In this essay, I will discuss a voice-leading pattern that is known today as the Leaping Romanesca. This schema, also called the Pachelbel Bass or Pachelbel sequence, occurs not only in many Baroque and galant compositions but also in many pedagogical assignments from the 17th and 18th century. In partimento methodology this schema was known as a bass that descends a fourth and rises a second. In this essay I will focus on the schema’s characteristics.

The Leaping Romanesca is usually defined today as a descending sequential pattern with 3 segments and 6 stages. Its characteristics: a bass alternating descending fourths and ascending seconds, a melody descending in stepwise motion starting on scale step 3, each stage set as a triad.

This essay will deal with the different settings of the Leaping Romanesca in two- and in three-part textures. I will show how those textures can be realized with only consonances but also with the inclusion of suspensions. Moreover, I will include Q&A moments, in which I will answer questions regarding voice leading you might have. And I will give tips on how to practise the material at hand.

To facilitate the reading of this essay, I use Robert Gjerdingen’s black-circled figures to indicate scale steps in an upper voice (e.g. ➍–➌) and white-circled figures to indicate scale steps in the bass (e.g. ⑦–①). And I add an accidental to a figure when the specific designation of a diatonic or a chromatically altered scale step is required, although this symbolized notation can differ from the actual one. The list below should suffice to make the system of indications clear. Regardless of the mode,

♭③ always refers to the scale step a minor third above ①

③ always refers to the scale step a major third above ①

♭⑥ always refers to the scale step a minor second above ⑤

⑥ always refers to the scale step a major second above ⑤

♭⑦ always refers to the scale step a major second below ①

⑦ always refers to the scale step a minor second below ①

Which Type of (Leaping) Romanesca?

This essay deals with the pattern as exemplified by bars 5–6a of the Canon in D major written by the German composer, organist and pedagogue Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706).

In his book Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento — A New Method Inspired by Old Masters from 2018, Job IJzerman calls this schema the Leaping Romanesca due to its bass that falls by fourths (and rises by seconds) in order to differentiate it from other variants of that pattern. (In his groundbreaking book Music in the Galant Style from 2007, Robert O. Gjerdingen speaks of a Romanesca with a leaping bass or a leaping variant/version of the Romanesca.) I agree with that. For students to fully absorb and apply different variants of a pattern, I have found it not only useful but also necessary to label those variants, albeit only descriptively. As such, I will use the term Leaping Romanesca instead of merely Romanesca throughout this essay.

This essay will not deal with the older harmonic sequence that formed the basis of many 16th- and 17th-century vocal and instrumental compositions and is also known as the Romanesca. For the latter, see the outstanding video by Elam Rotem on Early Music Sources.

While the ‘old’ Romanesca and the ‘Pachelbel Pattern’ do show similarities, their design and stylistic musical language are different. Obviously, it is the similarities that drove Gjerdingen to label the Pachelbel Pattern as Romanesca. Still, it is good to point out that in the context of galant music —music built on “a particular repertory of stock musical phrases employed in conventional sequences” (Gjerdingen, 2007, p. 6)— the term Romanesca is not a historical one.

For other galant types of Romanescas, I refer the reader to my other essays.

The Leaping Romanesca in Two Parts

In his third book of partimenti, the Neapolitan grandmaster of partimento Fedele Fenaroli (1730–1818) wrote a partimento in A major that starts as follows:

(For my critical edition of Fenaroli’s first three partimento books and regole, see https://essaysonmusic.com/resources/.)

When we omit the repeated notes, we obtain the skeleton version of this bass:

(Note that repeating notes is probably the simplest technique of ornamenting.)

A trained student from Fenaroli’s class —those students were exclusively young boys, male teenagers or young men— would immediately ‘recognize’ this bass. He would identify this fragment as a bass that descends a fourth and ascends a second. He would know that this pattern typically consists of three segments —the model and two transpositions. He would know that each transposition is a third lower than the previous segment. At the same time, he would come up with multiple, related settings.

