This essay deals with the third verset (i.e. short partimento) in D minor by Stanislao Mattei (1750–1825), which is the 55th verset in the collection and is numbered as such in the Wessmans edition.

The versets by Mattei are a remarkable collection of pedagogical pieces intended to be realized in three parts at the keyboard with great concern for contrapuntal quality. Moreover, instead of focusing on just one realization, students had to explore as many options as possible.

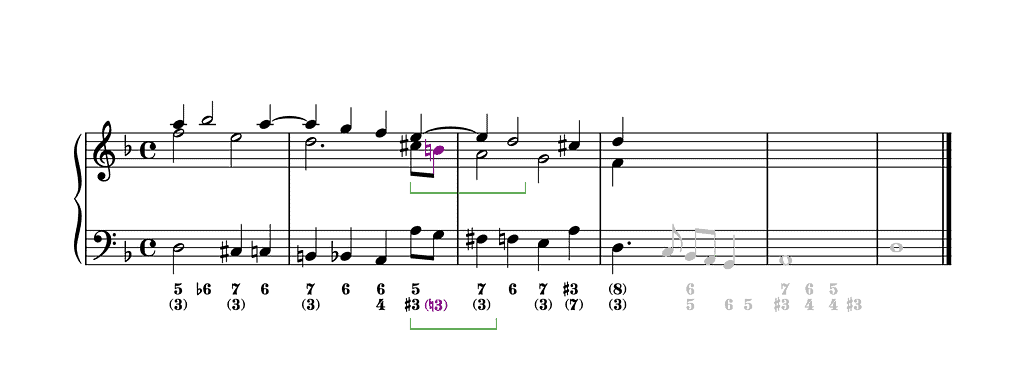

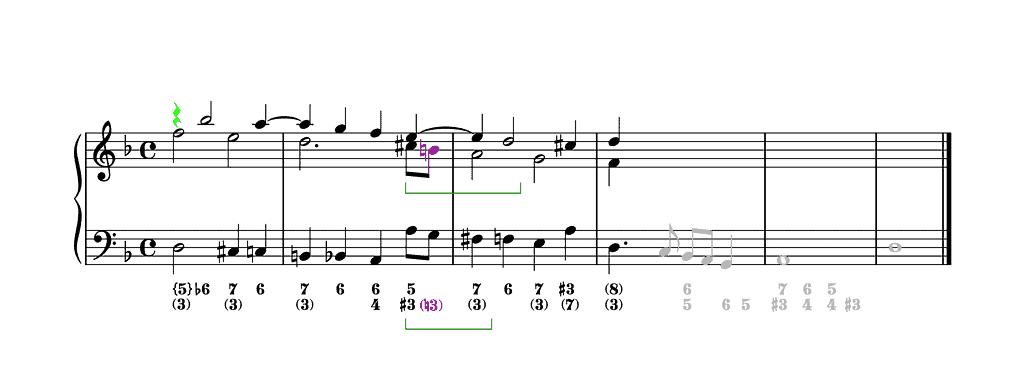

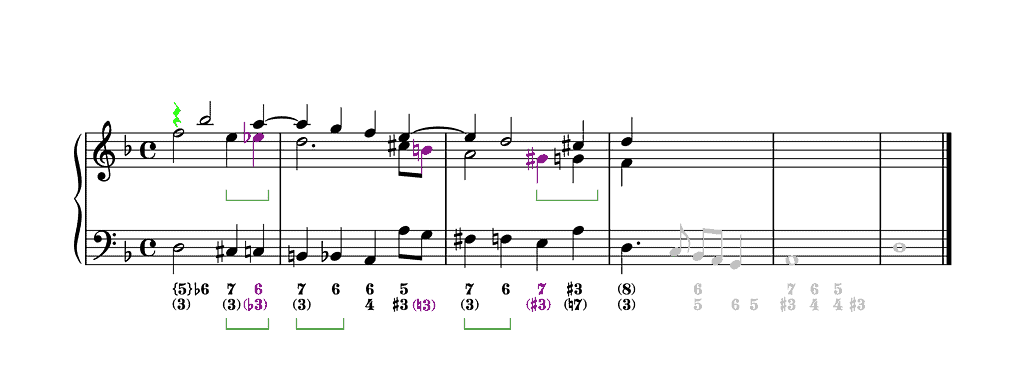

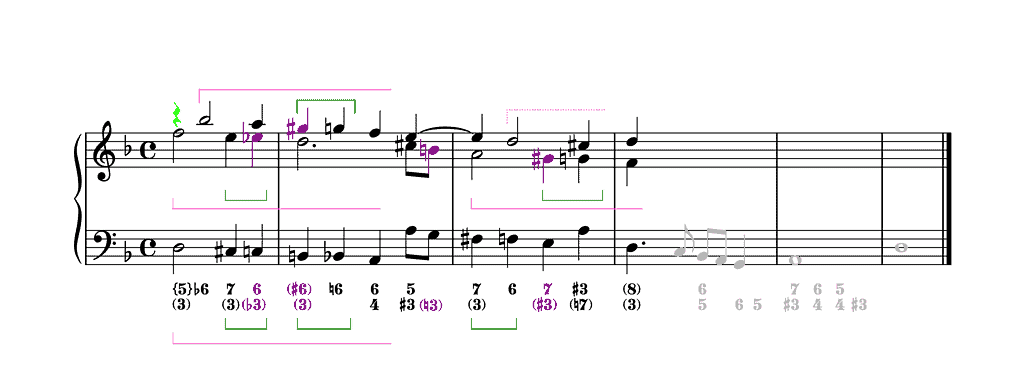

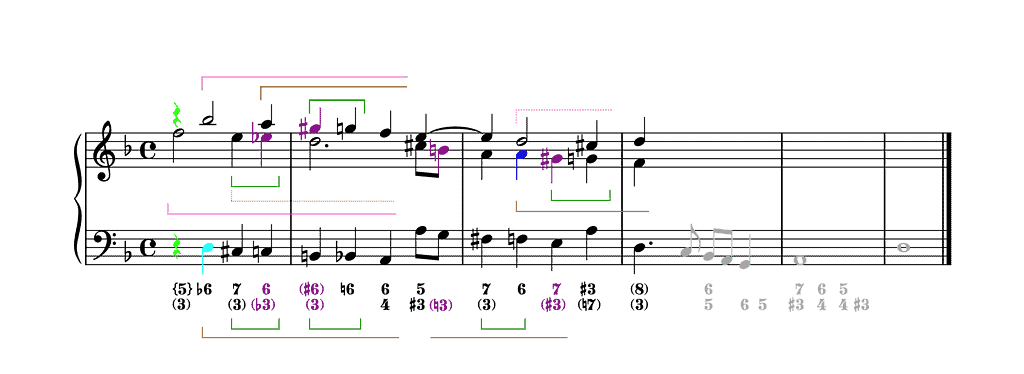

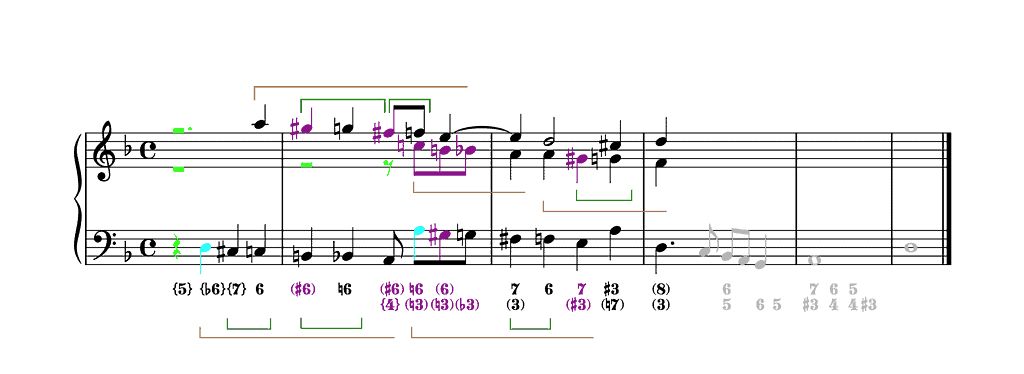

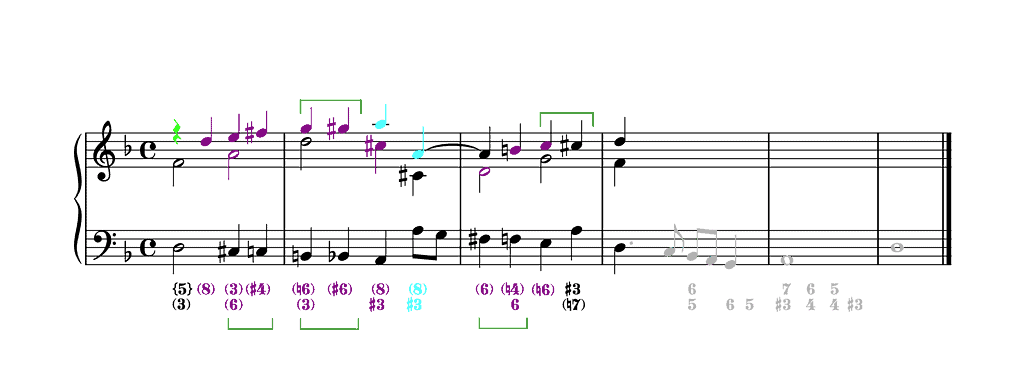

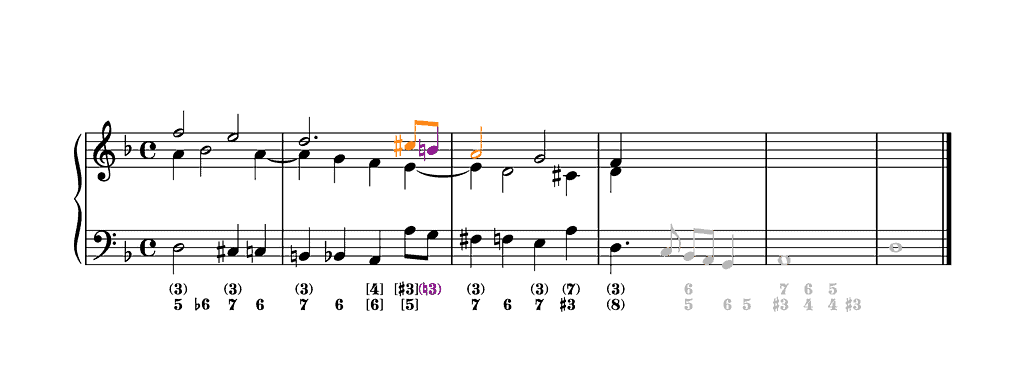

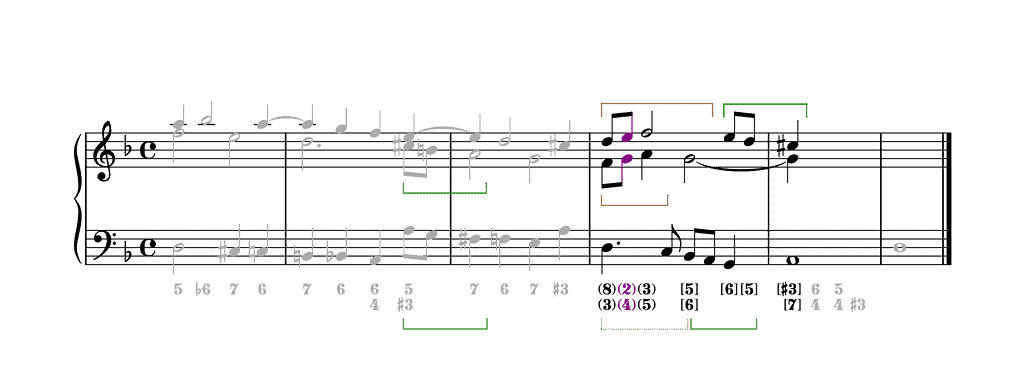

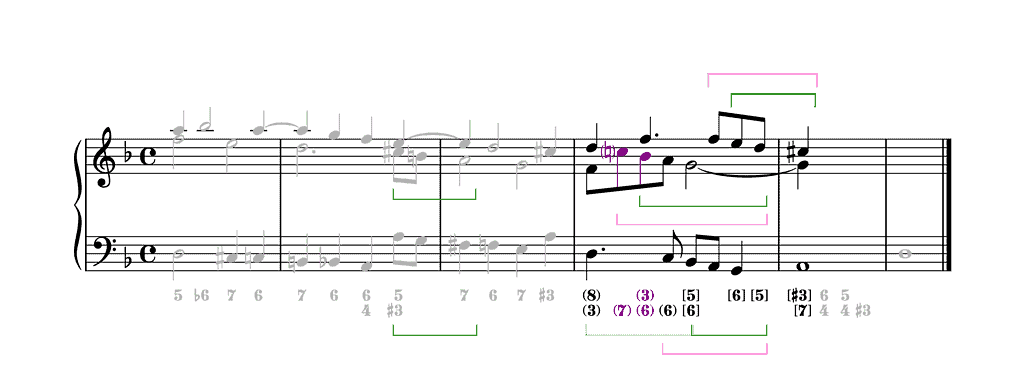

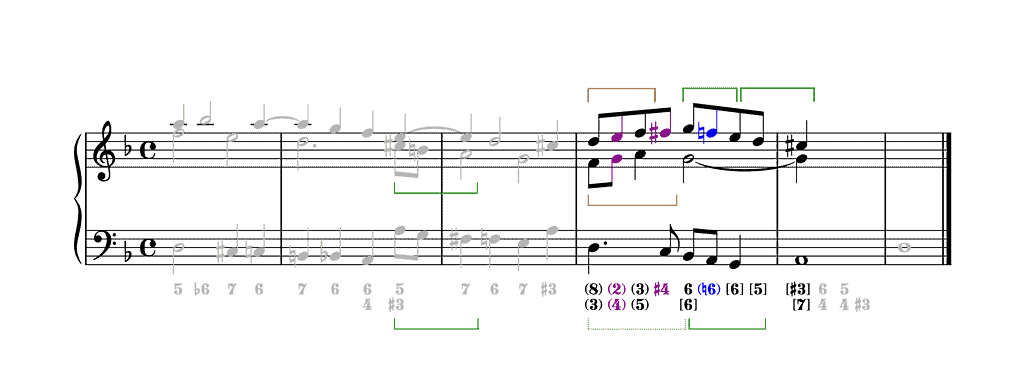

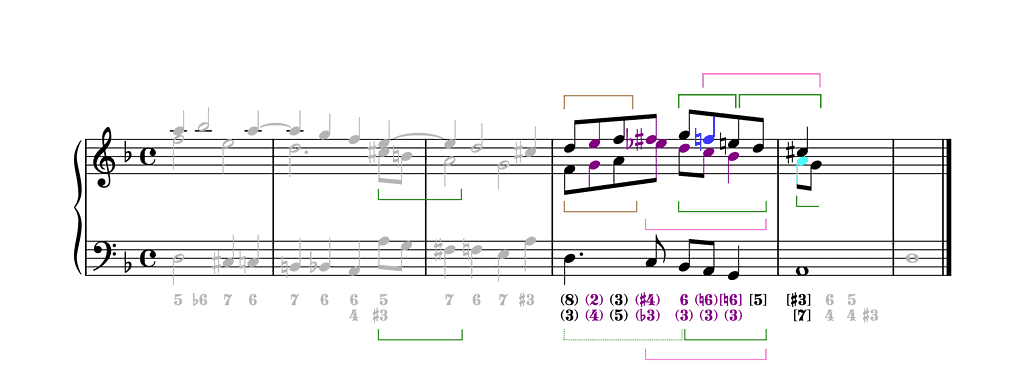

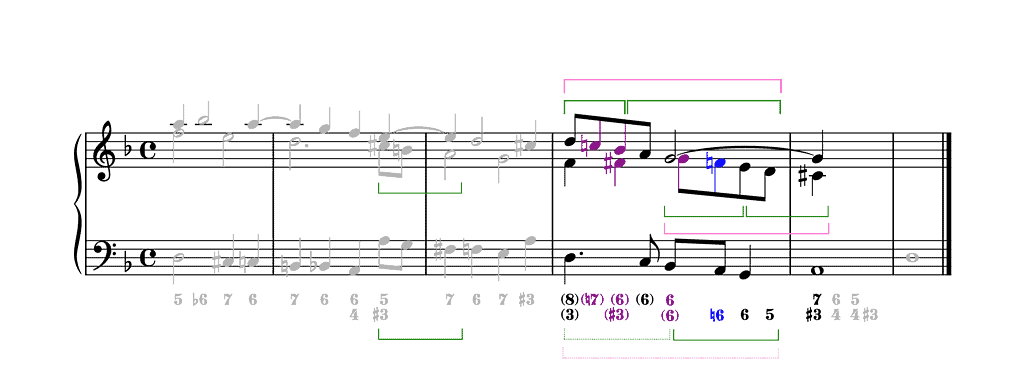

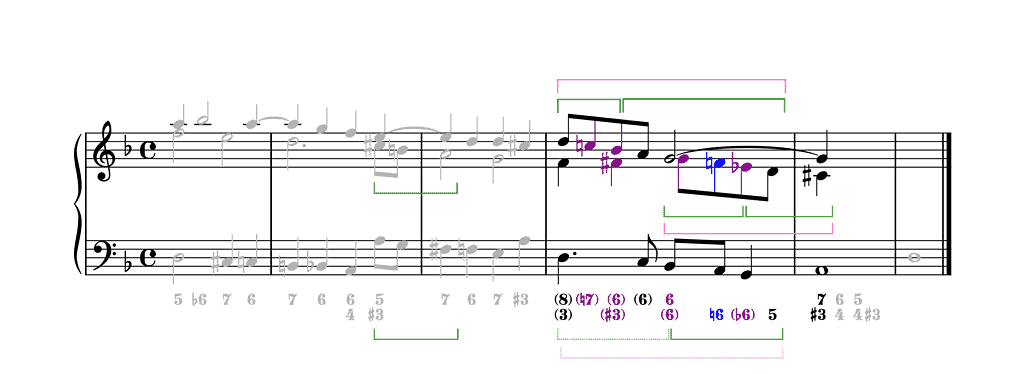

