Another early topic within partimento training is what is commonly known today as the rule of the octave.

The rule of the octave suggests one specific, first-choice chord for each note of a major and minor scale in the bass, both ascending and descending. While different versions of the rule of the octave exist, I focus in this essay on the standard one in major that Fedele Fenaroli taught.

The term ‘rule of the octave’ was not used in 18th-century Italy —this rule was referred to as setting scale (scales). Still, because it is a convenient term, I do use it throughout this essay, represented by the abbreviation “RO”.

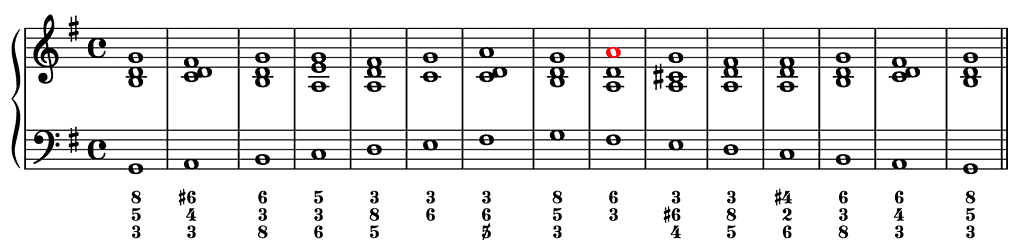

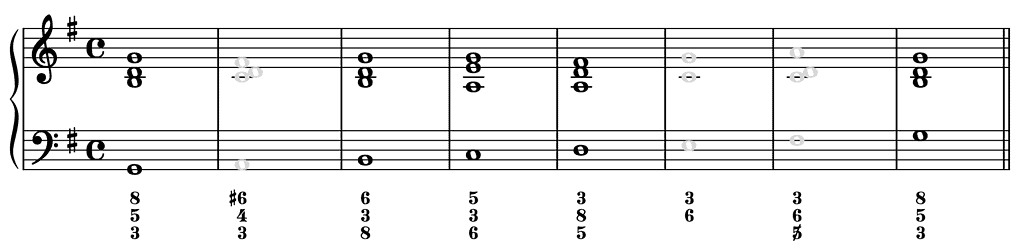

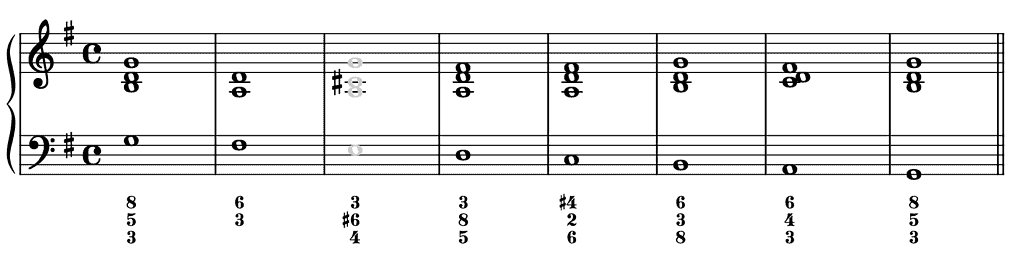

Interestingly, voice leading was not an issue when Fenaroli taught his students the RO. At this point, the RO was simply used to assimilate a harmonic framework, to grasp the essential vertical sonorities on each note of a major and a minor scale in the bass, both ascending and descending. Have a look at the following example.

