Like the Romanesca, the Do-Re-Mi —the term comes from Robert O. Gjerdingen— was a favourite opening schema in the galant style that also existed in several variants.

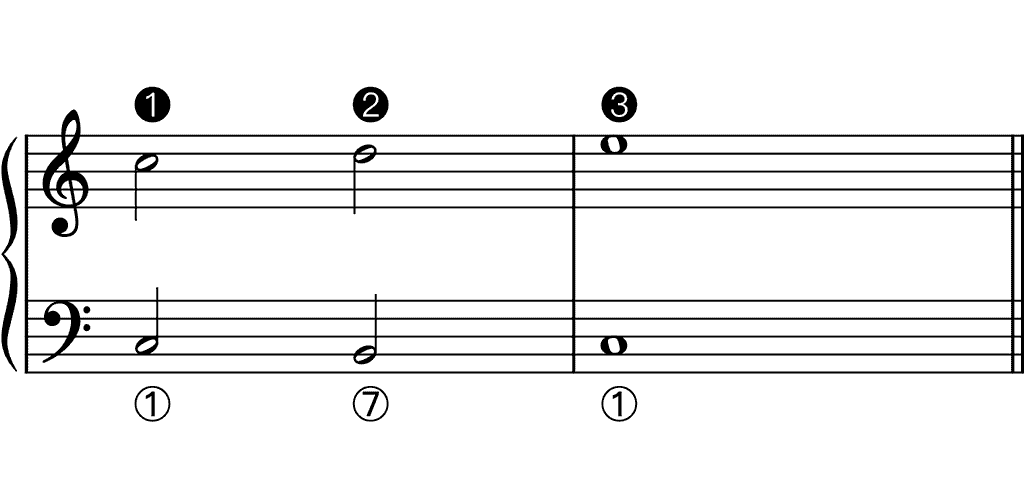

The term Do-Re-Mi refers to a proposta schema often featuring a ➊–➋–➌ snippet in the melody and a ①–⑦–① snippet in the bass.

This essay will explore several types of the Do-Re-Mi in melody and in bass.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the melody (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①).

Do-Re-Mi in the Melody

When the Do-Re-Mi appears in the melody, two possibilities are common in the bass as a counterpoint:

- Do-Si-Do (①–⑦–①)

- Do-Sol-Do (①–⑤–①)