In the musical examples of this essay, I am using the following colour code:

- Orange: voice leading that is more or less/almost okay

- Purple: alternative version, changing the thoroughbass figures

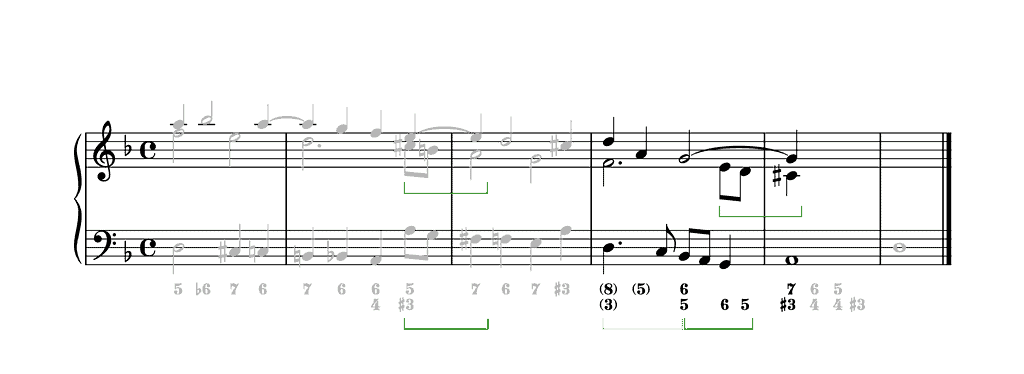

- Light green: a rest replaces a note (also in the bass)

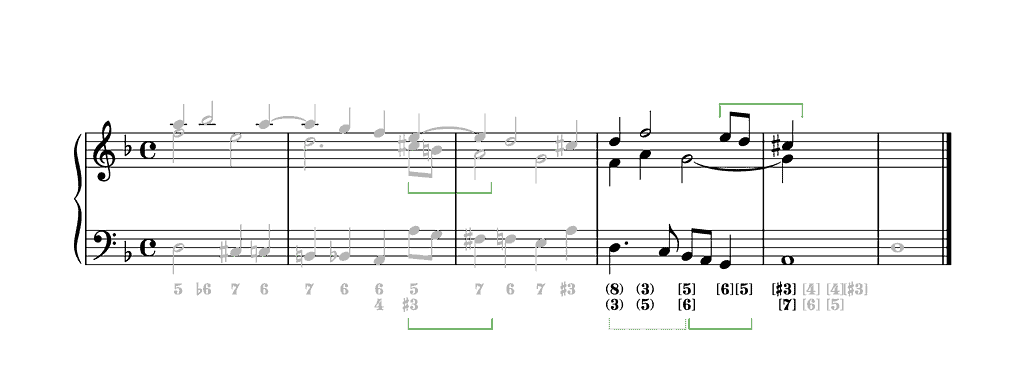

- Dark green hooks indicate a recurrent motive

- Pink hooks indicate another recurrent motive

- Brown hooks indicate a recurrent motive in melodic inversion

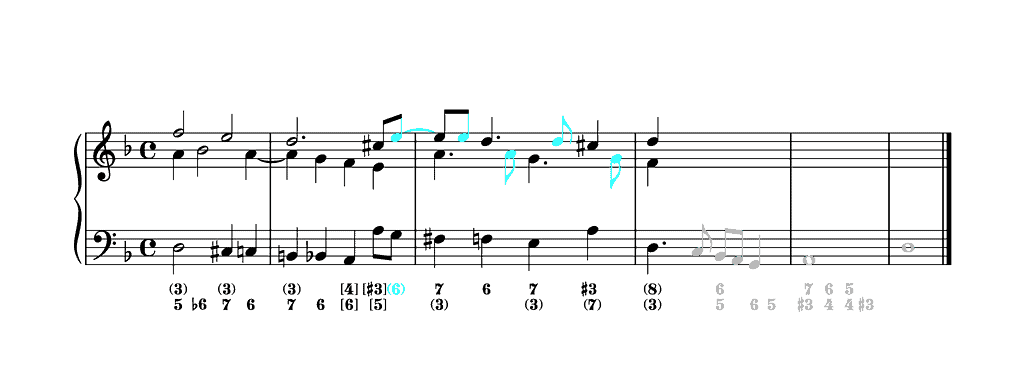

- Light blue: diminutions (also in the bass)

- Dark blue: something that is worthwhile looking at.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in an upper voice (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♯④ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ⑤

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Note further that

- ‘Bar 1a’ refers to the first half of bar 1, ‘bar 1b’ to its second half.

- I am using the Helmholtz pitch notation for naming musical notes. When I refer to notes without a specific register/octave, I use upper-case letters.

