In this essay, I will discuss the characteristics of a voice-leading pattern known today as the Monte Romanesca, to which I have added the adjective ‘Leaping’ to distinguish it from the stepwise version, which is dealt with in a separate essay.

The term Leaping Monte Romanesca refers to a bass motion that rises a fifth and falls a fourth, regardless of the setting, or, more specifically, to that bass set with canonic imitation in the upper parts based on a line alternating rising fourths and falling steps, including 4–3 suspensions.

This essay addresses the following topics related to the Leaping Monte Romanesca:

- Term(s) and interpretation

- Mode and structure

- Length of the pattern

- Structural use

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the melody (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①).

Term and Interpretation

The term and interpretation of the Monte Romanesca comes from Robert O. Gjerdingen: “Because this pattern begins like a Romanesca but then rises where the Romanesca would fall, I term it a ‘Monte Romanesca’” (Gjerdingen (2007), p. 99). At the same time, Gjerdingen argues that the Monte Romanesca is sufficiently distinct from both schemata that “it could equally well be treated as a separate schema” (Gjerdingen (2007), p. 99). John A. Rice, author of the article Climbing Monte Romanesca: Eighteenth-Century Composers in Search of the Sublime from 2017, “would go a little further, saying explicitly that the Monte Romanesca is neither a Monte nor a Romanesca but a schema with its own long history” (Rice (2017), p. 2).

Note that

- Within partimento and counterpoint teaching, the Leaping Monte Romanesca also seems to have been considered a distinct musical phenomenon, as it was given a distinct label: “a bass motion that rises a fifth and falls a fourth”, or something along those lines. (A bass motion is defined by simply describing the first two intervals of the bass, the first interval indicating the interval of the model, the second the interval of the last note of the model and the first note of the first transposition. See also my essay Disjunct Moti del Basso).

- Modern theory calls this pattern a “rising-fifths sequence”.

Mode and Structure

A Leaping Monte Romanesca occurs only in major and can have two, two and a half or three segments. (There are examples of a Leaping Monte Romanesca with more than three segments, but they are exceptions and are beyond the scope of this essay.) Although schemata theory also defines a variant in which each segment is built on a descending step in the bass, this is historically another bass motion, labelled as a moto del basso, che scende di grado, e sale di terza (a bass motion that falls a step and rises a third).

The Bass of a Leaping Monte Romanesca

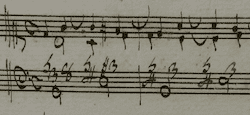

Below you can see the bass of a Leaping Monte Romanesca, which is characterized by a model consisting of a rising fifth transposed at least once a up step:

Note that the second structural note of each segment can also be a fourth below rather than a fifth above the first:

Realizing this Bass

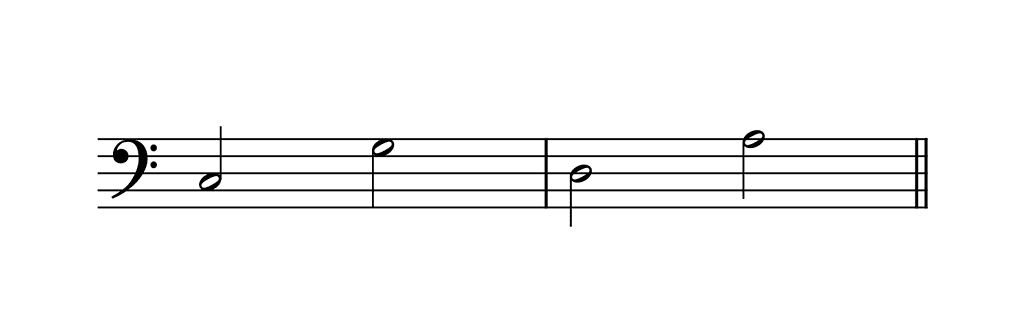

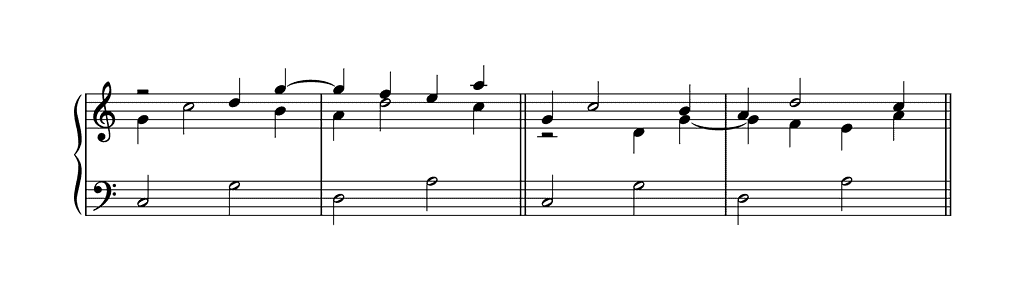

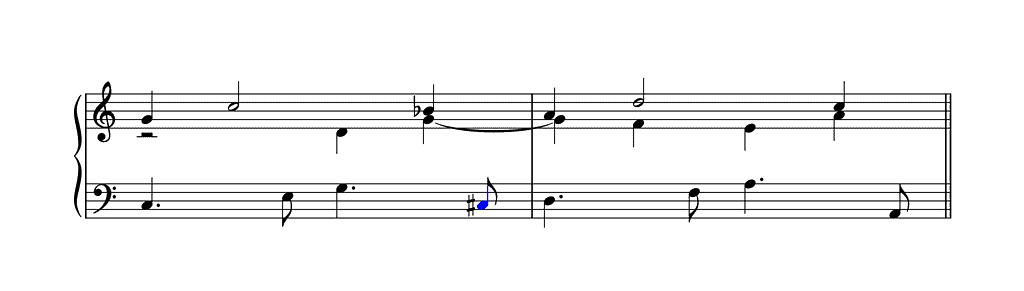

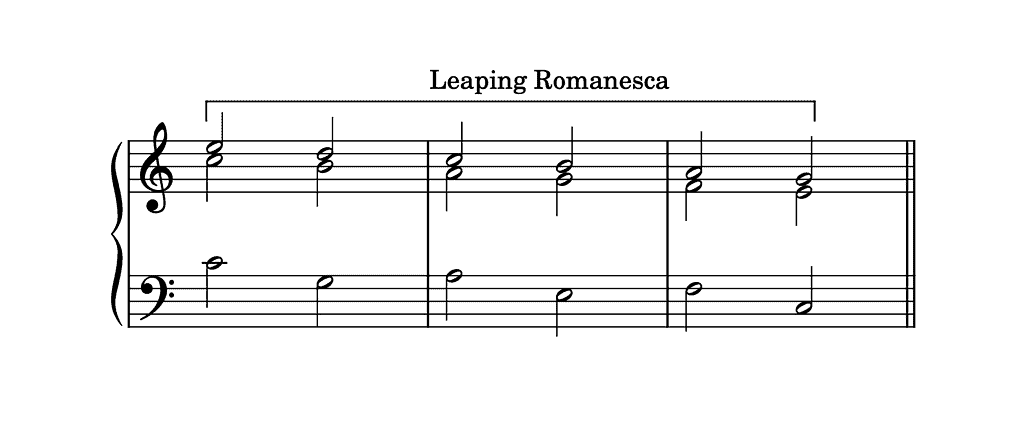

One of the features of 18th-century Neapolitan training in composition is that students needed to find as many settings as possible, each of which is described by mentioning only the bass motion. In the case of a bass that rises a fifth and falls a fourth, the first setting a student would learn is the one in which each stage is simply set with a triad:

Note that each bass note is alternatively set with an incomplete and a complete triad.

