This essay is the first of a series devoted to how the versets (i.e. short partimenti) by Stanislao Mattei (1750–1825) can be realized at the keyboard.

The versets by Mattei are intended to be realized in three parts with great concern for contrapuntal quality. Typically, instead of focusing on just one realization, students had to explore as many options as possible.

In the musical examples of this essay, I am using the following colour code:

- Red: questionable voice leading

- Orange: voice leading that is more or less/almost okay

- Purple: alternative version in relation to the thoroughbass figures

- Light green: a rest replaces a note

- Light blue: diminutions (also in the bass)

- Brown hook: indication of an imitation in melodic inversion (this means that the interval directions of the regular version are reversed in the inverted version; for instance, an ascending third in the original version becomes a descending third in the inverted version)

- Dark blue: something that is worthwhile looking at.

Note that ‘bar 1a’ refers to the first half of bar 1, ‘bar 1b’ to its second half.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in an upper voice (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Note further that I am using the Helmholtz pitch notation for naming musical notes. When I refer to notes without a specific register/octave, I use upper-case letters.

While I have written out all the musical examples in this essay, I strongly recommend reading only the thoroughbass figures as you play them through, only looking at the realization when in doubt. That way, you ‘think counterpoint’ instead of ‘notes’.

This essay is an expanded version of the lecture I gave during the international conference Musicianship in Development held at the Antwerp Conservatoire on 23 and 24 November 2023. My lecture can be seen here:

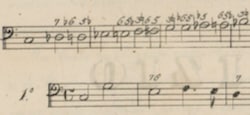

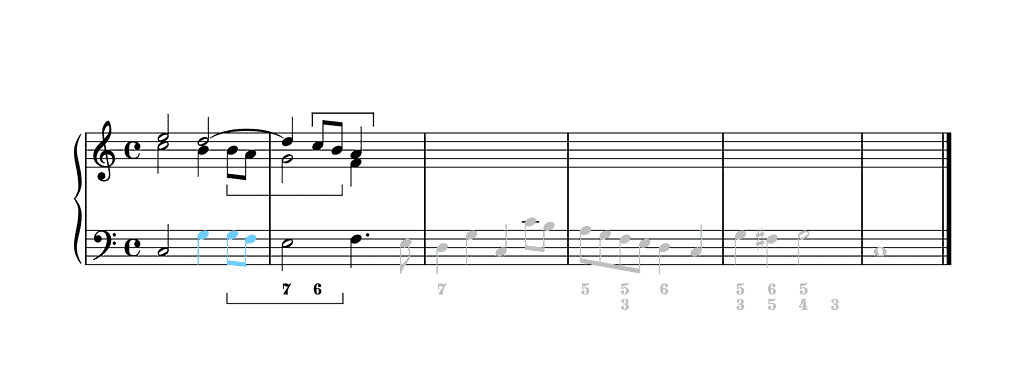

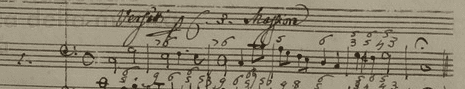

This is the unrealized first verset in C major of Mattei:

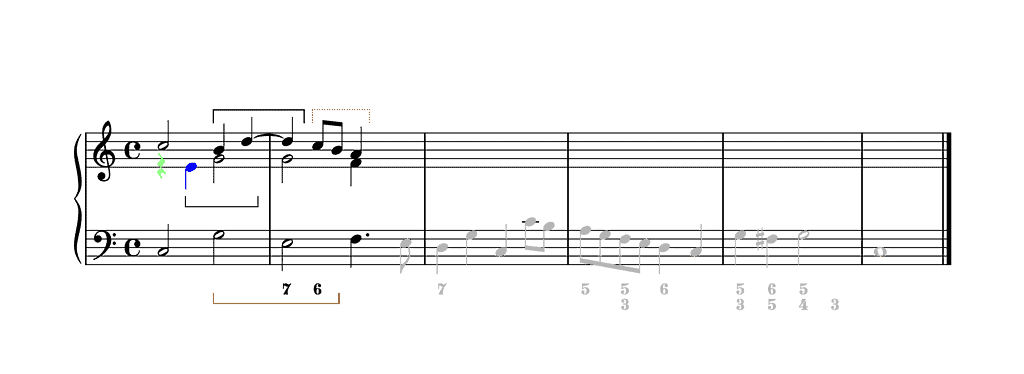

I will discuss in detail the contrapuntal possibilities of this verset and do so fragment per fragment, starting with the first two bars. A potential voice-leading issue appears from bar 1 to 2.

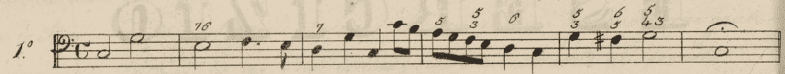

On the one hand, the seventh on e in the bass (bar 2a) needs to be prepared since it is a non-essential dissonance. This means that a D should be present above the g in the bass (bar 1b), the D being the (consonant) fifth of the triad. On the other hand, the leading note should normally rise to the tonic, which isn’t possible in this case because of the presence of the D. This implies that the leading note should leap down to ➎, the third on the bass note e, a voice leading that is not ideal.