Consonant Realizations

With The Upper Voice Starting on ❸

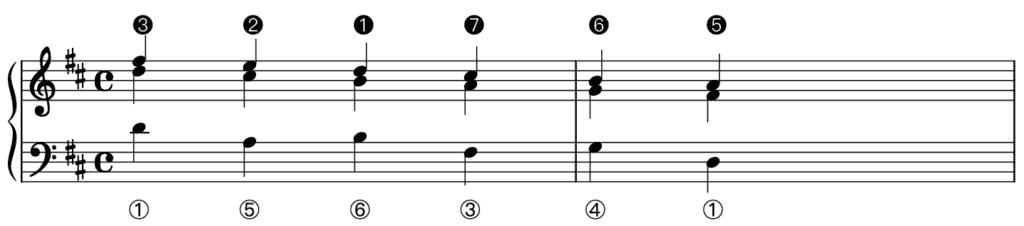

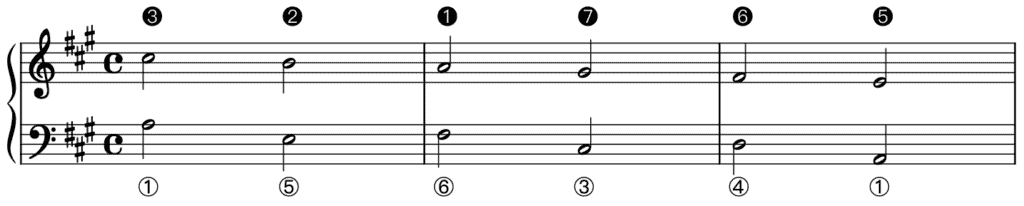

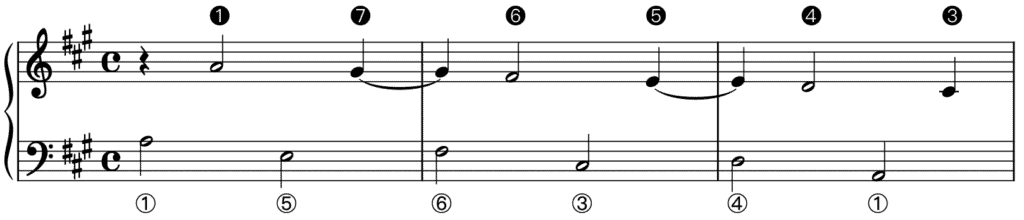

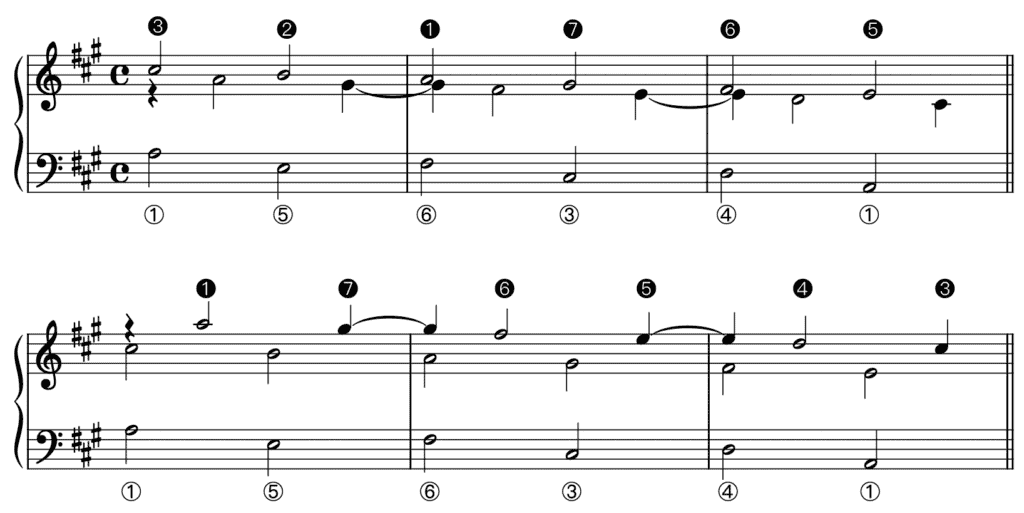

The most straightforward, first-choice two-part version of this schema is with an upper part that starts on ❸ and steps down until ❺. The following example shows this two-part realization:

In this version, the first stage of each segment contains a vertical third, the second a vertical fifth.

