This essay deals with the second verset (i.e. short partimento) in C major by Stanislao Mattei (1750–1825).

The versets by Mattei are a remarkable collection of pedagogical pieces intended to be realized in three parts at the keyboard with great concern for contrapuntal quality. Moreover, instead of focusing on just one realization, students had to explore as many options as possible.

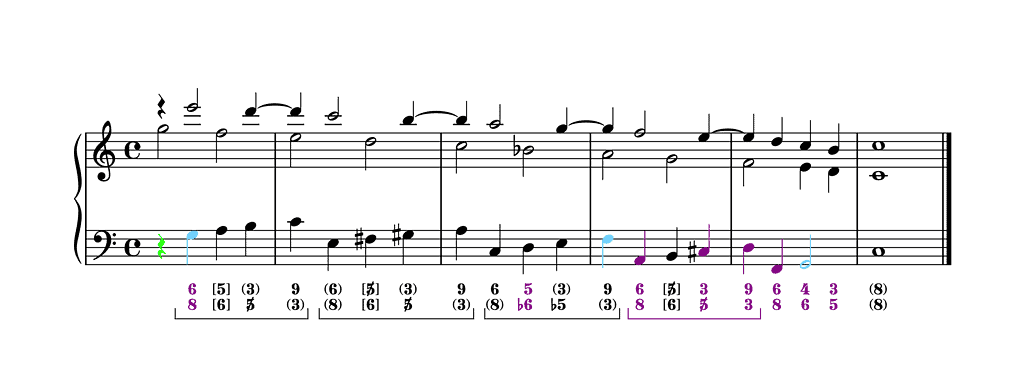

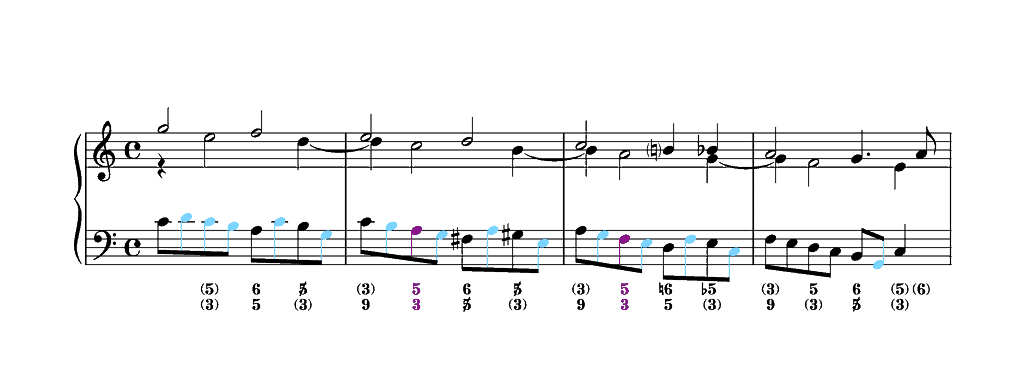

In the musical examples of this essay, I am using the following colour code:

- Red: questionable voice leading

- Purple: alternative version in the bass and/or in relation to the thoroughbass figures

- Light green: a rest replaces a note (also in the bass)

- Light blue: diminutions (also in the bass)

- Dark blue: something that is worthwhile looking at.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in an upper voice (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♯④ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ⑤

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Note further that

- ‘Bar 1a’ refers to the first half of bar 1, ‘bar 1b’ to its second half.

- I am using the Helmholtz pitch notation for naming musical notes. When I refer to notes without a specific register/octave, I use upper-case letters.

- In the musical examples throughout this essay, the thoroughbass figures as they appear in the 1824 edition are modified and made explicit to reflect exactly the voice leading and relative position of the upper voices.

- Thoroughbass figures between parentheses are editorial, those between brackets mean that they are ordered differently than those in the 1824 edition.

While I have written out all the musical examples in this essay, I strongly recommend reading only the thoroughbass figures as you play them through, only looking at the realization when in doubt. That way, you ‘think counterpoint’ instead of ‘notes’.