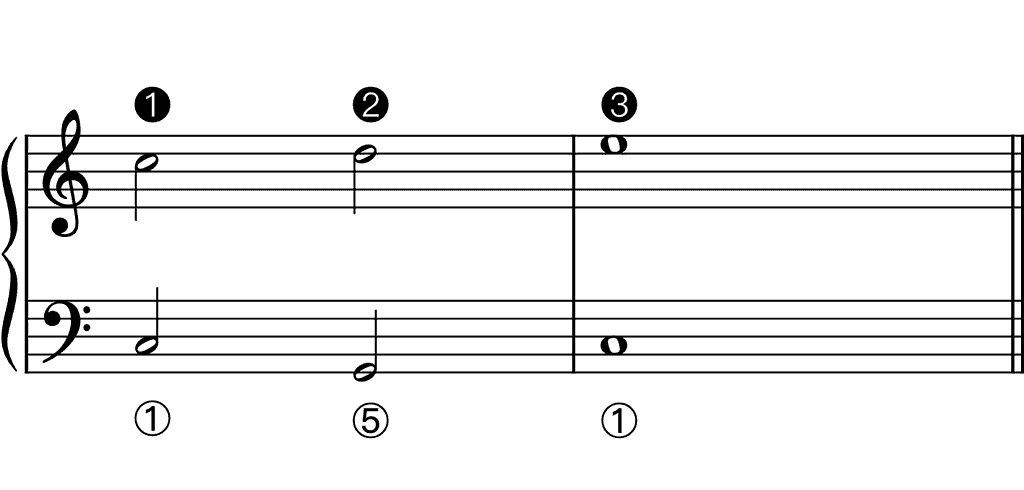

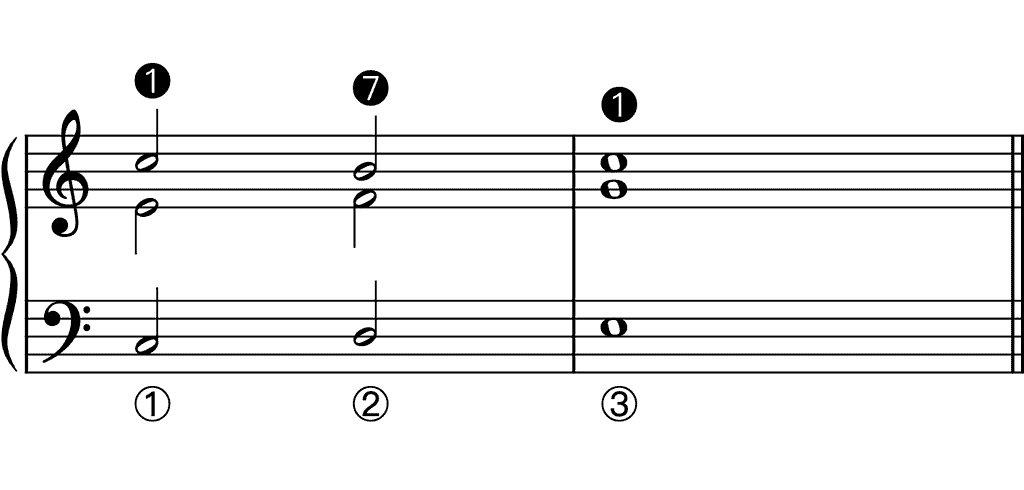

Do-Si-Do in the Bass

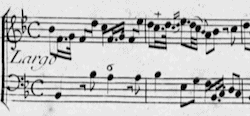

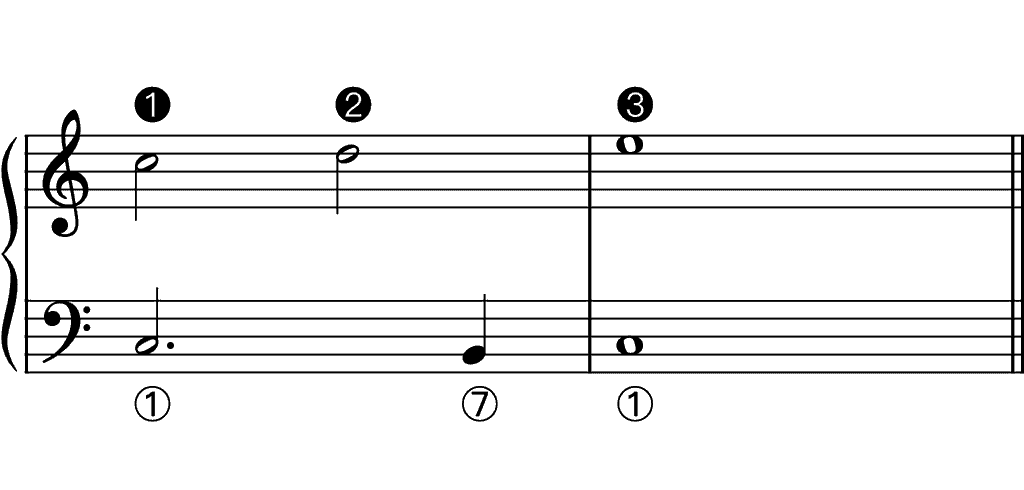