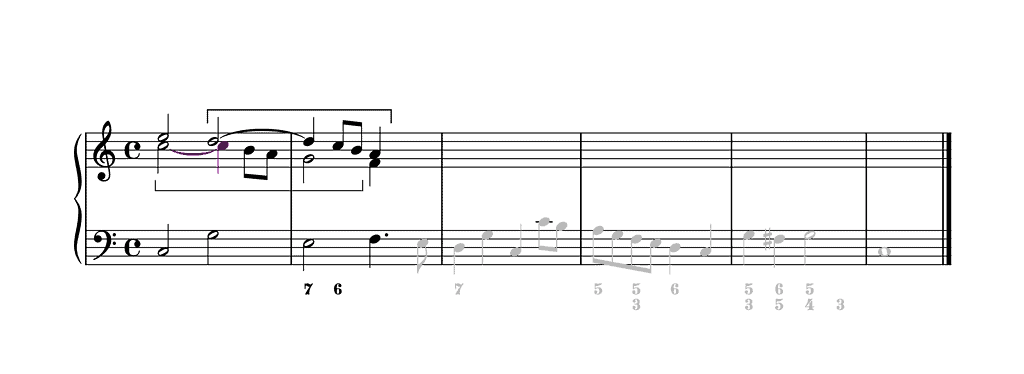

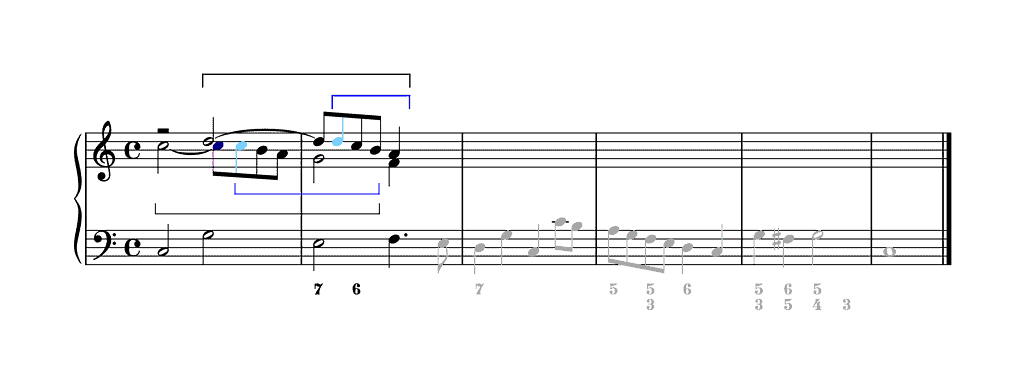

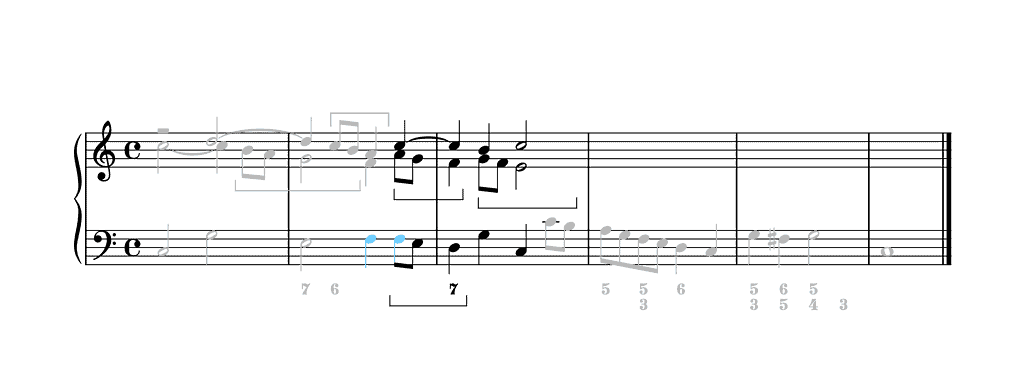

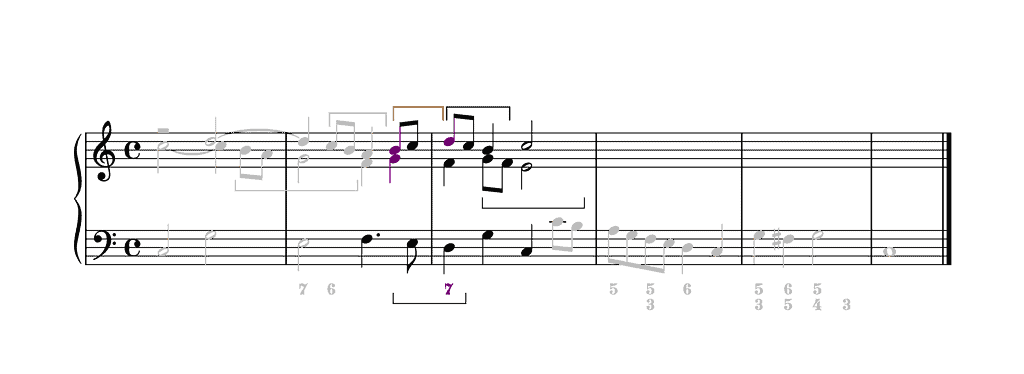

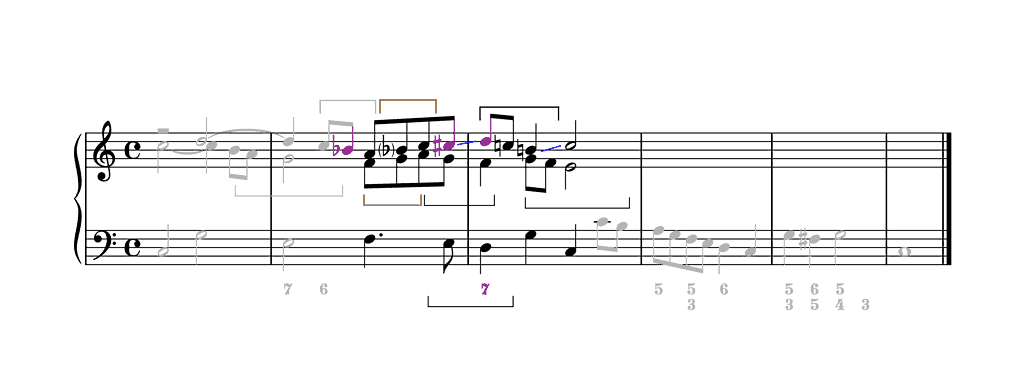

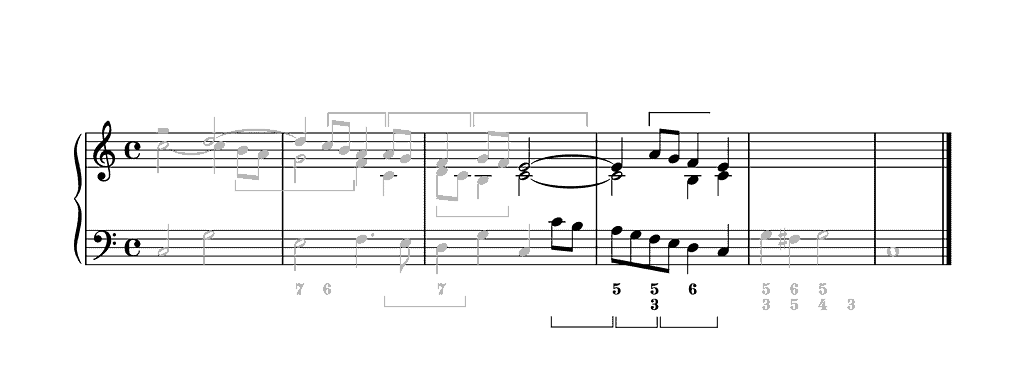

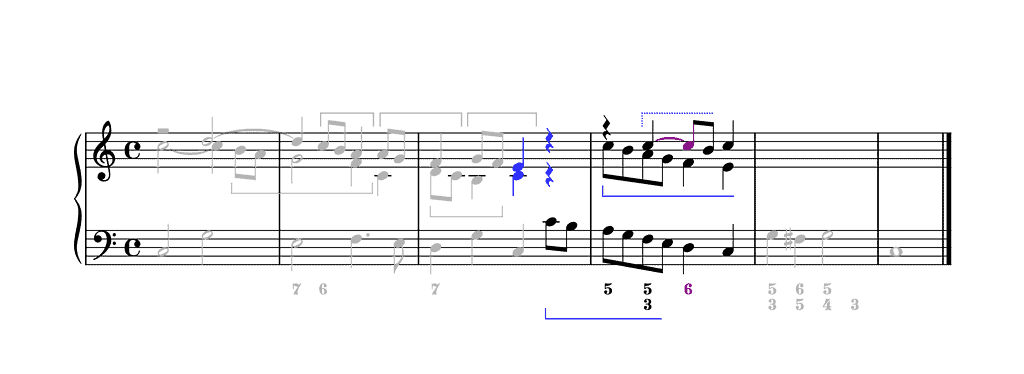

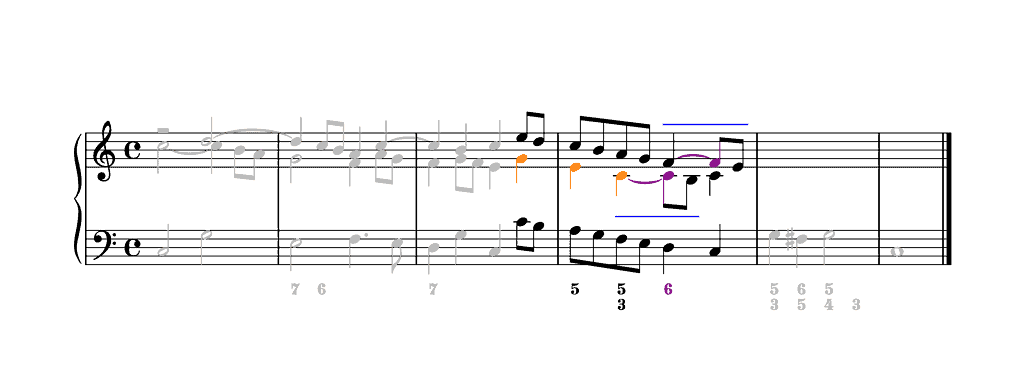

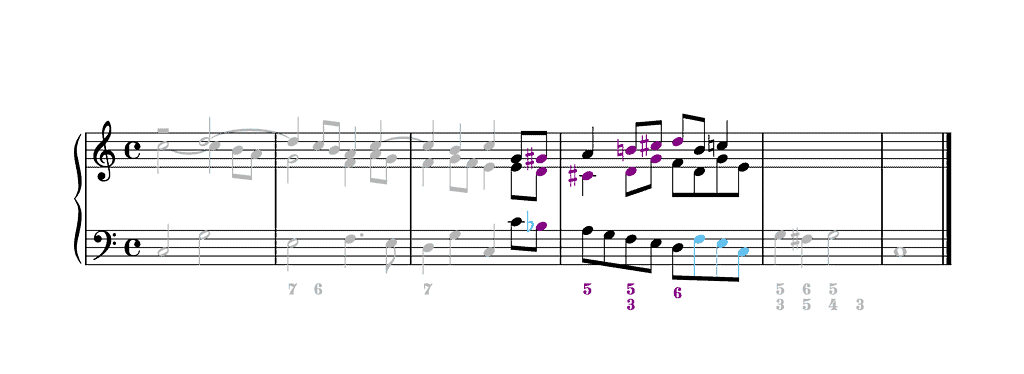

A possible way out of the ‘leading-note issue’ is by giving melodic sense to the descending ➐ by adding a passing note ➏ in between ➐ and ➎:

In the example above, the half note b1 has been transformed into a quarter note b1 followed by two eighth notes b1 and a1. As such, a three-note stepwise descending motive appears that can be imitated by the top voice half a bar later.

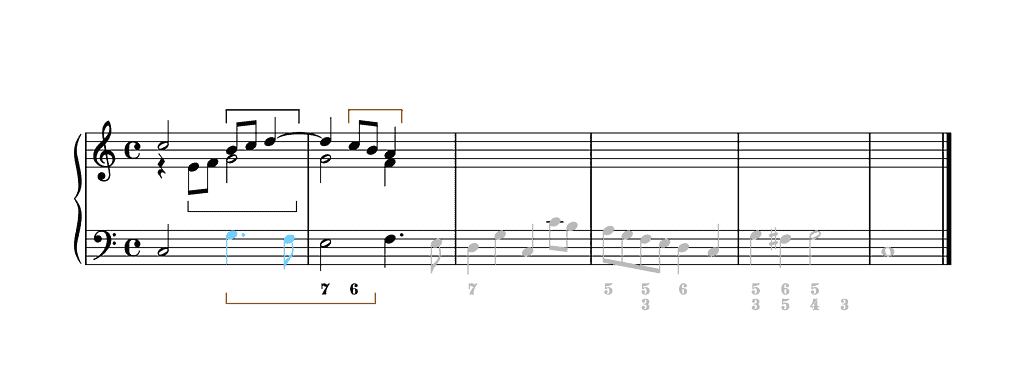

By similarly transforming the second note in the bass, the presence of this motive becomes even more compelling as it appears simultaneously in the middle voice and the bass:

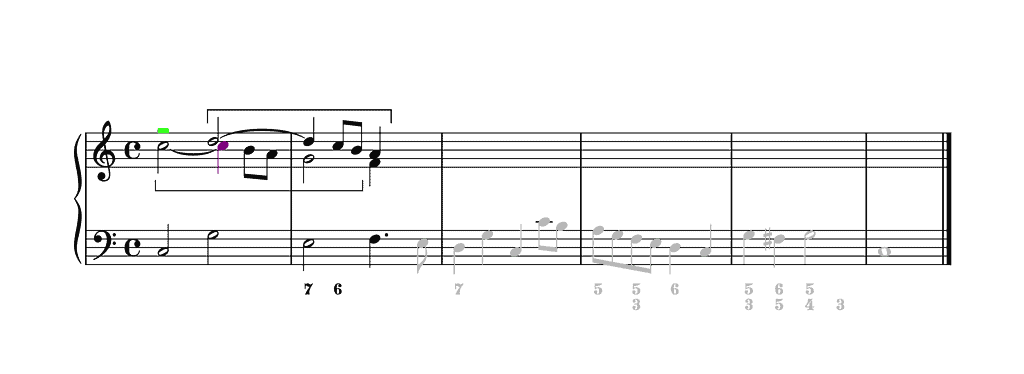

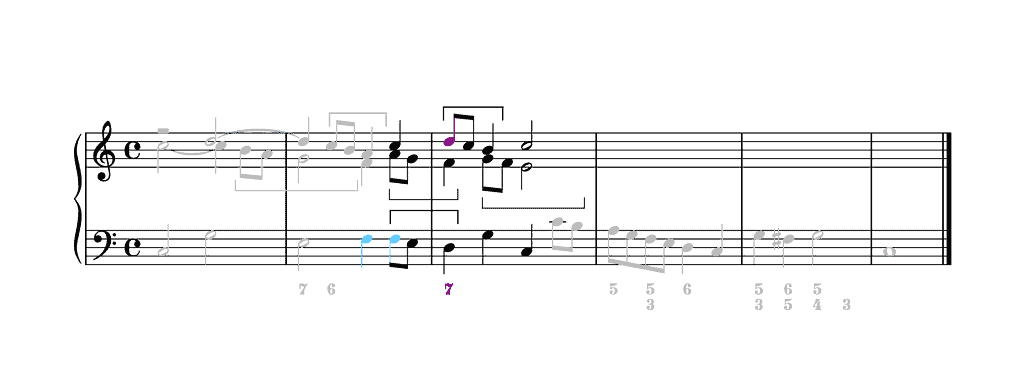

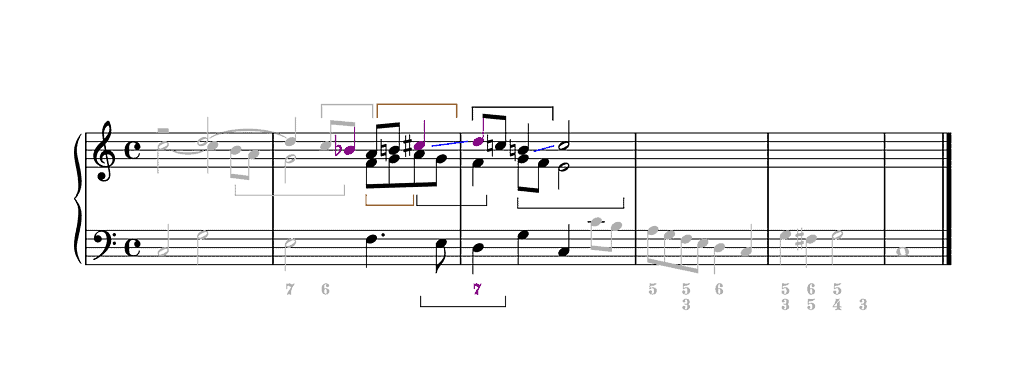

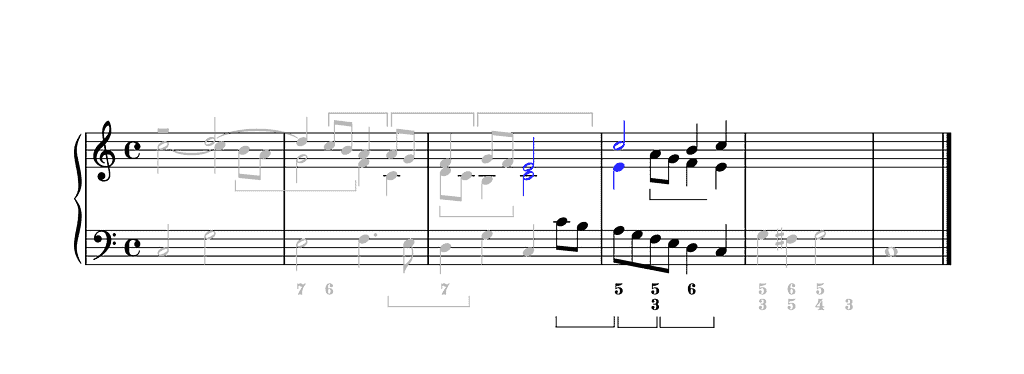

Having studied the three basic partimento cadences (for more information on these cadences see my essay Cadences: The Basics), a student is well aware of harmonic rhythm and how dissonances can be used to make a bass note that is too long to be set only with one chord/sonority more interesting. Consider the half note g in the bass in bar 1b. The standardized harmonic rhythm in a 4/4 time signature is a quarter note. (Note that this is only a general guideline and very soft rule; you will find many exceptions.) Since this g is ⑤, the link with the cadenza composta, a cadence in which ⑤ lasts two beats, is obvious. In this case, the first-choice realization is to postpone the third of the chord, ➐, and temporarily replace it with ➊, a voice leading that results in a 4–3 suspension:

As you can see in the example above, thanks to this added suspension, which is not specified in the thoroughbass figures, a canonic imitation of a more extended motive appears between the middle and the top voices.

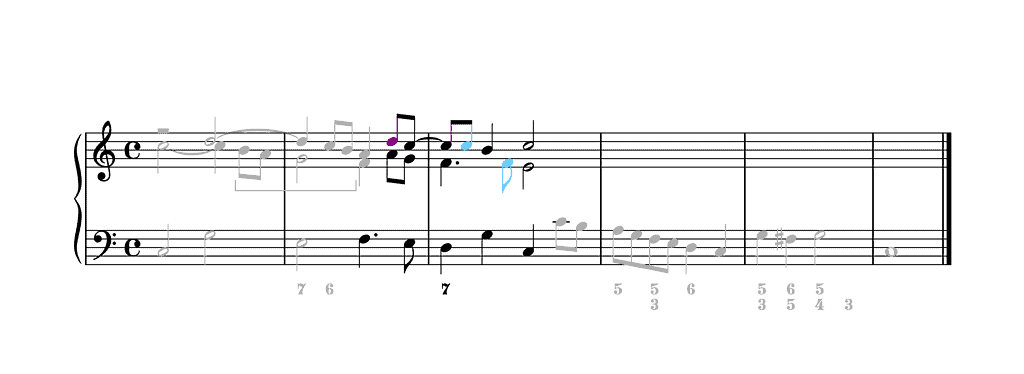

To make this imitation stand out a little more, one could replace the half note e2 in the top voice in bar 1a by a rest:

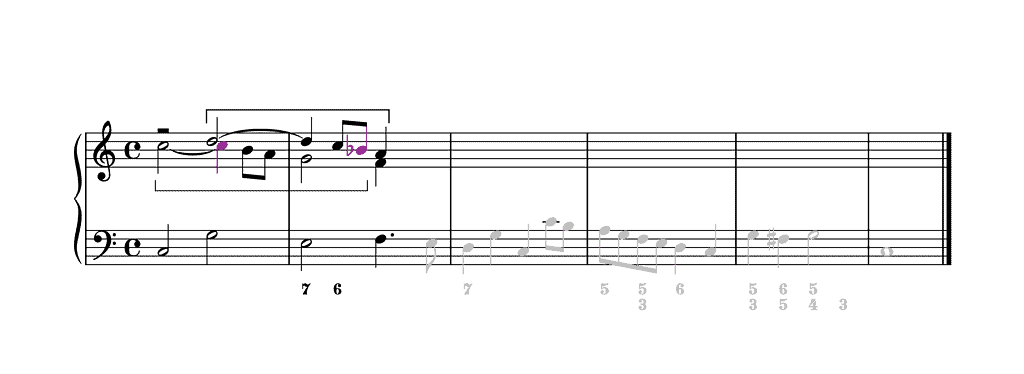

Have a look at the bass in bar 2 now. Since the interval e-f is a half note, this offers the possibility for a temporary glance at F major. This implies that e-f functions as a ⑦–① snippet in that key and that the third note in the upper voice in bar 2 should be lowered chromatically (b1 becomes b♭1):