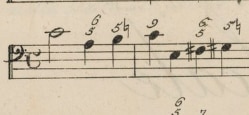

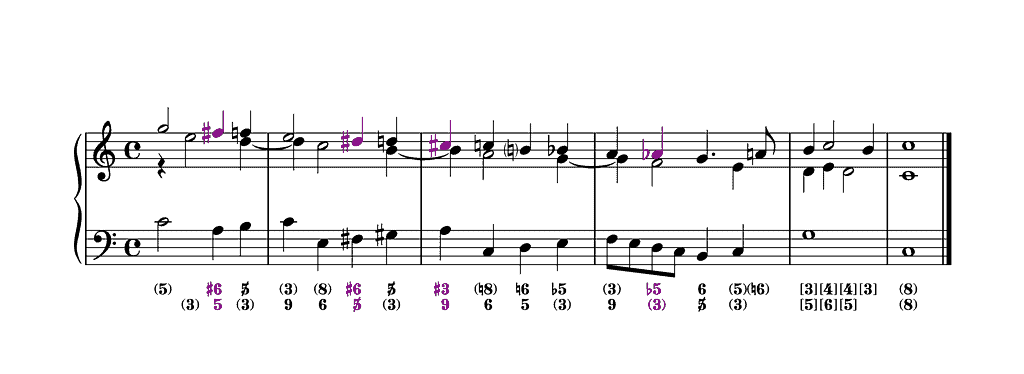

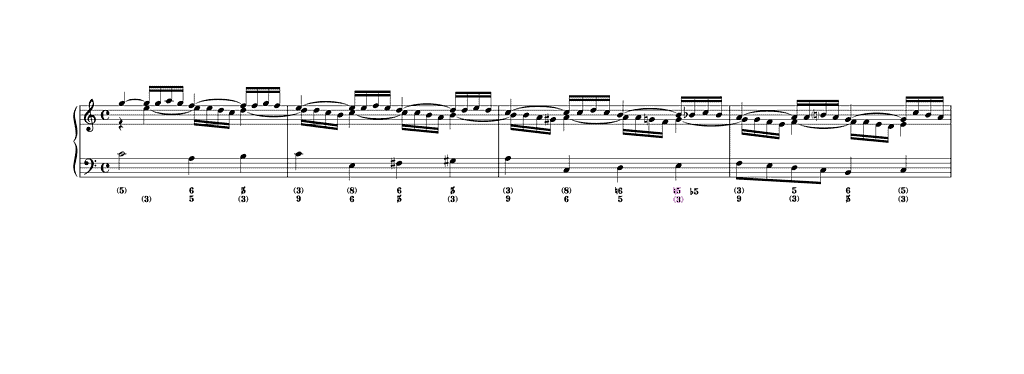

This is the unrealized second verset in C major of Mattei:

This verset is based on a descending pattern that Vasili Byros has labelled a Fonte-Romanesca, “as it results from a combination of features belonging to the Romanesca and the Fonte” (Byros (2017), p. 77). What the Fonte-Romanesca has in common with the Romanesca is that each subsequent segment is a third lower. (Note that this type of sequence is rather exceptional. Indeed, most moti del basso are progressions in which each subsequent segment is a second lower or higher.) What the Fonte-Romanesca has in common with the Fonte is that each segment is a mild ⑦–① cadence or clausula cantizans (or, as Gjerdingen calls it, Comma). Typical of the Fonte-Romanesca, however, is that each of these cadences is usually extended into a ⑥–⑦–① snippet, which Gjerdingen calls a Long Comma.

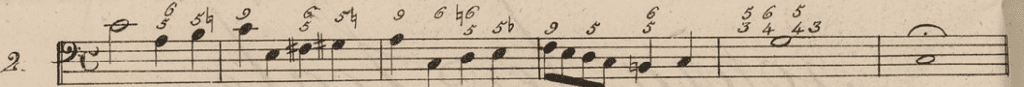

In the example below, I have normalized Mattei’s bass to make this schema as clear as possible. (Mattei’s version includes some variation and modification of the pattern.)

Indicated by the hooks below the bass line, you can see that each segment consists of a ⑤–⑥–⑦–① snippet in C major, A minor, F major and D minor, successively.

