This essay is the fourth and last of a series devoted to changing-note schemata, a type of dichotomous schema with a treble and/or a bass whose melodic shape look like a gruppetto or a musical turn (~). In this essay, I will discuss the schema that Robert O. Gjerdingen has labelled the Jupiter.

A Jupiter is mostly a dichotomous schema that features a ➊–➋…➍–➌ treble line and can be set with several counterpoints in the bass.

(Admittedly, the shape of the Jupiter’s treble and bass lines does not, strictly speaking, resemble a musical turn. However, since Gjerdingen includes it in his chapter on the Meyer, the Aprile and the Pastorella, I have decided to include in the series of changing-note schemata.)

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in an upper part (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Note further that ‘Bar 1a’ refers to the first half of bar 1, ‘bar 1b’ to its second half.

Term and Interpretation of the Jupiter

The term and interpretation of the Jupiter come from Robert O. Gjerdingen. He defines a Jupiter as a proposta schema that comprises two dyads, as does the Meyer, the Aprile and the Pastorella. (In one variant, featuring a ③–④–⑤–… bass line, the construction with two perceivable dyads is absent.) In fact, the Jupiter, the Pastorella and the Meyer share the second dyad with a ➍–➌ treble line. And the treble lines of the Jupiter and the Meyer are nearly identical, differing only in the second note: ➋ in a Jupiter, ➐ in a Meyer. Similarly closely related are the Jupiter and the Paired Do–Re–Mi, differing only in the third note: ➍ in a Jupiter, ➋ in a Paired Do–Re–Mi.

Like the Meyer, the Aprile and the Pastorella, the ➌–➋…➍–➌ treble line of the Jupiter can

- include onbeat dissonances during stages 2 and/or 4

- have several counterpoints in the bass.

The Jupiter with a ①–⑤…⑤–① Bass Line

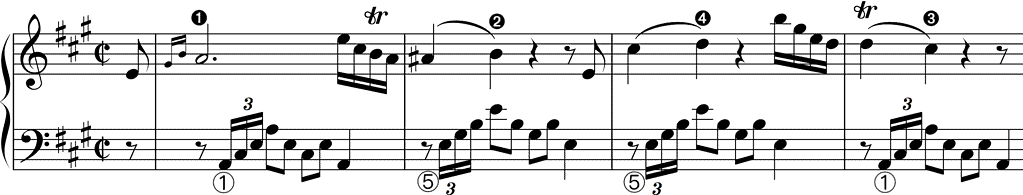

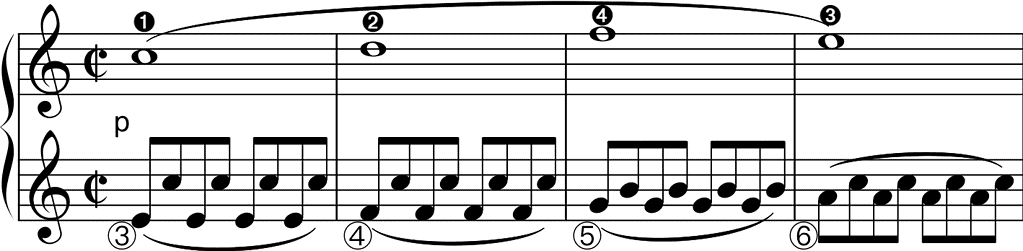

The treble line of a Jupiter can be accompanied with a ①–⑤…⑤–① bass line. Such a Jupiter appears as the opening theme of the first movement of the Sonata for the Harpsichord, Which can be Played with the Accompaniment of a Violin or Transverse Flute, and a Violoncello in A major KV 12 by the eighth-year-old Mozart, published in London in January 1765:

Note

- the chromatically ascending appoggiatura in the treble line during stage 2 (bar 2a)

- the diatonically ascending appoggiatura in the treble line during stage 3 (bar 4a) (The presence of an appoggiatura in the treble during stage 3 of a dichotomous Jupiter —and more broadly of a dichotomous schema— is quite exceptional. In this case, it may be attributed to the fact that it was composed by a brilliant eight-year-old prodigy who, nonetheless, still had a thing or two to learn.)

- the High ➋ Drop during stage 3 (bar 3b)

- the diatonically descending suspension in the treble line during stage 4 (bar 4a).

The Jupiter with a ①–④–⑤–① Bass Line

Stage 2 of a Jupiter can also feature ④ in the bass line, transforming the Jupiter from a dichotomous schema into a single-gesture schema.

Haydn uses a straightforward example of a Jupiter with a ①–④–⑤–① bass line to open the minuet of his String Quartet in G major op. 76 No. 1:

bars 1–4, Leipzig: Ernst Eulenburg, ca. 1930–1935, public domain, available on https://imslp.org

(Ernesto Hartmann refers to a ①–④–⑤–① bass line as a Bergamasca. See, amongst other, this YouTube video and its accompanying text.)

Regarding the first violin, note

- the anticipations as upbeats to bars 2 and 3

- the unprepared seventh at the start of stage 3 (By Haydn’s and Mozart’s time, the fact that the seventh of the dominant seventh chord was neither prepared nor functioned as a substitute for the fifth was no longer a concern. Fedele Fenaroli (1730–1818), for instance, wrote that “La settima minore, e la quinta falsa, sono consonanze; perchè non hanno bisogno di preparazione, ma soltanto di risoluzione calando di grado” (The minor seventh and diminished fifth are consonants since they require no preparation but only resolution via a descending second). Fenaroli, 1795: 6, footnote 1. For more information see Demeyere, 2018 and Demeyere, 2021/2023.)