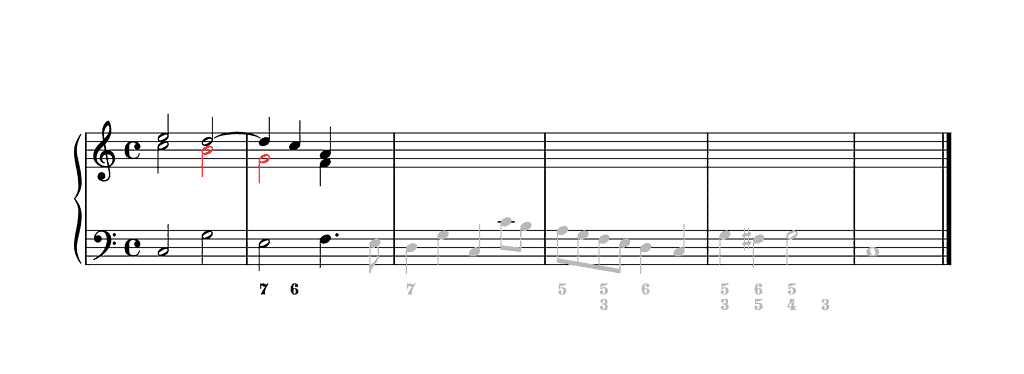

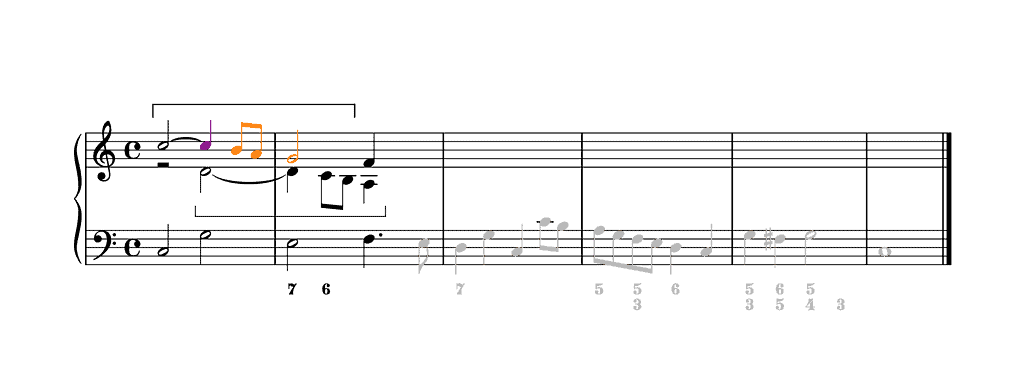

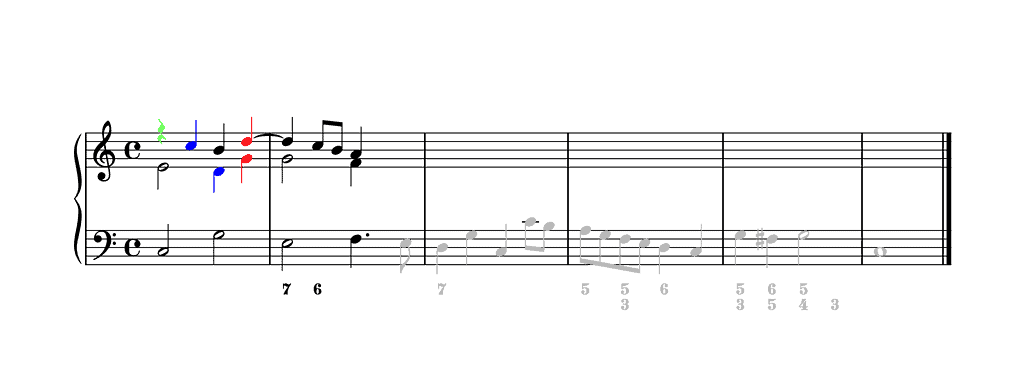

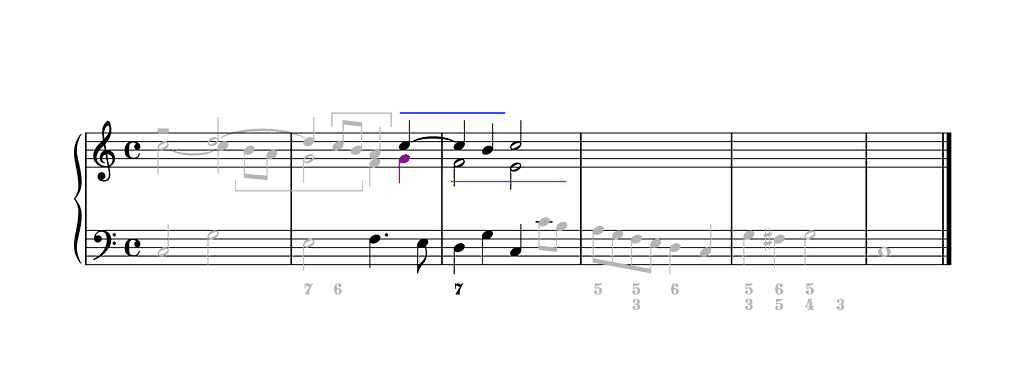

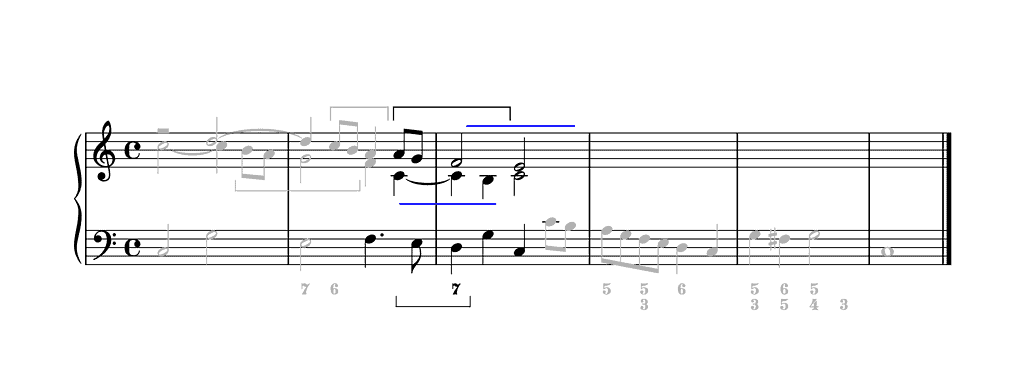

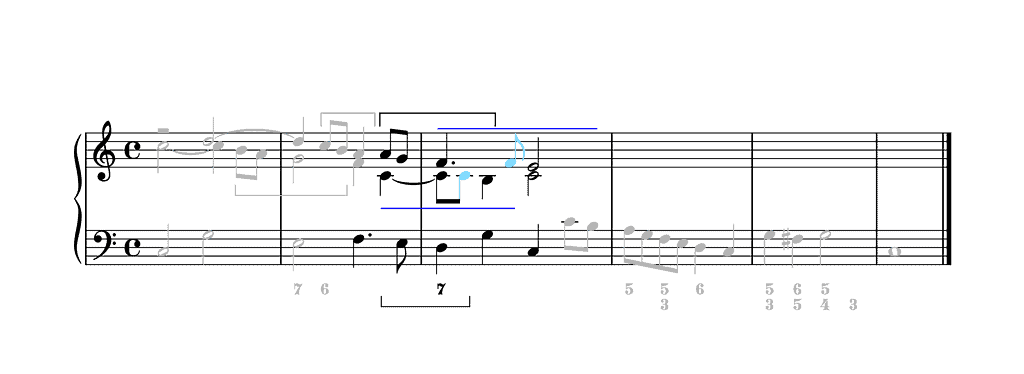

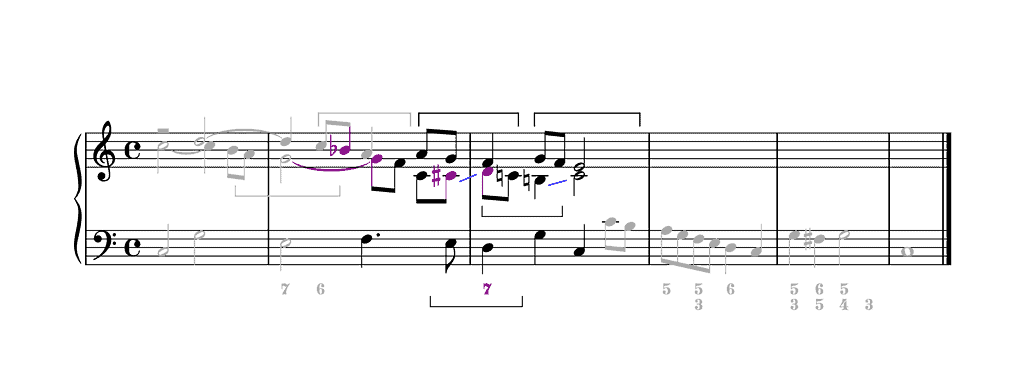

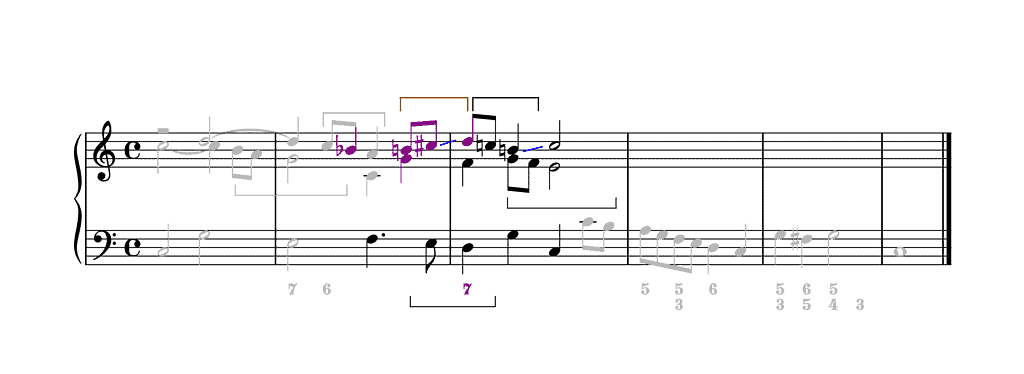

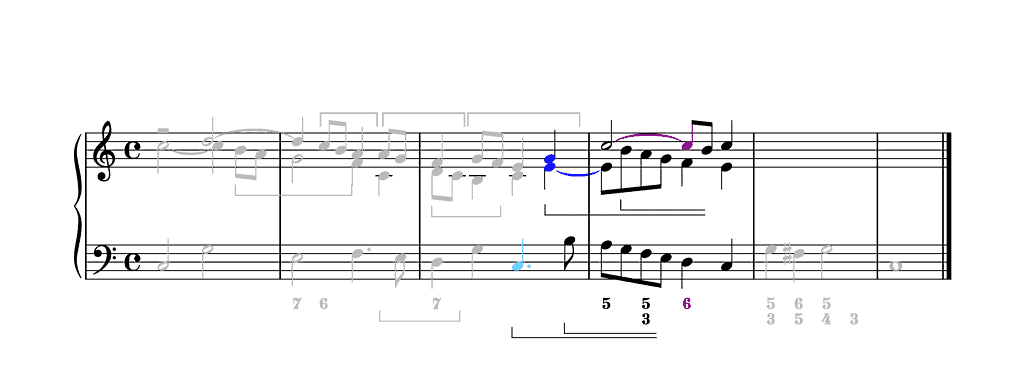

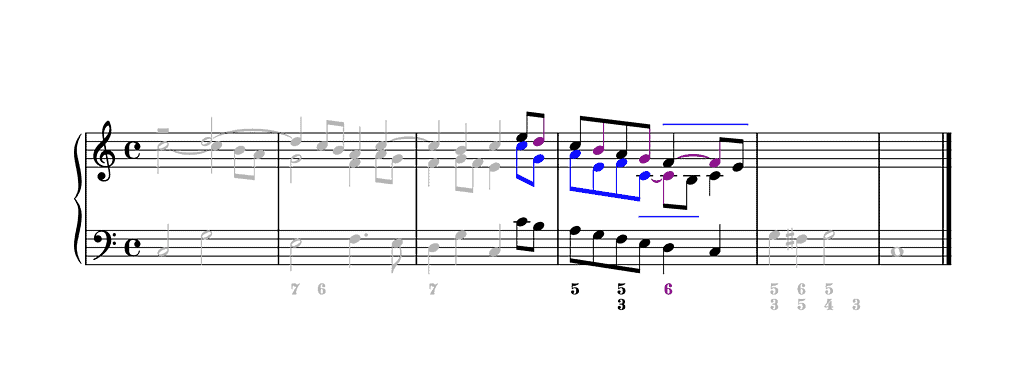

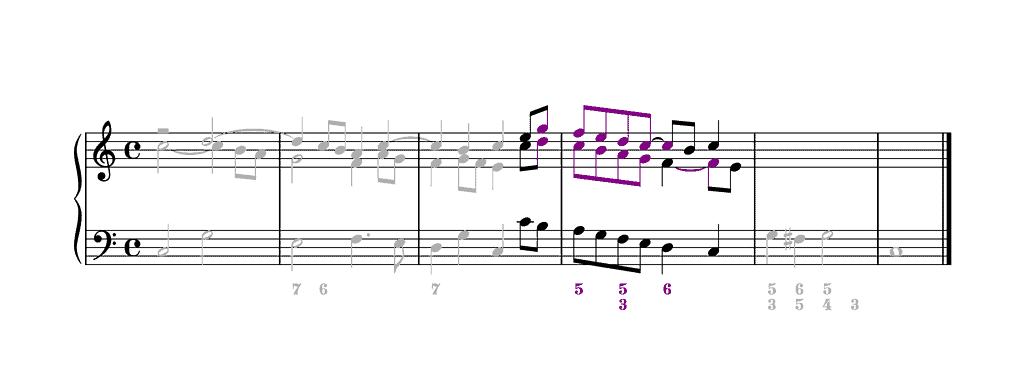

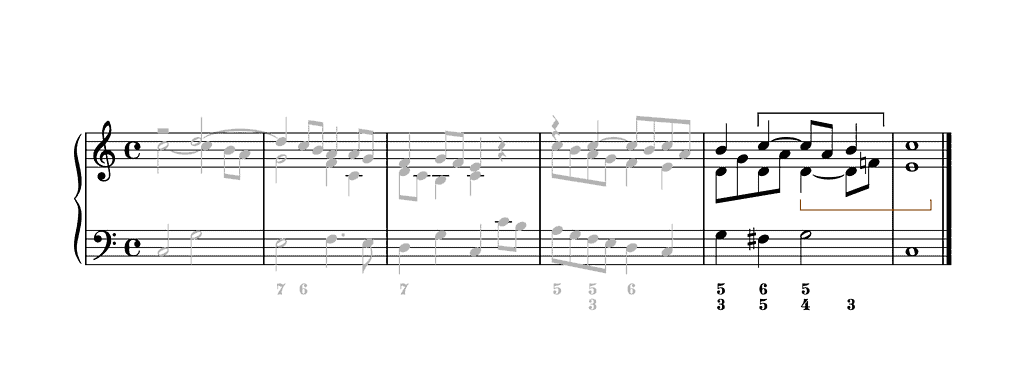

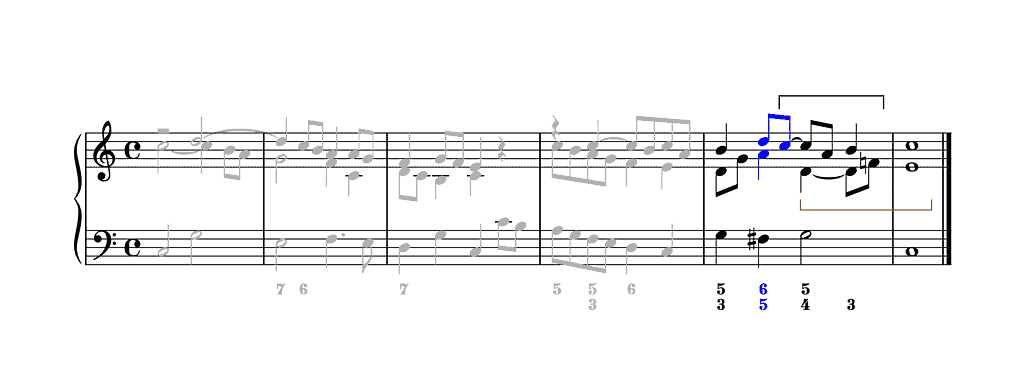

If one prefers more rhythmic drive, one could opt for running eighth notes that start in the middle of bar 1. A simple way of achieving this is to change each quarter-note suspension into an eighth-note suspension that is followed by an eighth-note repetition of the suspension:

As such, a four-note motive called a suspirans arises. I have bracketed this motive in the example above in blue. A suspirans has the following features:

- It consists of four notes

- It consists of three successive steps, at least the first two of which are in the same direction

- The first three notes have the same note value

- The first note starts on a weak beat or part of a beat

- The last note has the best metric value.