- In the musical examples throughout this essay, the thoroughbass figures as they appear in the 1824 edition are modified and made explicit to reflect exactly the voice leading and relative position of the upper voices.

- Thoroughbass figures between braces remain unrealized.

- Thoroughbass figures between parentheses are editorial. Those in black complete the given thoroughbass figures, those in purple propose an alternative version of Mattei’s, those in light blue include a chord factor that doesn’t appear in the given thoroughbass figures.

- Thoroughbass figures between brackets mean that they are ordered differently than those in the 1824 edition.

While I have written out all the musical examples in this essay, I strongly recommend reading only the thoroughbass figures as you play them through, only looking at the realization when in doubt. That way, you ‘think counterpoint’ instead of ‘notes’.

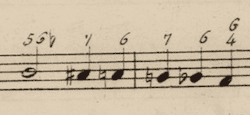

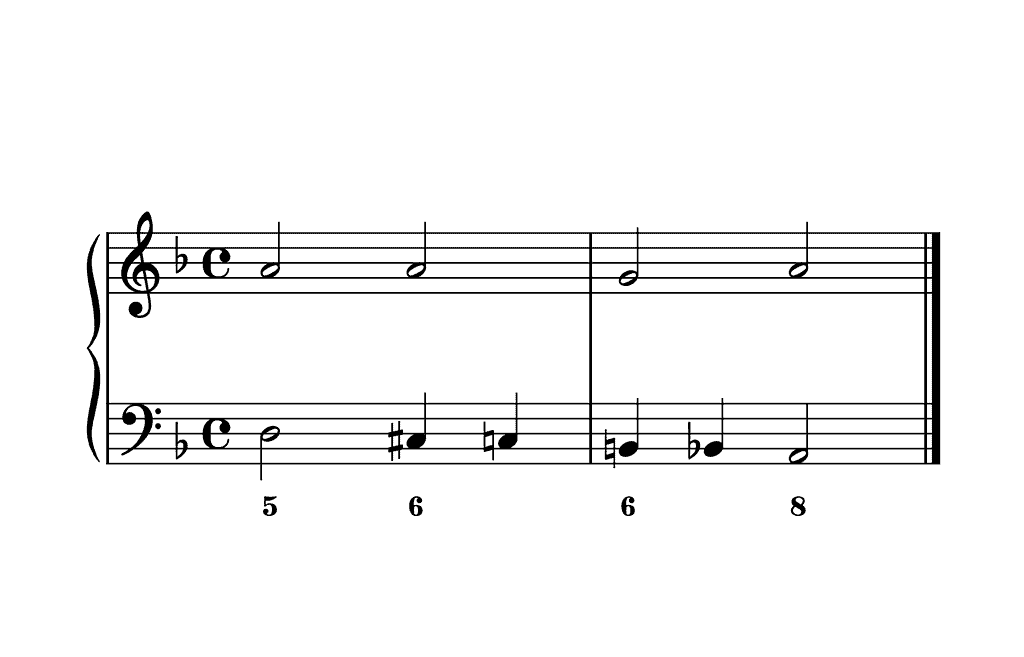

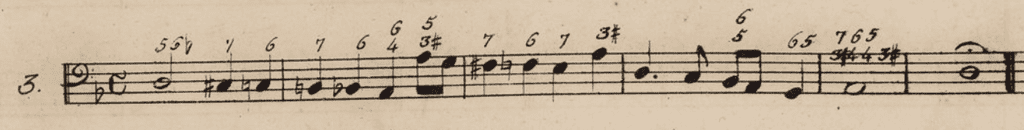

This is the unrealized third verset in D minor of Mattei from the 1824 edition:

Let’s look at the bass first. It begins with a chromatic fourth descending from ① to ⑤ (from d to A), a gesture often referred to today as a lament or lamento bass because of its regular —though not exclusive— association with affectations/feelings like sadness, grief or regret. The lament bass has long history, dating back to the 16th century and used regularly until well into the 20th century. (It goes without saying that settings of this bass evolve during that long period according to the specific musical language of the time.) This descending chromatic fourth is a typical example of what might be called a passus duriusculus.

In the Italian partimento and counterpoint tradition, the descending chromatic fourth can be set in several ways. (See also the section Moti del Basso That Descend Chromatically (aka Laments) in my essay Chromatic Moti del Basso.) In fact, one might argue, as William Caplin does in his article Topics and Formal Functions: The Case of the Lament, that the lament schema “is special: whereas most schemata embrace both an upper-voice melody and bass melody, the lament schema is defined essentially by its stepwise descending bass; no one melodic pattern emerges as a conventional counterpoint to this bass line” (Caplin (2014), p. 415–416). Still, both assessments in this sentence are somewhat of an oversimplification. On the one hand, Italian 18th-century partimento and counterpoint training was based on discovering and using as many good counterpoints as possible. Since the concept of variation was so highly valued, limiting oneself to only one common combination of one bass and one upper voice would go against the aesthetic and eloquent values prevalent at the time. On the other hand, there is one upper voice to the descending chromatic fourth that seems to have been chosen more regularly over time than others: the one producing a chain of 7–6 suspensions. And let that be precisely the version Mattei asks for in this verset.

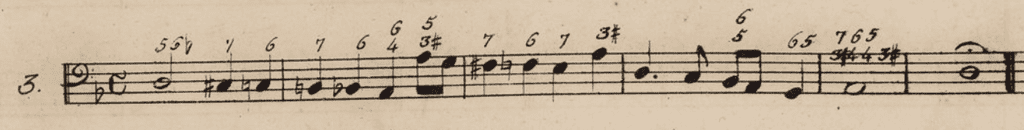

The chain of 7–6 suspensions is also a standard counterpoint to a simpler version of the descending chromatic fourth, namely a descending diatonic tetrachord.

The reason I mention this is that each of the chromatic semitones of the lament bass represents only one note —the flattened one— and supports only one harmony —a sixth chord.

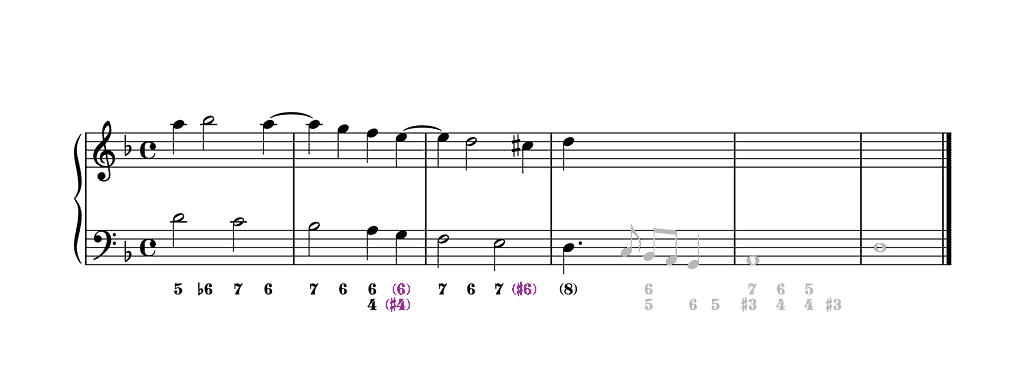

Although rare, versions can be found in which this upper voice is preserved, giving the bass its chromatic form:

In its omnipresent version, both the bass and the upper voice are embellished on both strong beats, the bass producing a raised scale step, the upper voice a suspension:

Note that in this case, the first suspension/seventh is prepared by changing the fifth into a sixth on beat 2 in bar 1 in the upper voice.

When the bass reaches A in the middle of bar 2, it leaps up an octave to begin a new, only partly chromatic descent, this time from a to d (via a). (The second descent contains only one chromatic semitone, f♯–f(♮).)