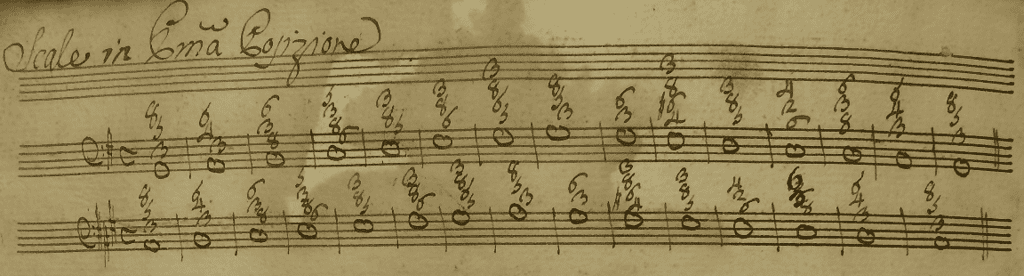

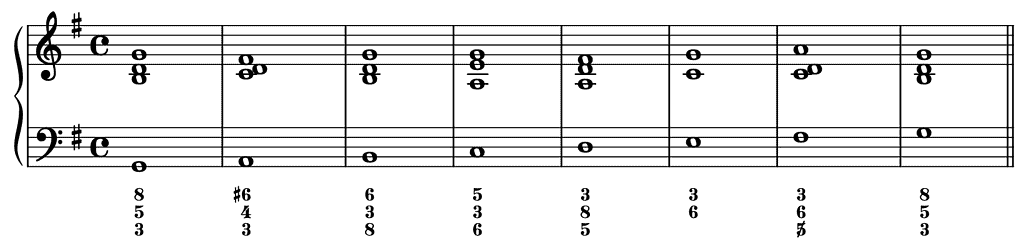

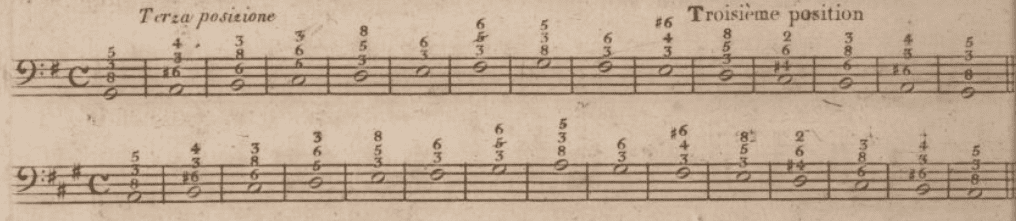

PARTIMENTI FENAROLI, I-Bsf FN. F. I. 1, fol. 1v

This example is an excerpt from the many manuscripts with the musical examples to which Fenaroli’s primer Regole Musicali refer. It shows the RO of G major and A major scales in the bass, both ascending and descending. The figures above the bass line are a stenographic notation for exactly which notes should be played on each bass note. This can be seen from the fact that the figures are not always notated in ‘logical’, descending order.

Note

- how the number of parts changes, from three to five parts (including the bass)

- that parallel octaves are not avoided (see for instance the realization from ⑤ to ⑥ in the ascending scales, indicated by an “8” as second figure above both notes)

- that doubling of the leading note is not avoided (see for instance the realization of ⑦ in the ascending scales, indicated by the “8” as second figure above the leading note)

Indeed, these figures confirm that students didn’t really need to be concerned with voice leading at this stage (apart perhaps from the top voice). Instead, they had to familiarize themselves with the first-choice sonority on each bass note in scalar passages.

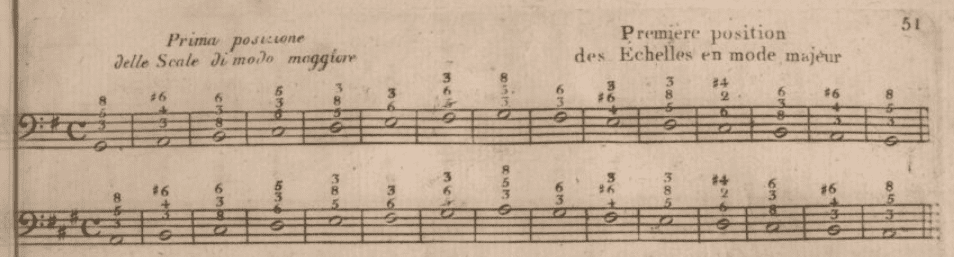

The earliest source related to Fenaroli that I know of that does consider voice leading (in all voices) in relation to the RO is the bilingual Partimenti Ossia Basso Numerato, Opera Completa Di Fedele Fenaroli Per uso degli alunni del Regal Conservatorio di Napoli edited by Emmanuele Imbimbo and published by Raffaele Carli in Paris in 1813 or 1814. (For more information on this source and how it relates to Fenaroli see the preface to my critical edition of Fenaroli’s partimenti and my article On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update from 2018.) This source gives the RO in three positions based on a four-part texture, with an occasional three-part sixth chord. First position means starting on ➊ in the top voice, second position on ➌, third position on ➎.

While Fenaroli does not seem to have used these four-part versions at the beginning of his teaching practice, I do find them useful when teaching students today.