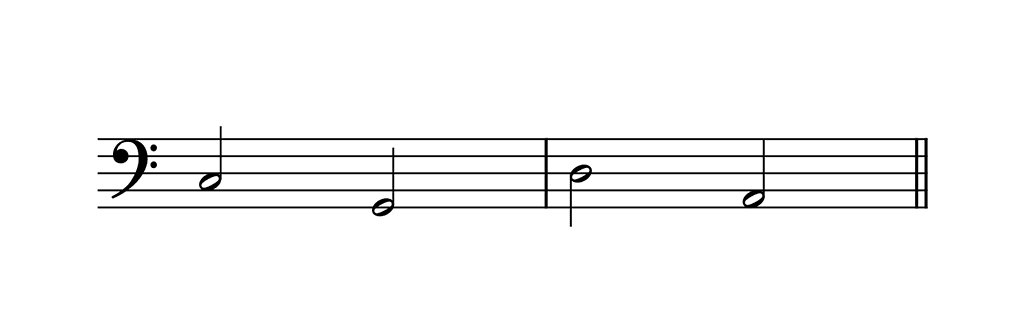

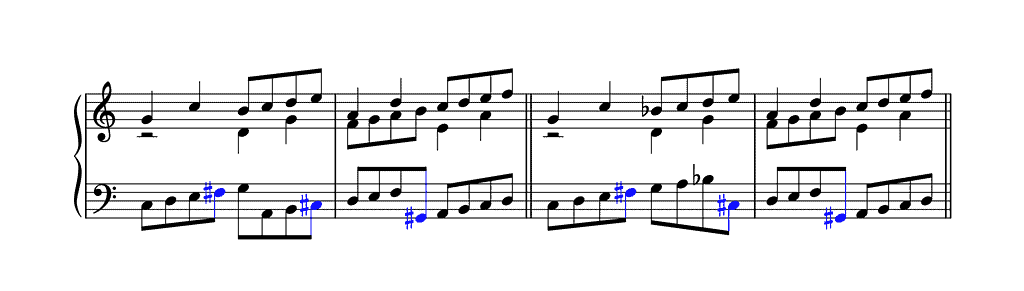

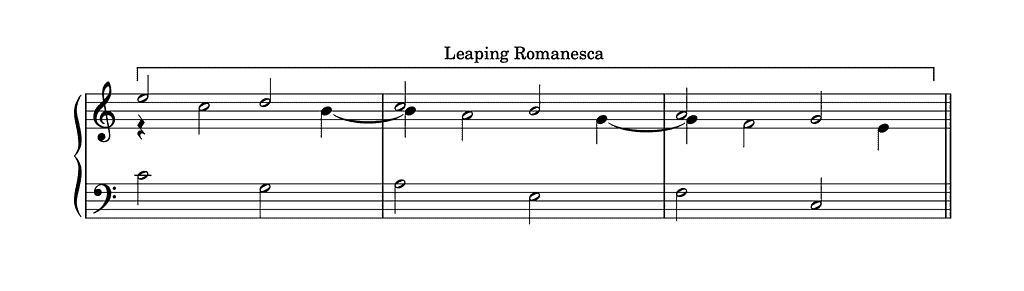

Yet certain settings of a bass have been used much more than others, both pedagogically and in compositions. In the case of a bass that rises a fifth and falls a fourth, the setting with canonic imitation in the upper parts based on a line alternating rising fourths and falling steps, including 4–3 suspensions, was very popular:

Notice how

- The second note of each rising fourth is tied, becoming a suspension.

- The suspension resolves stepwise after which the line descends another step, corresponding to the first note of the next rising fourth.

Reflections On Terminology

One might ask why Gjerdingen coined a new modern term —(Leaping) Monte Romanesca— for a pattern that already had a (historical) name —a bass motion that rises a fifth and falls a fourth. Don’t these two labels describe the same musical phenomenon? No, not always. The term ‘schema’ used today by schemata theorists is often not identical to what an 18th-century Italian musician understood by the term moto (or movimento) del basso, which is usually translated as bass motion. A schema is generally characterized not only by a specific bass line, but also by one or more standard upper parts. According to Gjerdingen, “Many galant schemata could be described as a pas de deux with the part of the danseuse usually given to the melody and that of the danseur to the bass” (Gjerdingen (2007), p. 65). As for a bass motion, it is literally what it says: a progression in the bass, whereby the upper part(s) are left unspecified. In other words, whatever the realization, the setting is always named after its bass.

Yet the term Monte Romanesca as used by Gjerdingen is less a fixed schema with a typical bass and upper voice(s) than others he has coined or discussed. In his book Music in the Galant Style, Gjerdingen uses the term (Leaping) Monte Romanesca in two ways:

- for any setting of a bass that rises a fifth and falls a fourth, making the label Monte Romanesca synonymous with the historical term (John Rice calls this a “Monte Romanesca as defined broadly”)

- for the specific setting with canonic imitation in the upper voices, making this label more in line with the concept of a schema (in Rice’s words, a “Monte Romanesca as defined narrowly”).

However, as Rice has pointed out, Gjerdingen more often speaks of a Monte Romanesca in a narrow sense than in a broad sense. Moreover, “Gjerdingen refers to several instances of the ‘up-a-fifth, down-a-fourth movimento’ in the bass without using the term ‘Monte Romanesca’, presumably because these lack 4–3 suspensions and the other features of the Monte Romanesca in the narrow sense” (Rice (2017), p. 4, footnote 7).