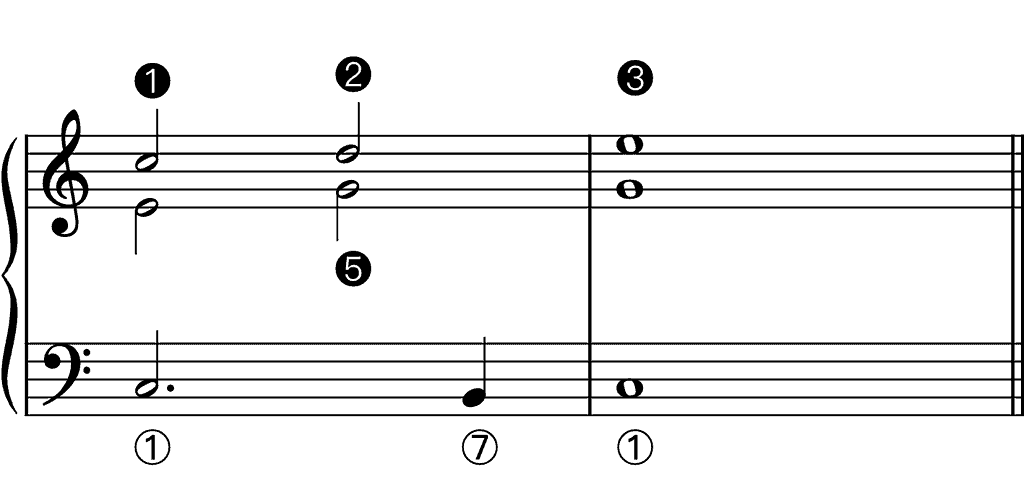

In his book Music in the Galant Style, Gjerdingen opens his chapter on the Do-Re-Mi with a version in which the ➊–➋–➌ snippet in the melody is accompanied with a ①–⑦–① snippet in the bass:

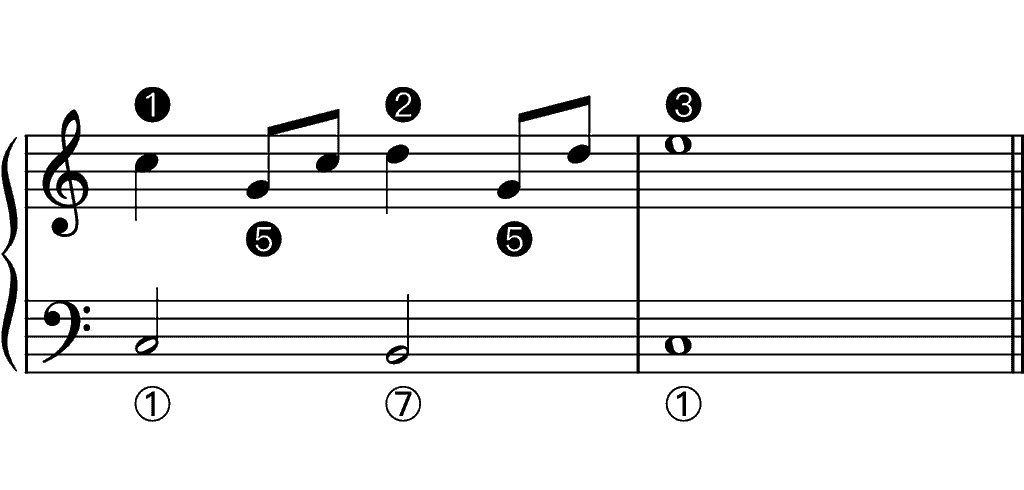

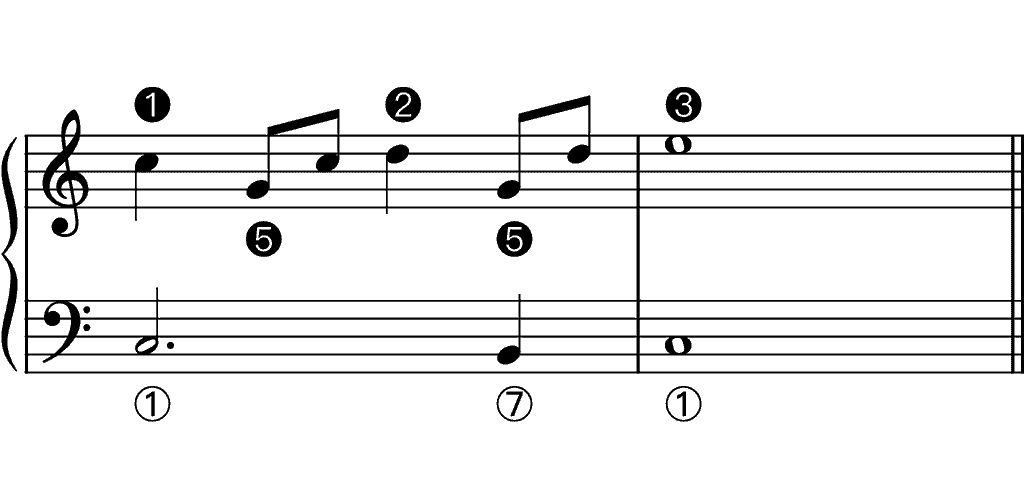

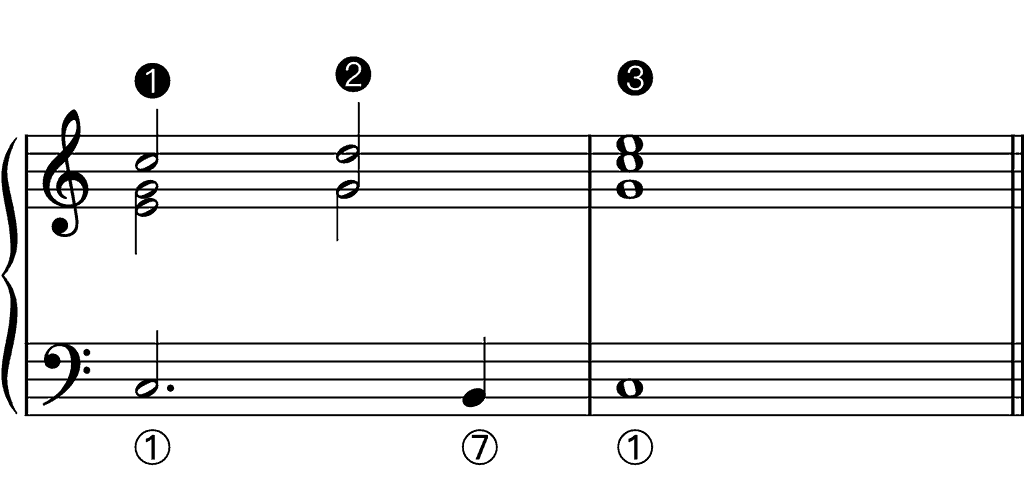

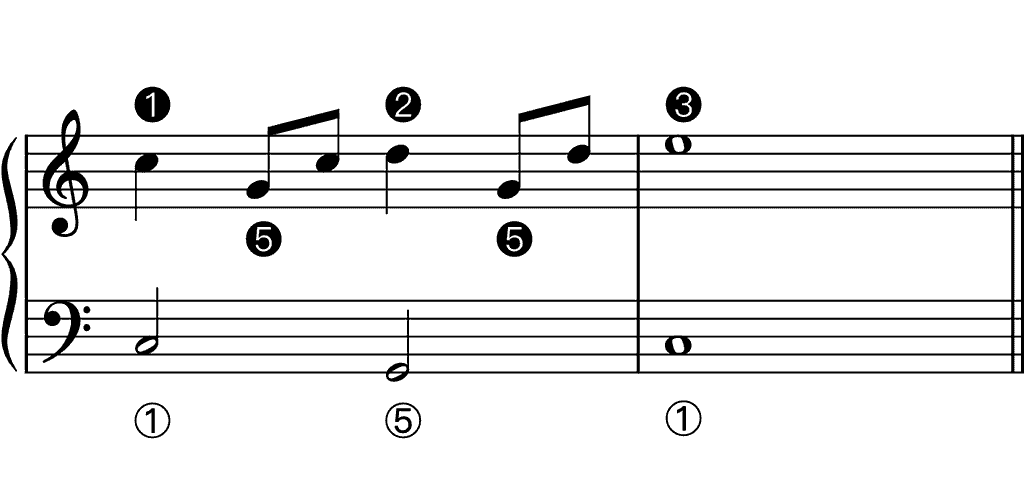

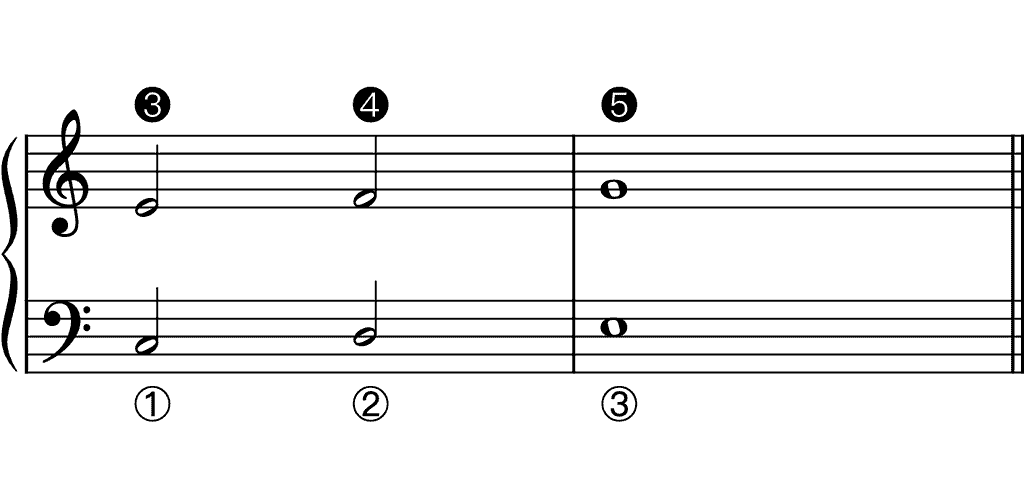

The melody is often embellished with what Gjerdingen calls Adeste Fidelis leaps:

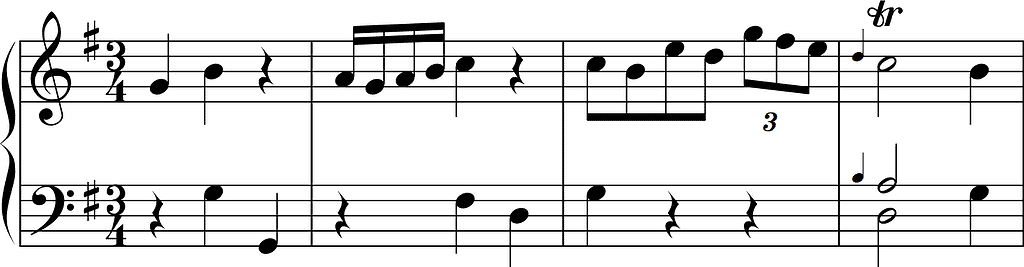

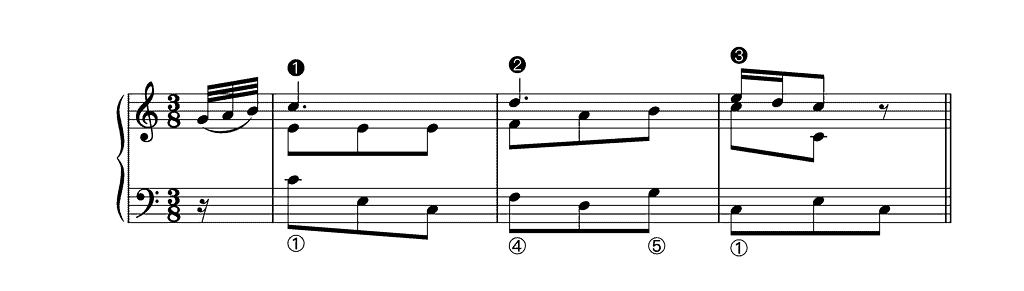

Below you can see how Domenico Cimarosa uses this type of Do-Re-Mi to open one of his many one-movement keyboard sonatas:

As Gjerdingen notes, Cimarosa regularly combines a Do-Re-Mi not only with Adeste Fidelis leaps but also with an implied melody in parallel thirds (compound line), which suggests “that he considered this a unitary package—a Gestalt” (Gjerdingen (2007), p. 85).