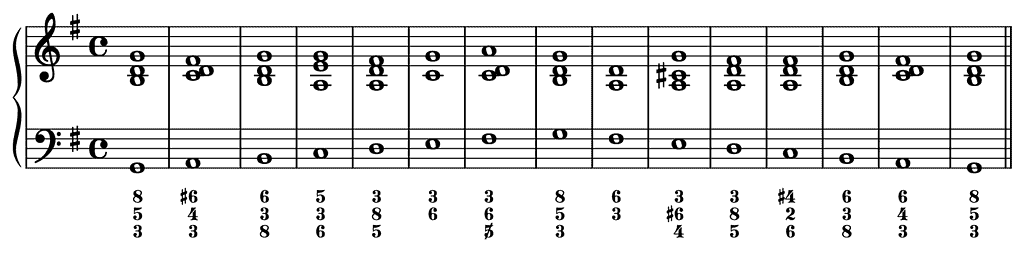

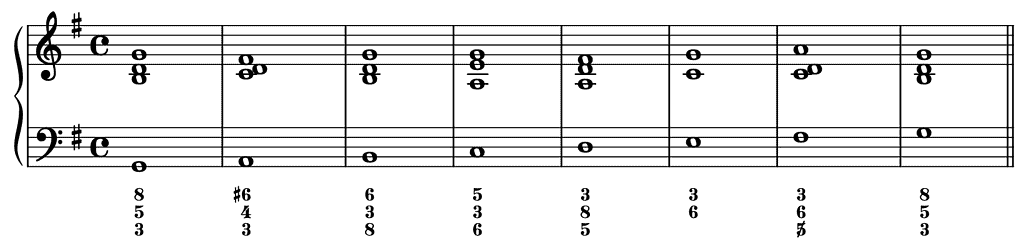

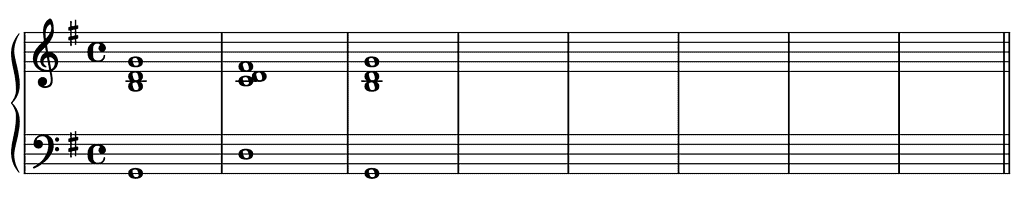

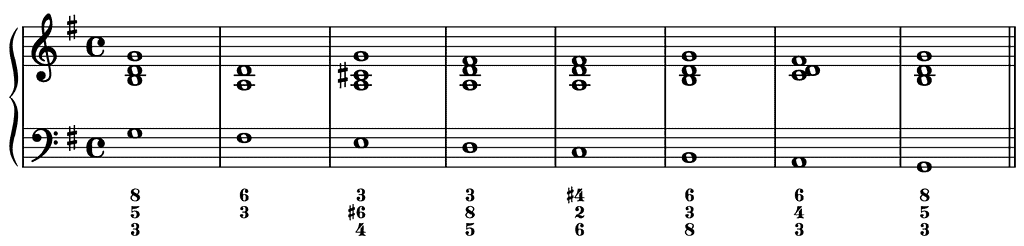

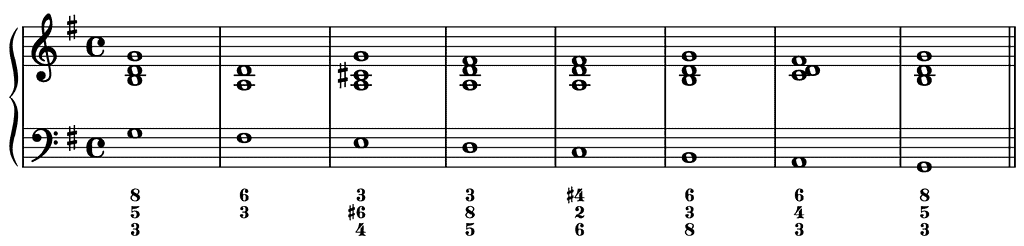

Complete RO in First Position

The example below illustrates the RO for the same two scales in first position as the example above, G major and A major.

Note that there are no more five-part chords and that the voice leading does not contain (or hardly) any issues. The next example concretizes the figures of the G major scale in first position:

On page 121 of this Art of Partimento (2012), Giorgio Sanguinetti gives a realization of this scale in first position according to Imbimbo as well. While his realization is almost identical to mine, he gives a1 as top note of the setting on ⑦ in the descending scale, resulting in a four-part instead of in a three-part chord at that point.

While this realization is of course blameless, it does not translate the figures literally. As a matter of fact, all the manuscripts I know give 6/3 at that point.