The Two-Part Leaping Monte Romanesca

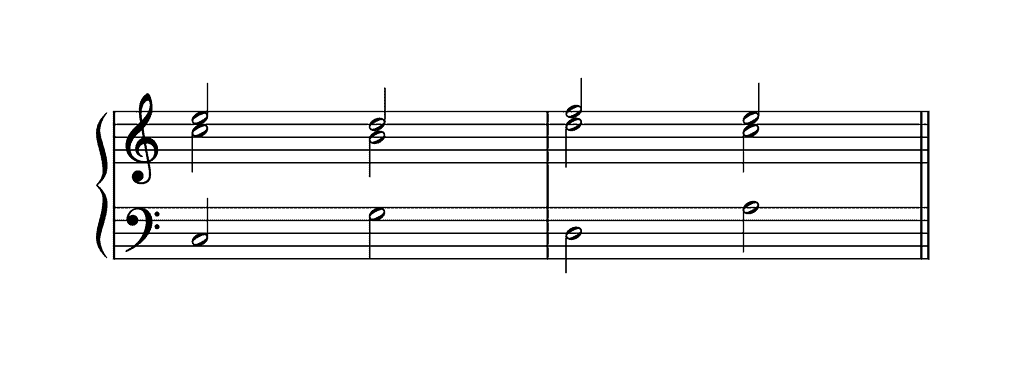

The shortest type of Leaping Monte Romanesca consists of two segments. The next example shows the two-part schema in its most basic version, in which each bass note is set as a triad:

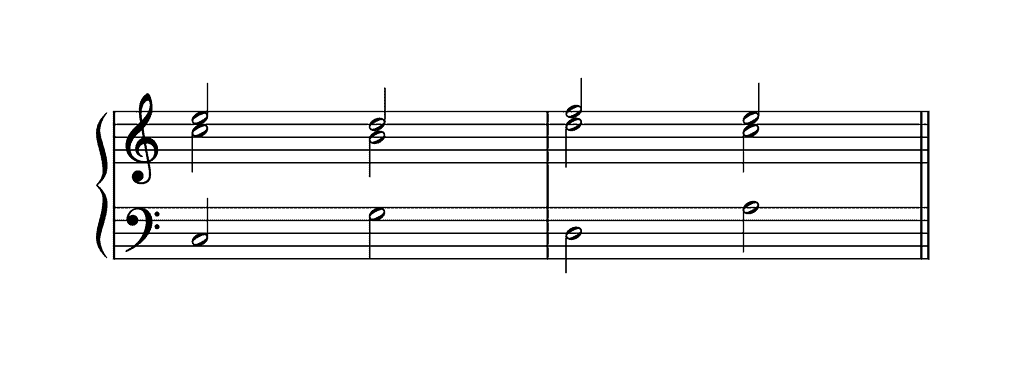

And here you see a two-part Leaping Monte Romanesca set with canonic imitation and 4–3 suspensions:

(These are the same examples as those under the section Realizing this Bass.)

The second bass note in these examples may also have a minor third, already announcing the minor quality of the second segment:

The Two-Part Leaping Monte Romanesca with Tonicization

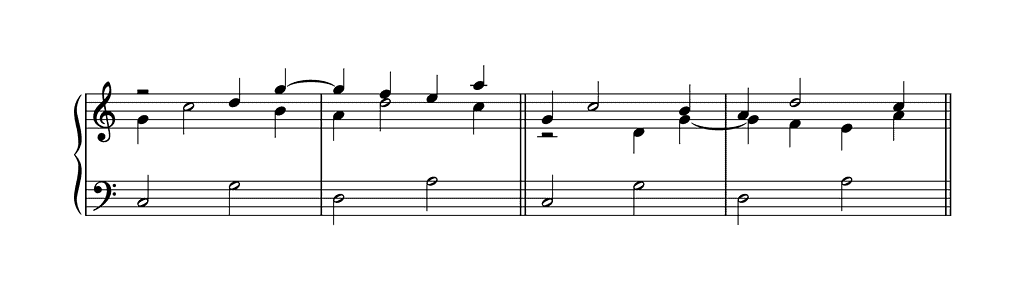

A Leaping Monte Romanesca can also contain local-key fragments, where tonicization can occur at the level of a segment or of a bass note. In the next example, D minor —the start of segment 2– is announced by the c♯ in the bass:

In the next example, stages 2 and 4 are also tonicized by introducing them in the bass with an eighth note f♯ and G♯, respectively:

Notice that

- the rising fourths are present, but the 4–3 suspensions are not to make the counterpoint smoother

- in the example on the left, the second structural note of the model is set with a major third and an octave displacement in the bass after the first eighth note

- in the example on the right, the second structural note of the model is set with a minor third and an octave displacement in the bass after the third eighth note, avoiding an ascending melodic augmented second

- in both examples, G♯ occurs instead of g♯ to avoid an ascending melodic augmented second in the bass of stage 3; as such, the second structural note of the second segment is a fourth below instead of a fifth above the first structural note.