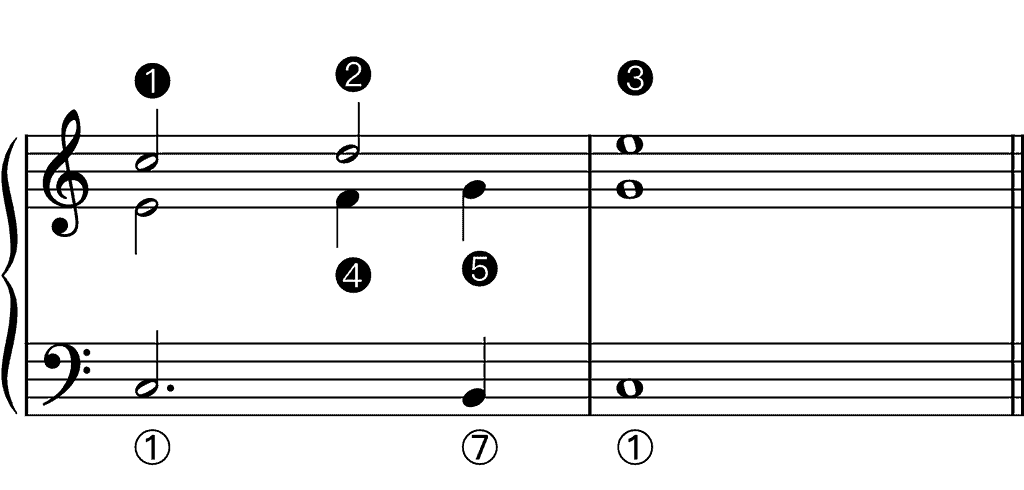

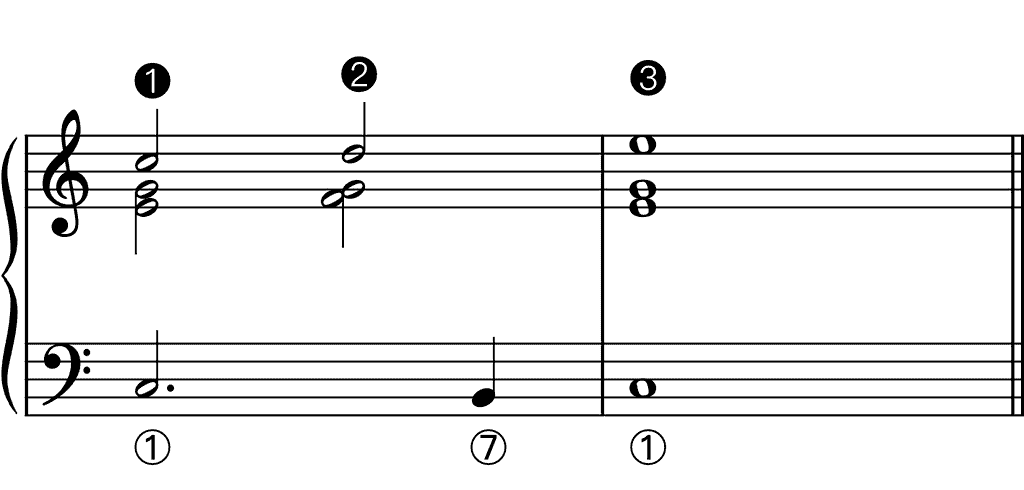

The following example illustrates how Joseph Haydn uses a Do-Re-Mi with an implied melody in parallel thirds but without the Adeste Fidelis leaps to open one of his keyboard minuets:

Do-Si-Do in the Bass with a Suspension

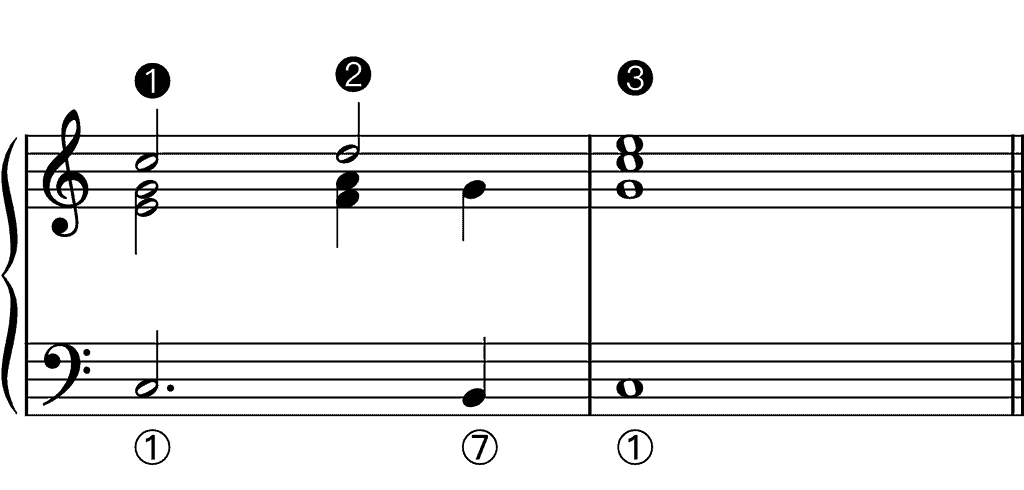

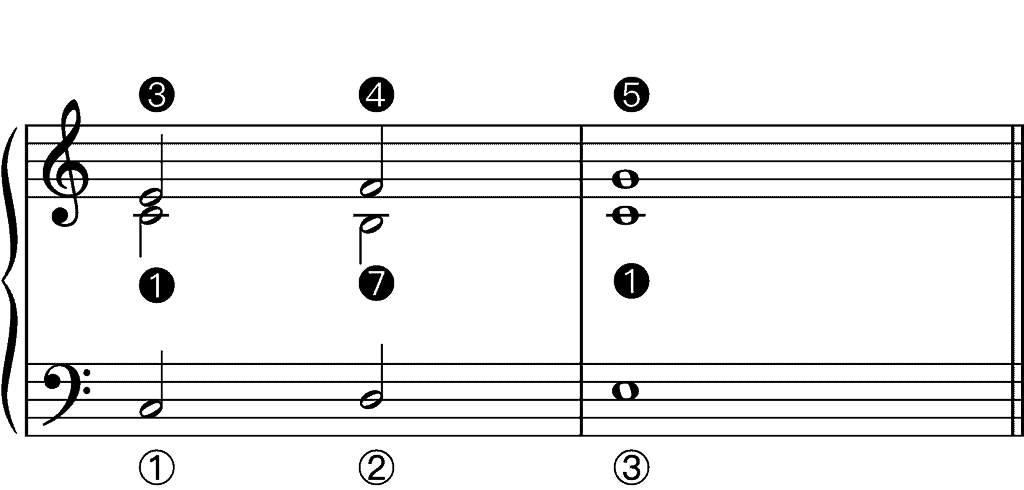

In the models and examples that we’ve seen so far, both parts move simultaneously to the next (structural) note. However, the second structural note in the bass can also sound later, creating a vertical second on the moment of the second structural note in the upper part:

In a three-part setting, a vertical fourth or fifth can be added to this vertical second, resulting in a 4/2 or a 5/2 sonority, respectively:

Note that in the middle voice of the first example, ➍ rises to ➎ above ⑦. If ➍ had remained in place above ⑦, it wouldn’t have been able to ➎ above ① but should have had to step down to ➌, resulting in an unsatisfactory doubled third.

In a four-part setting, this moment can be set in three different ways:

- As a 5/2 sonority (Interestingly, in the second volume of his treatise from 1762 dealing with accompaniment, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach states that this sonority “always sounds empty regardless of whether it is realized in three or four parts. It is made sonorous by its resolution. Rare in the galant style, it is more frequent in learned works and in company with syncopations (in der gearbeiteten [Schreibart], und bey den Bindungen). Consequently it is realized in four parts” (C.P.E. Bach (1762), p. 111, English translation in Mitchell (1951), p. 263).)

- As a 5/4/2 sonority (note that a 5/4/2 sonority results in a doubled third on the final ①, which isn’t a problem thanks to the presence of the fifth)

- As a 6/4/2 sonority

Do-Sol-Do in the Bass

A Do-Re-Mi in the melody can also be combined with a Do-Sol-Do in the bass, giving this setting more weight:

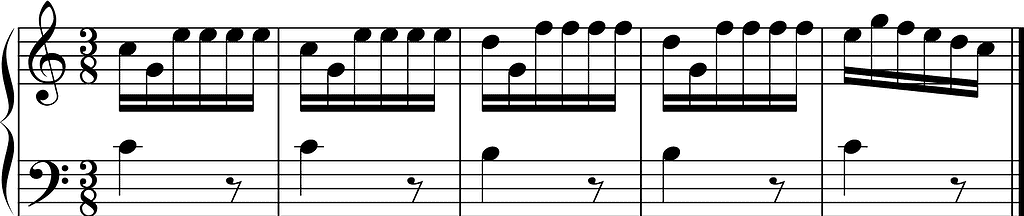

Haydn opens his Keyboard Divertimento in C major Hob. XVI: 7 with such a setting:

Note that the second ① in the bass is an octave lower than the first.