Ascending RO in First Position

Let’s have a closer look now at the individual chords of the RO and let’s focus first on the ascending major scale.

Note that

- A triad occurs on ① and ⑤, making these scale steps stable.

- Before both scale steps, a 6/5/3 chord occurs, making ④ and ⑦ unstable, mobile.

- ③ is partially stable and preceded by an unstable chord as well, in this case a 6/4/3 chord on ②.

- The RO can be divided into two sections, of which the first section can be further divided into two subsections. The realization of the first five scale steps constitutes a first section, as both hands basically remain in the same position. This section can be further divided into the realization of ①–②–③ (with the same chord on ① and ③) and the realization of ④–⑤ (a half cadence). The second section consists of ⑤–⑥–⑦–①. Between ⑤ and ⑥, both hands usually move up.

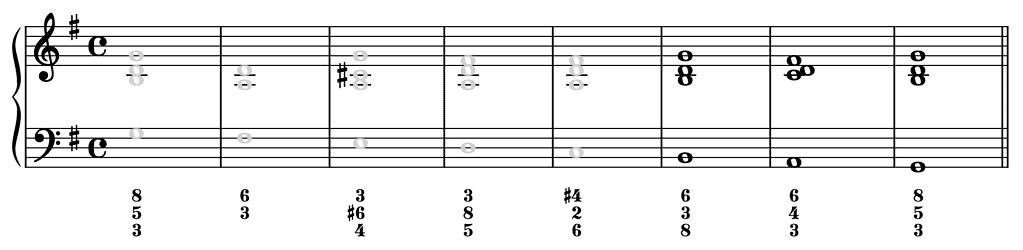

How to Build Up the Ascending RO in First Position?

One can see the RO as an extension of a simple cadence. (For more information on the simple cadence —or cadenza semplice— see my essay Cadences: The Basics.) Just omit ②, ③, ④, ⑥ and ⑦ from the complete scale, and you get a simple cadence —I have greyed out these scale steps and corresponding chords in the example below.

Now you are ready to fill in gradually the gaps. First, insert ③ in between ① and ⑤. This is the easiest step since the chord you play on ③ is the same one as the chord on ①:

Note that the bass note is doubled in the chord on ③, which was the standard thing to do then. (Modern theory tends to prohibit/avoid this, favouring the doubling of the sixth or of the third.)

Next, insert ④ in between ③ and ⑤. The easiest way to find the 6/5/3 chord that goes on top of ④ is to think “I play a triad to which I add the sixth”. In other words, locate first the third and the fifth of the chord, then the sixth:

The last scale step to be inserted to complete the first section of the ascending RO is ②. The 6/4/3 chord can be easily found when thinking of the simple cadence with a seventh chord on ⑤. As a matter of fact, the realization of that type of simple cadence and of the first three scale steps of the ascending RO is identical.

This is a simple cadence with a seventh chord on ⑤ in G major:

And here you can see how the right hand of the first three scale steps of the ascending RO is identical with that of the example above:

At this point, make sure to practice the simple cadence with a seventh on ⑤ and the first three scale steps of the ascending RO alternately.

Let’s get into the second section of the ascending RO now. Only two more scale steps need to be added and realized to obtain a complete scale. I recommend first inserting ⑦ in between ⑤ and ①:

Note that the succession of the pure fifth a-d (on ⑤) and the diminished fifth f♯-c (on ⑦) is not an issue. Make sure to the play thrice the d1 in the right hand with the index finger.

Finally, insert ⑥ in between ⑤ and ⑦. As the example below illustrates, ⑥ is not realized as a triad but as a sixth chord. The reason for this is that the sixth prepares the diminished fifth on ⑦. (A ⑤–⑥ progression that doesn’t progress to ⑦, however, is usually realized as a broken cadence with a triad on both scale steps, contrary motion between the upper voices and the bass while the leading often rises. I will come back to this in my essay When the Rule of the Octave Does Not Apply.)

Note that both hands change position at the moment of the ⑤–⑥ progression. I recommend that you play the sixth chord on ⑥ with 1 and 4 in the right hand.