With The Upper Voice Starting on ❶

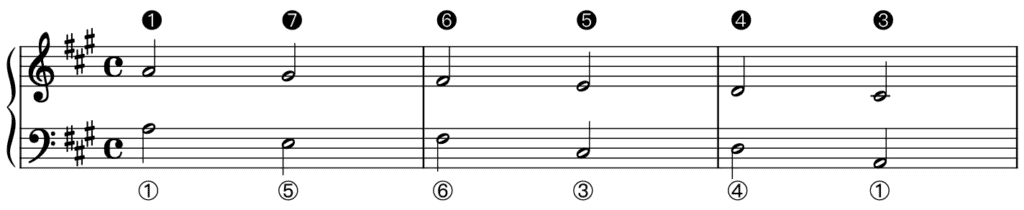

Alternately, the upper part can start on the octave, on ❶, after which it steps down until ❸. The next example shows this possibility:

In this version, the first stage of each segment contains a vertical octave, the second a vertical third.

Dissonant Realizations

Instead of rhythmically aligning the upper voice with the bass and using only vertical consonances, one can dislocate this voice one beat to the right, resulting in the appearance of an expressive chain of suspensions.

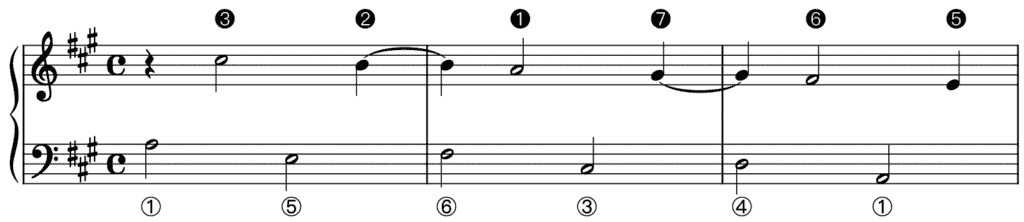

With a Suspension Chain Starting on ❸

When each note of the upper voice that starts on ❸ is shifted one quarter note to the right, a chain of suspensions emerges, alternating 6–5 and 4–3 suspensions:

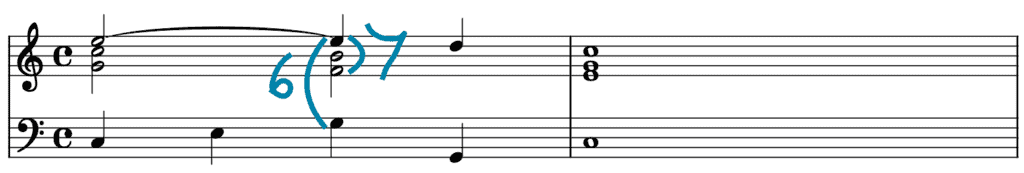

Q&A Moment

Isn’t a vertical sixth always a consonance? While that is indeed mostly the case, there are exceptions. For instance, a vertical sixth (in relation to the bass) acts as a dissonance when it temporarily replaces the fifth of a dominant seventh chord, producing a (dissonant) vertical second or seventh with the chord’s seventh:

With regard to the 6–5 suspensions in the example above, one might rather speak of pseudo dissonances since these notes do temporarily replace a chord factor yet aren’t genuine dissonances.

With a Suspension Chain Starting on ❶

When each note of the upper voice that starts on ❶ is shifted one quarter note to the right, a chain of suspensions emerges, alternating 4–3 and 9–8 suspensions:

The Leaping Romanesca in Three Parts

Consonant Realizations

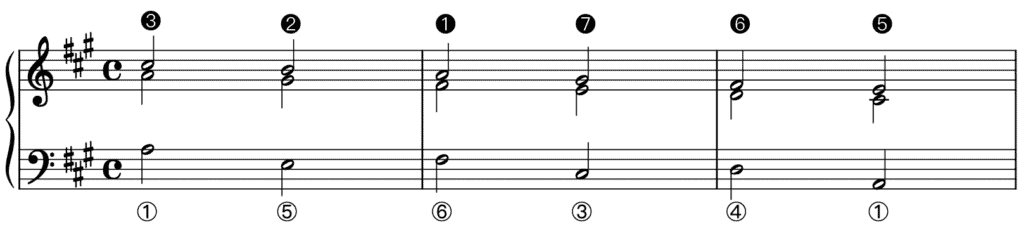

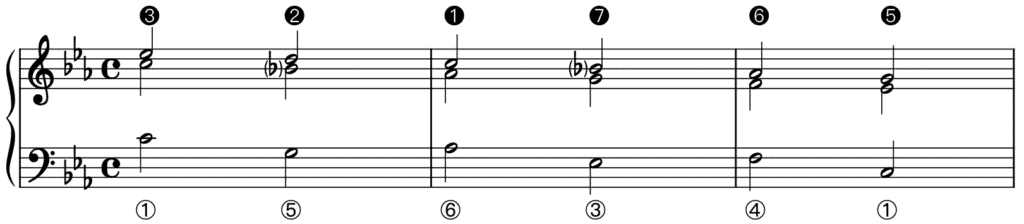

With The Upper Voice Starting on ❸

When we simultaneously play the upper voices of both two-part realizations, a satisfying three-part setting emerges in which each stage contains the vertical third in relation to the bass. In this version, each stage represents a triad, although only the triads during the even stages are complete, with the third in the middle voice and the fifth in the upper voice. As for the uneven stages, the bass note is doubled in the middle voice. The next example shows this rudimentary three-part version:

Q&A Moment

Can one omit the fifth from a triad? Yes. The presence of the fifth is not mandatory to define a triad. Under normal circumstances, one will perceive a bass note with its upper third as a triad on the bass note. (There are exceptions, which will be dealt with in another essay.)

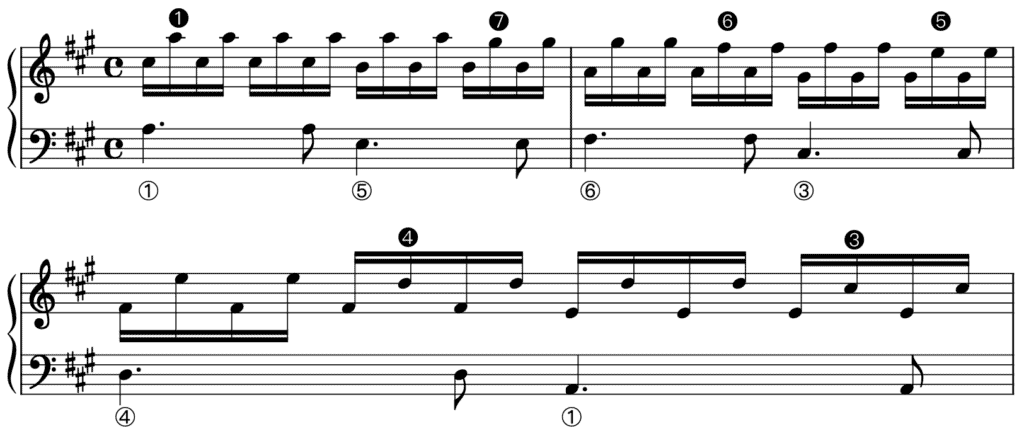

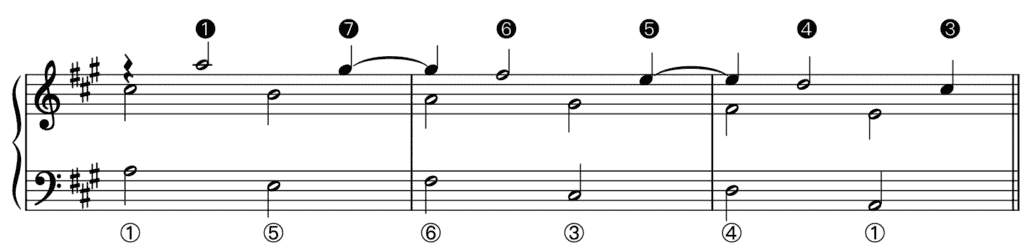

The realization above is one that probably sounds quite familiar. It is indeed identical, apart from being twice as slow and being set in a different key, to the first moment of three-part setting in Pachelbel’s Canon, the excerpt I referred to at the beginning of this essay. Here is it once more:

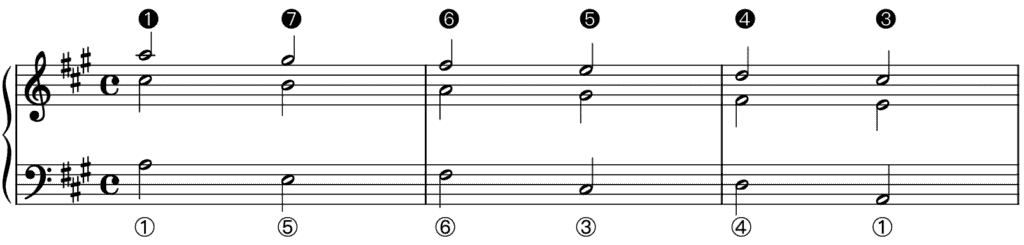

With The Upper Voice Starting on ❶

In the three-part setting we just saw, one can opt to swap both upper voices so that the middle voice becomes the upper voice and the upper voice becomes the middle voice. When several parts allow to be exchanged without causing voice-leading issues, one says that they are written in invertible counterpoint. Below you can see how this example looks when the upper voices are swapped, the vertical thirds they produce becoming vertical sixths:

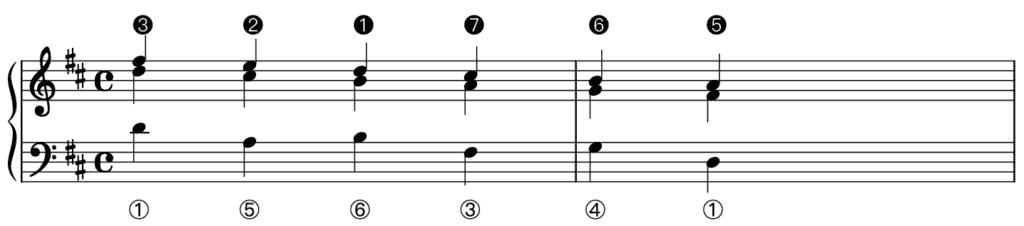

Dissonant Realizations

While the three-part versions I have discussed above include only triads and are perfectly usable, the Leaping Romanesca in three parts is more often set with suspensions, as the many examples from the past illustrate.

With One Suspension Chain Starting on ❶

The most typical setting of the Leaping Romanesca in three parts includes a chain of suspensions in the voice that starts on ❶. Consider the following examples:

In both cases, the voice that starts on ❶ does not align itself rhythmically with the two other voices but systematically moves one beat later than the others. As such, a chain of alternating 4–3 and 9–8 suspensions with the bass emerges. At the same time, this syncopated voice that starts on ❶ creates a chain of 2–3 suspensions (realization on the first system) or 7–6 suspensions (realization on the second system) with the other upper voice.

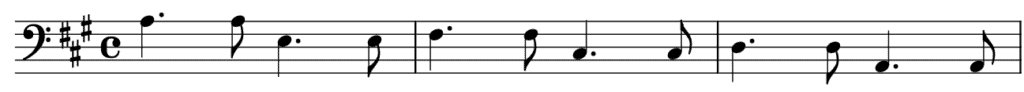

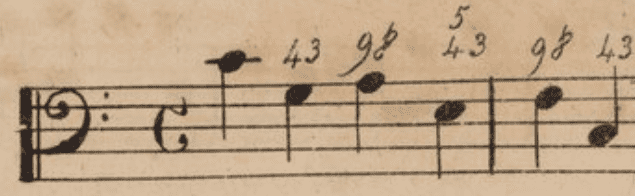

The next example illustrates how a composer or teacher could ask for this voice-leading including the suspension chain starting on ❶ by means of thorough-bass figures. This example shows the beginning of a partimento in C major from Pratica d’Accompagnamento Sopra Bassi Numerati E Contrappunti A Più Voci from 1824 by the Bolognese maestro padre Stanislao Mattei (1750–1825), imminent student of maestro padre Giovanni Battista Martini (1706–1784):

Q&A Moment

Why do we speak of 9–8 suspensions and not of 2–1 suspensions? Because one usually saw the ninth as a temporary substitute for the octave. Having a second go to a unison was not considered good voice leading. As a matter of fact, the second as a dissonance was also used, yet it was usually seen as a temporary substitute for the third. (Note my use of the adverb ‘usually’. Below, I will show an excerpt from a partimento by Giovanni Paisiello in which the composer does indicate twice “2–8” instead of “9–8”.) For more information see my essay on suspensions.