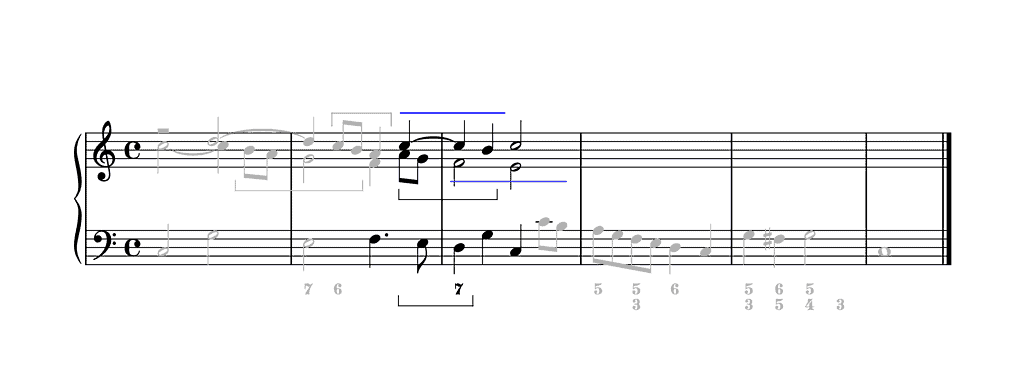

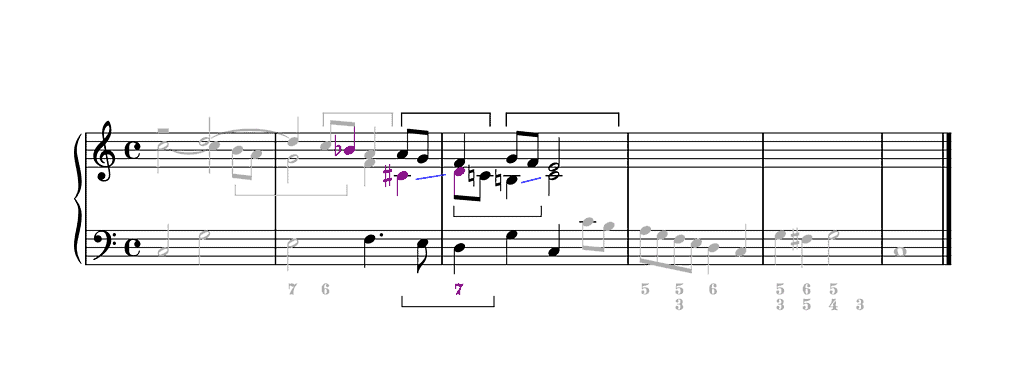

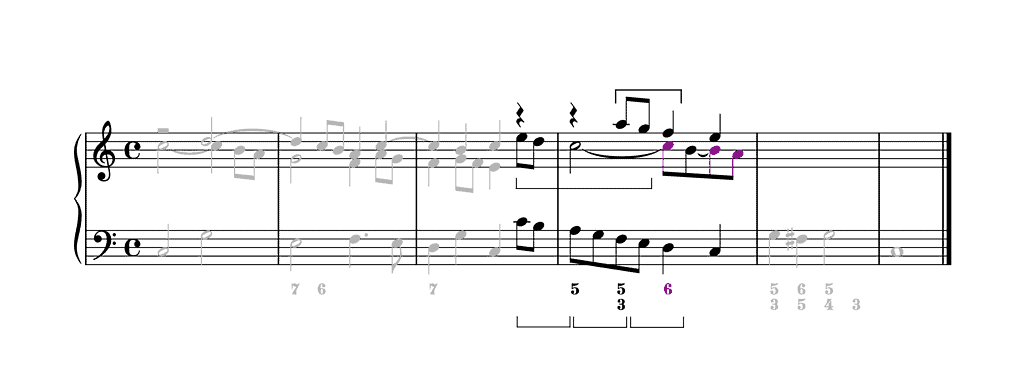

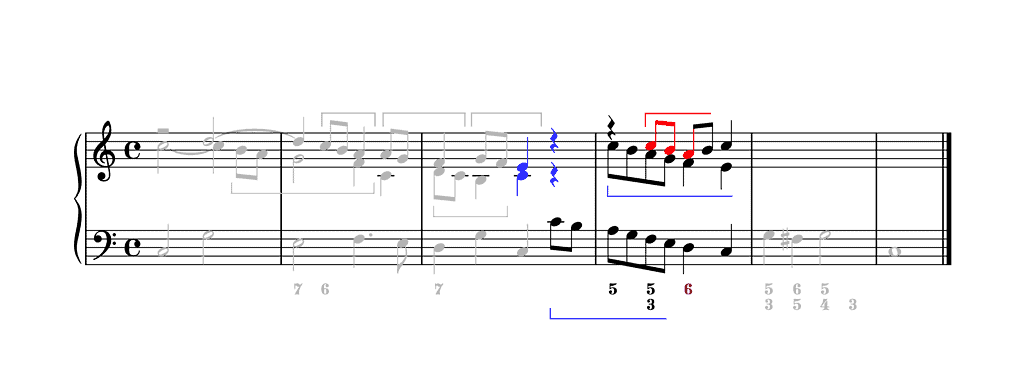

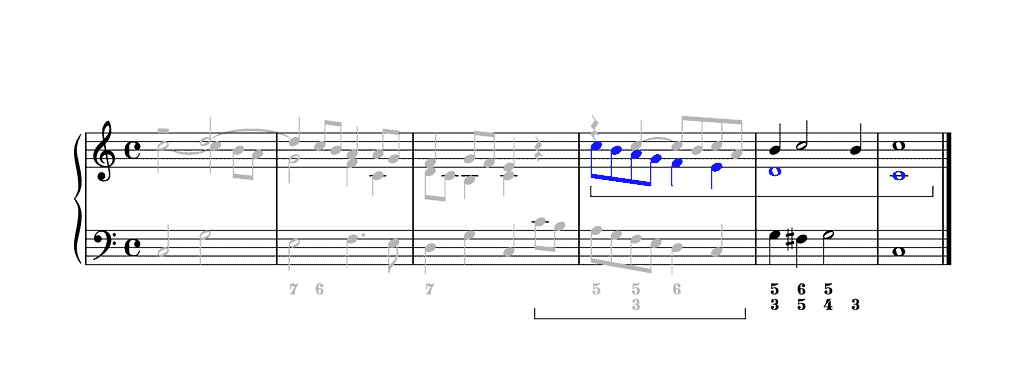

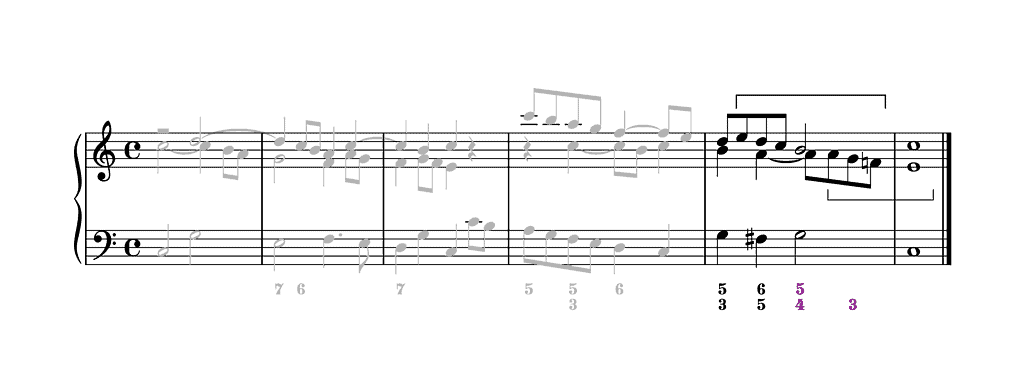

As I point out in my essay The 100 Versets by Stanislao Mattei, invertible counterpoint is an important technique in this style and in these versets. A student should therefore investigate if the upper voices can be swapped. While this is indeed often possible, sometimes the original voice leading is better than the swapped combination. Consider the next example, in which the upper voices are swapped:

The swap implies that the leading note stepping down now appears in the top voice, making this setting perhaps slightly weaker, though still usable, than if this snippet appeared in the middle voice.

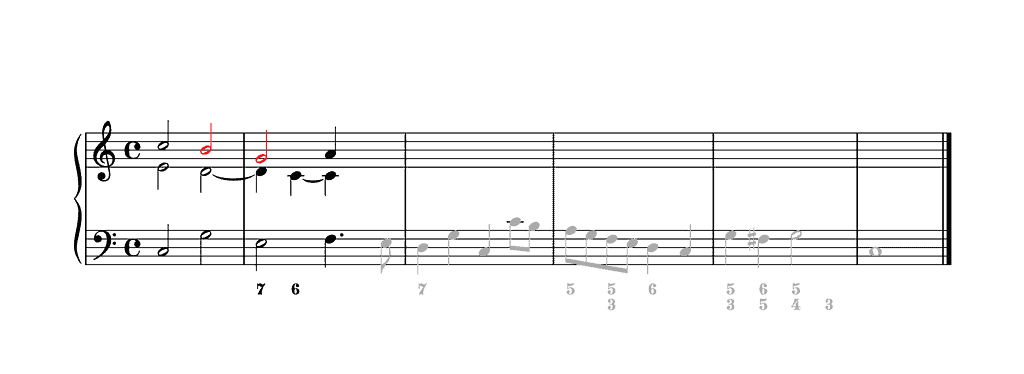

If we omit the passing note a1 altogether, the voice leading becomes unacceptable:

Until now, each bass note has been set with a single chord factor, embellished or not, in each part. Another solution to the ‘leading-note issue’ of bar 1b–2a is to double the bass note g (here in the middle voice) and put the third (b1) on beat 3 of bar 1 (in the upper voice).

On beat 4 of bar 1, the third leaps up to the fifth (d2), which prepares the seventh on beat 1 of bar 2, while the doubled bass note is held, resulting in an open fifth. If the tempo isn’t too slow, it shouldn’t be a problem that beat 4 of bar 1 doesn’t include the third. After all, the chord has been introduced on beat 3 including the third. Notice how the leaping third is used as a recurring motive in this setting, appearing in an ascending and a descending version. The next setting is a small variant of the previous one. The middle voice doesn’t begin with the other voices but enters on beat 2. As a result, the imitation between the two upper voices is clearer and each beat of bar 1 is marked.

The version above can easily be transformed into one in which each leap of a third is filled in with a passing note:

Notice that in this case the half note g in the bass in bar 1b has been transformed in a dotted quarter note g followed by an eighth note f. As such, a rhythmically stretched version of the main motive appears in bar 1b–2a. This rhythmically stretched version anticipates the one appearing in bar 2b–3a one tone lower.

To conclude the discussion of the first phrase, I will show one more setting. (There are obviously many more.) The setting below contains one good and one not so good idea.

Let’s start with the good idea. As in the previous setting, the three voices don’t start together. In this case, however, the middle voice starts with the bass, producing a vertical third. As for the upper voice, it enters on beat 2 doubling the bass. What isn’t good in this version is the fact that the middle voice first goes to d1 on beat 3 of bar 1 before leaping up to g1 on beat 4 simultaneously with the leap in the upper voice, a voice leading that overemphasizes the open fifth.