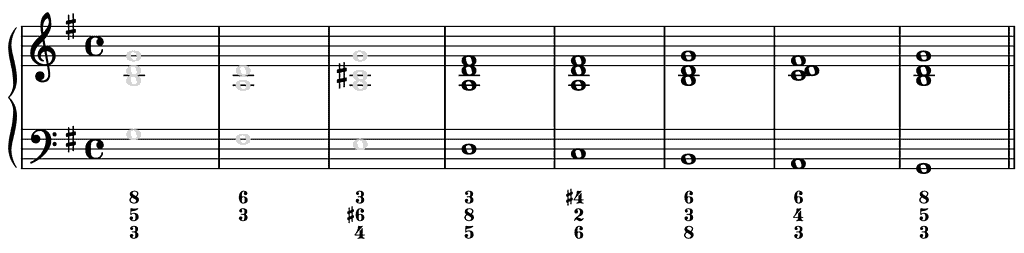

Descending RO in First Position

Now that we have seen the complete ascending RO, we are ready to get into the descending RO. This is the complete descending RO in G major:

How to Build Up the Descending RO in First Position?

Let’s start with the easy bit. While the descending RO contains quite some different chords than those of the ascending RO, one snippet is identical in both the ascending and the descending RO. The realization of the first three scale steps of the ascending RO (①–②–③) and that of the last three scale steps of the descending RO (③–②–①) is identical.

Make sure to practise both snippets in loop, that is, (①–②–)③–②–①–②–③–…

Now start on ⑤. Notice that the chord to be played on this scale step is identical to the chord you played on that scale step in the context of the ascending RO, that is, a triad with the third —the f♯— in the top voice. When descending to ④, however, the chord on that scale step is different than the chord you played on ④ when rising to ⑤. Instead of playing a 6/5/3 chord, just hold down (or repeat) the same chord you played on ⑤. Easy!

This brings us to the more difficult snippet of the descending RO: its beginning. Important to observe first is that ⑦ obviously doesn’t rise to ① but descends to ⑥. If one were to play a 6/5 chord (the fifth being diminished), as one does in the ascending RO, one would be in trouble. After all, the presence of the diminished fifth demands the bass to rise to ①. Therefore, a diminished fifth on ⑦ cannot be included in the chord when ⑦ proceeds to ⑥. This is the reason why a (three-part) sixth chord (without diminished fifth) is played on ⑦. The opening chord is obviously a triad with ➊ in the top voice.

The final chord we have to determine is the one on ⑥. Although we are dealing here with the descending RO for the G-major scale, the chord that is to be played on ⑥ —3/♯6/4— doesn’t belong to that key. It rather casts a glance at D major.

It can help to think of what the right hand would be playing in the context of a simple cadence in second position in D major. Indeed, the chord on ⑥ in the right hand is a dominant seventh chord in D major.

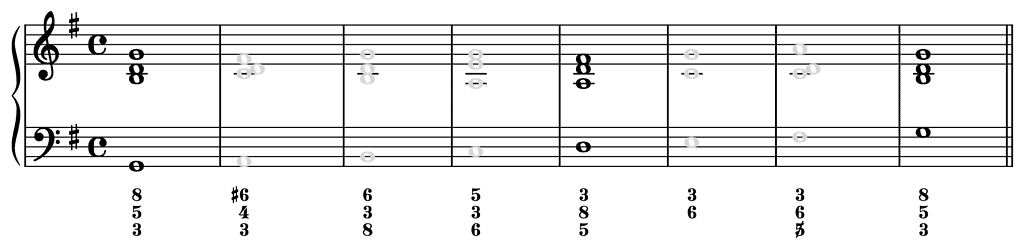

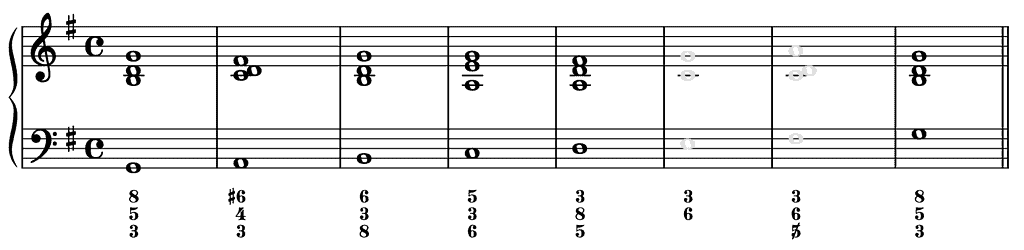

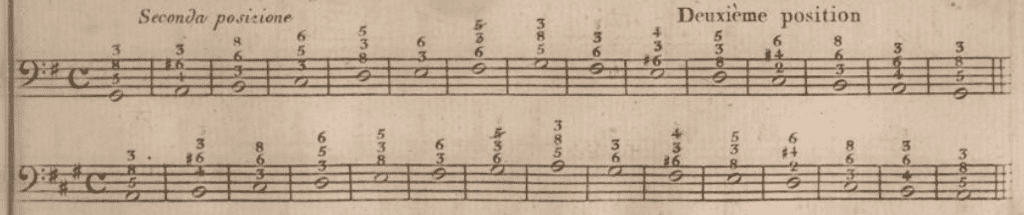

Complete RO in Second Position

The example below illustrates the RO for G major and A major in second position from Imbimbo’s edition.