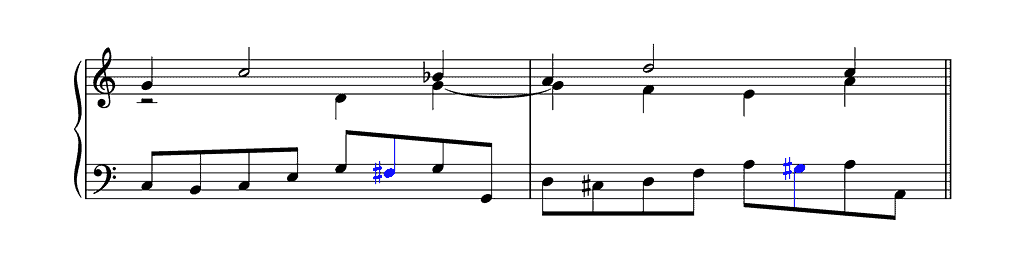

The (hint of) tonicization also works when those notes are introduced as lower neighbour notes:

Note that the octave on beat 2 of bars 1 and 2 is not direct because the preceding beats represent the same sonorities.

The Two-and-a-Half-Part Leaping Monte Romanesca

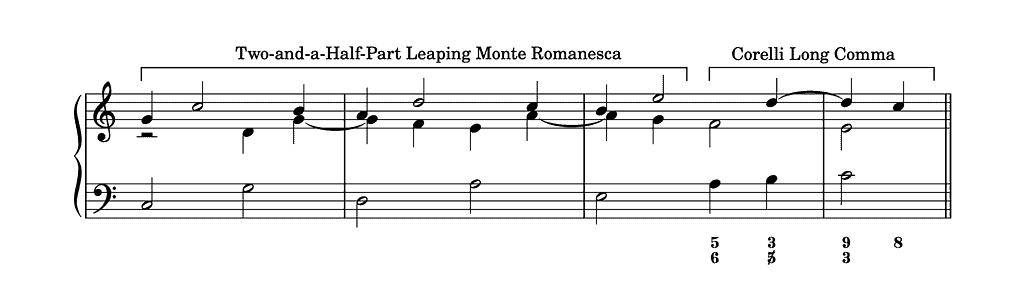

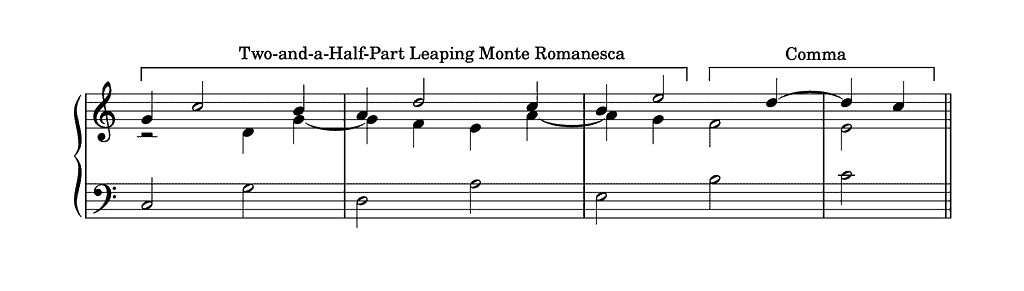

A Leaping Monte Romanesca can also consist of two and a half segments, with the third segment breaking off after its first structural note and often followed by what Rice calls a Corelli Long Comma, that is, a Long Comma with a 6/5 sonority above ⑥ and a 9–8 suspension above ①:

A two-and-a-half-part Leaping Monte Romanesca can also be followed by a (regular) Comma, which creates the illusion that this schema consists of three rather than two and a half segments due to the rising fifth in the bass of the third segment. Yet the second note of this rising fifth is not set with a perfect but with a diminished fifth, which initiates the Comma.