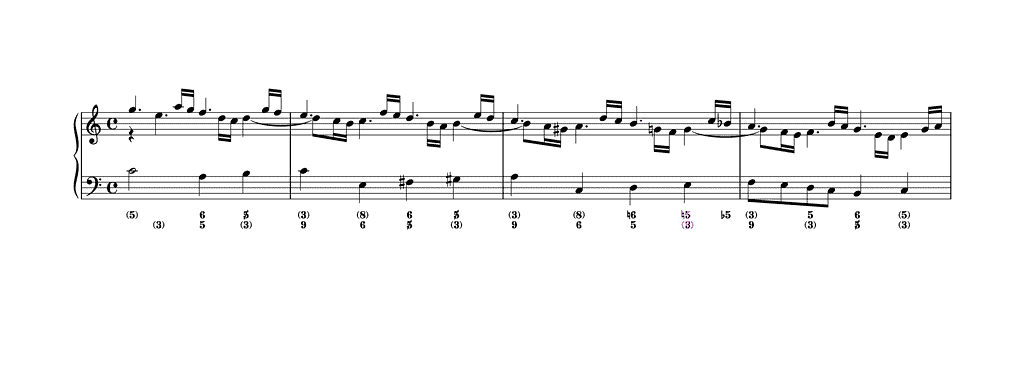

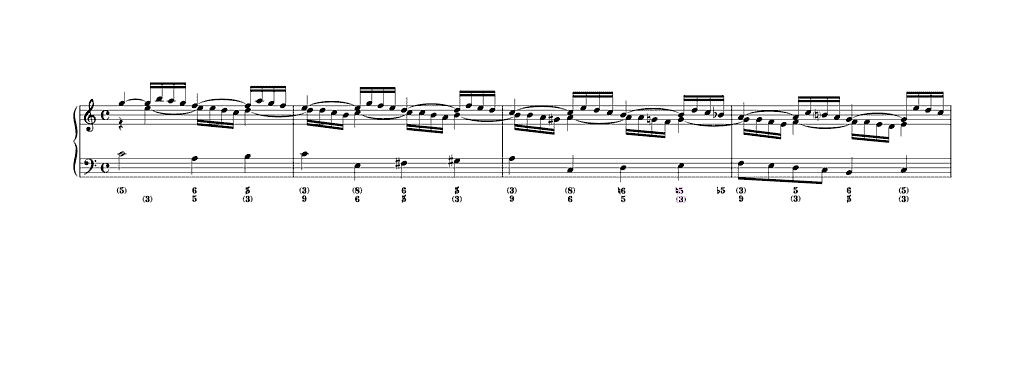

The next example shows a typical setting of this standardized version of the Fonte-Romanesca:

As is the case with the Romanesca, the upper voices of the Fonte-Romanesca both descend stepwise. And as with the Romanesca including a suspension chain, one upper voice is metrically regular while the other consists exclusively of syncopations/suspensions. In other words, each segment of a Fonte-Romanesca consists of metrically regular ⑤–④–③ snippet in one voice (here in the top voice) and a syncopated ③–②(–①) snippet in the other (here in the middle voice).

Notice how this voice leading results in the marking of two successive vertical sixths on the first two bass notes of each snippet and two successive vertical thirds on the last two bast notes of each snippet, the first of each vertical sixth and third between the bass and the middle voice, the second between the bass and the top voice.

As the following example illustrates, the top voices are written in invertible counterpoint and can therefore be swapped:

Let’s reassess Mattei’s bass now and see how and where he varied this standardized form.

There are several differences:

- In bar 1a, Mattei writes a half note c1 in the bass, ignoring a possible g on beat 2, which he could still have written if he had made the c1 on the downbeat into a quarter note. With the half note c1, however, this versetto arguably begins a little more solidly.

- In bar 3b, he opts for a chromatic variation of the local ➍–➌ snippet (in F major) in one of the upper voices, transforming the half note ➍ (B♭) into two quarter notes ♯➍–➍ (B♮–B♭).

- In bar 4a, instead of continuing the sequence and writing again a descending sixth in quarter notes (f–A), Mattei varies the line by writing a stepwise descent in eighth notes to arrive at the B on beat 3 of bar 4. (This is in fact an embellishment of two quarter notes f and d.) As such, the sonority on beat 2 is a minor triad on d instead of a sixth chord on A.

- In bar 4, the music doesn’t go to D minor but to C major. The last quarter note in the bass 4 is not c♯, which would lead to d as in the standardized versions above, but c(♮).