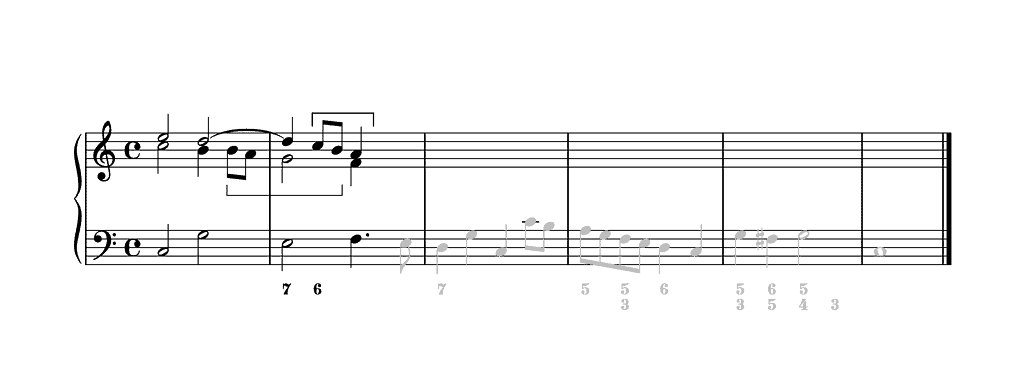

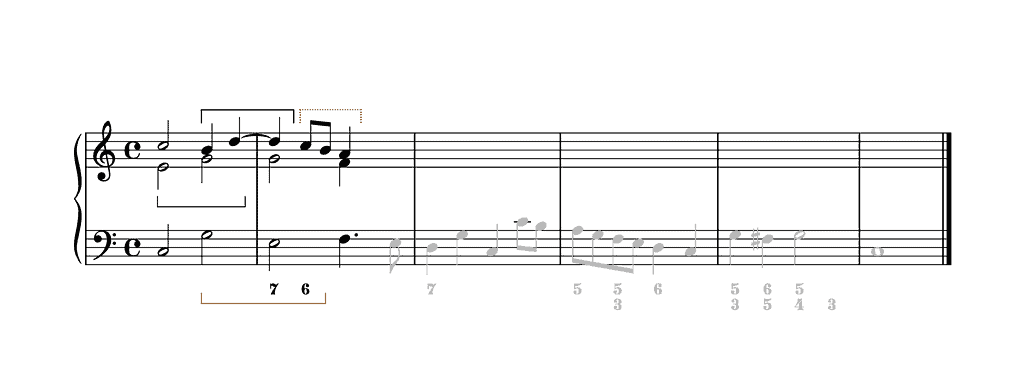

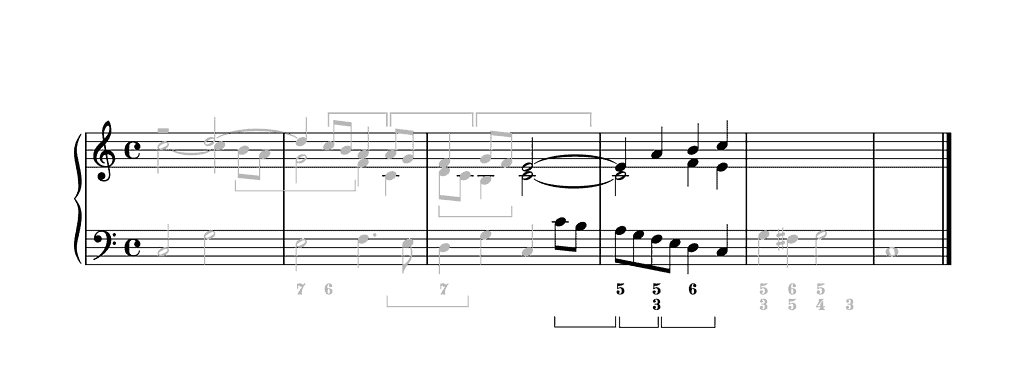

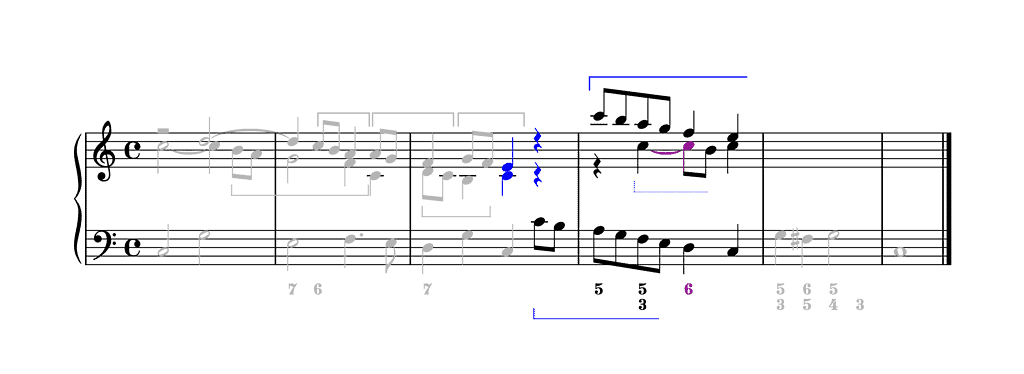

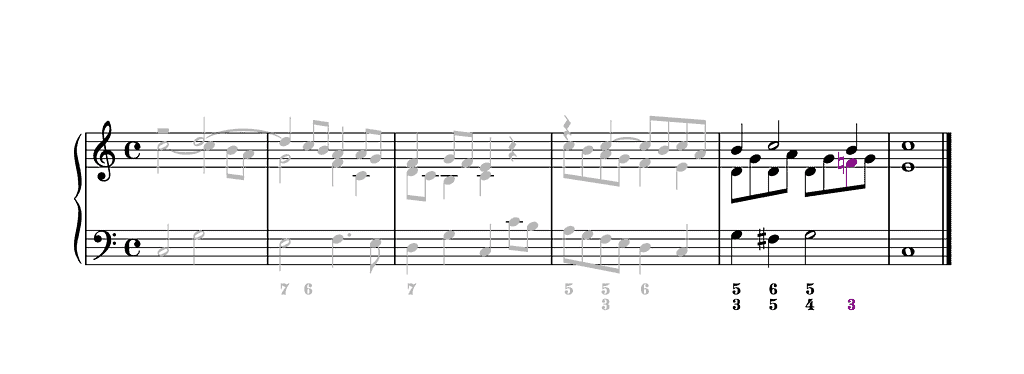

The second fragment of this verset has a typical melodic progression in the bass: ④–③–②–⑤–①. A standard way of setting this standard bass can be seen here:

Robert Gjerdingen has christened this pattern a Prinner. (For more information on this voice-leading pattern see my series on the Prinner.) One voice, in this case the middle voice, produces a descending melodic progression ➏–➎–➍–➌, which is a progression in parallel thirds with the bass. (Note that the g in the bass between d and c is optional and an afterthought of Mattei; the 1788 autograph has a half note d in the bass in bar 3a.) Another voice, in this case the top voice, stays as long as possible on ➊ until it becomes a dissonant —a seventh— on ②. That seventh then resolves by descending to ➐ on ⑤, after which ➐ rises to ➊ on ①. This idea of a prepared dissonance is taken over by the middle voice in bar 3. (Strictly speaking, the second beat of bar 3 hasn’t been figured with a “7”, as is the case for the first beat. Still, this voice leading is obvious. The fact that the “7” is lacking might actually be an oversight. The half note d in bar 3a of the autograph version of bar 3a is figured “7 6”, the “6” also implying an f in an upper voice.)

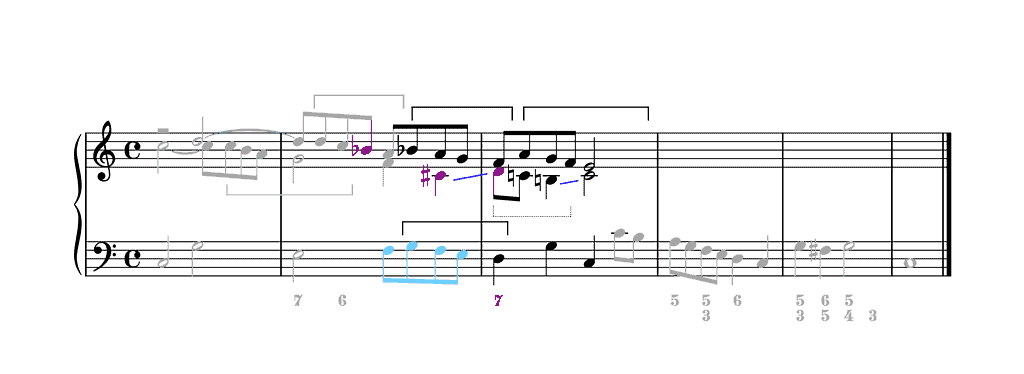

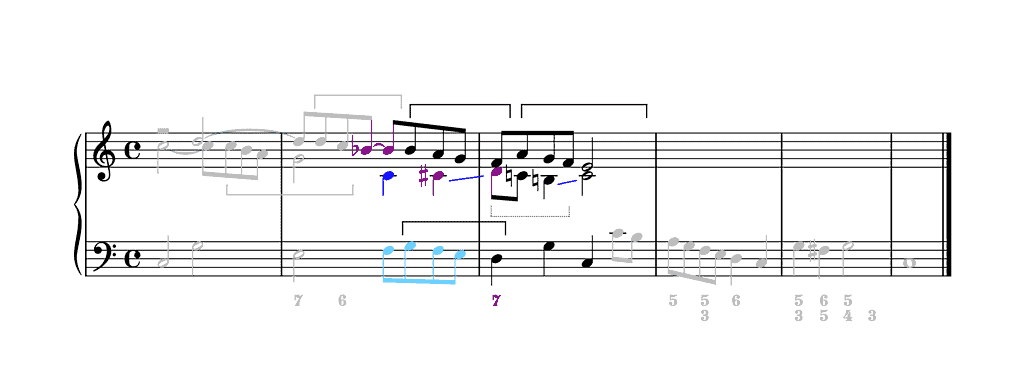

The second version of this phrase intensifies the use of the motive consisting of a stepwise descent spanning a third:

In this version, the original bass is slightly embellished in bar 2b, with the dotted quarter note f changed into a quarter note f followed by an eighth note f. And the half note f in the middle voice of bar 3a has been changed into a quarter note f followed by two eighth notes g and f.

Yet another motive consisting of a stepwise descent spanning a third can be added to this setting:

Instead of interpreting the figure “7” literally, i.e. as a suspension, I have delayed it an eighth note so that it becomes a passing note instead, being preceded by the doubling of the bass on the downbeat. As such, a rich imitative setting emerges.

Until now, the complete length of the dotted quarter note f in the bass in bar 2b has been interpreted as a F major chord. However, since the next note is an e, which is obviously a step lower than the f, one could interpret the moment of the dot as a suspension:

In other words, the top voices on beats 3 and 4 of bar 2 are set as if the bass has two quarter notes f–e.