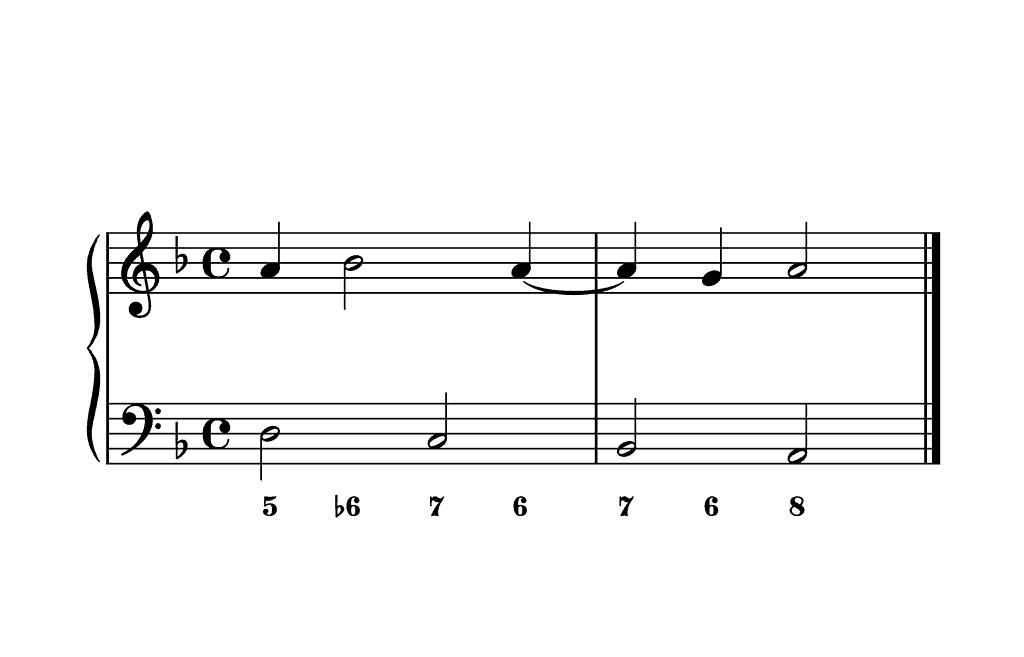

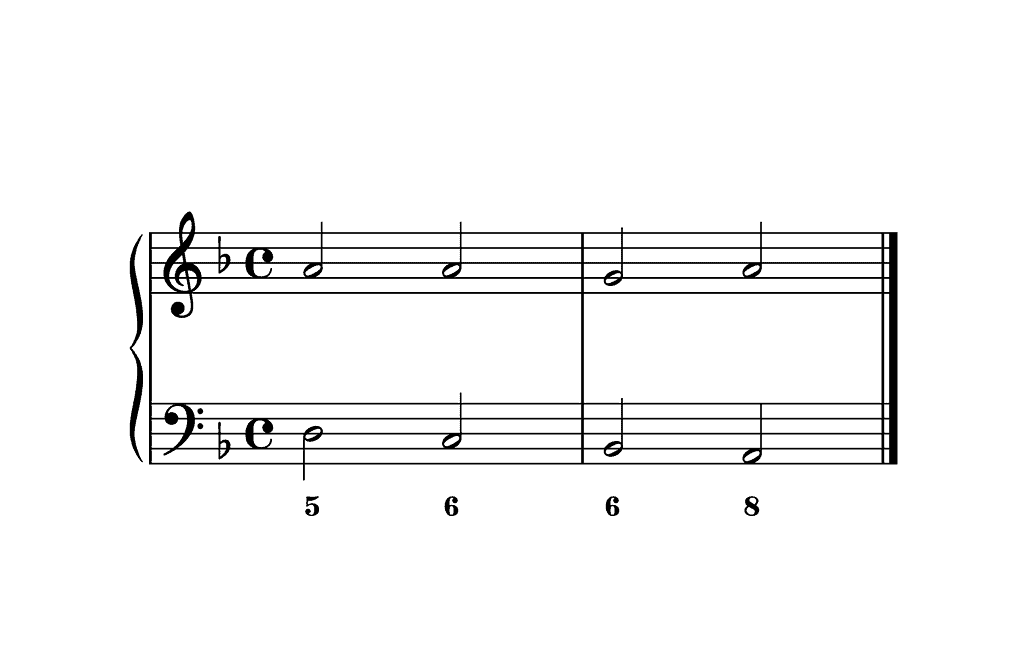

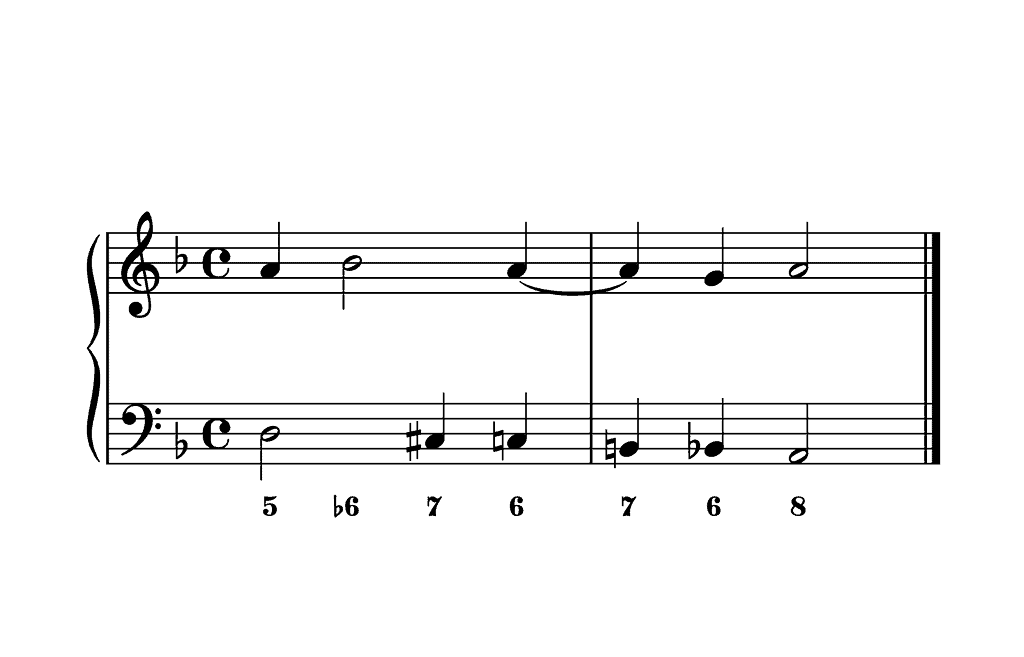

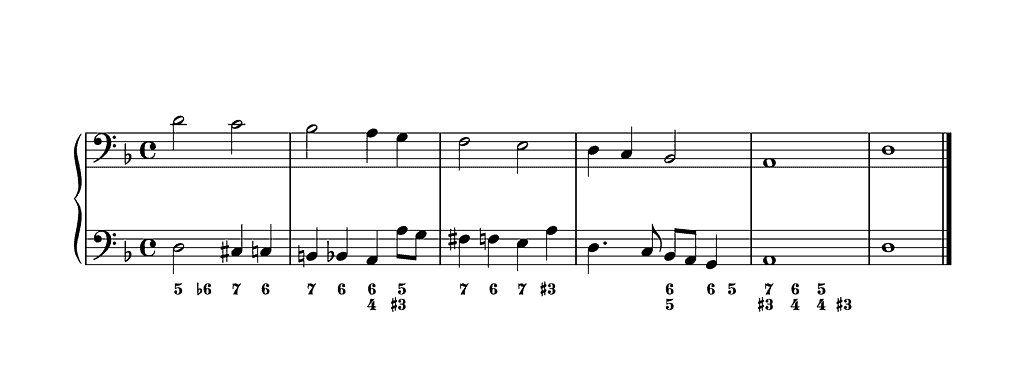

Translated into scale-step numerals, the start and end notes of both descents are ① and ⑤, and ⑤ and ①, respectively. So, both descents together represent an embellished, chromatic version of a complete descending scale of D minor set with a chain of 7–6 suspensions. (This suspension chain is temporarily abandoned in the middle of bar 2 due to the speeding-up of the bass.) And bars 4 and 5 are a third descent/continue the descent, embellishing a descending diatonic tetrachord from d to A (via G). Here you can see both a rudimentary, completely diatonic version and the embellished version as given by Mattei:

Notice how, thanks to the octave leap in bar 2b in Mattei’s version, the lament bass stands out more than if the descent had been completely stepwise.

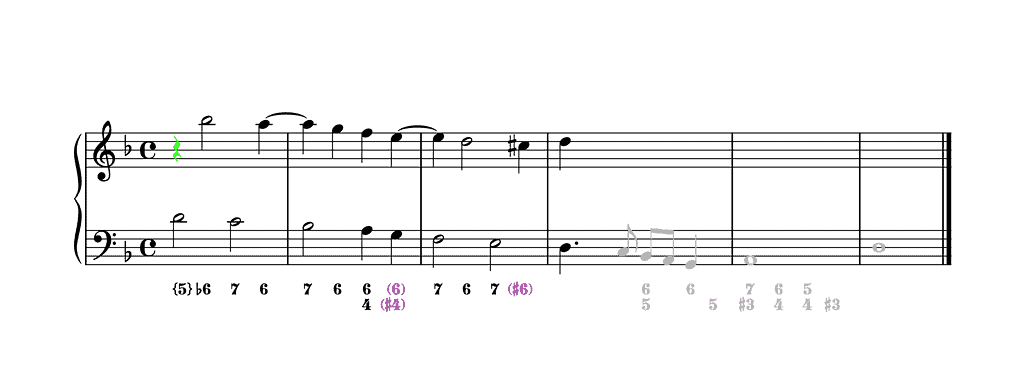

In the following example, I have realized the rudimentary version of the descending diatonic scale in a two-part setting, implying Mattei’s (top) thoroughbass figures:

In the following example, the first note in the top voice has been replaced by a rest, emphasizing the syncopations in the top voice and therefore the individuality of both voices somewhat more:

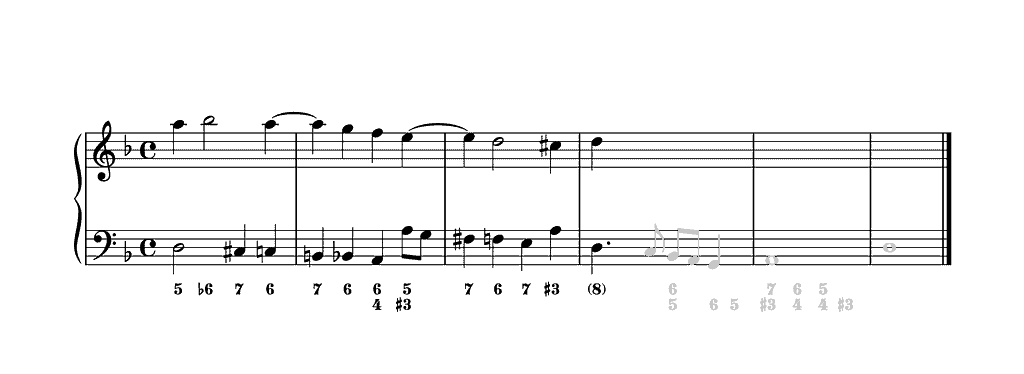

The next two examples combine the top voice of the two previous examples with Mattei’s actual bass:

In the next two examples, a middle voice —essentially in parallel thirds with the bass— has been added to obtain a three-part setting:

Note how the leading note descends stepwise in the middle voice in bar 2b–3a. This can be considered legitimate voice leading because at that point the middle voice produces a distinct motive in parallel thirds with the bass (indicated by dark green hooks). As a matter of fact, this voice leading is necessary to prepare the suspension of the seventh in the top voice on the downbeat of bar 3. Still, this voice leading is more suited for a middle voice than an outer voice. (See also below.)