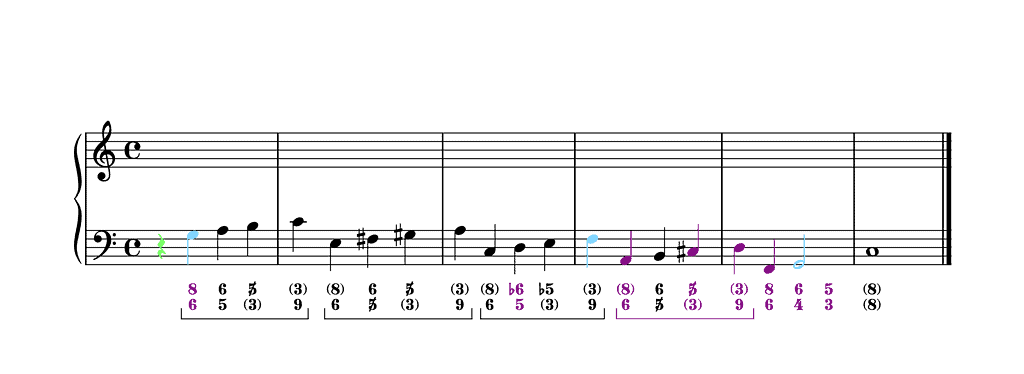

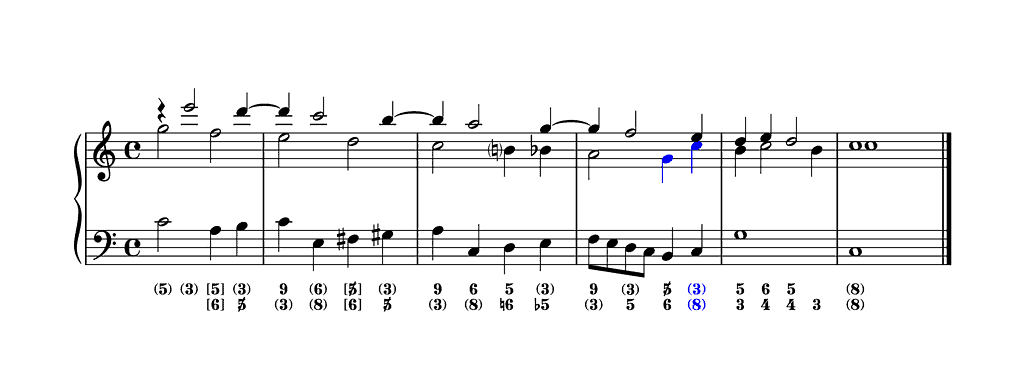

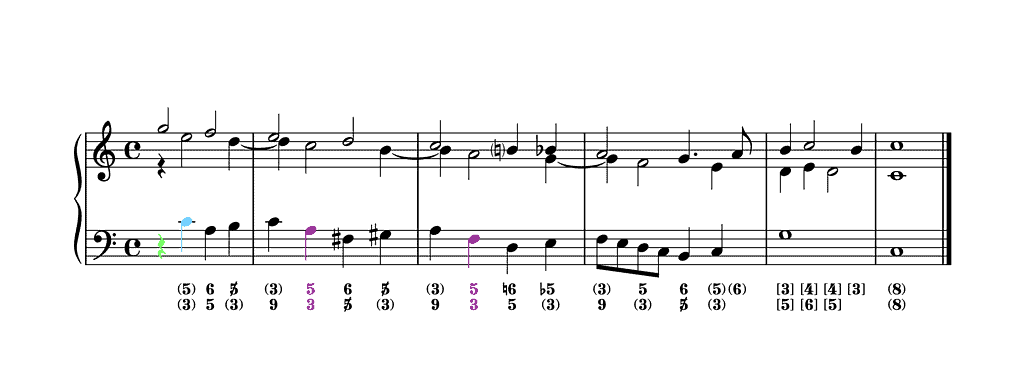

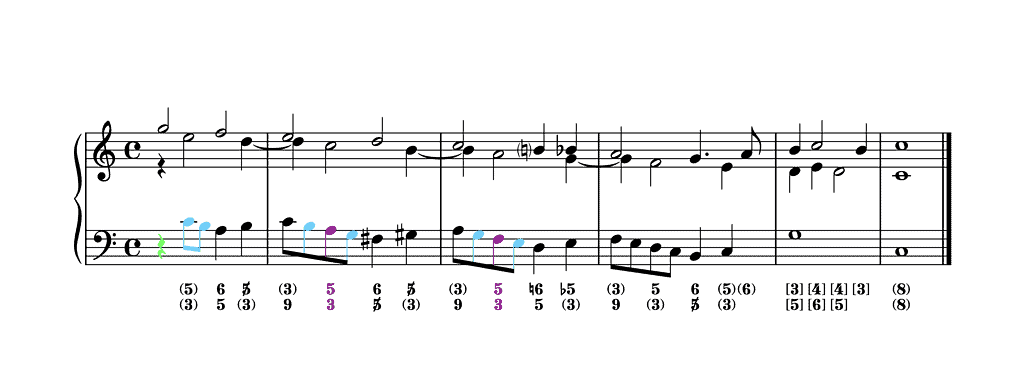

The standardized voice leading of the upper voices can be preserved entirely during the Fonte-Romanesca in Mattei’s version. The following two examples illustrate this voice leading in the two relative positions of the upper voices:

Note that I have inserted a passing note a1 in the top and middle voice, respectively, to smoothen the melodic progression from beat 4 of bar 4 (g1) to beat 1 of bar 5 (the leading note b1). If the leading note on beat 1 of bar 5 occurs in the middle voice, the g1 on beat 3 of bar 4 can also be followed by a quarter c2 on beat 4, on option that isn’t available if it occurred in the top voice because of the direct octave that would appear. (Still, the version with a quarter note c2 on beat 4 of bar 4 doesn’t result in the best melodic version of that part.)

Note that if the c2 occurs in the top voice as the final eighth note of bar 4, following a dotted quarter note g1, the issue of a direct octave is no longer there:

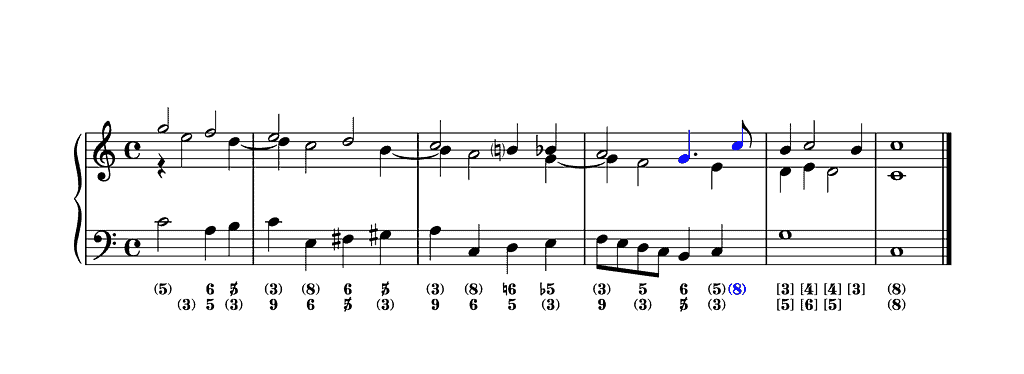

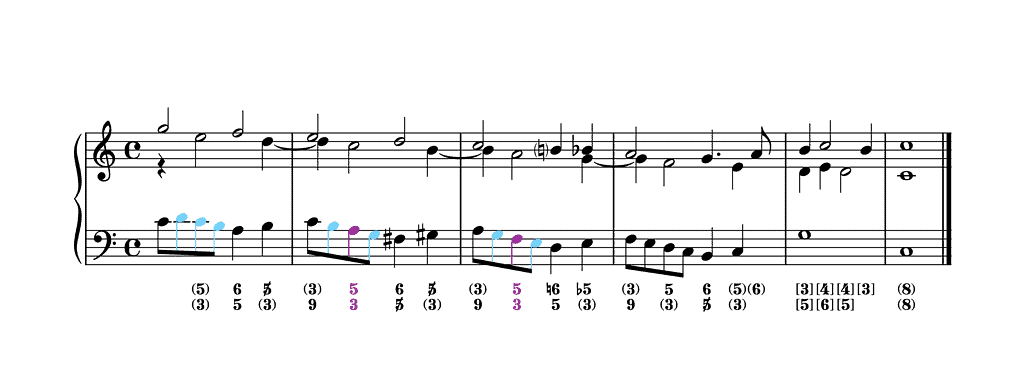

It is also a good idea to play a fully regular version of the Fonte-Romanesca in the upper voices above Mattei’s bass. This makes one fully aware of the chromatic variation in bar 3b afterwards. (To limit the number of musical examples, I will give examples in one position only from now on. However, do make sure to play them in both positions.)

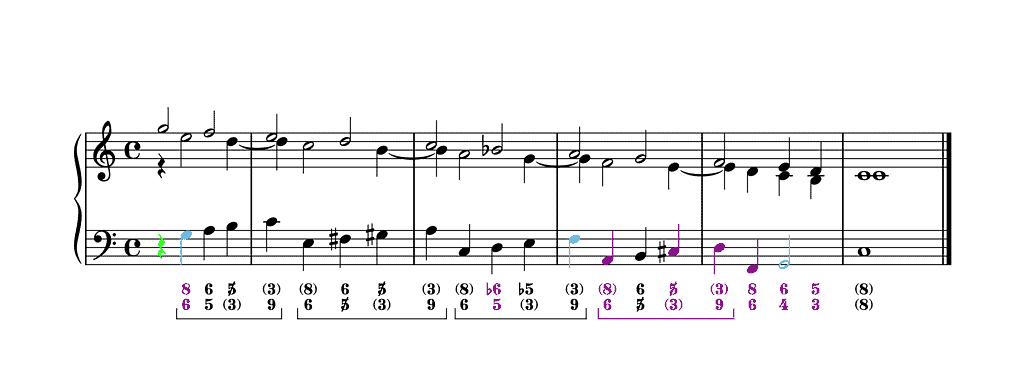

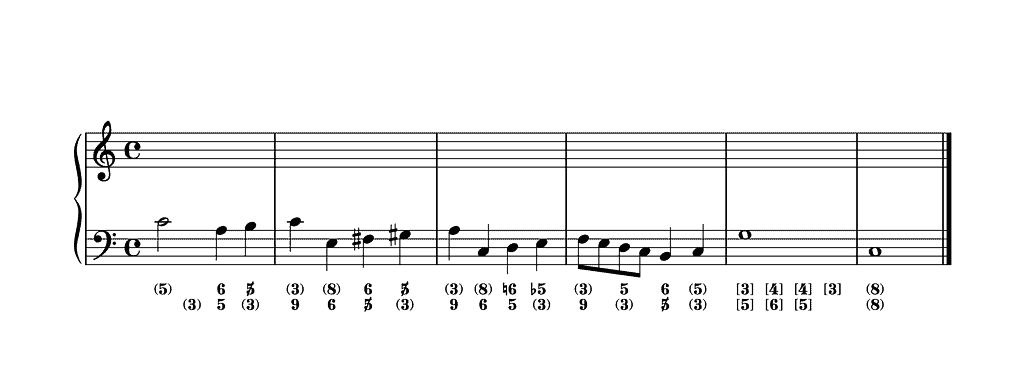

Another useful and important exercise is to apply the chromatic variation of bar 3b to all the segments of the Fonte-Romanesca, including bars 1b and 2b:

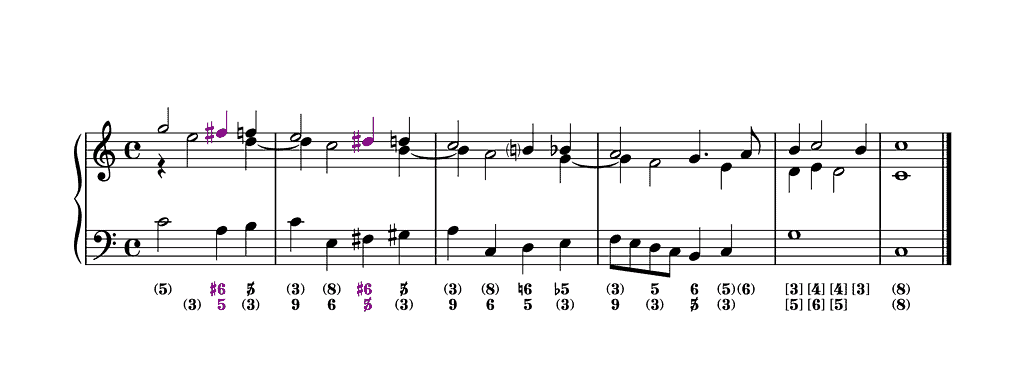

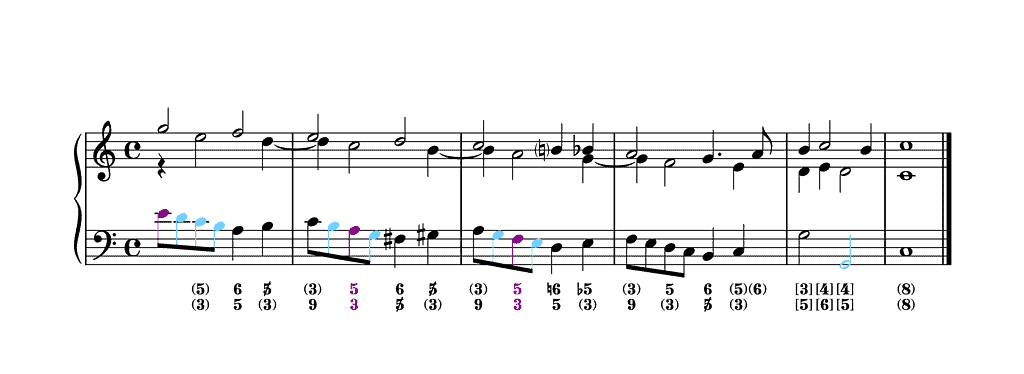

There is the possibility to insert another chromatic snippet in the top voice in bar 4a, changing the half note a1 into two quarter notes a1–a♭1. That a♭1 is ♭➏ in C major, a scale step that Robert Gjerdingen calls a hermaphrodite note after Joseph Riepel (1709–1782) (Gjerdingen: 2007, p. 67).

(Riepel considers a major key to be masculine and minor key to be feminine. Therefore, if a note belonging to the minor scale occurs in a major key, as is the case with ♭➏, the musical context is, according to him, hermaphrodite.)

And there is the possibility to insert yet another chromatic snippet in the top voice. The half note c2 in bar 3a can be transformed into two quarter notes c♯2–c2. As such, the descending scale from g2 to g1 is entirely chromatic.

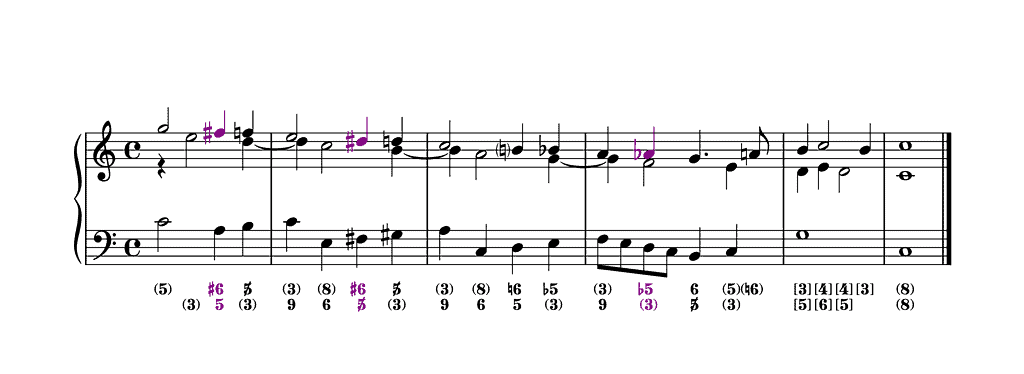

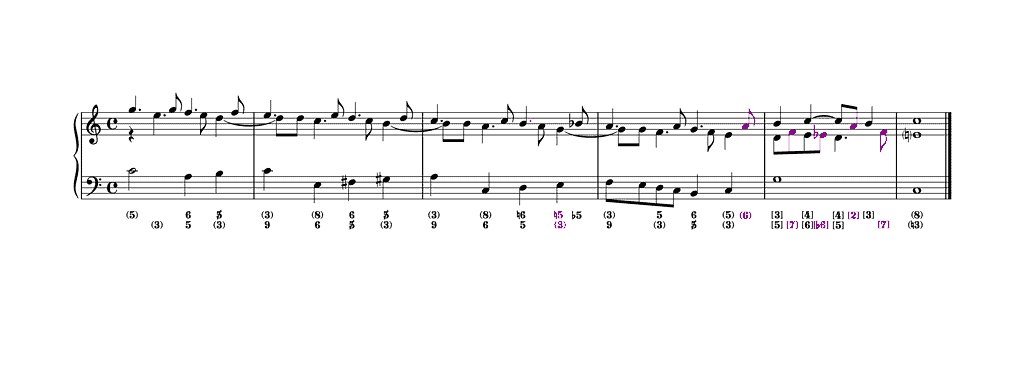

Let’s return to the version suggested by Mattei’s thoroughbass figures. If you want a version with running eighth notes (from the second beat of bar 1), one technique to achieve this is by transforming each regular and syncopated half note in the upper voices into a dotted quarter note followed by an eight note that repeats the preceding dotted quarter note:

The only exception occurs in the top voice in bar 3b, which contains the chromatic snippet. As you can see, b♭1 is postponed by one eighth note, b(♮)1 sounding on beat 4.

During the cadenza doppia in bar 5, note the syncopated f1 in the middle voice, which aims to preserve the running eighth notes by delaying the e1. (For more information on the cadenza doppia see my essay Cadences: The Basics.)

One could also choose to keep the e1 on beat 2, but transform it into an eighth note and have it followed by an eighth note e♭1, a reference to the chromatic snippet of bar 3b:

(One might call this e♭1 a hermaphrodite note as well.)

Another possibility to embellish the 6/4 on beat 2 of bar 5 is to delay the 4, which creates a 6/5 on that beat. In this case, the 5 needs preparation. This voice leading may or may not include the chromatic passing note e♭1.

Of course, many more settings of the cadenza doppia in eighth notes are possible.

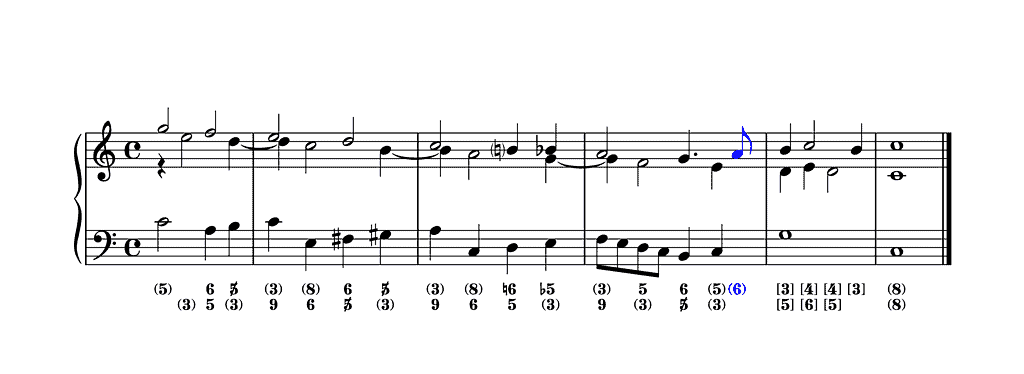

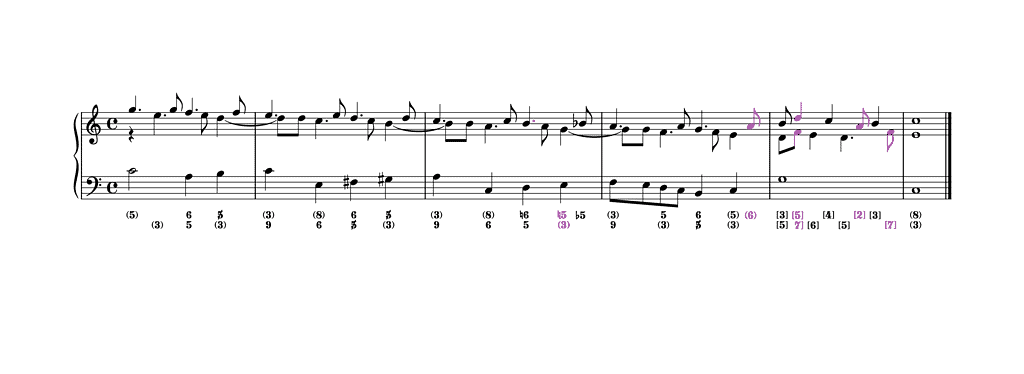

Let us now go back to the Fonte-Romanesca. The versions with running eighth notes can be further embellished, introducing sixteenths. In the version below, each repeated eighth note is transformed into two sixteenths, resulting in neighbour-note motives.

In the following example, every dotted quarter note is transformed into a quarter note tied to a sixteenth and a sixteenth repeating the previous note, a version resulting in running sixteenths:

Note that the top voice produces neighbour-note motives and the middle voice suspirans motives. (For more information on the suspirans see my essay Mattei, Verset 1 in C Major.)