In the following version, the dot is also treated as a dissonance, yet not as a suspension but as the bass note of a +4/2 chord:

Note that

- modern theorists would probably call this +4/2 chord a third-inversion dominant seventh chord.

- the historical name for a mild ④–③ cadence is a clausula altizans.

Another, consonant way to change the sonority on the moment of the dot is to change the triad into a sixth chord, an option that comes from the alternative setting of a descending scale in which every scale step, apart from both tonics, is set as a sixth chord.

Since the preparation of the seventh takes only an eighth note, the rhythmic value of the seventh in the upper voice on the downbeat of bar 3 can also be only an eighth note. Still, to allow the seventh to be present during the entire first beat of bar 3, one can simply repeat the c2 on the second eighth note of beat 1, a rhythmic motive that is imitated in the middle voice one beat later.

Note that the upper voices during the second fragment in the previous example cannot be swapped. The parallel fourths on beat 4 of bar 2 would become parallel fifths, the reason why parallel sixth chords only work with the sixths in the upper voice and the third in the middle voice. In contrast, the top voices of a standardized Prinner are written in invertible counterpoint, as illustrated in the following example:

(Apart from the version with parallel sixth chords on beat 4 of bar 2, the other versions we saw above also work if the top voices are swapped.) As we saw two examples ago, if one wants running eighth notes, one can easily achieve this by transforming the quarter-note suspension in the middle and top voices in the example above into an eighth-note suspension followed by its repetition as second eighth note:

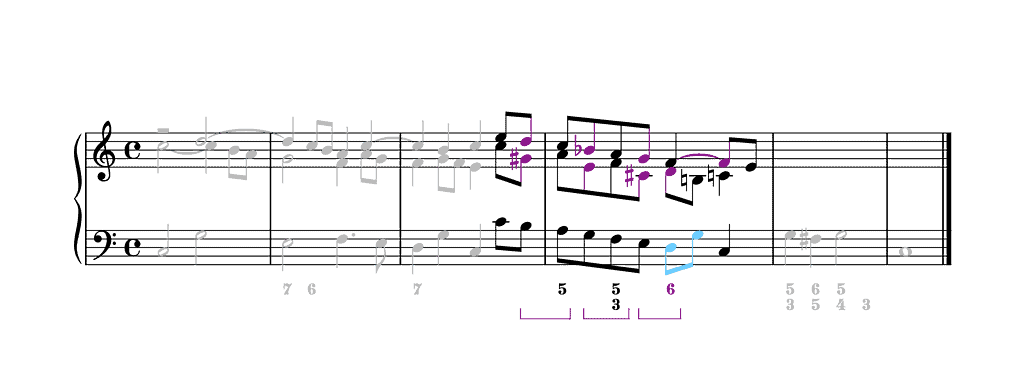

We saw earlier how the fact of delaying the “7” on the downbeat of bar 3 by an eighth note results in a D minor triad (without fifth). The presence of this minor triad gives the possibility to briefly focus on the key of D minor by introducing a C♯ during beat 4 of bar 2, a possibility illustrated by the next versions.

Here, the last eighth note in the middle voice in bar 2 is a c♯1, which is followed by a d1 on the next downbeat. The presence of this snippet above the e–d progression in the bass results in a temporary mild ②–① cadence (or clausula tenorizans) in D minor. C major is regained via the passing note c(♮)1 in the middle voice (the second eighth note of bar 3), which is followed by the transposition one tone down of the melodic progression ➐–➊, now in C major. (The transposed ➐–➊ snippet is part here of an imperfect ⑤–① cadence. In the 1788 autograph, however, it results in a second clausula tenorizans.)

(Some might interpret the succession of a D minor and a C major snippet here as the essence of a Fonte, in this case embedded in a Prinner. While this does indeed make sense in terms of voice leading, this succession does not fulfil the usual structural function of a Fonte. For more information on the Fonte see my series on this schema (The Fonte: The Basics, Extending the Fonte and The Fonte in Other Keys.)

Note how the top voice on beat 2 of bar 2 gives a b♭1 instead of a b(♮)1 as a passing note, resulting in a temporary mild ⑦–① cadence (or clausula cantizans or, as Gjerdingen calls it, Comma) in F major. This glance at F major is a good choice in function of the subsequent glance at D minor. The presence of this b♭1 makes the temporary focus on D minor smoother by first introducing the chromatically flattened note B♭ that is common to both keys, and then the chromatically raised note C♯ that establishes of D minor.

Note also what the inner voice produces in bar 2. Instead of giving an f1 or a c1 on beat 3, it prolongs the g1 by an eighth note, resulting in a 9–8 suspension that is not specified in the figures.

We saw above how the dot after the f in the bass in bar 2b can be interpreted as a suspension. Let’s look at a few more such settings, now with a brief shift to D minor at that spot.

Instead of producing two eighth notes c1–c♯1 on beat 4 of bar 2, the middle voice produces here a quarter note c♯1, resulting in two expressive intervals: a melodic diminished fourth f1– c♯1 and a vertical augmented fifth c♯1/f with the bass.

This version can easily be transformed into a setting with running eighth notes by continuing the suspirans motives of the first phrase:

Apart from the addition of the 4–3 suspension in the top voice in bar 2 that is not specified in the figures, the next version hardly differs from the previous one. Nevertheless, it contains an important voice-leading option:

Note how the middle voice in bar 2 leaps a fifth down from g1 to c1. This voice leading is

- common in the middle voice if

- the bass rises stepwise

- the first bass note is set as a sixth chord

- the second bass note is set as a triad or a diminished triad

- indispensable in a three-part texture if, in addition to the above conditions, a 4–3 suspension occurs in the top voice; after all, the second note of the melodically descending fifth is the fifth of the triad and makes the fourth really vibrate as a dissonance.

In the next version, a change of position of the F major chord occurs on beat 4 of bar 2, which produces a contrary motion between the outer voices:

As we saw higher, the C♯ can already appear precisely on beat 4 of bar 2. In relation to the voice leading of the example above, however, this requires the b♭1 to be chromatically raised to avoid a melodic augmented second:

In the example above, the b(♮)1 and g1 in the top and middle voice, respectively, on the second eighth note of beat 3 of bar 2 each work as a passing note. As we saw higher, if one places those two notes on beat 4, one obtains a +4/2 chord:

Note how this +4/2 chord on f doesn’t go to a minor sixth chord on e (a ‘C major sixth chord’), which would have resulted in a mild ④–③ cadence (or clausula altizans) in C major. (As a matter of fact, we saw this version above.) Instead, this +4/2 chord goes to a major sixth chord on e (with c♯2), which is the first sonority of a mild ②–① cadence (or clausula tenorizans) in D minor, as already pointed out.

Let’s move on the third fragment of this versetto, which is set as descending scale from c1 to c. Such a scale offers a multitude of realizations, some of which I will discuss here.

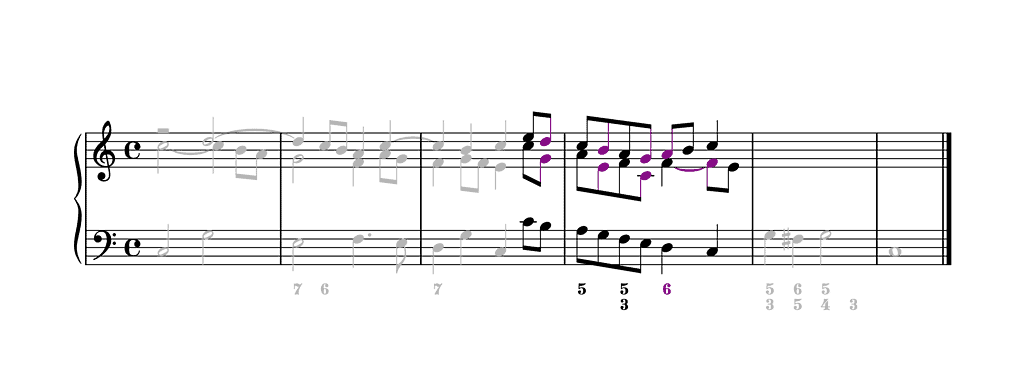

When we consider the second, fourth and sixth eighth notes of the descending scale as passing notes, this scale represents what Gjerdingen has called the Falling Thirds schema. The rudimentary realization of this schema is by setting each structural bass note as a triad. The following example shows such a realization, confirmed by the thoroughbass figures, with an upper voice moving in contrary motion:

(A famous example of this pattern is the opening of the Air from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Third Orchestral Overture in D major BWV1068. Note that this air is often —and incorrectly— called “Air on the G string”, when in fact the latter is an 1871 arrangement by the German violist and pedagogue August Wilhelmj (1845–1908). Wilhelmj transposed the piece to C major and wrote the solo/first violin part an octave lower so that the entire part could —and should— be played on the violin’s lowest string, the G string, as indicated in the score (auf der G-Saite).)

A scalar passage always offers several possibilities for imitation at the octave. In the following example, the upper voice imitates the a–g–f(–e) bass motive:

Notice how this type of imitation is characterized by parallel thirds.

In the next version, there is a voice swap on the second structural note of the Falling Thirds schema, on the a on the downbeat of bar 4. As a result, the voice that imitates the bass motive is the middle voice:

Note first that in the bass in bar 3b of the next example, I have changed the quarter note c and eighth note c1 into a dotted quarter note c. As such, this example allows two levels of imitation. First, the middle voice imitates the b–a–g–f(–e) bass motive. Secondly, the middle voice imitates the c–b–a–g–f(–e) bass motive.

Note that the first note of the second level of imitation is not literal; the middle voice starts its imitation with a e1 instead of a c1.

In the next example, the middle voice starts in parallel thirds with the bass for the three notes, the last of which becomes a stationary note until it turns into a dissonant seventh on beat 3 of bar 4. This motive consisting of a stepwise descent spanning a third is imitated by the upper voice.

Note how

- beat 4 of bar 3 doesn’t represent a C major triad but that the 7–6 suspension of beat 3 is repeated one tone lower

- the last eighth note in the middle voice of bar 4 —a1— ensures a strong drive towards the final cadence of this versetto.

I have saved the most accomplished imitative settings for last. In the following version, the bass starts alone on beat 4 of bar 3. One beat later, the middle voice imitates the bass. Again one bar later, the upper voice joins in on the same note.

