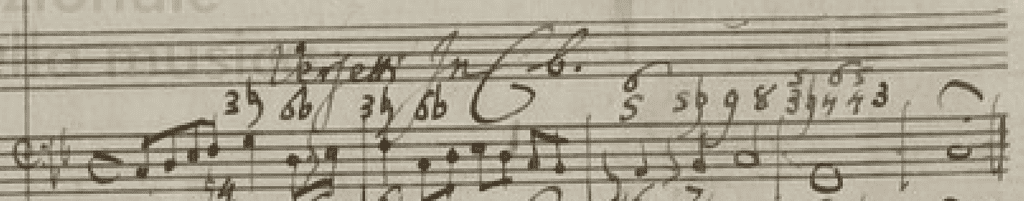

All the versions we have seen so far contain only consonant sonorities on the beats. In the next example, however, 9–8 suspensions occur on beat 3 of bar 1 and beats 1 and 3 of bar 2:

I will discuss bar 2b further below.

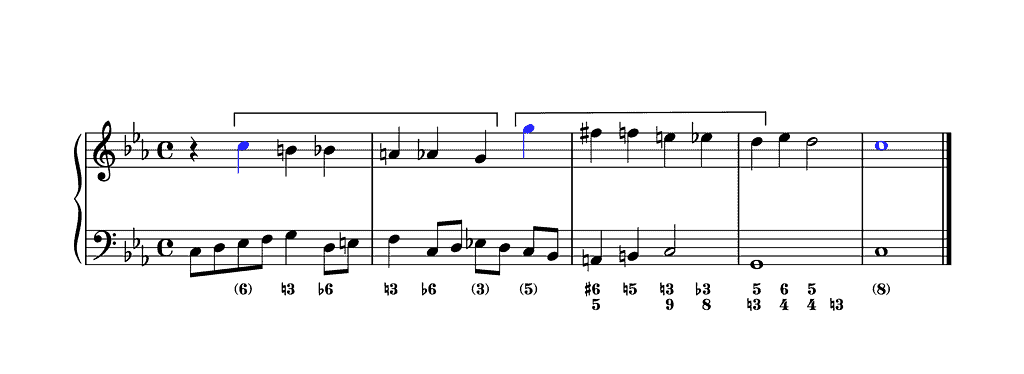

As I mentioned above, one should also explore how to vary the bass. There are many ways to do this, only a limited number of which I show.

If a walking bass in eighth notes is desired, an easy way to achieve this is to change the two quarter notes into two pairs of two eighth notes, with the even eight notes an octave lower than the uneven eight notes.

One can also just replace both quarters notes with two repeated eighth notes:

That way, a new motive, indicated by the pink hooks, can be articulated during performance.

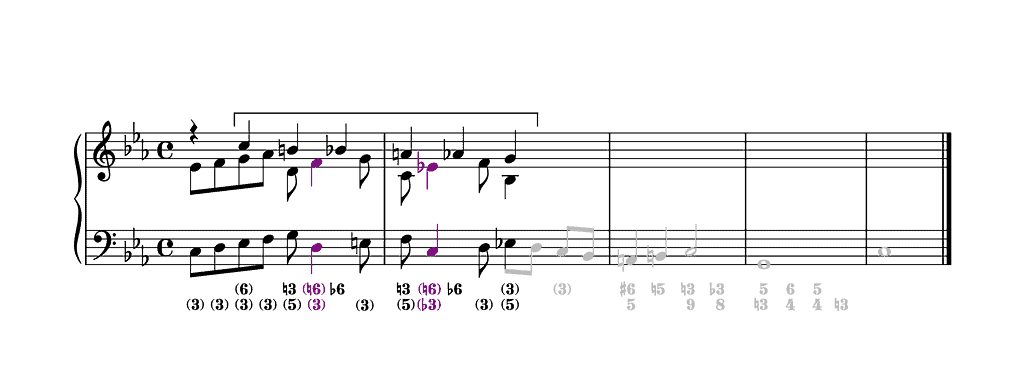

In the next version, the bass gives the ⑥ of the local Long Commas an eighth note earlier, creating twice a syncopation:

Notice how

- the middle voice and the bass are engaged in a homorhythmic texture

- the running eighths are preserved, albeit not in once voice.