The next example concretizes the figures of the G major scale in second position:

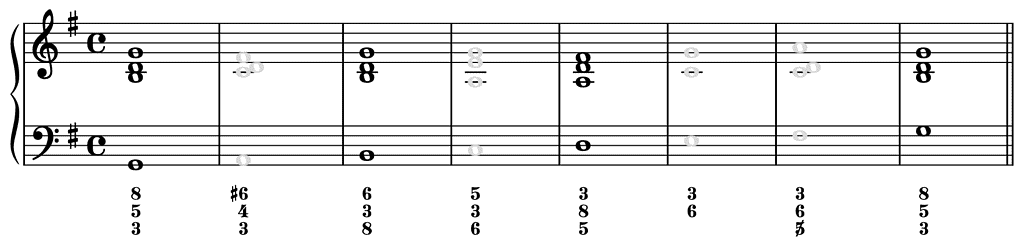

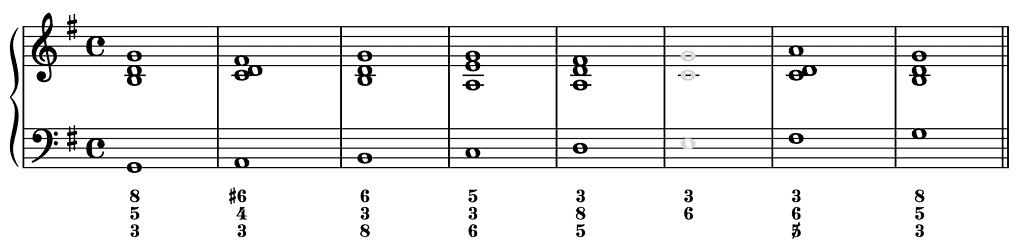

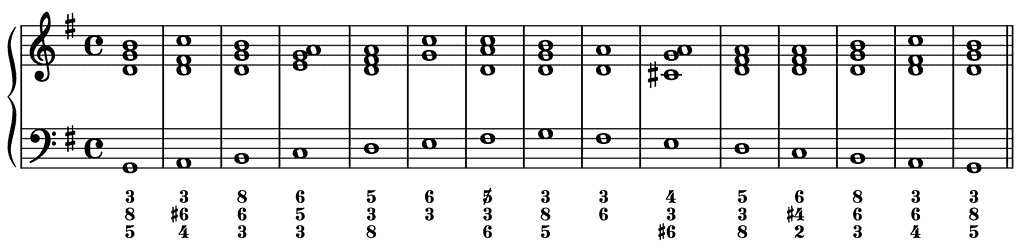

Complete RO in Third Position

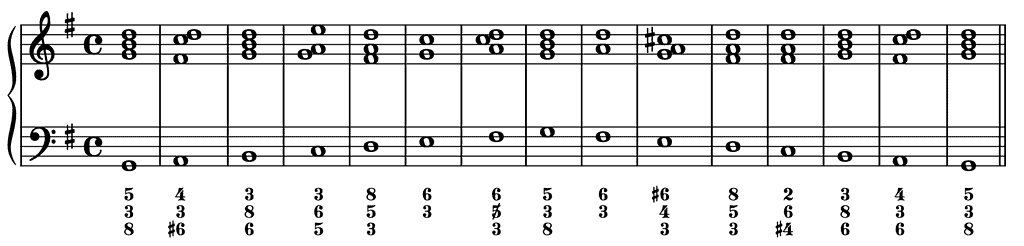

The example below illustrates the RO for G major and A major in third position from Imbimbo’s edition.

The next example concretizes the figures of the G major scale in third position:

Further Reading (Selection)

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207-229.

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE, Preface and Editorial Principles by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. Partimenti Ossia Basso Numerato, Opera Completa Di Fedele Fenaroli. Per uso Degli alunni del Regal Conservatorio di Napoli (Paris: Imbimbo & Carli, 1813 or 1814).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).