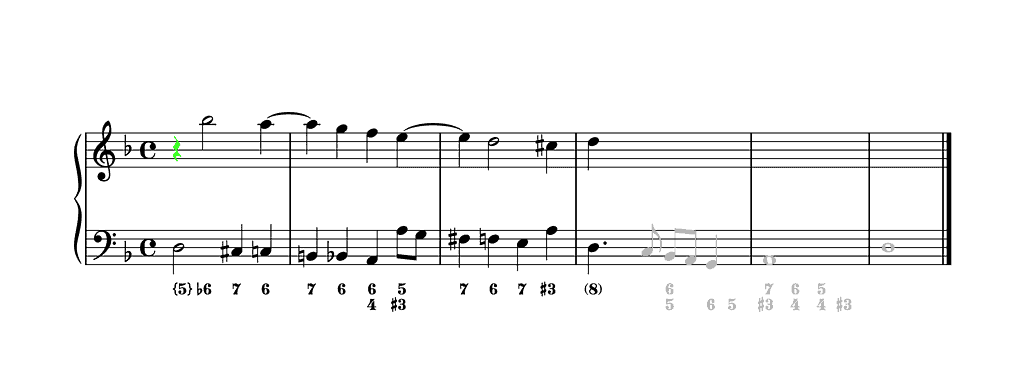

Just as Mattei opted for a chromatic version of the descending scale in the bass, one can also add chromaticism to the middle voice (bars 1b and 3b, indicated by dark green hooks):

One can also add chromaticism to the top voice in bar 2a, in which case the suspension/seventh is replaced by a major sixth:

I have indicated the chromatic descents starting with a half note —whether syncopated or not— with pink hooks. Note how the bass, joined by the middle voice in parallel thirds, and the top voice from bar 1 are engaged in a stretto at the distance of a quarter note. As a matter of fact, contrapuntists might argue that the bass and the middle voice are also engaged in a stretto, more particularly in a stretto sine pausa (without pause) at the tenth. Another stretto at the distance of a quarter note occurs between the alto and the top voice in bar 3.

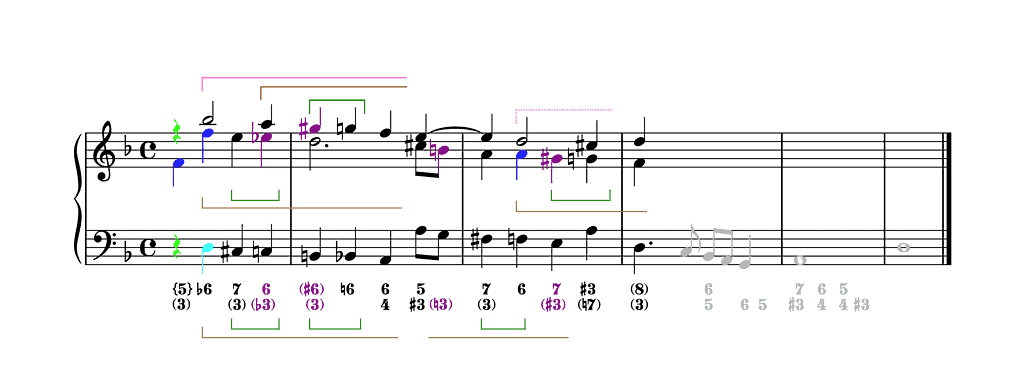

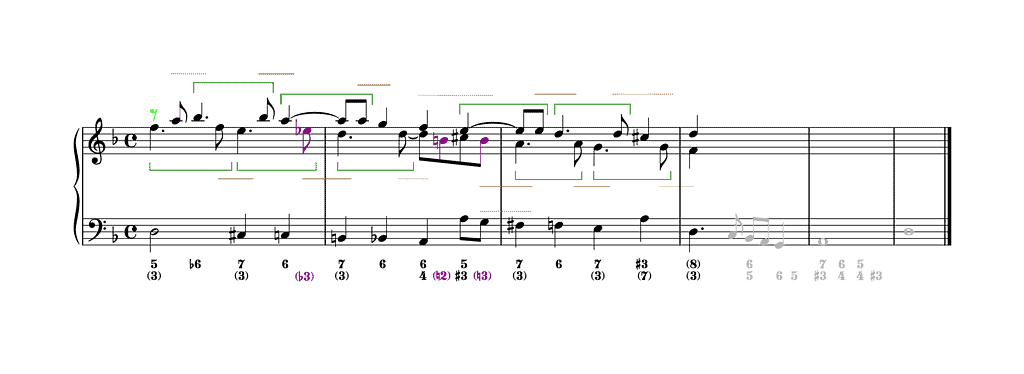

In the next example, I have modified the first half note d in the bass into a quarter-note rest followed by a quarter note d. As such, the chromatic descent consists of only quarter notes, starting on weak beat. With the same purpose, I have modified the half note a1 in the middle voice in bar 3a into two quarter notes a1. These modified chromatic descents are indicated by brown hooks. At the same, the chromatic descent starting with a half note (indicated by pink hooks) occurs at different spots in the first three bars as well.

Notice the different stretti.

If one wants to put forward more the chromatic descent starting on a weak beat with a quarter note, the following version is another step in that direction:

In this case, the first half note f2 in the middle voice is transformed into two quarter notes f1–f2. Thanks to this octave leap, the chromatic descent in the middle voice really starts on beat 2 (with a quarter note) instead of on beat 1 (with a half note).

An alternative start is shown here:

The octave leap doesn’t occur in the middle voice now —the initial quarter note f1 has been replaced by a quarter-note rest— but in the bass.

In the next version, the top voice starts only on the fourth quarter note of bar 1, ignoring the B♭. This version clearly favours the imitation of the chromatic descent starting with a weak quarter note.

And the next version goes as far as to suggest a fugal start to this versetto, although the third entry is irregular (it doesn’t/cannot start on d2 but on e2 and is diatonic instead of chromatic):

Note that

- the parallel six-four chords on beats 2 and 3 of bar 2 are only allowed in minor since the vertical fourth of the first six-four chord is augmented

- in any of the versions above, there is room for the insertion of at least one more chromatic semitone, in the top voice on beat 3 of bar 2:

Note how the insertion of an extra chromatic semitone on beat 3 of bar 2 prolongs the chromatic descent with two notes.

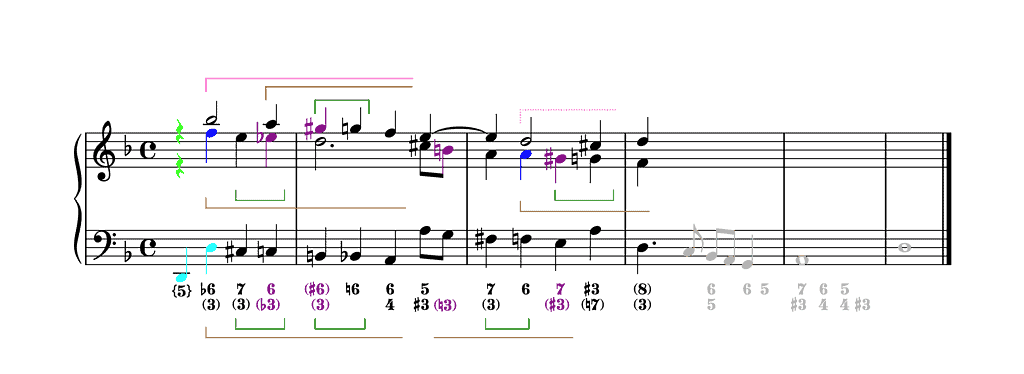

And there is room for even more chromaticism. Have a look at the following example:

As you can see, the bass in bar 2b has been embellished, introducing the octave leap an eighth note earlier and inserting g♯ in between a and g. As such, another chromatic descent starting on A occurs, although its first three notes are eighth notes instead of quarter notes. This chromatic descent is accompanied with another one in the middle voice, starting on c(♮)2, which produces a stretto sine pausa in the tenth.