In the following example, however, both upper voices produce suspirans motives:

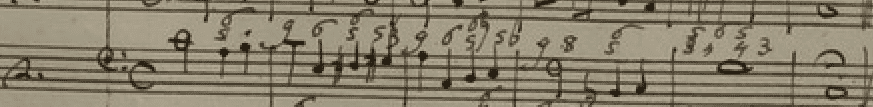

As I explain in my general essay on Mattei’s 100 versetti, not only the upper voices but also the basses of partimenti (and versetti) were varied and embellished, with special emphasis on making the contrapuntal fabric as beautiful as possible. As a matter of fact, Mattei himself changed bar 4a when he prepared the 1824 edition. In the 1788 autograph, he wrote a half note f instead of the four eighth notes f–e–d–c:

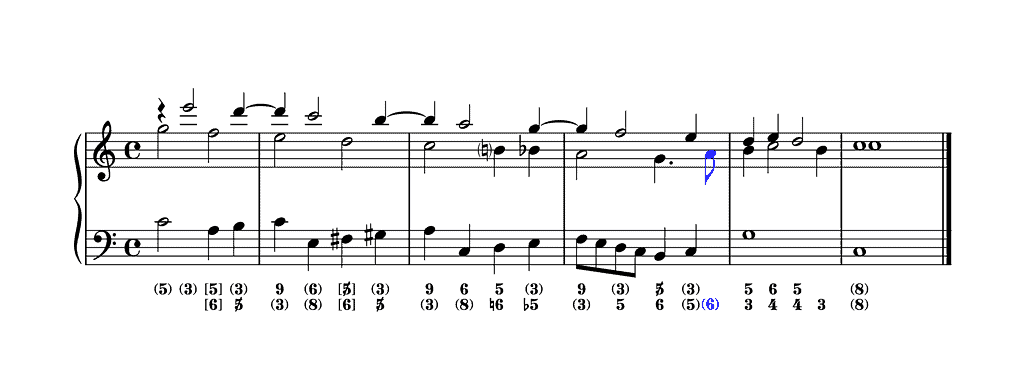

A common variant of the ⑤–⑥–⑦–① bass progression of each segment of the Fonte-Romanesca is that in which ⑤ is replaced by ①, resulting in a ①–⑥–⑦–① progression:

In fact, this version of the bass occurs in bar 4 of the 1824 edition, albeit embellished with passing notes. This observation gives use the possibility to use this embellished bass in each segment of the Fonte-Romanesca. I give several options for bar 1a.

Note that in the penultimate bar of the last version, I have changed the whole note g in the bass into two half notes g–G, which is a typical gesture in a cadenza doppia.

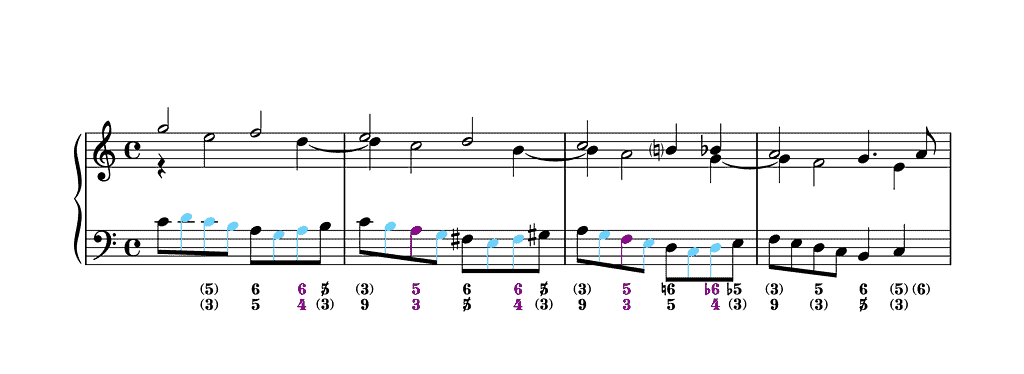

The following two versions embellish the bass of the Fonte-Romanesca in running eighth notes, the first completely in stepwise motion, the second with consonant leaps in the second half of each bar:

Note that

- in the first version, the original bass note on the fourth beat of bars 1 to 3 is shifted an eighth note to the right

- in bar 4 of the second version, beat 3 is also embellished with the leap of a third; while this embellishment could have been a d and would have continued the ornamental pattern, the choice of the ‘irregular’ G (resulting in a descending instead of an ascending third) gives a little more prominence to the ending of the Fonte-Romanesca.

Select Bibliography

Byros, Vasili. Mozart’s Vintage Corelli: The Microstory of a Fonte-Romanesca, in: Intégral 31 (2017), 63–89.

Demeyere, Ewald. Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue — Performance Practice Based on German Eighteenth-Century Theory (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2013).

Demeyere, Ewald. On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update, in: Eighteenth-Century Music 15/2 (2018), 207–229.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Kirnberger, Johann Philipp. Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik (Berlin and Königsberg, 1771/1774 (vol. 1). English translation in: The Art of Strict Musical Composition – Johann Philipp Kirnberger, ed. David Beach and Jurgen Thym (New Heaven and London: Yale University Press, 1982).

Schubert, Peter & Christoph Neidhöfer. Baroque Counterpoint (New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006).