In the following video accompanying his latest book Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians from 2020, Gjerdingen too comments on the settings I have just discussed:

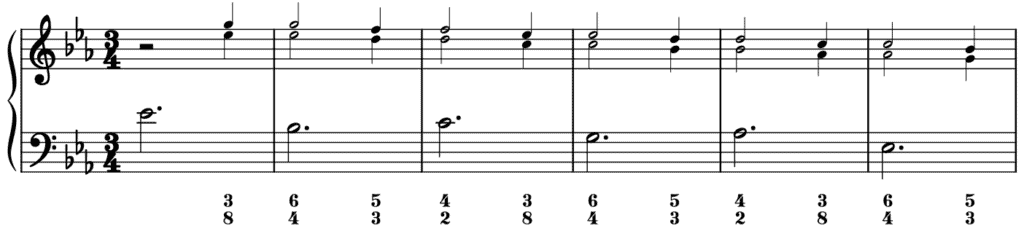

With Two Suspension Chains

The Leaping Romanesca in three parts can also be realized with two syncopated upper voices, with two simultaneous chains of suspensions. The next example shows such a setting from a partimento in C minor by another Neapolitan maestro Giovanni Paisiello (1740–1816); the Leaping Romanesca itself is presented here in E flat major. This partimento belongs to his Regole Per bene accompagnare il Partimento, a publication that saw the light in 1782 in Saint Petersburg when Paisiello worked at the court of Catherine the Great.

(Paisiello only wrote the bass staff with the figures; the realization in small notes is mine)

The presence of the figures makes clear that a suspension chain is starting not only on ❶ in the middle voice but also on ❸ in the top voice, resulting in another expressive realization with sighing quality. Note, incidentally, that in the bottom row of figures of bars 12 and 14, Paisiello did not write “9–8” but “2–8” (see the Q&A Moment above).

Q&A Moment

Why are the preparations and the dissonances in the example above not tied, as is the case in the previous examples? Observe first that the partimento above is written in a 3/4 time signature and that the preparation of each suspension is shorter than the dissonance: the preparation lasts a quarter note, the suspension a half note. Normally, the preparation of a suspension should be at least as long as the suspension itself. When that is the case, both notes can be tied. However, when the preparation is shorter than the suspension yet both notes are tied, this is considered a voice-leading flaw due to the syncopation that is rhythmically out of balance. To correct that, one can simply omit the tie. One might even object to still speak of a suspension in this case for the tying of the preparation and the dissonance is characteristic for the suspension. More coherent would be to speak of an appoggiatura, an ornament that shares the two stages of on-beat dissonance and off-beat resolution with those of the suspension, but appears without preparation.

Q&A Moment

Why do the figures below the staff in the example above not always appear in logical order, with the higher figure above the lower one? This is because these figures have a specific function that is less well known today. Figures can actually have two functions. First, and this is the best-known meaning today, a figure can illustrate which vertical sonority —which chord— one should play. Yet in partimento and counterpoint, figures are very (more) often used to indicate voice-leading in a stenographic way.

The Leaping Romanesca in Minor

Although less common, the Leaping Romanesca also occurs in minor, both with only consonances as with the inclusion of suspensions. In this case, it is customary to use ♭❼ instead of ❼ during stages 2 and 4 to allow it to step down to ♭❻.