In the following version, a different kind of syncopation occurs in the bass, filling the gap of the descending melodic third and creating a 4/2 sonority on the moment of syncopation:

Notice how the middle voice produces alternating rising fourths and descending fifths. This is a common upper part when the bass produces alternating descending thirds and rising seconds. (In its simplest form, the first bass note of each segment of this moto del basso is set as a triad, the second note as a sixth chord. For more information on this moto del basso see my essay Disjunt Moti del Basso.)

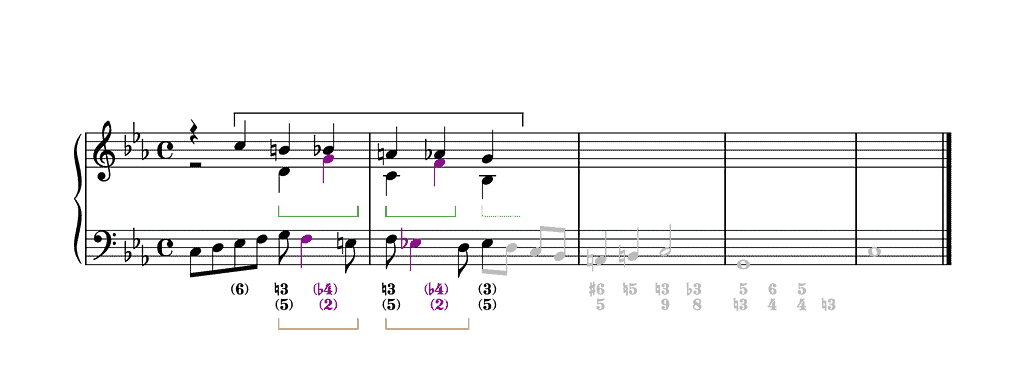

Let’s now look at the bass line during the first three beats of bar 1. To embellish the rising melodic fifth c–g, Mattei opts for the obvious solution by inserting each note of the scale that lies in between them. There are other options, however. One of those —an important one— is what I call ‘overshooting the goal and reaching it from behind’. Consider the following example.

Instead of rising stepwise from c, the bass immediately leaps up an octave to c1, which is a fourth higher than the goal g. To compensate for this, the bass then descends stepwise from c1 to g via b♭ and a♭. (This creates a suspirans, indicated by the pink hook. For more information on the suspirans see my essay Mattei, Verset in C Major.)

The bass of this specific version could also start with an eighth note rest, making the suspirans even more prominent:

The overshoot can also be more modest. Instead of leaping up an octave, the bass could leap up a minor sixth, to a♭, only half a step higher than g. This a♭, being ♭⑥, must descend and is followed by the prematurely reached goal g and an f♯ on beat 2. This f♯ is in turn followed by the actual goal g, which is thus reached ‘from in front’, that is, from below:

Note that I have used the version with the syncopated bass motives in bars 1b and 2a but obviously these alternative beginnings in the bass are compatible with any version (of the bass).

Practice Tip

Since the upper voices in all the settings of the first fragment are invertible, make sure to practice these settings in both registral positions. (I didn’t include musical examples with inverted upper voices to reduce the number of examples in this essay.)

As I wrote above, there are many more ways to vary this fragment, both in the upper voices and in the bass, but for now let’s move on to the second fragment.

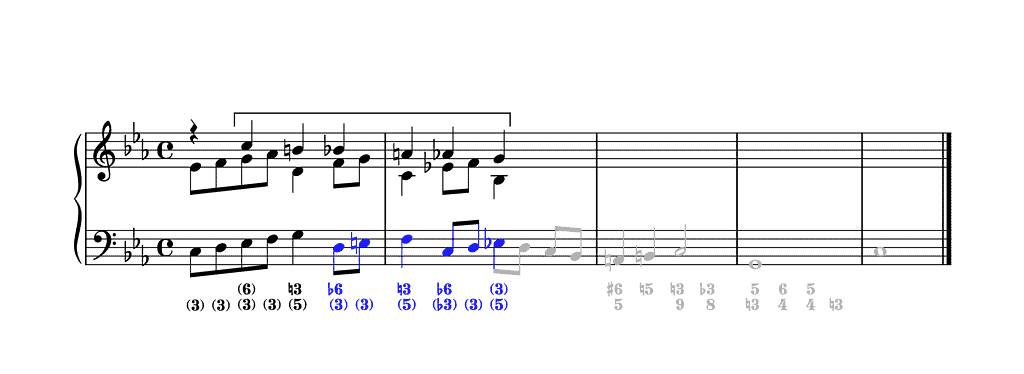

The following example makes Mattei’s thoroughbass figures of the second fragment explicit:

It is interesting to observe that both in the 1788 manuscript and the 1824 edition, the eighth notes in the bas in bar 1a are beamed per four, while those in bar 2b are beamed per two. Although one might dismiss that as coincidence, I rather believe this notational difference is intended and refers to harmonic rhythm and choice of chords. On both beats of bar 1a, the intended harmony is C minor. In bar 2b, however, two chords seem to be intended: an E flat major triad on beat 3 and a C minor triad on beat 4.

The previous example can be easily converted into a version in running eighth notes by repeating the dissonances that occur in the middle voice on the weak eighth notes.

Note how

- the first repeated dissonance (second eighth note of beat 1 of bar 3) prepares a new suspension (beat 2 of bar 3)

- the incomplete neighbour note a (second eighth note of beat 4 of bar 3) is quite efficient to lead into the penultimate bar.

Instead of ornamenting the 9–8 suspension by simply repeating the 9 on the weak eighth note, one can also opt to insert ♮7 or 5:

Another option to obtain running eighth notes is to resolve the 9 on the second eighth note of beat 3 of bar 3, which is then followed by two eighth notes g and a♮, respectively, on beat 4:

In the following example, the middle voice doesn’t prepare the dissonant e♭1 on the downbeat of bar 3 but rather walks in parallel thirds with the bass, giving that e♭1 only on the second eighth note of beat 1:

Note how the middle voice imitates the bass at the octave, indicated by the dark green hooks.

The motive of a leaping third that appears in the middle voice on the downbeat of bar 3 can be used on every beat in that bar, creating a beautiful motivic coherence:

Another leaping interval can be added to the contrapuntal fabric by inserting an F♯ in the bass as the last eighth note of bar 3, enhancing the impact of the final cadence:

One can also opt for a quarter note c1 in the middle voice on beat 4 of bar 3, creating a vertical diminished fifth with the F♯ in the bass:

Note that beat 1 of bar 3 in the bass has been embellished, adding a leaping third to the setting.

Let’s now focus on the end of the first tetrachord and on the junction between the two tetrachords in bar 2b. The middle voice in all the examples above always has a quarter note b♭ on beat 3 followed by a quarter or eighth note e♭1 on beat 4. However, there are other, contrapuntally interesting versions of those beats. First, one could insert an f1 on the second eighth note of beat 3, creating parallel thirds with the bass:

Secondly, one could continue the parallel thirds between the middle voice and the bass until the downbeat of bar 3:

Notice

- the suspirans in the middle voice (dark green hook) created in his way (for more information on the suspirans see my essay Mattei, Verset in C Major)

- how this suspirans is related to the other motives in the middle voice and the bass (dark green and brown hooks)

- how the quarter note B♮ in the bass on beat 2 of bar 3 has been transformed into two eighth notes B♮–G.

Thirdly, the parallel thirds with the bass could even start an eighth note earlier, with both upper voices giving a unison g1 on beat 3 of bar 2:

Fourthly, one could add a 9–8 suspension to the middle voice in bar 2b, treating the fourth eighth f1 in bar 2a as its preparation:

Since the preparation of the ninth lasts here only an eighth note, the rhythmic value of the tied note cannot be longer than an eighth note. So, even if the actual suspension lasts a quarter note, the fact that it is split into two eighth notes, the first tied, the second articulated, makes this voice leading fine.

As we saw above, before resolving, a 9 can also be embellished by a descending melodic fifth:

Thanks to this embellishment, the imitation at the octave between the bass and the middle voice becomes more prominent (dark green hooks).

Practice Tip

The upper voices in all the settings of the second fragment are again invertible, so make sure to practice these settings in both registral positions.

For possibilities on how to realize the final cadence see my essay Mattei, Verset 2 in C Major.

Via the link below, you can listen to a realization of Mattei’s first versetto in C minor:

Select Bibliography

Byros, Vasili. Mozart’s Vintage Corelli: The Microstory of a Fonte-Romanesca, in: Intégral 31 (2017), 63–89.

Demeyere, Ewald. Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue — Performance Practice Based on German Eighteenth-Century Theory (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2013).

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207–229.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).