Do-Fa&Sol-Do in the Bass

The Re of a Do-Re-Mi in the melody can also be set with Fa&Sol (④–⑤) in the bass:

(top voice: violins 1 & 2, middle voice: viola, bass: BC)

Do-Re-Mi in the Bass

The Do-Re-Mi can also appear in the bass, with the following common counterpoints in the melody:

- Do-Si-Do (➊–➐–➊)

- Mi-Fa-Sol (➌–➍–➎)

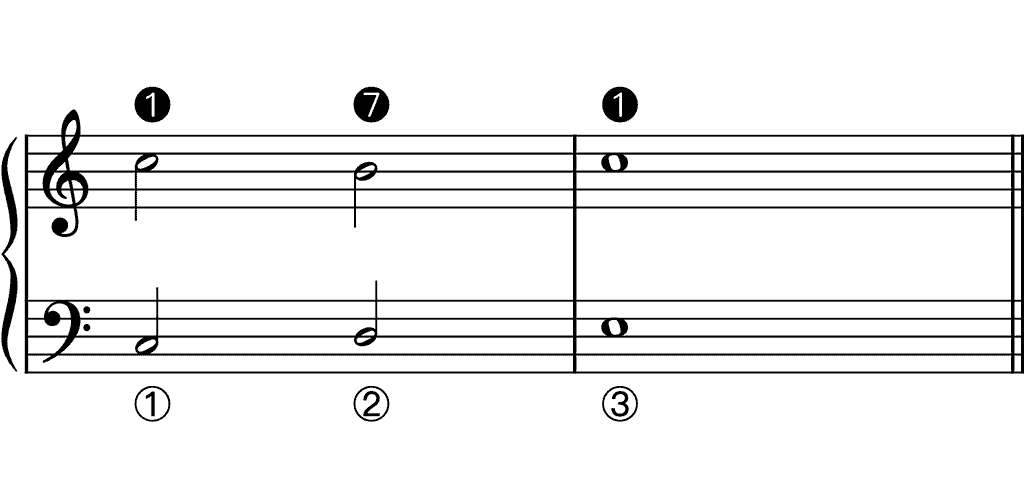

Do-Si-Do in the Melody

Since the combination of the Do-Re-Mi in the melody and the Do-Si-Do in the bass is written in invertible counterpoint, it is possible to swap the parts:

A middle part in parallel thirds with the bass can be added to this setting:

Mi-Fa-Sol in the Melody

It is also possible to use this middle voice in parallel thirds as a melody, both in a two- and a three-part setting:

With regard to the second example, note that

- The inner presents the ➊–➐–➊ snippet.

- The succession of a diminished and a perfect fifth wasn’t considered an issue if the setting is at least three-part and if this voice leading doesn’t occur in the outer voices.

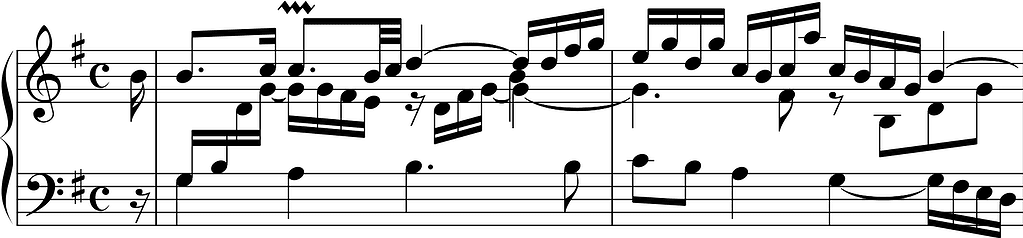

A well-known example of this variant is the beginning of the allemande from Johann Sebastian Bach’s French Suite No. 5 in G major:

Notice the ornamented ➊–➐–➊ snippet with suspension in the middle part.

Further Reading (Selection)

Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel. Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen — Zweyter Theil, in welchem die Lehre von dem Accompagnement und der freye Fantasie abgehandelt wird (Berlin, 1762).

Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel. Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments — Translated and Edited by William J. Mitchell (London: Cassell and Company Limited, 1951).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).