Note, however, that the imitation in the upper voice needs to break off already from the second note; there would be unacceptable parallel fifths with the bass otherwise:

And this is the same imitative setting with the upper voices swapped:

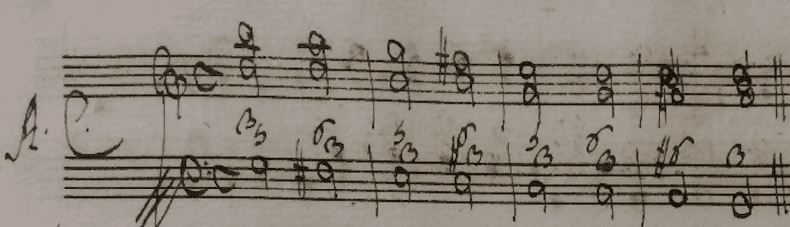

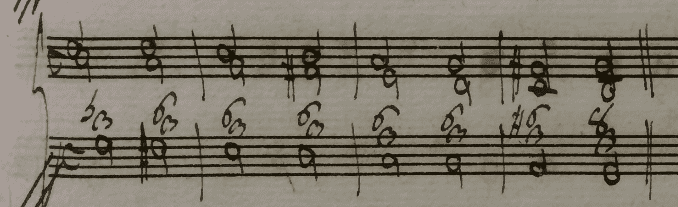

Let’s explore some settings now where each note of the descending octave supports an individual chord/sonority. As an alternative setting for the rule of the octave, one can alternate triads and sixth chords, a setting that Gjerdingen has called a Stepwise Romanesca. Below you see this voice-leading pattern in G major in a version with parallel thirds between the outer voices from a manuscript I have discovered in the Archivio Musicale della Biblioteca San Francesco in Bologna, Italy:

(This manuscript consists of the first three books of rules and partimenti by Fedele Fenaroli. For more information on Fenaroli’s curriculum and more specifically on this manuscript see my article On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update and the preface of my critical edition of Fenaroli’s first three books.)

When we apply this voice leading to the third fragment from Mattei’s first versetto in C major, this is the result:

An important difference with Fenaroli’s example, of course, is the harmonic rhythm. While both examples are written in C (or 4/4), the harmonic rhythm in Fenaroli’s illustration is slow —harmony changes every half note instead of every quarter note— while that in the example above is fast —harmony changes every eighth note. The reason I mention this is that there is a possible issue of hearing parallel fifths between middle voice and bass in the example above. After all, those fifths fall on successive beats, not successive half notes. Whether or not this voice leading is acceptable thus depends on the tempo. If the tempo is (too) fast, these fifths will sound too prominent because the second eighth note of every beat in the outer voices will sound more as passing notes than constituting sixth chords.

If you want to avoid this possible perception of parallel fifths in any case, the following voice leading is without problem:

Thanks to the doubling of the bass note on the beats and the descending melodic leaps of a fourth towards the second eighth note of every beat, one clearly perceives a harmonic rhythm per eighth note, eliminating every possible problem of faulty parallelism. In other words, while the interval between the middle voice and the bass on every successive beat is an octave, possible parallel octaves are eliminated thanks to the clearly perceivable sixth chords in between them.

While the outer voices move in parallel thirds for the full extent of the descending octave in the previous version, the upper voice can also conclude in contrary motion:

In this case, the ② (here d) of the mild ②–① cadence (or clausula tenorizans) is set successively with a fifth (➏, here a1) and a sixth (➐, here b1) in the top voice, a voice leading that enables to finish in a higher position.

Fenaroli also proposes a more straightforward way of setting each note of a descending scale with an individual chord/sonority:

In this case, every scale step, apart from both tonics, is set as a sixth chord. The following example illustrates this setting during the third fragment of Mattei’s first versetto in C major:

All the settings of the descending scales seen until now firmly remained within the key of that scale, C major. There are a number of settings, however, that enable focusing on other keys as well. Consider the next setting.

In this case, every even eighth note and the following uneven eighth note are interpreted as a local ②–① cadence (or clausula tenorizans). This implies that the following keys follow each other in this fragment: C major, A minor, F major, D minor and again C major. Note that I have modified the bass on beat 3 of bar 4, replacing the ②–① cadence (or clausula tenorizans) in the home key with an imperfect ②—⑤–① cadence. The reason for this is to avoid a possible perception of parallel octaves between the inner voice and the bass between beats 3 and 4 of bar 4. The octaves on the beginning of those beats are still there, of course, but the fact that both voices move to a different interval, thereby clearly creating a new chord, eliminates this potential voice-leading error.

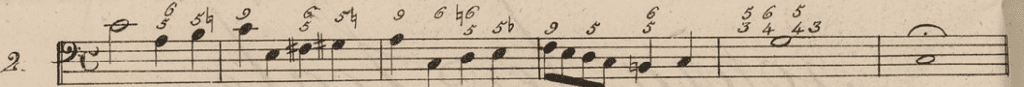

Note that this version comes close to what Vasili Byros has labelled a Fonte-Romanesca, “as it results from a combination of features belonging to the Romanesca and the Fonte” (Byros (2017), p. 77). What the Fonte-Romanesca has in common with the Romanesca is that each subsequent segment is a third lower. (Note that this type of sequence is rather exceptional. Indeed, most moti del basso are progressions in which each subsequent segment is a second lower or higher.) What the Fonte-Romanesca has in common with the Fonte is that each segment is a mild ⑦–① cadence or clausula cantizans (or, as Gjerdingen calls it, Comma). Typical of the Fonte-Romanesca, however, is that each of these cadences is usually extended into a ⑥–⑦–① snippet, which Gjerdingen calls a Long Comma. Mattei himself made his students practice this very voice-leading, with which the second versetto in C major, amongst others, begins:

The next two settings each focus on (only) one extra key apart from the home key. In the example below, the first five notes of the descending scale are interpreted as ⑤–④–③–②–① in F major. In this case, b in the bass has been modified into b♭.

Note

- that the 6/4 chord/sonority on the downbeat of bar 4 (on the local ③ in F major) is a by-product of the counterpoint

- the contrary motion between the outer voices

- the mild ②–① cadence (or clausula tenorizans) in bar 4b, set successively with a fifth (➏, here a1) and a sixth (➐, here b1) in the top voice.

In the next example, almost the entire scale is interpreted as belonging to D minor. Also in this case, b in the bass has been modified into b♭.

Note again the 6/4 chord/sonority on the local ③ (the f in D minor on beat 2 of bar 4) and the contrary motion between the outer voices.

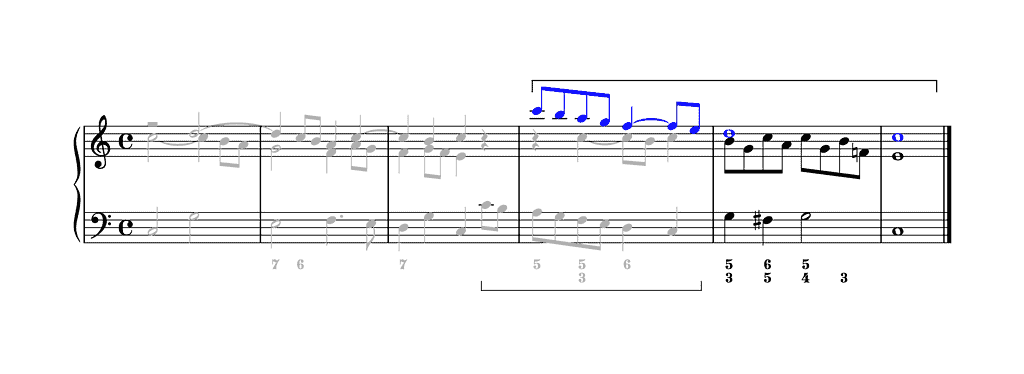

Let’s move on to the last fragment, which is a modified cadenza doppia. (For more information on the cadences and more specifically on the cadenza doppia see my essay Cadences: The Basics.) The next example shows the straightforward way of setting the last two bars, which includes the conclusion of the entire descending scale imitated by the inner voice.

Notice

- how notes 5 and 6 of the scale in the middle voice are doubled in length compared to those in the bass

- how notes 7 and 8 of the scale in the middle voice are quadrupled in length compared to those in the bass

- the presence of the incomplete neighbour note a1 as the last eighth note in the top voice.

A downside of the version above is the loss of rhythmic eighth-note drive one bar before the final bar. This can be easily fixed using a technique that is called compound melody. “In compound melody two or more voices in a progression are transformed into a single melodic part, with that part leaping between the factors in the chord progression. Compound melody differs from arpeggiation in that the leap can take place across a harmonic boundary” (Schubert & Neidhöfer (2006), p. 45). Consider the middle voice in the example below.

Play this bar first as written. Now play each even eighth note of the middle voice simultaneously with the previous uneven eighth note. The result of this is that you get a four-part instead of three-part texture. Now play the cadence as written again to fully appreciate the technique of compound melody.

In the next setting, the imitation of the entire descending scale appears in the upper voice while the inner voice produces a different kind of compound melody:

The next setting starts with compound melody, after which the writing becomes imitative:

As the thoroughbass figures of beat 2 of bar 5 indicate, a 6/5 chord is wanted here. While one can play the sixth and the diminished fifth simultaneously in two different voices, as indeed suggested by the thoroughbass figures, it is also possible to horizontalize this dissonance. In this case, the sixth and the diminished fifth are played successively in one voice. It is more usual to start with the sixth, resulting in a consonant sixth chord. If the diminished fifth follows the sixth, it normally works as a passing note. In the example below, however, the diminished fifth works as the preparation for the vertical fourth on ⑤.

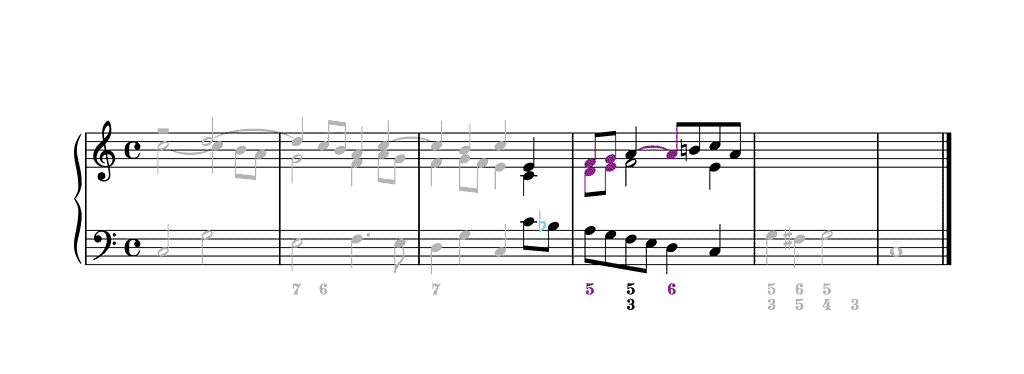

In the last example, a suspirans is used imitatively. It occurs first in the top voice and half a bar later in the middle voice.

Note

- how the thoroughbass figures on beat 3 are ignored; no 4 but 3 is played, resulting from the presence of the suspirans in the top voice

- the 9–8 suspension in the middle voice, which makes up for the absence of the 4–3 suspension.

Select Bibliography

Byros, Vasili. Mozart’s Vintage Corelli: The Microstory of a Fonte-Romanesca, in: Intégral 31 (2017), 63–89.

Demeyere, Ewald. Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue — Performance Practice Based on German Eighteenth-Century Theory (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2013).

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207–229.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Kirnberger, Johann Philipp. Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik (Berlin and Königsberg, 1771/1774 (vol. 1). English translation in: The Art of Strict Musical Composition – Johann Philipp Kirnberger, ed. David Beach and Jurgen Thym (New Heaven and London: Yale University Press, 1982).

Schubert, Peter & Christoph Neidhöfer. Baroque Counterpoint (New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006).