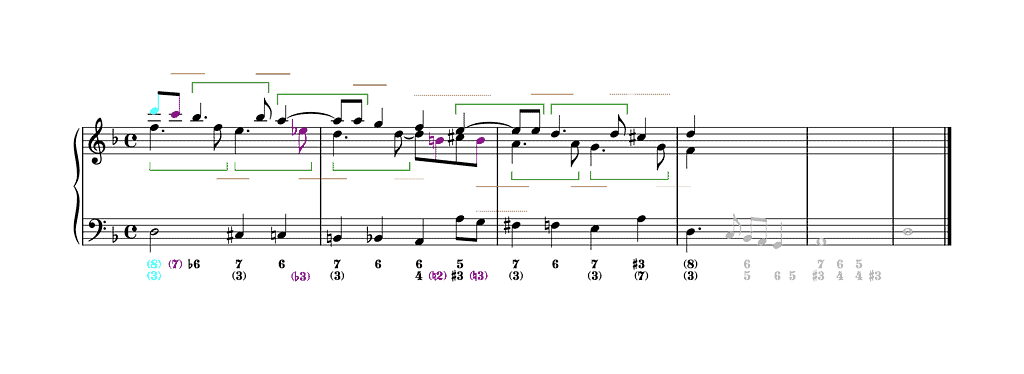

Let’s have another look at the first descending chromatic fourth in the bass. Until now, the weak beats have always been set with light sixth chords, mostly as the resolution of the suspension/seventh on the preceding strong beats. (As for the sixth chord on beat 2 of bar 1, it ornaments the initial triad of this versetto.) In other words, these sixth chords are not distinctive but linked to the chord on the preceding, strong beat. Alternatively, the weak beats can be set with vertical tritones, which create distinctive chords and promote the metrical status of the weak beats:

In the example above, the presence of vertical tritones in the top voice on beats 2 and 4 of bar 1 results in a (potential) temporary shift of key: g♯2 above d on beat 2 would allow a shift to A minor (but proves to be only a chromatic alteration in D minor), f♯2 above c(♮) on beat 4 announces G minor (which is confirmed only partially due to the B(♮) in the bass on the next downbeat). In this case, both vertical tritones are accompanied with vertical minor thirds in the middle voice. While beat 2 of bar 2 is also set with a vertical tritone, the middle voice produces a vertical major third, which creates a chord that clearly belongs to D minor.

In the next example, the middle voice produces a vertical minor third also on beat 2 of bar 2, creating a brief key shift to F major. (Although d♭1 obviously seems to suggest F minor, this key is too remote in the context of the main key D minor. In this case, d♭1 works as a chromatically lowered sixth scale step (♭➏) in F major, which is known today as a hermaphrodite note.

The same realization, with hermaphrodite note, has been applied to beats 2 and 3 of bar 3, where the temporary key is C major.

Note the two ascending chromatic semitones in the example above in the middle voice in bar 2b and in the top voice in bar 3b (indicated by brown hooks).

While in the two previous examples, the vertical tritones were always combined with vertical thirds, in the next two examples they are combined with vertical seconds, which creates a syncopation chain in the middle voice:

Note how

- the syncopated half note g1 in the middle voice in bar 3 requires beat 4 to be marked, in this case by repeating the same note (the part of the syncopation that occurs on the strong beat can never be longer than the part that occurs on the preceding weak beat)

- the middle voice in the second example starts on beat 2 instead of on beat 1, favouring the perception of imitation/stretto with the bass

- the upper voices both start in a dissonant context, which is unusual yet possible due to the chromatic and dissonant character of the setting.

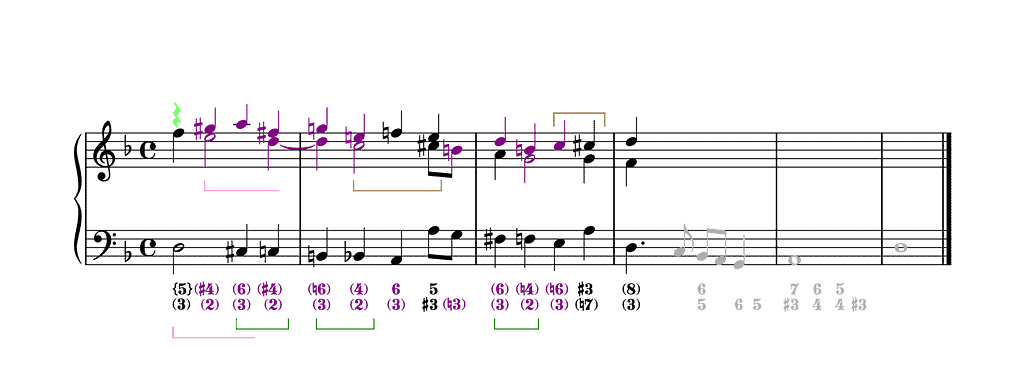

The next version focusses on contrary motion between the bass and the top voice. While the bass descends chromatically from d to A (downward from ① to ⑤) from beat 1 of bar 1 to beat 3 of bar 2, the top voice rises from d2 to a2 (upward from ➊ to ➎), including a chromatic snippet from f♯2 to a2 (from ♯➌ to ➎).

Note

- the vertical tritone on beat 4 of bar 1 between the bass and the upper voice

- the vertical tritone on beat 2 of bar 2 between the middle voice and the upper voice

- the augmented sixth on beat 2 of bar 2 between the bass and the upper voice.

John Rice has labelled this setting of the chromatically descending tetrachord in the bass a Morte. For more information see my essay Chromatic Moti del Basso.

Another contrary motion between the bass and the top voice occurs from beat 4 of bar 2 to beat 1 of bar 4: the bass descends from a to d while the top voice ascends from a1 to d2.

Note that, to make the transition between both phrases smoother/freer, I replaced the six-four chord on beat 3 of bar 2 with a triad.

Before we move on to bar 4, I want to discuss some possibilities for embellishing bars 1–3. In the next example, I use the simple technique of embellishing each half note by splitting it into a dotted quarter note followed by an eighth note repeating the dotted quarter note. (In the middle voice in bar 1b, that eighth note is a chromatically lowered version of the preceding dotted quarter note.)

Notice how this technique creates complementary rhythm in eighth notes between the upper voices as the dotted rhythms in the upper voice begin on a strong beat and those in the upper voice on a weak beat (per arsin et thesin).

Because the upper voices alternate rhythmically on the weak part of a beat, one can hear upbeat motives (indicated by brown strokes) simultaneously with on-beat motives (indicated by dark green hooks).

In the following version, the weak eighth note on beat 1 of bar 1 in the upper voice is changed from a2 in c3, changing the rising upbeat motive into a descending one, consistent with the other ones of this fragment:

Notice that the upper voice doesn’t start with an eighth-note rest but an eighth note d3; it is better to start a part/phrase with a consonance than with a dissonance.

While the half notes in the two preceding versions are embellished with repeated notes, one can also opt for escape notes in the middle voice and incomplete neighbour notes in the upper voice:

Note that

- the upper voice starts with a quarter-note rest, so that the fifth of the opening triad is not explicit

- I didn’t indicate the upbeat motives anymore

- the dark green hooks indicate the escape-note motives

- the pink hooks indicate the incomplete neighbour-note motives.

Notice further that

- The first two incomplete neighbour notes (in the upper voice) are chromatically raised (g♯2 and f♯2). If diatonic versions of these occurred (g(♮)2 and f(♮)2), they would form vertical diminished fifths with the bass, in which case g(♮)2 and f(♮)2 would rather have to descend. (The third incomplete neighbour note is also chromatically raised (c♯2), but this alteration is self-evident because c♯2 is the leading note.)

- The last escape note (at the end of bar 3 in the middle voice) is of the consonant type. A consonant escape note interrupts the usual descending motion of a dissonance (here a seventh) to its resolution by first rising a step (here to the octave).

While a three-part setting with one upper voice producing the chain of 7–6 suspensions and the other parallel thirds with the bass is in itself invertible, the moment when this moto del basso is interrupted in bar 2 makes this inverted voice leading slightly less favourable:

After all, the ➐–➏–➎ snippet occurs in the top voice, making the descending leading note audibly more prominent.

The next example illustrates how to start with inverted upper voices and switch to the combination with the 7–6 suspensions in the top voice at the end of bar 2, solving the issue of the descending ➐:

Notice how

- The quarter note c♯2 on beat 4 of bar 2 is transformed into two eighth notes c♯2–e2.

- The second eighth note e2 on beat 4 of bar 2 coincides with g in the bass, forming a vertical sixth and thus nicely making up for the doubled E and the absence of C♯.

- The preparation of the suspension on beat 1 of bar 3 lasts only an eighth note, so the actual rhythmic value of the suspension shouldn’t exceed an eighth note. Still, to preserve the suspension throughout the beat, e2 is simply repeated on the weak part of the beat.

- The repeated eighth note on beat 1 of bar 3 in the upper voice becomes an embellishing element that is worked out throughout bar 3 (notice the light blue notes).