A Leaping Romanesca Realized With One Suspension Chain Starting on ❶ and Bariolage

To finish this essay and to anticipate what I will be talking about in the next one, I want to show one example of how one can transform these rhythmically elementary versions into more accomplished and musically captivating realizations. In 1809, what must have been a student from Fenaroli’s circle penned a manuscript with the title Imitazione del Terzo Libro dèi Partimenti del Sig.r D: Fedele Fenaroli. This manuscript contains 24 so-called intavolature (fully written-out keyboard realizations) of the 49 partimenti from Fenaroli’s third book. The third intavolatura of the collection is a realization of partimento 27 from book 3 and sets the Leaping Romanesca with a suspension chain starting on ❶. Yet instead of rendering the three parts explicit, it shows a contrapuntally rudimentary yet much used technique of reducing the two upper voices of this setting into one voice by successively alternating a note of one voice with a note of the other voice, that is, the bariolage technique. For reference, I have reproduced the three-part version of the Leaping Romanesca set with a suspension chain starting on ❶, the chain appearing in the top voice, below the intavolatura.

I have made a modern edition of this important manuscript, which I have called The Parma Manuscript after the library where it is kept. It can be purchased via www.wessmans.com. At its current state of research, The Parma Manuscript is not only the earliest source with realizations of Fenaroli’s third book but also the only one from Fenaroli’s lifetime.

For more information on Fenaroli’s partimento and counterpoint curriculum, see my article On Fedele Fenaroli’s Pedagogy: An Update (2018) and the essay I wrote about it.

For more information on the bariolage technique, see my YouTube video:

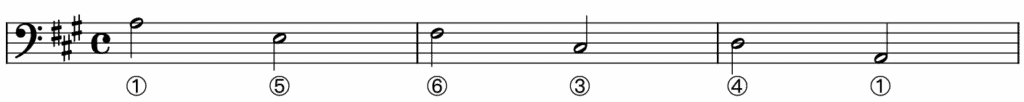

Tips for Practising

Before starting to practise the different realizations of the Leaping Romanesca in two and three parts, it is a good idea to play only its bass and get acquainted with it, also from a keyboard-technical point of view. To this end, I suggest playing it first in C major and then in all major keys up to at least four accidentals. It is important to become familiar with somewhat less common keys such as E major and A flat major. Once you are comfortable playing the Leaping Romanesca bass in a number of keys, you can start practising the various realizations. I would recommend starting with the two-part settings to maximize concentration on the sole upper voice. I suggest playing the two-part settings first in C major before passing on the keys with accidentals. After you have processed these settings, you can pass on to three-part settings, for which I suggest a similar approach. When you practise the three-part Leaping Romanesca realized with two chains of suspensions, I encourage you to practice the version with the suspension chain starting on ❶ in the top voice as well (not shown). It is also worthwhile to practise all the two- and three-part variants of the Leaping Romanesca that we have seen in major in a number of minor keys. Remember to use ♭❼ during stages 2 and 4.

Further Reading (Selection)

Primary Sources

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 1, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 2, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Partimenti, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. METODO PER BENE ACCOMPAGNARE LIBRO 3, Critical Comments, Critical edition, ed. Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. REGOLE MUSICALI PER I PRINCIPIANTI DI CEMBALO, A Comparative Edition (V1.0), compiled and edited by Ewald Demeyere (Ottignies, 2021).

Fenaroli, Fedele. The Parma Manuscript — Partimento Realizations of Fedele Fenaroli (1809), ed. Ewald Demeyere (Visby: Wessmans Musikförlag,2021).

Mattei, Stanisloa. Pratica d’Accompagnamento Sopra Bassi Numerati E Contrappunti A Più Voci (Bologna, 1824).

Paisiello, Giovanni. Regole Per bene accompagnare il Partimento (St. Petersburg, 1782).

Secondary Sources

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Child Composers in the Old Conservatories — How Orphans Became Elite Musicians (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

IJzerman, Job. Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Paraschivescu, Nicoleta. Die Partimenti Giovanni Paisiellos — Wege zu einem praxisbezogenen Verständnis (Basel: Schwabe Verlag, 2018).

Paraschivescu, Nicoleta (Translator: Chris Walton). The Partimenti of Giovanni Paisiellos — Pedagogy and Practice (New York: University of Rochester Press, 2022).

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. The Art of Partimento — History, Theory, and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).