The Three-Part Leaping Monte Romanesca

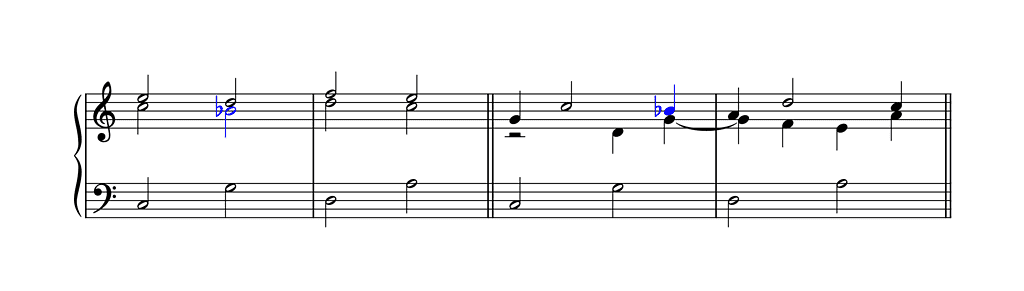

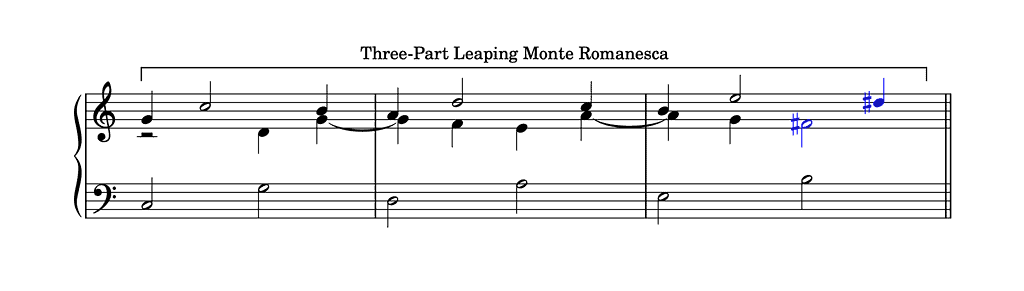

When the second note of the rising fifth in the bass of the third segment is set with a perfect fifth, the Leaping Monte Romanesca indeed consists of three segments. However, to get a perfect fifth, ➍ must be chromatically raised, resulting in a tonicized third segment. The third is usually also chromatically raised, acting as a temporary leading note:

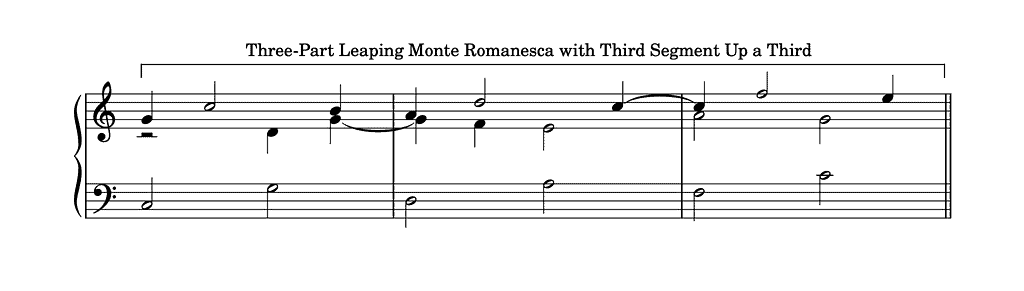

To avoid this mandatory deviation from the main key, the third segment of a Leaping Monte Romanesca could be a third rather than a step higher than the second. As such, it consists of a ④–① snippet, ending with the same scale step in the bass as the Leaping Monte Romanesca begins with.

In his book Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters, Job IJzerman argues that a canonic three-part Leaping Monte Romanesca with a third segment up-a-third “is no option: the canonic voice leading resists any irregularly” (IJzerman (2018, p. 122). While a rigorous canonic treatment of the upper parts is indeed not feasible, the example above illustrates that a modified canon can be continued during the third segment.

Note

- that a two-and-a-half-part and a three-part Leaping Monte Romanesca can also be tonicized (not shown).

- how closely related this variant of the Leaping Monte Romanesca is to the Leaping Romanesca. Both schemata consist of three segments, with the first and third consisting of the same bass notes.

Structural Use

As Rice explains in his article, a (Leaping) Monte Romanesca is often used to set up an important cadence. Certain composers, including Johann Sebastian Bach, also used the Monte Romanesca to start compositions.

For repertory examples of the Monte Romanesca see Rice’s article (https://www.academia.edu/32429345/) and his YouTube video:

See also my essay on disjunct moti del basso.

Further Reading (Selection)

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Rice, John A. Climbing Monte Romanesca: Eighteenth-Century Composers in Search of the Sublime (Unpublished Essay, 2017), https://www.academia.edu/32429345/ (accessed 5 March 2024).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).