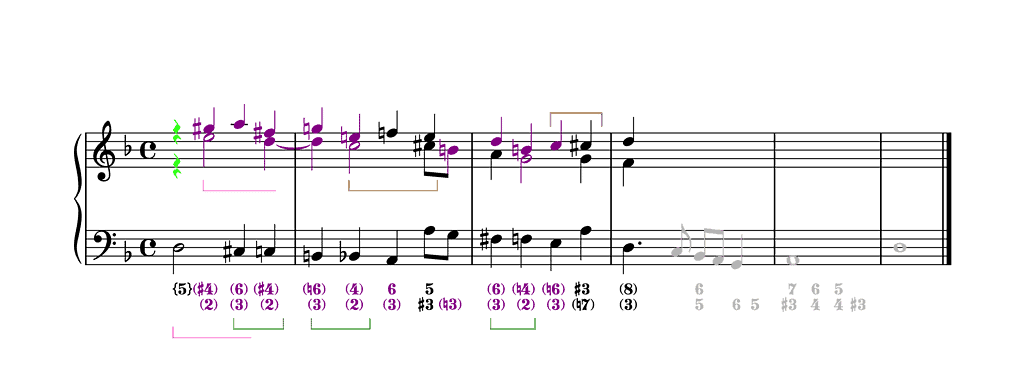

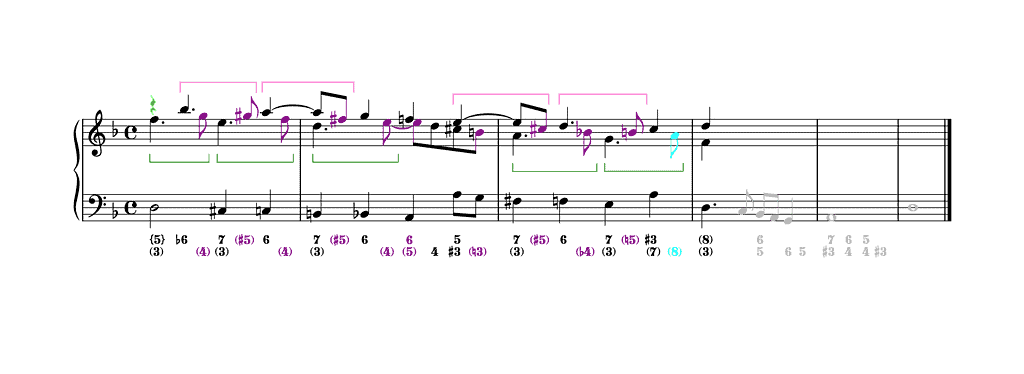

Now let’s move on to bar 4. Its bass is based on the motive of beat 4 of bar 2 and beat 1 of bar 3— a stepwise descending third, where it occurs explicitly in the bass and implicitly in the middle voice (indicated by dark green hooks). In the bass of bar 4, this motive occurs twice in succession, the end note of the first also being the beginning note of the second. Its first occurrence starts on the downbeat, with the first note being thrice as long, so that the second and third notes have a similar metrical organization to those of the motive during the transition from bar 2 to 3. As for its second occurrence, it consists of three notes with the same rhythmic values as the motive during the transition from bar 2 to 3, but is presented per arsin et thesin:

Notice how Mattei’s thoroughbass figures

- on beat 4 of bar 4 and beat 1 of bar 5 indicate an imitation of the bass motive in stretto where the middle voice presents this motive in its regular metrical construction one quarter note later (indicated by a dark green hook in the middle voice).

- imply that the g1 in bar 4b in the upper voice stays put until the downbeat of bar 5, resulting in a doubled G on beat 4 of bar 4, notwithstanding that the G in the bass is set as a sixth chord. (This voice-leading takes precedence over the rule that, when realizing a sixth chord in a three-part setting, all three chord factors must be present vertically, with each one appearing in a different part.)

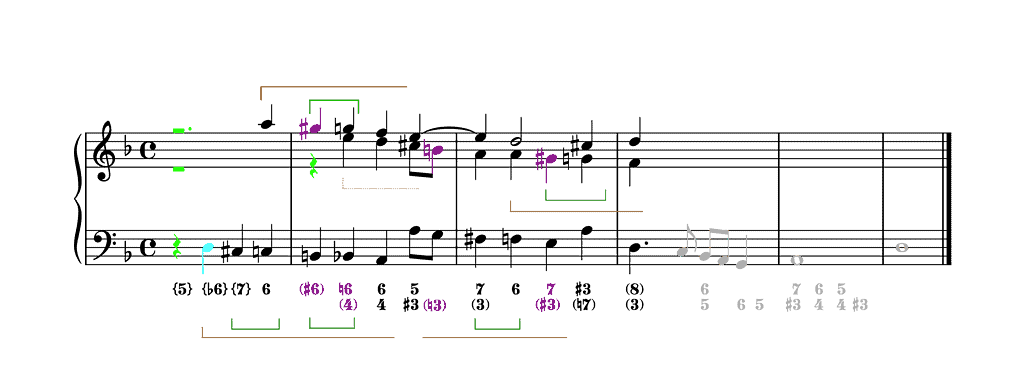

The following example proposes a version with inverted upper voices from beat 2 of bar 4:

The latter version, in which the upper voices leap a third up from beat 1 to 2 of bar 4, offers the possibility for two embellishments that heighten the contrapuntal coherence of this bar:

The rising leap in each of the upper voices from beat 1 to 2 is filled in melodically, resulting in stepwise rising thirds (indicated by brown hooks), an inverted version per arsin et thesin of the descending motive in the bass of beat 4 of bar 2 and beat 1 of bar 3.

The middle voice in the following version anticipates the four-note bass motive of a descending fourth c–G two octaves higher, making it into a figura suspirans. In turn, the upper voice imitates the same motive at the fourth. These motives are indicated by pink hooks. The result is a three-part stretto where the middle and the top voices present the suspirans in its regular metrical construction, the bass per arsin et thesin.

Like the example before the previous one, the following one also presents ascending, on-beat melodic thirds in the upper voices in bar 4a. The upper voice, however, instead of prolonging the f2 until beat 3, rises chromatically on the second half of beat 2 to rise further to g2 on beat 3, thereby ignoring the indicated 6/5 sonority on that beat. Yet the F that is supposed to be played on beat 3 (indicated by “5” in Mattei’s thoroughbass figures) does appear during that beat, albeit one eighth note later (see the dark blue note and thoroughbass figure). I call this contrapuntal technique horizontalizing the dissonance.

Note that the sixth chord on beat 3 of bar 4 is incomplete; it contains two occurrences of the sixth and no third. Although this is irregular, it is acceptable here due to horizontal logic.

The three successive vertical sixths in the outer voices in bar 4b of the previous example permit a setting in which each sixth represents two of the three voices of an actual sixth chord, to which the third is added in the middle voice to complete the sixth chord:

Notice

- the speeding up of the harmonic rhythm at that point

- that I have set the vertical tritone c–f♯2 in the outer voices on the fourth eighth note of bar 4 with a minor third in the middle voice, creating an ♯4/♭3 sonority

- that this ♯4/♭3 sonority results in the addition of another figura suspirans per arsin et thesin to the texture, an imitation sine pausa of the same motive in the bass (indicated by pink hooks)

- that the seventh on beat 1 of bar 5 in the middle voice cannot be prepared: b♭1 (♭➏) must first descend stepwise to a1 (➎) before descending further to g1 (➍), with the latter becoming a passing note instead of a suspension.

Another possible variant is to transform the vertical major sixth g–e2 in the outer voices on beat 4 of that bar into a minor sixth g–e♭2, creating a Neapolitan sixth chord:

Like the two previous examples, the last two examples of this essay are identical, apart from the absence or presence of a Neapolitan sixth chord on beat 4 of bar 4. They explore a descending melodic fifth as the main motive in bar 4 (indicated by pink hooks). (In fact, each descending melodic fifth is the result of two overlapping descending melodic thirds (indicated by dark green hooks).) In both, an F♯ occurs in the middle voice on beat 2 instead of on the second eighth note of that beat, creating a vertical diminished fourth with the third note of the descending melodic fifth in the upper voice (b♭1).

Note that the sixth chord on beat 3 of bar 4 is again incomplete with two occurrences of the sixth and no third, also a result of the horizontal quality of the upper voices.

For possibilities on how to realize the final cadence see my essay Mattei, Verset 2 in C Major.

Select Bibliography

Caplin, William E. Topics and Formal Functions: The Case of the Lament, in: The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, ed. Danuta Mirka (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 415–452.

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207–229.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Rice, John A. The Morte: A Galant Voice-Leading Schema As Enblem of Lament and Compositional Building-Block, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 12/2 (2015), 157–181.

Williams, Peter. The Chromatic Fourth during Four Centuries of Music (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997).