- ♯➋ as the chromatically raised fifth on ⑤ (beat 3 of bar 3), a typically galant chromatic alteration. (In his monumental Music in European Capitals: The Galant Style, 1720–1780, Daniel Heartz provides a wealth of examples of this type of alteration, the first of which are discussed on pages 265–266.)

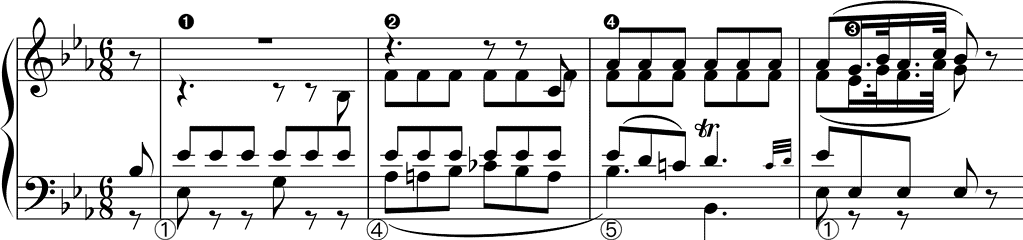

A more intricate example of this schema opens the Andante from Mozart’s 40th Symphony:

Note

- how the treble line of the Jupiter begins in the viola (stage 1, bar 1), continues in the second violin (stage 2, bar 2) and concludes in the first violin (stages 3 and 4, bars 3 and 4)

- that an appoggiatura occurs at the start of the Jupiter’s third stage, though not in the treble line of the Jupiter but in a middle part, as this Jupiter is not structured dichotomously.

The Jupiter with a ③–④–⑤–① Bass Line

Instead of beginning with ① in the bass, it can also start with ③, resulting in a bass that is somewhat lighter and prominently stepwise:

Note

- how, despite two octave leaps and one leap of a tenth, the essentially stepwise motion of the Jupiter’s treble remains intact (as can be seen in the middle of both bars)

- the chromatically ascending appoggiatura in the treble line during stage 2 (bar 2a) (This is the same appoggiatura that the young Mozart used in the Jupiter’s treble in bar 2 of KV 12/i. In contrast to that treble, however, Haydn did not include any additional appoggiaturas.)

The Jupiter with a ③–④–⑤–⑥ Bass Line

Rather than concluding with an imperfect clausula basizans or ⑤–① cadence, a Jupiter can also end with a deceptive ⑤–⑥ cadence, as Mozart does at the beginning of the fourth movement of his 41st symphony:

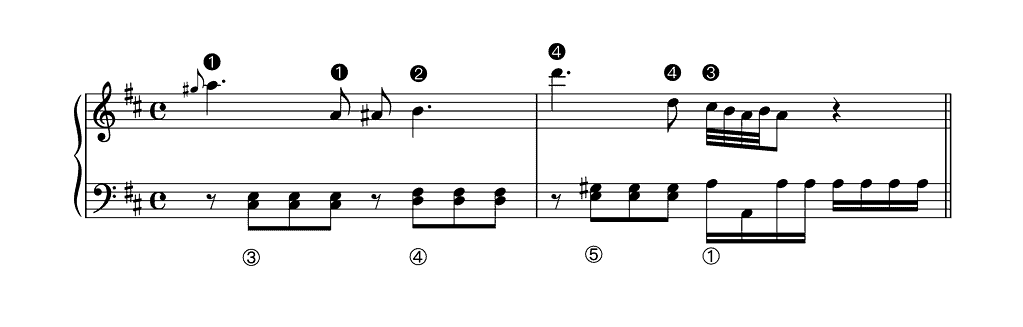

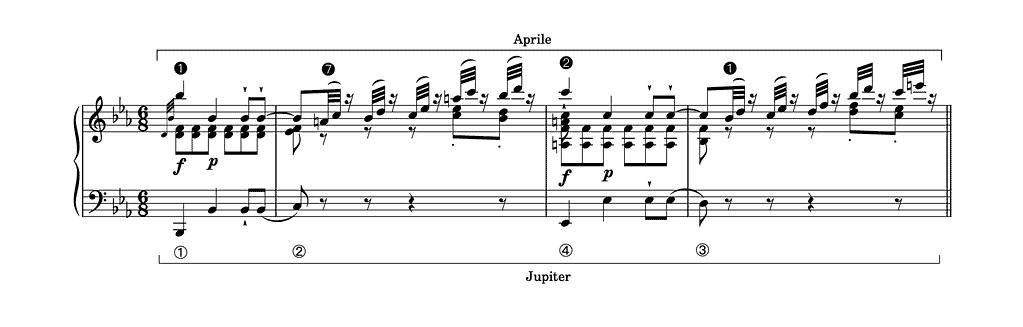

The Jupiter Treble Repurposed as the Bass Line of an Aprile

As I pointed out in my essay The Aprile, the Jupiter treble can serve as a bassline counterpoint to the Aprile treble, with the second dyad acting as a clausula altizans. Here is the example I presented in that article:

Note that stages 2 and 4 include a suspension in the upper part, resulting twice in a 7–6 suspension.

Further Reading (Selection)

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207–229.

Demeyere, Ewald. Metodo per bene accompagnare Del Sig:e Maestro Fedele Fenaroli, Critical Edition (Ottignies: https://essaysonmusic.com/resources/, 2021, revision of 3 February 2023).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER LI PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO. NUOVA EDIZIONE ACCRESCIUTA. [Third edition] (Naples: Domenico Sangiacomo, 1795).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Heartz, Daniel. Music in European Capitals: The Galant Style, 1720–1780 (New York: Norton & Company Ltd., 2003).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).